Am Fam Physician. 2022;105(1):55-64

Patient information: See related handout on pruritus, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Pruritus is the sensation of itching; it can be caused by dermatologic and systemic conditions. An exposure history may reveal symptom triggers. A thorough skin examination, including visualization of the finger webs, anogenital region, nails, and scalp, is essential. Primary skin lesions indicate diseased skin, and secondary lesions are reactive and result from skin manipulation, such as scratching. An initial evaluation for systemic causes may include a complete blood count with differential, creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels, liver function tests, iron studies, fasting glucose or A1C level, and a thyroid-stimulating hormone test. Additional testing, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate, HIV screening, hepatitis serologies, and chest radiography, may also be appropriate based on the history and physical examination. In the absence of primary skin lesions, physicians should consider evaluation for malignancy in older patients with chronic generalized pruritus. General management includes trigger avoidance, liberal emollient use, limiting water exposure, and administration of oral antihistamines and topical corticosteroids. If the evaluation for multiple etiologies of pruritus is ambiguous, clinicians may consider psychogenic etiologies and consultation with a specialist.

Pruritus is the sensation of itching. Although large-scale epidemiologic data on prevalence are limited, pruritus is a common symptom encountered in primary care.1,2 The etiology of pruritus is complex and can include histamine, serotonin, and neuropeptide release, and neuronal itch signal transmission.1 Risk factors include older age, known or new dermatologic disease, and systemic conditions, such as renal and hepatic disease.1 When inadequately treated, pruritus can adversely affect a patient's quality of life by altering mood, stress levels, and sleep.3

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of pruritus is broad and includes acute and chronic (i.e., at least six weeks of symptoms) presentations.1,2 Primary and secondary skin lesions suggest dermatologic etiologies of pruritus (Table 14). When distinct exposures result in symptoms, the underlying etiology is often discovered. However, the absence of obvious triggers or examination findings coupled with chronic symptoms makes identifying the underlying etiology of pruritus more challenging.

| Etiology | Features |

|---|---|

| Allergic or irritant contact dermatitis | Bullae, vesicles, erythema, and edema localized to area in contact with exposure Reaction within days of exposure |

| Atopic dermatitis | Erythematous papules, patches, or plaques; pruritic area where rash appears when scratched in patients with atopic conditions (e.g., allergic rhinitis, asthma) Involvement of crease areas (axillae, wrists, ankles, popliteal and antecubital fossae) Chronic, worsens with itch-scratch cycle |

| Bullous pemphigoid | Initially pruritic urticarial lesions, often in intertriginous areas Formation of tense blisters |

| Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (mycosis fungoides) | Oval eczematous patch on skin with no sun exposure (e.g., buttocks) Possible presentation of new eczematous dermatitis in older adults Possible presentation of erythroderma |

| Dermatitis herpetiformis | Rare vesicular dermatitis affecting the lumbosacral spine, elbows, or knees |

| Dermatophyte infection | Can occur on several sites, including the feet, trunk, groin, scalp, and nails Localized pruritus and rash characterized by peripheral scaling and central clearing Patchy alopecia on scalp Dystrophic or discolored nails |

| Folliculitis | Pruritus out of proportion to appearance of dermatitis Papules and pustules at follicular sites on chest, back, or thigh |

| Lichen planus | Lesions often located on the flexor wrists Characterized by the six P's (pruritus, polygonal, planar, purple, papules, plaques) |

| Lichen simplex chronicus | Localized, intense pruritus Initial erythematous, well-defined plaques with excoriations lead to thickened, lichenified, violaceous patches if scratching continues |

| Pediculosis (lice infestation) | Adult organisms and nits on hair shafts Occiput in school-aged children; genitalia in adults (sexually transmitted) |

| Psoriasis | Plaques on extensor extremities, low back, palms, soles, and scalp |

| Scabies | Burrows, vesicles, and papules in finger web spaces and axillae and on wrists, ankles, genitals, and extensor surfaces Pruritus worse at night Can persist after mite eradication |

| Sunburn | Possible photosensitizing cause (e.g., with use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or cosmetics) |

| Urticaria (hives) | Intensely pruritic, well-circumscribed, erythematous, and elevated wheals Lesions are transient, may coalesce, and wax and wane over several hours |

| Xerosis | Intense pruritus, often during winter months in northern climates Involvement of back, flank, abdomen, waist, and lower extremities More common in older people |

