Am Fam Physician. 2021;103(6):345-354

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Fractures of the radius and ulna are the most common fractures of the upper extremity, with distal fractures occurring more often than proximal fractures. A fall onto an outstretched hand is the most common mechanism of injury for fractures of the radius and ulna. Evaluation with radiography or ultrasonography usually can confirm the diagnosis. If initial imaging findings are negative and suspicion of fracture remains, splinting and repeat radiography in seven to 14 days should be performed. Incomplete compression fractures without cortical disruption, called buckle (torus) fractures, are common in children. Greenstick fractures, which have cortical disruption, are also common in children. Depending on the degree of angulation, buckle and greenstick fractures can be managed with immobilization. In adults, distal radius fractures are the most common forearm fractures and are typically caused by a fall onto an outstretched hand. A nondisplaced, or minimally displaced, distal radius fracture is initially treated with a sugar-tong splint, followed by a short-arm cast for a minimum of three weeks. It should be noted that these fractures may be complicated by a median nerve injury. Isolated midshaft ulna (nightstick) fractures are often caused by a direct blow to the forearm. These fractures are treated with immobilization or surgery, depending on the degree of displacement and angulation. Combined fractures involving both the ulna and radius generally require surgical correction. Radial head fractures may be difficult to visualize on initial imaging but should be suspected when there are limitations of elbow extension and supination following trauma. Treatment of radial head fractures depends on the specific characteristics of the fracture using the Mason classification.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Ultrasonography is an alternative to radiography for detection of forearm fractures, with a sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 95%.15 | A | Systematic review and diagnostic meta-analysis |

| Distal radius and ulnar buckle fractures in children are treated with short-arm (below-the-elbow) immobilization. Several options are available, including removable splints, wraps, or soft casts, without evidence to support one option over another.4 | B | Cochrane review with limited evidence |

| Recent evidence favors immobilizing nondisplaced distal radius fractures for three weeks rather than the traditional six weeks.7 | B | Systematic review of lower-quality cohort studies or with inconsistent findings |

| Nondisplaced radial head fractures should not be immobilized for more than two weeks because of the risk of stiffness.9,10 | C | Expert opinion |

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not order follow-up radiography for buckle (torus) fractures if they are no longer tender or painful. | American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Orthopaedics and the Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America |

The most common mechanism of injury for radius and ulna fractures is sudden axial loading onto the radius/ulna, often from a fall onto an outstretched hand with wrist extension.1,2 Although nondisplaced, or minimally displaced, fractures of the radius and ulna usually can be managed by family physicians, it is important to identify fractures that require referral to an orthopedist. The most common radius and ulna fractures, with a summary of their management and indications for referral, are shown in Table 1.2,4–11

| Fracture location/type | Initial treatment | Definitive treatment | Duration of immobilization | Indications for orthopedic referral |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distal radius buckle (torus)4 | Short-arm splint, soft cast, wrap | Short-arm splint, soft cast, wrap | 3 weeks | — |

| Greenstick/complete distal radius in children4,5 | Short-arm splint, soft cast | Short-arm splint, soft cast | 3 weeks | > 30 degrees of angulation or > 50% displacement |

| Distal radius in adults2,6,7 | Reduction followed by a lateral radiograph to verify distal radioulnar joint alignment; sugar-tong splint | Short-arm cast | 3 to 6 weeks | Concurrent dislocation, carpal fracture, ulnar styloid fracture, fracture instability/comminuted pattern, injury to radiocarpal or radioulnar ligaments, malunion |

| Combined radial and ulnar midshaft8 | Reduction, sugar-tong splint | Surgery | — | Distal radioulnar joint instability, associated intra-articular fractures, displacement, angulation, shortening, comminution, or rotation |

| Ulnar midshaft7 | Reduction, sugar-tong splint, posterior (ulnar gutter) splint | Conservative management if fracture is located in the middle or distal third of the diaphysis, displacement is < 50% of the bone diameter, and angulation is < 10 degrees All other: surgery | Immobilization in posterior splint for 10 days, then transition to a plaster sleeve or functional brace for 4 to 6 weeks | Any concurrent injuries of the radius, distal radioulnar joint, or elbow joint; comminution; displacement that does not meet the criteria for conservative management |

| Radial head9–11 | Posterior arm splint | Sling | 2 to 3 weeks | Mason types III and IV fractures; possibly type II fractures (Table 3) |

