Am Fam Physician. 2022;105(1):65-72

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Atherosclerotic vascular disease is a leading cause of death worldwide. Atherosclerotic stenosis of the internal carotid or intracranial arteries causes up to 15% of strokes. Peripheral artery disease affects up to one in five people in the United States who are 60 years and older and nearly one-half of those who are 85 years and older. Renal artery stenosis may affect up to 5% of people with isolated hypertension and up to 40% of people with other atherosclerotic diseases. All patients with atherosclerotic vascular disease should receive a comprehensive program of guideline-directed medical therapy, including structured physical activity and lifestyle modification, an antiplatelet agent, a statin, antihypertensive therapy, and smoking cessation counseling. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends one-time screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm with ultrasonography in men 65 to 75 years of age who have smoked at least 100 cigarettes, but screening is not recommended for carotid, peripheral, and renal disease. Surgical revascularization decreases adverse outcomes and mortality in selected patients with advanced vascular disease. Endovascular repair has become more common for patients younger than 70 years because of decreased short-term mortality. Carotid revascularization with carotid endarterectomy or carotid artery stenting is recommended for symptomatic patients with greater than 50% internal carotid artery stenosis. Carotid artery stenting is preferred in patients with multiple comorbidities, tracheostomy, or previous neck radiation or dissection. In patients older than 70 years, carotid endarterectomy is associated with a lower risk of periprocedural stroke or death than carotid artery stenting. Revascularization is a reasonable treatment option for patients with lifestyle-limiting claudication and an inadequate response to guideline-directed therapies. Revascularization is indicated for patients with critical limb ischemia and is emergently indicated for acute limb ischemia. Renal artery revascularization offers no proven clinical benefit when added to optimal medical therapy.

Atherosclerotic vascular disease is a leading cause of death worldwide. However, over the past few decades, the incidence of vascular disease and resultant mortality have declined in higher-income countries. The most significant risk factors for atherosclerotic vascular disease are hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and smoking.1 For abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA), smoking is the strongest predictor of prevalence, growth, and rupture, with a clear dose-response relationship.2 A family history of vascular disease increases risk, and the risk of developing AAA is doubled if a first-degree relative has an AAA. Standard medical treatment of atherosclerotic vascular disease, or guideline-directed medical therapy, includes structured physical activity and lifestyle modification, an antiplatelet agent, a statin, an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, and smoking cessation counseling with medical and psychological support (Table 1).3 Surgical revascularization decreases adverse outcomes and mortality in some patients with advanced vascular disease.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Men 65 to 75 years of age who have smoked more than 100 cigarettes in their lifetime should be offered a one-time screening for AAA with ultrasonography.2 | B | USPSTF grade B recommendation based on four large RCTs showing a 35% reduction in AAA-related mortality |

| Men 65 to 75 years of age who have never smoked can be offered one-time screening for AAA with ultrasonography; consider not screening patients with a reduced life expectancy or those who are not good candidates for surgical intervention.2 | B | USPSTF grade C recommendation based on four large RCTs, with only one reporting outcomes by smoking status in the screened group |

| AAA screening should not be offered to women who have never smoked and do not have a family history of AAA.2 | B | USPSTF grade D recommendation based on one trial demonstrating no benefit from screening in women who have never smoked and do not have a family history of AAA; evidence of benefit in women who have ever smoked or who have a family history of AAA is too limited to make a recommendation |

| Patients with an AAA ≥ 5.5 cm (2.2 in) in diameter should be referred for surgical repair.2,8 | B | AAA repair for aneurysms ≥ 5.5 cm (2.2 in) decreases mortality, but there is no evidence of benefit for AAA repair of aneurysms < 5.5 cm; most available data are from RCTs conducted in men |

| Do not screen adults who are asymptomatic for carotid artery stenosis.15 | B | USPSTF D recommendation based on multiple trials demonstrating the harms of treatment of asymptomatic carotid stenosis outweigh the benefits |

| Symptomatic patients with > 50% internal carotid artery stenosis should be referred for consideration of carotid revascularization.13 | A | Moderate- or high-quality evidence from three nonblinded trials demonstrating significant reduction in five-year risk of stroke or operative death with carotid revascularization Carotid artery revascularization is most beneficial for patients with ≥70% stenosis |

| Patients with signs of critical and acute limb ischemia should be referred for revascularization to preserve limb integrity with acute ischemia being an emergent indication.3 | C | American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology clinical practice guideline |