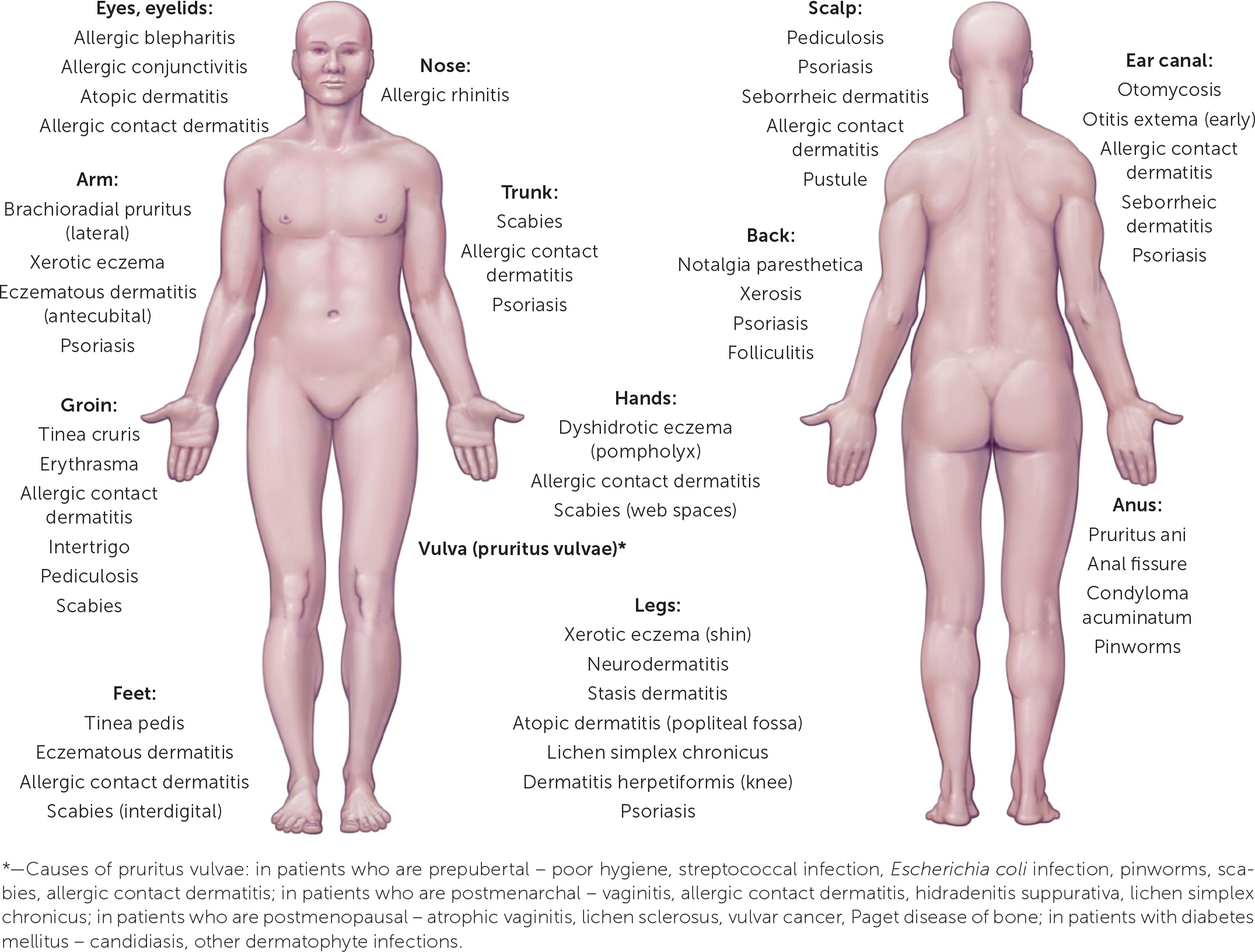

The International Forum for the Study of Itch has proposed a formal classification system for chronic pruritus with three different clinical classes: pruritus on diseased skin (Group I), pruritus on nondiseased skin (Group II), and chronic reactive lesions acquired from skin manipulation, such as rubbing, picking, or scratching (Group III).5 Group I presentations suggest a dermatologic etiology. Group II presentations suggest systemic, neurogenic, or psychogenic etiologies. Group III presentations may result from any one of the previously mentioned etiologies or a mixed presentation. The classification also includes chronic pruritus of unknown origin, for which there are no known effective interventions.6 Pathognomonic skin findings and the extent of bodily involvement can also suggest certain diagnoses (Figure 17).