Most fractures of the radius or ulna seen by family physicians are distal radius, midshaft, or radial head fractures. Other fractures, such as proximal ulna fractures of the coronoid and olecranon, are less common and therefore not addressed in this article. Application of the various splints and casts discussed in this article was detailed previously in American Family Physician.12

Initial Evaluation

Patients with radius or ulna fractures often present with reduced range of motion in the joint adjacent to the fracture (i.e., wrist for distal fracture and elbow for proximal fracture).2,3,9 Among the examination findings that suggest a wrist fracture, painful dorsiflexion is the most sensitive (95.7%) and ecchymosis is the most specific (97.8%).13 Additional predictors of a distal fracture include wrist edema, deformity, and pain with forearm pronation.13 Proximal fractures often cause limited forearm pronation or supination and limited elbow flexion or extension.

Although initial studies of the elbow extension test (ability to fully extend the elbow) for ruling out elbow fractures were promising, more recent studies have not demonstrated high accuracy, even with concurrent focal tenderness.14

However, when evaluating patients for suspected proximal radius or ulna fractures, physical examination should include assessment for ulnar and radial collateral ligamentous injury using elbow varus and valgus stress testing14 (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bCqPTSgW3-c). In addition, patients with a suspected fracture should be evaluated for neurovascular compromise or skin puncture, which require urgent orthopedic consultation.2,3,9

Imaging

There are no well-validated clinical prediction rules to help guide when to use radiography for suspected radius and ulna fractures, as with other fractures (e.g., the Ottawa rules for ankle fractures). In most cases, radiography is performed when fractures of the radius or ulna are suspected based on presentation and physical examination findings.

A two-view (posteroanterior and lateral) radiograph is generally sufficient for forearm fractures; however, a third (oblique) view should be obtained for suspected wrist or elbow fractures to assess the extent, angulation, and displacement of the fracture.2,3,9 If initial radiograph findings are negative but fracture is still suspected (e.g., there is pain, tenderness, or weakness), splinting and follow-up imaging in seven to 14 days are warranted.

Ultrasonography is an alternative to radiography for detection of forearm fractures, with a sensitivity of 97% and specificity of 95%.15 Ultrasonography can be performed at the point of care, costs less than radiography, and avoids radiation exposure. However, availability, technician expertise, and lack of patient cooperation with the imaging procedure may limit its use. Radiography and ultrasonography can detect pathognomonic features of injury, such as the presence of a posterior and elevated anterior elbow fat pad (sail sign) associated with proximal radius and ulna fractures (Figure 1).

Computed tomography can be performed for further fracture characterization and grading (i.e., to verify comminution, displacement, or impaction), if not clear from a standard radiograph. Although not routinely recommended, some literature advocates performing computed tomography to exclude fracture after acute elbow trauma when the patient has limited elbow extension but negative radiograph findings.16 Magnetic resonance imaging is another follow-up imaging modality to consider when an alternate or concomitant diagnosis, such as bone contusion or ligamentous injury, is suspected.2,3,9

Common Radius and Ulna Fractures in Children

BUCKLE (TORUS) FRACTURES

Given the elasticity of children's bones, fracture patterns in children often differ from those in adults. Children commonly develop incomplete compression fractures, known as buckle or torus fractures, that demonstrate cortical bulging without cortical disruption. Buckle fractures of the distal radial (and often ulnar) metaphysis are common with injuries caused by a fall on an outstretched hand.3 On physical examination, a deformity may be visible or palpated if there is significant angulation, but the deformity is often minimal (Figure 2). Tenderness may be diffuse or focal. Buckle fractures can be diagnosed with radiography (Figure 3) or ultrasonography.