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not screen for carotid artery stenosis in adult patients who are asymptomatic. | American Academy of Family Physicians |

| Do not screen for renal artery stenosis in patients without resistant hypertension and with normal renal function, even if known atherosclerosis is present. | Society for Vascular Medicine |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker |

| Lifestyle modification, preferably including a structured exercise program |

| Low-dose aspirin |

| Smoking cessation with medical and psychological support |

| Statin, at least moderate intensity |

Abdominal Aortic Disease

AAA affects 1% of women and nearly 10% of men between 65 and 80 years of age.4 AAA is rare in people younger than 50 years.4 The prevalence of AAA in European countries has declined, likely due to decreased smoking. Because recommended screening is rarely performed, the current prevalence of AAA in the United States is uncertain.2

Screening for AAA with ultrasonography has a sensitivity of 94% or greater and a specificity of 98% or greater.2 The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends one-time screening for AAA with ultrasonography in men 65 to 75 years of age who have smoked 100 or more cigarettes in their lifetime.2 One-time screening for AAA with ultrasonography may be considered in men 65 to 75 years of age who have never smoked, but screening is not recommended in women who have never smoked or do not have a family history of AAA.The evidence is insufficient to recommend for or against screening women who have ever smoked or have a family history of AAA. Consider not screening patients with a lower life expectancy or those who are not good candidates for surgical intervention. The USPSTF recommends using sex and not gender identity for screening decisions.2 The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) endorses the USPSTF recommendations.5

For men 65 to 79 years of age, screening for AAA prevents aneurysm rupture (number needed to screen = 294) and mortality from AAA (number needed to screen = 917). These benefits have not been demonstrated in women.6

Rupture of AAA is a surgical emergency with high mortality. For patients who survive long enough to reach a hospital, 80% die before discharge.4 The annual risk of rupture is 1% for smaller aneurysms but increases to 11% when the diameter reaches 5 cm (2 in).7 Elective repair of an AAA less than 5.5 cm (2.2 in) has not been shown to decrease mortality.8

Surgical repair is standard practice for patients with an AAA of 5.5 cm (2.2 in) or larger in diameter or any AAA larger than 4.0 cm (1.6 in) that has increased by 1.0 cm (0.4 in) or more over one year.2 Because most trials were conducted in men, the threshold for surgical intervention in women is not well established.2