Common Dermatologic Etiologies of Pruritus

ATOPIC DERMATITIS

Atopic dermatitis is an inflammatory skin condition that is often associated with secondary lesions that result from scratching or other skin manipulation findings, such as excoriations, lichenification, and hyperpigmented or erythematous papules or plaques (Figure 2). Patients scratch pruritic areas and subsequently develop secondary lesions, worsening dermatitis and associated pruritus; this process is often called the itch-scratch cycle. Flexural areas are commonly affected, including ankles, regions behind the ears, and the antecubital and popliteal fossae. Patients with this condition often have a personal or family history of asthma or allergic rhinitis, and symptoms commonly begin during childhood. Treatment includes limiting exposure to water, liberal emollient use, and topical corticosteroid application.8,9

CONTACT DERMATITIS

Contact dermatitis is an inflammatory reaction that typically erupts within days of direct skin contact with an environmental trigger. Associated primary skin findings include bullae, vesicles, erythema, and edema, localized to areas that directly contacted the trigger. Irritant and allergic mechanisms are common. Irritant contact dermatitis is not immunologically mediated and progressively compromises the physical and chemical composition of the epidermis. In contrast, allergic contact dermatitis is dependent on a delayed hypersensitivity reaction and is more common in people with atopy. Contact dermatitis treatment includes avoidance of triggers, such as rough textiles, detergents, perfumes, chemicals, and dyes,1,4,10 and topical corticosteroid application.11

DERMATOPHYTOSIS

Tinea infections are caused by fungi that can survive only on dead keratin, including the most superficial layer of the epidermis (i.e., stratum corneum), hair, and nails. The characteristic ringworm rash appears as a well-demarcated region with a red, scaly, elevated border containing the highest concentration of fungal hyphae. Tinea pedis more often affects toe webs and soles of the feet, and the skin can become dry, scaly, fissured, or soft and macerated. Tinea capitis may present with patchy alopecia and scaling of the scalp. Onychomycosis is associated with dystrophic, discolored nails. Direct visualization of fungal hyphae on scale scrapings, hair shafts, and nail clippings prepared with potassium hydroxide solution aids in the diagnosis. Treatment includes topical and oral antifungals.12

INFESTATIONS AND INSECT BITES

Lice infestations often present on the scalp, pubic area, and body. Head lice commonly present in children, and pubic lice are sexually transmitted. Body lice live in the seams and folds of clothing. Physical examination findings associated with lice include direct visualization of adult organisms and their nits on hair shafts.13

Patients with scabies infestations typically report pruritus that worsens at night and can persist despite mite eradication. Skin findings common to scabies include burrows, vesicles, and papules in finger web spaces and axillae and on wrists, ankles, genitals, and extensor surfaces. Secondary skin lesions may be caused by scratching. Microscopic examination of skin scrapings may reveal scabies, mites, eggs, and feces.13

Insects commonly known to cause pruritic bites include mosquitoes, fire ants (Solenopsis), bed bugs (Cimex lectularius), gnats (Sciaridae), fleas (Siphonaptera), and chiggers (trombiculids). These insects injure the skin through stabbing mechanisms that expose the affected skin to the insect's saliva. An individual's allergic response to the injury and insect saliva determines the severity of the localized reaction. Patients with sensitive skin can quickly develop localized hypersensitivity reactions, including pruritic, erythematous urticarial papules and plaques.13

Treatment for infestations and insect bites is dependent on the causative species. For scabies and lice, permethrin is a first-line antiparasitic. N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide, also known as DEET, is the most effective insect repellent against biting insects. Treatment for insect bites includes symptom management with cool compresses, oral antihistamines, and topical corticosteroids.13

PSORIASIS

Psoriasis is a common chronic inflammatory skin disease that occurs because of a complex immune-mediated process that causes hyperproliferation of the skin, leading to scale and plaque formation. Psoriasis often develops at sites of skin trauma (Koebner phenomenon) and classically demonstrates pinpoint bleeding after removal of the scale overlying the plaque (Auspitz sign). Topical corticosteroids are the primary therapy for localized plaques; however, psoriatic pruritus can extend beyond the plaques. Liberal use of topical emollients can maintain skin moisture and suppleness, minimizing pruritus and subsequent trauma from scratching, ideally preventing the formation of new plaques.15