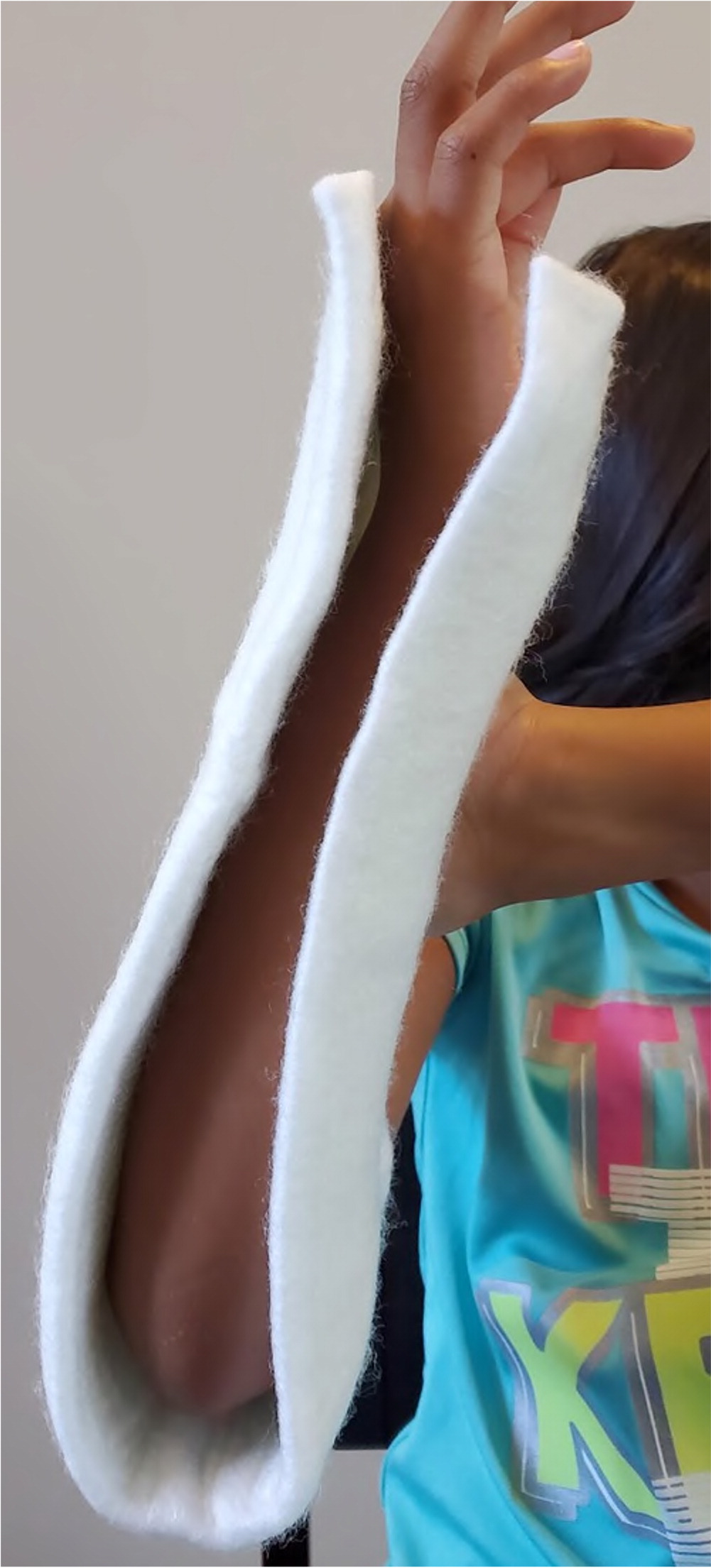

Distal radius and ulnar buckle fractures are treated with short-arm (below-the-elbow) immobilization. Several options are available, including removable splints (Figure 4), wraps, or soft casts. A Cochrane review found limited evidence to support one approach over another.4 Removable or nonrigid immobilization is often preferred for patient convenience and lower cost despite no significant benefit in pain reduction, functional recovery, or complication rate.

Regardless of which approach is used, immobilization may be discontinued after three weeks, followed by gradual return to usual activities as tolerated.3 Because of the low rate of complications, some recent studies have challenged the need for repeat radiography and follow-up clinic visits.17,18 However, many physicians prefer to evaluate patients for persistent signs or symptoms and to consider imaging before discontinuing care after a radius or ulna fracture.