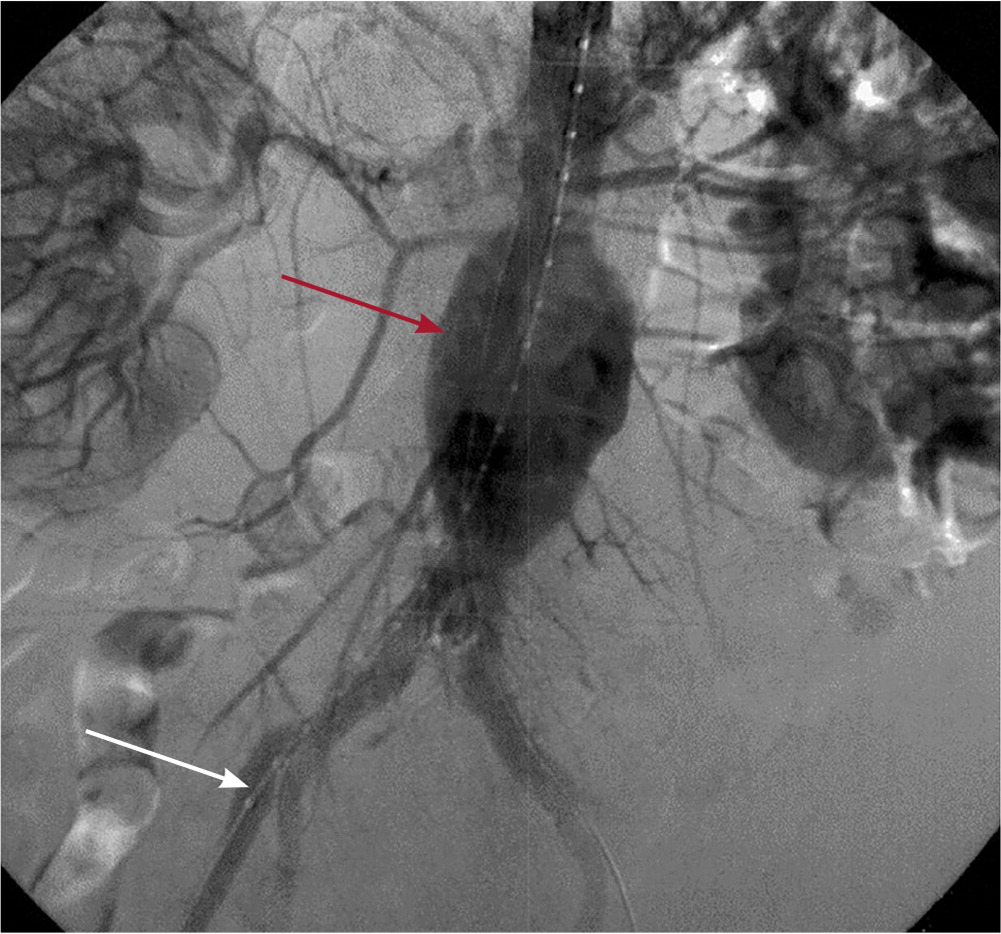

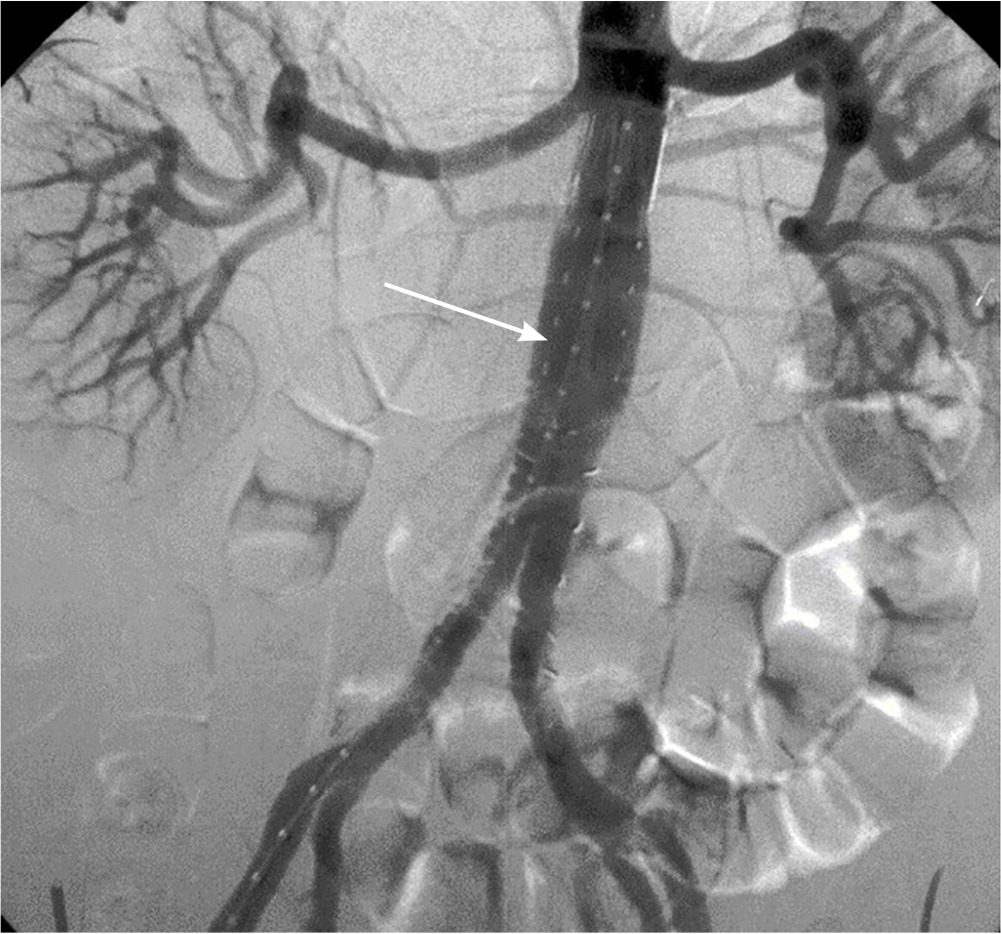

Open surgical repair has been the traditional approach when a repair is indicated; however, endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) has become more common than open repair over the past two decades.7 During the EVAR procedure, bilateral femoral artery catheters are used to place an endograft across the aneurysmal portion to act as an artificial lumen and protect the aneurysm from vascular pressure (Figure 1 and Figure 2).