URTICARIA

Urticarial lesions (i.e., hives) are typically pruritic plaques with pale, centrally edematous wheals surrounded by erythematous flare regions (Figure 3). The lesions evolve or wax and wane over hours to days, are transient, change size and shape, and persist for less than 24 hours. Immunologic, autoimmune, and mechanical etiologies are possible. Examples include serum sickness and dermographism. Treatment of urticaria includes oral antihistamines.16

XEROSIS

Xerosis is dry, scaly skin that is more likely to occur in older adults because of excessive washing of the skin or during winter when homes are heated with relatively low humidity. Treatment of the associated pruritus should include using mild skin cleansers, avoiding excessive washing and abrasive scrubbing of the skin, applying skin moisturizers daily, and using a humidifier in the home.17

Common Systemic Etiologies of Pruritus

Systemic etiologies of pruritus should be considered in the absence of symptoms or findings suggestive of dermatologic disease (Table 2).4 Malignancy, including cervical, prostate, and colon cancers, can cause chronic generalized pruritus.1 Chronic conditions, including renal and hepatic failure, thyroid disease, diabetes mellitus, pregnancy, and multiple sclerosis, can also precipitate diffuse pruritus without concurrent skin disease. Psychogenic etiologies are diagnoses of exclusion; however, a history of emotional stress or chronic or transient psychiatric conditions may increase suspicion for pruritus.10,18

| Autoimmune Dermatitis herpetiformis Dermatomyositis Linear immunoglobulin A disease Sjögren syndrome Hematologic Hemochromatosis Iron deficiency anemia Mastocytosis Plasma cell dyscrasias Polycythemia vera Hepatobiliary Biliary cirrhosis Cholestasis Chronic pancreatitis with obstruction of biliary tracts Hepatitis (particularly hepatitis C) Sclerosing cholangitis Infectious disease Herpes zoster HIV/AIDS Human parvovirus B19 Parasitic disease (ascariasis, giardiasis, onchocerciasis, schistosomiasis) Prion disease Malignancy Cerebral tumor Leukemia Lymphoma Multiple myeloma Solid tumors with paraneoplastic syndrome Metabolic and endocrine Carcinoid syndrome Chronic renal disease Diabetes mellitus Hyperparathyroidism Thyroid disorders Neurologic Cerebral abscess Multiple sclerosis Nostalgia paresthetica Peripheral neuropathy Stroke Other Drug ingestion or eruption Eating disorders with rapid weight loss Neuropsychiatric disorders Pemphigoid gestationis Pruritic urticarial papules and plaques of pregnancy |

Clinical Evaluation

A detailed history helps build the differential diagnosis for pruritus (Table 3).4 An acute episode is less than six weeks, and a chronic presentation is six weeks or longer in duration.5 Physicians should inquire about the extent of bodily involvement; the frequency, quality, intensity, duration, and triggers of itching; and alleviating factors. Interview questions should also focus on topical, oral, and airborne exposures, such as detergents, hygiene products, occupational materials, illicit drug use, and medications (Table 4).19 Exposure duration and frequency may demonstrate other associations from hobbies, travel history, and sick contacts. Personal history or family history of skin disorders may suggest a predisposition to certain skin diseases. Systemic conditions should be suspected when pruritus is not accompanied by any reported or noticeable skin changes. A history of emotional stress and chronic psychiatric conditions increases consideration of a psychogenic etiology. Systemic symptoms, such as fever, fatigue, unintentional weight loss, and night sweats, are concerning for malignancy, particularly in older patients with chronic generalized pruritus without an obvious exposure association.4

| Historical finding | Possible etiologies |

|---|---|

| Hobby or occupational exposure to solvents, adhesives, cleaners | Irritant contact dermatitis, xerosis, atopic dermatitis, urticaria |

| Malaise, nausea, decreased urine output | Renal failure with generalized pruritus |

| New animal exposures | Flea infestation, allergic contact dermatitis, urticaria, dermatophytosis |

| New medications, supplements, or illicit drugs | Urticaria, drug eruptions |

| New skin or hair products (e.g., cosmetics, creams, soaps, detergents) | Allergic contact dermatitis, urticaria, photodermatitis |

| Personal or family history of atopic dermatitis, allergic rhinitis, or asthma; childhood onset; or prolonged water exposure | Atopic dermatitis |

| Recent travel | Pediculosis, scabies infestation, photodermatitis, urticaria |

| Sick contacts, especially people with febrile diseases and rashes | Rubeola, mumps, varicella, scarlet fever, cellulitis, fifth disease, folliculitis |