GREENSTICK AND COMPLETE DISTAL RADIUS FRACTURES

A greenstick fracture is commonly confused with a buckle fracture. Greenstick fractures differ, however, in that they show cortical disruption on the tension side and cortical bulging on the compression side. Greenstick fractures are managed similarly to complete distal radius fractures rather than buckle fractures.5

Although accepted angulation varies with age, greenstick fractures and complete distal radius fractures in children can usually be managed with short-arm immobilization.5

In children younger than 10 years, up to 20 to 30 degrees of angulation in the sagittal alignment and 50% displacement are acceptable because of adequate bone remodeling. If these limits are exceeded, the patient should be referred to orthopedics.5 There are no guidelines for those 10 years and older.

Distal Radius Fractures in Adults

Distal radius fracture (Figure 5), the most common forearm fracture in adults, typically results from a fall on an outstretched hand.1,2 There is a bimodal age distribution in those most affected: young, healthy men who sustain high-energy injuries (e.g., from athletic collisions or motor vehicle crashes), and older women who have osteoporotic fractures from low-energy falls.1,2,19,20

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Adults with distal radius fractures often report focal wrist pain exacerbated by movement. Additionally, because the median nerve is commonly affected in distal radius fractures, carpal tunnel symptoms may be present in up to one-fourth of patients.19,21 Patients should be asked about hand dominance and activity levels to help determine how aggressive treatment should be.

Swelling or deformity is not always present on physical examination, but palpation of the carpal bones (scaphoid, ulnar styloid, lunate) may reveal tenderness, suggesting a fracture of those bones in addition to the distal radius.19,22 It is also important to check for median nerve injury, which would require referral to orthopedics for serial monitoring and consideration of reduction or carpal tunnel release if appropriate. Median nerve motor function can be assessed by having the patient touch the thumb to the tip of the fifth finger and hold it against resistance. Sensory function can be assessed by testing sensation on the palmar surface of the thumb through the radial half of the fourth finger.