In the United States, EVAR is currently used for 80% of intact AAA repairs and 52% of ruptured AAA repairs.7 EVAR has about one-third of the 30-day mortality rate vs. open repair.9 EVAR has lower mortality rates compared with open repair until approximately four years, when survival after both procedures is equivalent.10 When outcomes are separated by age, overall survival is higher with EVAR for patients younger than 70 years, and the two procedures are equivalent in people 70 years and older.11 Repeat interventions to address complications such as a leak or device migration are more common with EVAR.9

Carotid Artery Disease

Stroke is the second leading cause of death worldwide and the fourth leading cause of death in the United States.12 Although mortality after a first stroke can be as high as 35%, subsequent strokes are associated with a mortality of nearly 70%.13 Repeat strokes commonly occur within one year. Up to 15% of strokes are caused by atherosclerotic stenosis of the internal carotid or intracranial arteries.14

In patients without symptoms, screening for carotid artery stenosis does not improve outcomes and is not recommended by the USPSTF or the AAFP.15,16 The low prevalence of carotid artery stenosis in the population leads to a high rate of false-positive results. No reliable method exists to estimate stroke risk for patients who are asymptomatic with carotid artery stenosis.15

Carotid auscultation is also not useful to diagnose or rule out carotid artery stenosis. In addition to stenosis, bruits are commonly caused by transmitted cardiac murmurs, external carotid stenosis, venous hum, and tortuous arteries.