IMAGING

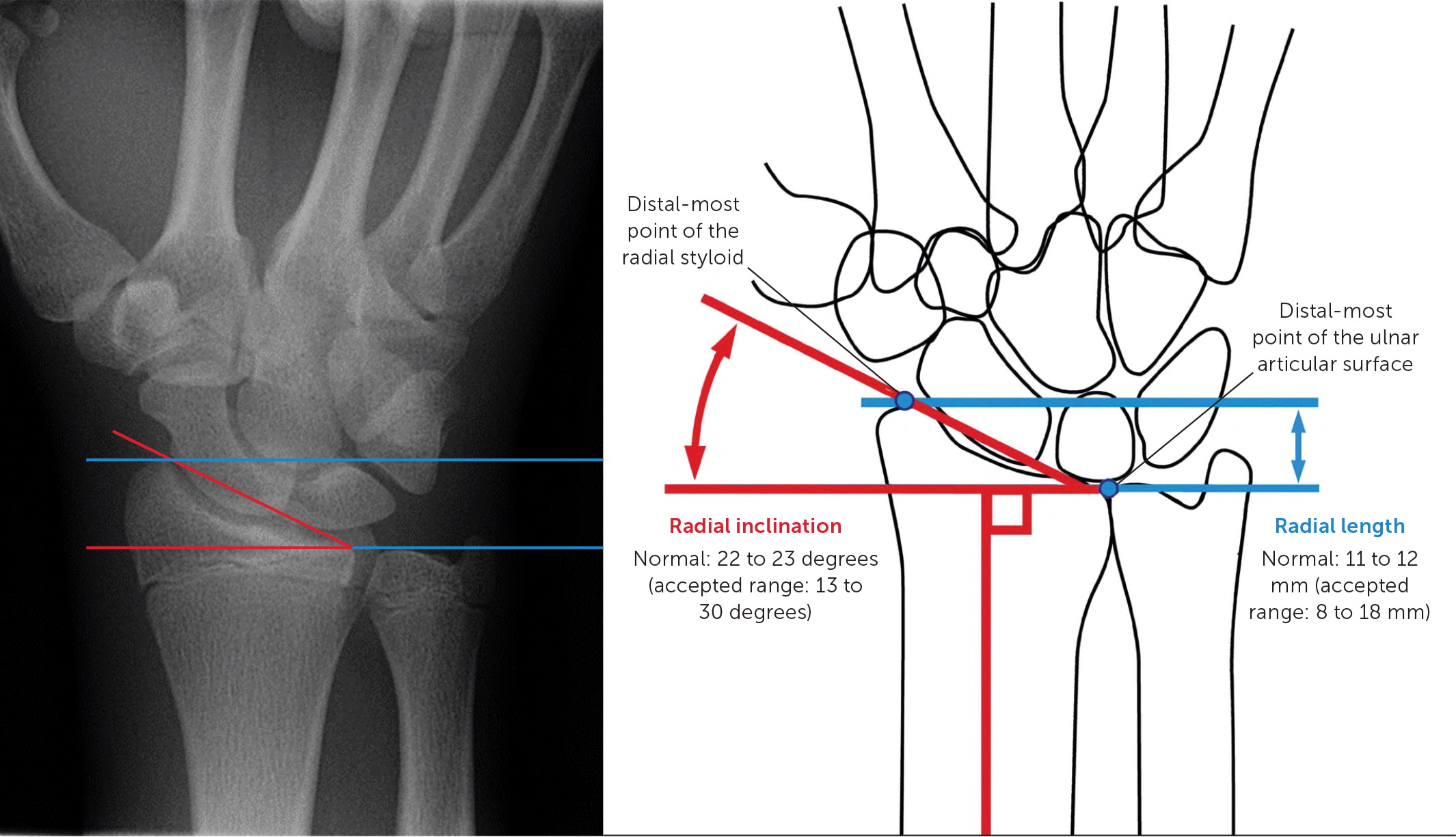

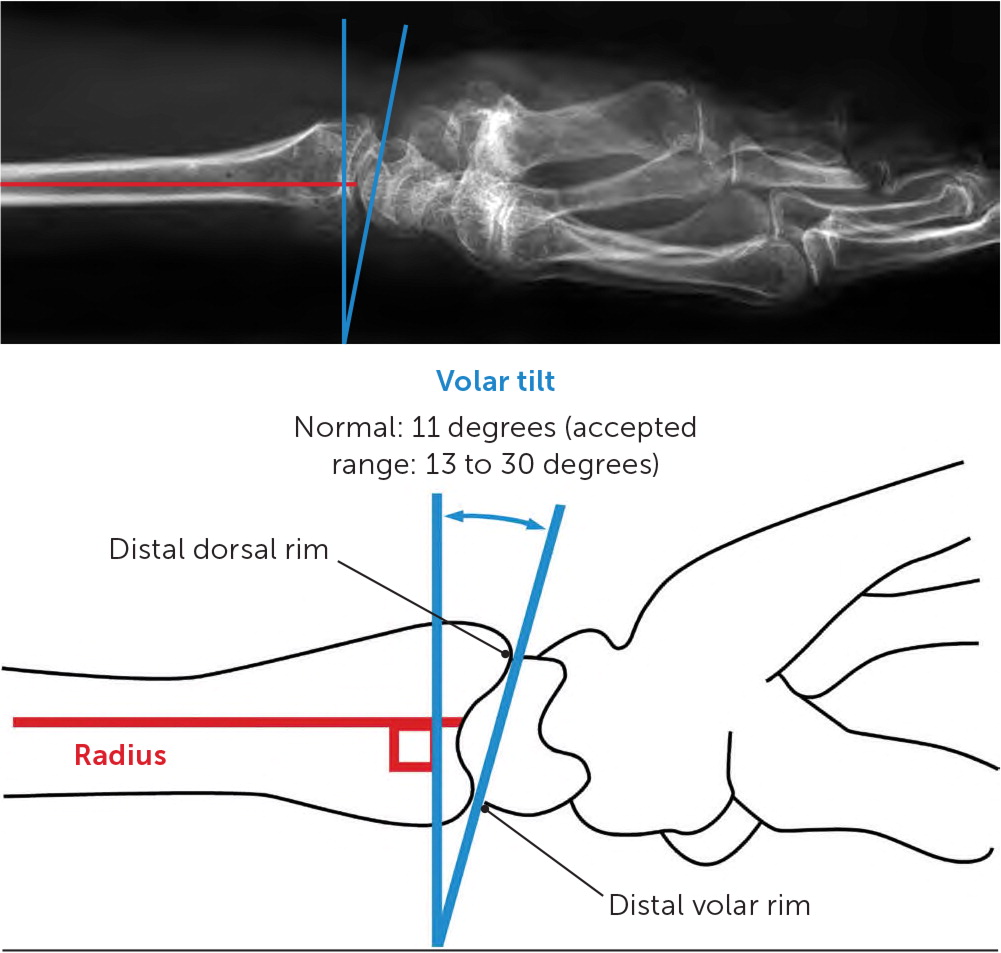

Diagnosis is confirmed with posteroanterior, lateral, and oblique radiographs.2,20 If radial inclination, radial length, and volar tilt fall outside of the values shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7,23 referral to an orthopedic surgeon within three to five days is recommended, unless immediate medical attention is indicated because of complications such as vascular compromise, compartment syndrome, or open fracture.20,24

TREATMENT

Patients with an incomplete fracture, a nondisplaced or minimally displaced complete fracture, or contraindication to surgery (e.g., medical comorbidities) can be managed nonsurgically with immobilization in the outpatient setting.2 Surgery is also not needed for displaced extra-articular fractures that can be reduced and maintained with no joint incongruity (parts of joints that should be adjacent to one another are no longer adjacent), no more than 2 mm of radial shortening, and less than 10 degrees of dorsal angulation of the distal articular surface.24

Once the fracture is stabilized, with adequate reduction verified on a radiograph and no neurovascular compromise, a sugar-tong splint (Figure 8) should be applied followed by a short-arm cast.6,20 Although the recommended duration of immobilization is variable, recent evidence favors immobilization of nondisplaced distal radius fractures for three weeks rather than the traditional six weeks.7,20,22,24

Complicated fractures that should be referred to an orthopedist include those with radiocarpal or distal radioulnar joint involvement, fracture displacement exceeding the limits noted earlier, a concomitant ulnar styloid or scaphoid fracture, suspected tendon injury, unacceptable postreduction alignment, or fracture with dislocation. The patient should be referred within three to five days to determine the need for closed reduction with percutaneous pinning vs. open reduction with internal fixation.2,20,22

Midshaft Radius and Ulna Fractures in Adults

| Fracture variation | Description | Mechanism of injury | Physical examination | Associated injuries |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monteggia | Ulna fracture with dislocation of the radial head at the radiocapitellar joint | Fall on an outstretched hand, with elbow extended and forearm hyperpronated | Assess radial nerve function, thumb extension | Radial head dislocation is often overlooked; palpate radial head in the antecubital fossa Radial nerve is commonly injured |

| Galeazzi | Distal to middle third of the radius, with dislocation of the radioulnar joint | Fall on an outstretched hand, with wrist extended and pronated | Assess for wrist deformity, tenderness at the distal radioulnar joint | Widening of the distal radioulnar joint space Ulnar styloid fracture Radius shortening Ulnar dislocation |

| Colles | Transverse fracture of the distal radius, with dorsal displacement of carpal/distal radius fragment | Fall onto an outstretched hand, with the forearm pronated | Assess for silver fork deformity Assess medial nerve function | — |

| Smith (reverse Colles) | Transverse fracture of the distal radius, with volar displacement of the carpal/distal radius fragment | Strike to dorsal wrist Cyclists sustain injury from falling over handlebars | Assess for volar displacement | — |

| Hutchinson (Chauffeur) | Fracture of the radial styloid process; intra-articular | Posterior-directed fall on an outstretched hand, with hand in ulnar deviation | Assess for scaphoid injury | Carpal injuries (scaphoid, lunate) |

| Barton | Distal radius fracture with associated dislocation/subluxation of the radiocarpal joint (Colles or Smith fracture with dislocation) | Requires significant force to occur: direct blow to the wrist or motorcycle accident | Rule out open fracture or compartment syndrome | — |

MIDSHAFT ULNA FRACTURE

An isolated ulna fracture can occur from a fall or from a direct blow to the forearm (nightstick fracture). It presents as localized tenderness and swelling of the forearm. Diagnosis is confirmed with anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the ulna. However, attention should be paid to the radial head to rule out a Monteggia fracture (ulnar fracture with dislocation of the radial head), which is sometimes overlooked.8,27

An isolated ulna fracture is managed nonsurgically with immobilization if it is located in the middle or distal third of the diaphysis, displacement is less than 50% of the bone diameter, and angulation is less than 10 degrees.20,27,28 Otherwise, the patient should be referred to an orthopedist for surgical correction.