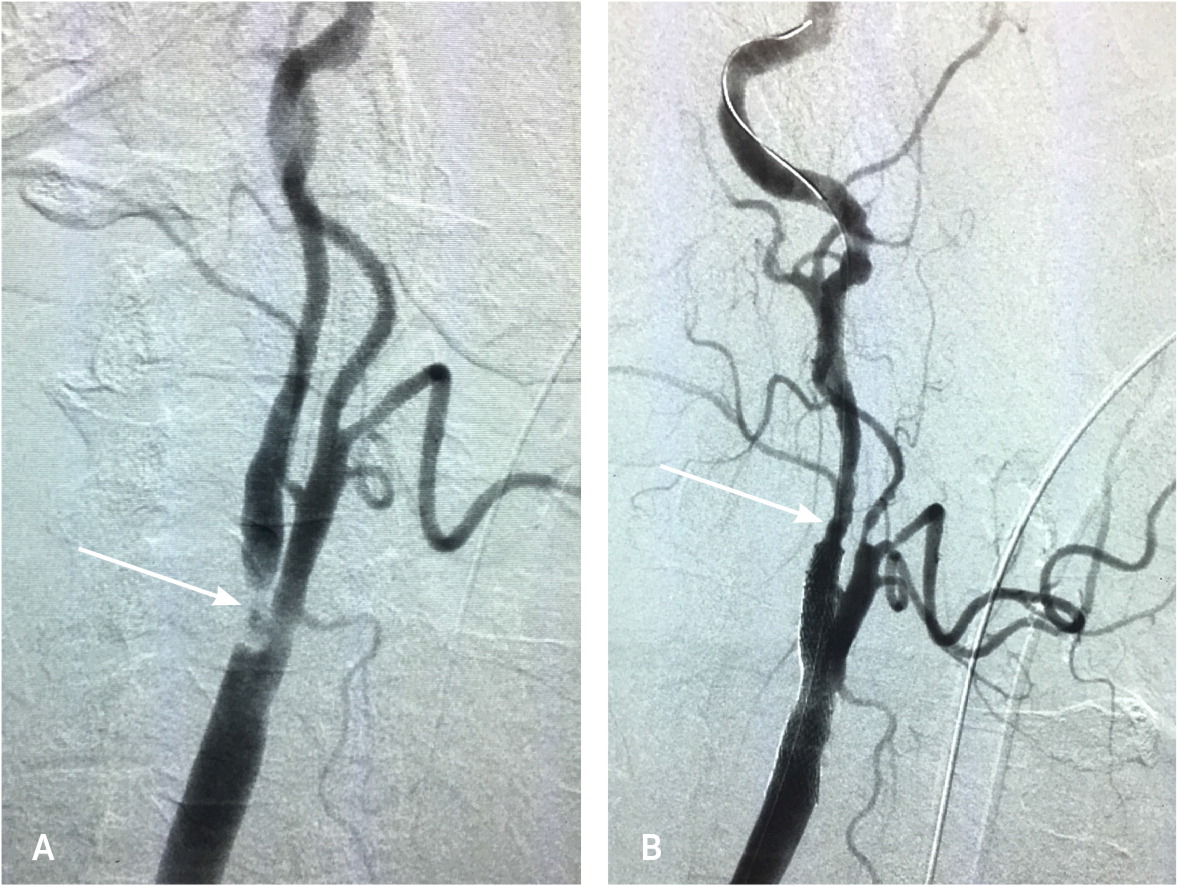

Imaging can be helpful for symptoms that suggest carotid disease. Carotid stenosis is considered symptomatic if patients have a history of transient ischemic attack, amaurosis fugax, or stroke in the distribution of the narrowed artery.17 Duplex ultrasonography is the most commonly used study to evaluate for stenosis. The degree of stenosis is estimated by measuring blood flow velocity at multiple points across the artery. The severity of the obstruction correlates with carotid flow velocity: the narrower the lumen of the vessel, the higher the flow rate through the stenotic segment. Tortuosity and heavy calcification of the artery may affect flow velocity measurements and estimation of stenosis. Computed tomographic angiography and magnetic resonance angiography can add to ultrasonography results by showing plaque morphology, intracranial collateralization, and brain perfusion that can affect stroke risk.

Without surgical intervention, strokes will affect approximately 1% of patients with carotid artery stenosis of 70% or more who receive guideline-directed medical therapy.17 Because older studies reported annual stroke rates of approximately 2% without surgical intervention, the current benefit from surgery is less clear. An ongoing trial (CREST-2) comparing carotid endarterectomy, carotid artery stenting, and medical management alone should clarify the relative benefit of intervention.18,19

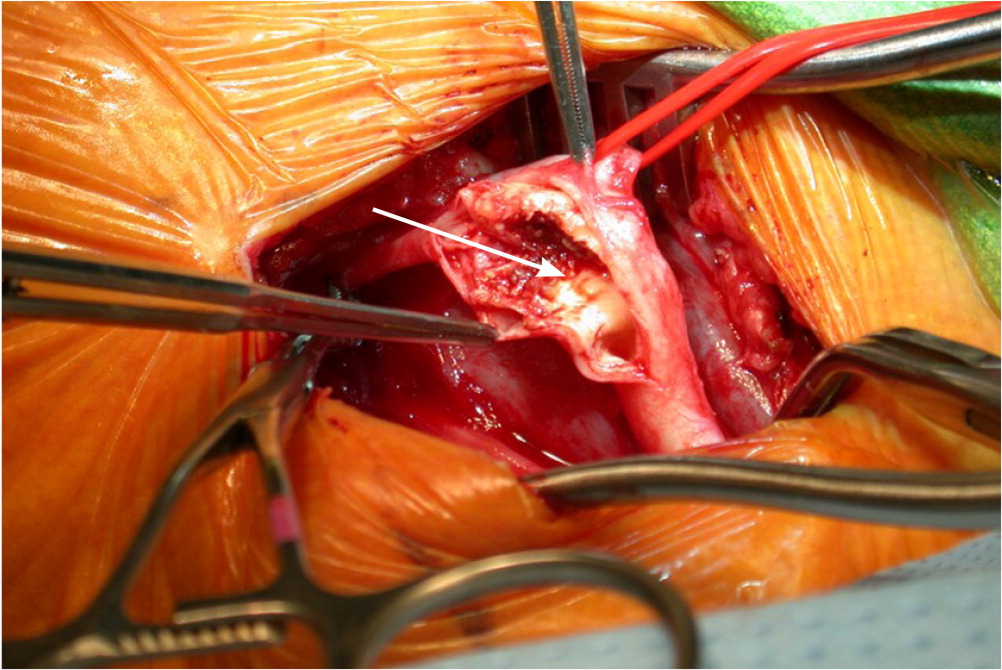

The most recent guidelines for stroke prevention are from 2021. Carotid endarterectomy is recommended for patients with transient ischemic attack or ischemic stroke within the past six months and ipsilateral severe (i.e., 70% to 99%) carotid artery stenosis when the estimated perioperative morbidity and mortality risk is less than 6%20 (Figure 3). The National Surgical Quality Improvement Program surgical risk calculator (https://riskcalculator.facs.org/RiskCalculator) is a validated tool to estimate the risk of postoperative complications.19 Carotid endarterectomy can be considered for symptomatic carotid stenosis of greater than 70% by noninvasive imaging or 50% by angiography unless medical comorbidities or anatomic conditions increase surgical risk.20 Conditions that increase surgical risk include multiple comorbidities, tracheostomy, previous neck radiation or dissection, or restenosis after previous carotid endarterectomy 20,21 (Figure 4).

Stenting has more short-term complications than surgery in older patients. Over the first three months after an intervention, carotid artery stenting has a number needed to harm of 32 for stroke or death compared with carotid endarterectomy. This increased risk is attributed to the risks of stenting an unstable plaque.21,22 In patients 70 years and younger, these three-month event rates are nearly identical with stenting and endarterectomy. After three months, carotid artery stenting and carotid endarterectomy are equivalent.23

Carotid endarterectomy within two weeks of symptom onset in patients with carotid artery stenosis greater than 50% reduces the risk of stroke with a number needed to treat of 5 over five years.13 After 12 weeks from the onset of symptoms or a stroke, the number needed to treat to prevent a stroke increases to 125. Carotid endarterectomy has a high short-term complication rate, with 7% of patients experiencing stroke or death within 30 days; 15% of patients experience stroke or death within five years of the procedure.13 Stroke within 30 days of carotid endarterectomy dramatically increases mortality.24