Nonsurgical treatment typically involves application of a posterior (ulnar gutter) splint for 10 days, followed by a plaster sleeve or functional brace for four to six additional weeks.8,20 Although there is no evidence to support a formal recommendation, it is common to perform radiography weekly for the first two to three weeks to assure there is no subsequent displacement requiring orthopedic referral.1,8

COMBINED MIDSHAFT FRACTURES

Combined fractures involving both the radius and ulna are usually the result of a high-energy injury (e.g., from athletic collisions or motor vehicle crashes). Associated injuries to nerves, vessels, and soft tissue are common, thus requiring a careful examination of motor and sensory function of the nerves (radial, ulnar, and median).20,29 Similarly, attention to distal pulses and capillary refill is important because an injury to the vasculature can result in forearm compartment syndrome.20,29

Diagnosis of a combined fracture is confirmed with anteroposterior and lateral radiographs. Most combined fractures have displacement, angulation, shortening, comminution, or rotation, any of which require referral to an orthopedist.29 These fractures should be immobilized with a sugar-tong splint (Figure 8) and a sling. Combined fractures generally require surgical correction, and the patient should see an orthopedist within 48 hours.20

Radial Head Fractures in Children and Adults

Radial head fractures are the most common elbow fractures. Patients with this type of fracture typically have reduced extension and supination.16

EVALUATION

Radiographs sometimes appear normal in patients with radial head fractures because findings are subtle16 (Figure 9). Thus, when patients present with limitations of elbow extension and supination following trauma, a radial head fracture should still be suspected and follow-up radiographs obtained. If the diagnosis needs to be made at the time of presentation, computed tomography is indicated.16

Evaluation of elbow stability with varus and valgus stress testing is essential because more than one-half of radial head fractures, particularly displaced fractures, are associated with injuries to the lateral or medial collateral ligaments. In this case, orthopedic consultation may be appropriate.30,31

Findings of elbow joint effusion are also common on physical examination and radiography. Although effusion aspiration is often performed, there is no good evidence that it provides short- or long-term benefit.32

MANAGEMENT

| Type | Findings |

|---|---|

| I | Nondisplaced |

| II | Noncomminuted, > 2 mm displaced, and > 30% articular surface involvement |

| III | Entire head is comminuted |

| IV | Any fracture with elbow dislocation |

Patients with type I (nondisplaced) fractures may be transitioned from the splint to a sling as early as three or four days after the fracture, with continued use of the sling for two to three weeks.10 Type I fractures should not be immobilized for more than two weeks because of the risk of stiffness.9,10 Gradual increase in range of motion, strengthening, and protected use is encouraged.10 Despite the concern for postimmobilization stiffness and weakness, formal physical therapy has not demonstrated significant clinical benefit or cost-effectiveness.33 Return to full use may take three to four weeks in patients who have isolated fractures without ligamentous injury. Restrictions may need to be extended for another two to three weeks if there is ligamentous instability, lack of full range of motion, reduced strength, or incomplete healing shown on radiography.

No clear evidence supports surgical or nonsurgical treatment as the optional approach for type II fractures. Patients should be referred to physicians comfortable with managing these fractures, if necessary.11 Types III and IV fractures require referral to an orthopedist for surgical considerations.

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Black and Becker.23

Data Sources: We searched PubMed, Google Scholar, Essential Evidence Plus, the Cochrane database, and DynaMed Plus. We searched the following terms: forearm fracture epidemiology, radial buckle, torus, radial torus, radial head, ultrasound forearm fractures, elbow extension test, radius fracture, radial head fracture, olecranon fracture epidemiology, management, elbow instability, pediatric elbow injuries, coronoid fracture, forearm fracture, midshaft fracture, ulnar styloid, and ulna fracture. Search dates: December 23, 2019, to February 17, 2020.