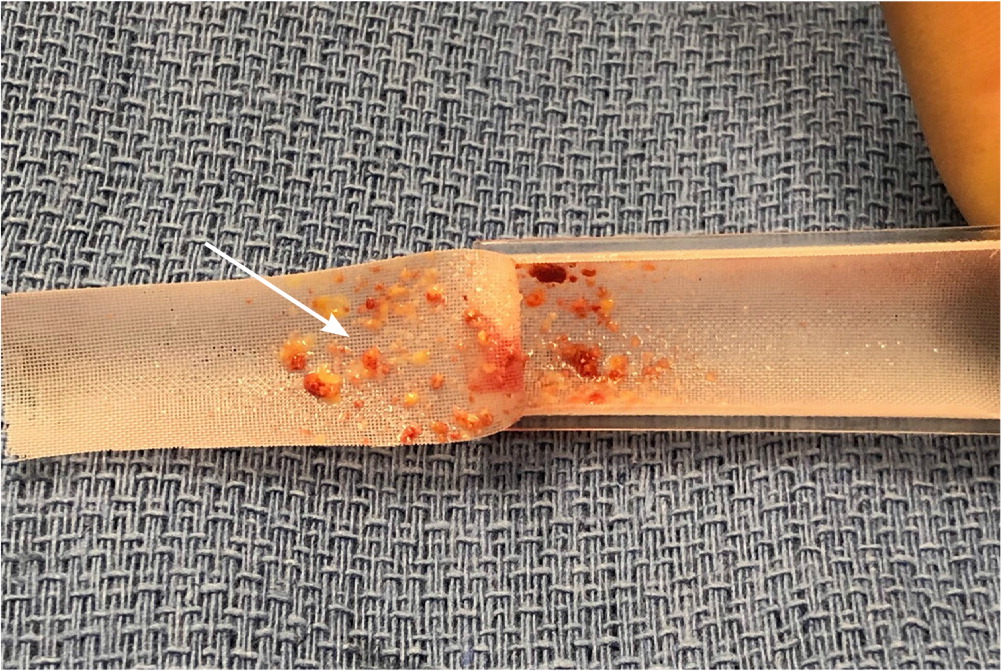

Transcarotid artery revascularization is a newer surgical approach for carotid stenosis. In transcarotid artery revascularization, carotid artery stents are placed by incising the affected artery. During the procedure, the carotid artery is clamped proximal to the stenosis, and the distal carotid flow is reversed using an extracorporeal circuit to the femoral vein. This protects the cerebral arteries while the backflow removes atherosclerotic debris released from the surgery (Figure 5). In a single-arm study of transcarotid artery revascularization in patients at high risk of complications from endarterectomy, only 2.3% of patients experienced stroke or death within 30 days of surgery.25

Peripheral Artery Disease

The ankle-brachial index (ABI) is an inexpensive and reproducible initial test for patients with PAD symptoms (e.g., intermittent claudication, diminished peripheral pulses). The ABI is calculated by dividing the systolic pressure of an artery of the ankle by systolic pressure in the arm and is typically greater than 0.90. ABI has a sensitivity of at least 94% for detecting angiographically significant stenoses.28 ABI is less sensitive in patients with small vessel disease from atherosclerosis associated with hypertension, diabetes, or chronic kidney disease. The USPSTF and AAFP conclude that current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of screening for PAD with ABI in adults who are asymptomatic.29,30

Two manifestations of PAD have the strongest indications for revascularization. Critical limb ischemia (CLI) is manifested by ischemic rest pain for more than two weeks, ischemic wounds or tissue loss, or gangrene in one or both legs (Figure 6). Up to 21% of patients with intermittent claudication eventually progress to CLI. Patients with CLI have an annual mortality rate approaching 25%, primarily from cardiovascular causes.31 Revascularization is indicated in CLI for limb preservation but has minimal effect on mortality.

Acute limb ischemia is a surgical emergency due to abrupt interruption of arterial blood flow to an extremity. Acute limb ischemia may present with a cold, painful, or pale extremity, diminished or absent pulses, motor weakness, or sensory impairment. Urgent revascularization is required in acute limb ischemia to preserve limb integrity.

CLI and acute limb ischemia are the strongest indications for revascularization. Revascularization is a treatment option for patients with lifestyle-limiting claudication who do not respond to other guideline-directed therapies. Revascularization is not beneficial in patients with incidentally discovered PAD.3

Surgical interventions, including bypass grafting, endarterectomy, and angioplasty with or without stenting, have similar outcomes based on limited evidence. Endovascular revascularization (angioplasty) is associated with fewer complications than bypass grafting; therefore, it may be more appropriate for patients with significant comorbidity and associated increased surgical risk.32

Renal Artery Disease

Atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis (RAS) commonly coexists with atherosclerotic conditions such as coronary artery disease and PAD. Up to 5% of patients with isolated hypertension have RAS, increasing to 40% in patients with clinically evident atherosclerotic diseases. By disrupting intrarenal hemodynamics, RAS can accelerate the progression of hypertension and chronic kidney disease.33

RAS is difficult to accurately diagnose by noninvasive methods. Vascular duplex ultrasonography is an accurate screening tool but does not often correlate well with computed tomography and magnetic resonance angiography, which may overestimate RAS. Angiography, the diagnostic standard, is also subject to interobserver variability and does not always correlate with ultrasonography, computed tomography, or magnetic resonance angiography.33

Renal artery stenting does not improve outcomes compared with optimal medical therapy 34 (Table 13). Despite the lack of prospective evidence, some vascular surgeons recommend considering renal artery revascularization in patients with significant clinical effects from stenosis. Patients with unilateral stenosis, normal renal function, and abrupt onset or worsening of severe hypertension despite more than three antihypertensive medications are typically considered for intervention. Other possible indications for renal artery stenting include patients with bilateral stenosis and rapidly declining renal function and younger patients with fibromuscular dysplasia affecting the renal artery.

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Lee, et al.35

Data Sources: A search of PubMed was completed using the key words carotid artery disease, carotid artery stenosis, abdominal aortic aneurysm, peripheral artery disease, and renal artery stenosis. The search included systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, and review articles. Also searched were Essential Evidence Plus, Cochrane Library, and U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. References within these resources were also searched. Search dates: August 2020, March 2021, and August 14, 2021.