| Unexplained weight changes, menstrual irregularity, heat or cold intolerance | Thyroid disease with or without secondary urticaria or xerosis cutis |

| Unexplained weight loss, night sweats, unexplained fevers, fatigue | Malignancy, to include lymphoma with secondary generalized pruritus |

| Group of drugs | Examples | Possible mechanism | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antiarrhythmic drugs | Amiodarone | Cholestatic liver injury | Case reports |

| Antibiotics and chemotherapeutics | Antimalarials | Unknown, but release of histamine or activation of μ-receptors was postulated | Case reports |

| Carbapenems | Cholestatic liver injury | Rare | |

| Cephalosporins | Unknown or secondary to skin lesions | < 2% | |

| Lincosamides | Secondary to skin lesions or cholestatic liver injury | Rare | |

| Macrolides | Secondary to skin lesions or cholestatic liver injury | < 0.3% | |

| Metronidazole (Flagyl) | Unknown or secondary to skin lesions | < 5% | |

| Monobactams | Secondary to skin lesions | Rare | |

| Penicillins | Secondary to skin lesions or cholestatic liver injury | 2% to 20% | |

| Quinolones | Unknown or secondary to skin lesions | 1% to 4% | |

| Rifampin | Unknown | Case report | |

| Streptogramins | Secondary to skin lesions | 2.5% | |

| Tetracyclines | Unknown or cholestatic liver injury | 1% to 2% | |

| Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | Secondary to skin lesions | 2% to 10% | |

| Cholestatic liver injury | Rare | ||

| Anticoagulants | Fractionated heparins | Urticarial reaction | Case reports |

| Ticlopidine | Cholestatic liver injury | Case reports | |

| Antidiabetic drugs | Biguanides | Cholestatic liver injury | Case reports |

| Sulfonylurea derivatives | Unknown | < 5% | |

| Antiepileptics | Carbamazepine (Tegretol), fosphenytoin (Cerebyx), oxcarbazepine (Trileptal), phenytoin (Dilantin), topiramate (Topamax) | Secondary to skin lesions, allergic reaction | Rare |

| Antihypertensive drugs | Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors | Increase of bradykinin level or cholestatic liver injury or secondary to skin lesions | 1% to 15% |

| Angiotensin-II inhibitors (sartans) | Cholestatic liver injury | Case reports | |

| Beta-adrenergic blockers | Secondary to skin lesions Cholestatic liver injury | Frequent, if administered transdermally Rare | |

| Calcium channel blockers | Secondary to skin lesions or unknown Cholestatic liver injury | < 2% Case reports | |

| Methyldopa | Unknown or secondary to skin lesions | < 2% | |

| Sildenafil (Viagra) | Cholestatic liver injury | Case report | |

| Cytokines, growth factors, and monoclonal antibodies | Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor | Unknown | Common |

| Interleukin-2 | Direct pruritogenic effect of interleukin-2 | Very common | |

| Lapatinib (Tykerb) | Unknown or urticarial reaction | 3% | |

| Matuzumab (Leukeran) | Unknown | < 10% | |

| Cytostatics or chemotherapeutics | Chlorambucil | Secondary to skin lesions | Case reports |

| Paclitaxel (Taxol) | Unknown or secondary to skin lesions | 10% to 14% | |

| Tamoxifen | Sebostasis or xerosis | 3% to 5% | |

| Hypolipidemic drugs | Statins | Unknown or secondary to skin lesions | 16% |

| Plasma volume expanders | Hydroxyethyl starch | Deposition of hydroxyethyl starch in small peripheral nerves or in Schwann cells of cutaneous nerves | 12.6% to 54% |

| Psychotropic drugs | Neuroleptics | Cholestatic liver injury | Rare |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors | Activation of peripheral serotonin receptors or secondary to skin lesions | Rare | |

| Tricyclic antidepressants | Cholestatic liver injury | Rare | |

| Others | Antithyroid agents | Cholestatic liver injury | Rare |

| Corticosteroids | Cholestatic liver injury | Very rare | |

| Inhibitors of xanthine oxidase | Secondary to skin lesions | 0.8% to 2.1% | |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs | Increased synthesis of leukotrienes Cholestatic liver injury | 1% to 7% Rare | |

| Opioids | Centrally mediated process via μ-opioid receptor | 2% to 100% | |

| Sex hormones | Cholestatic liver injury | Rare |

The physical examination should include a complete dermatologic assessment, particularly for diffuse and chronic pruritus. Inspection of finger webs, the anogenital region, nails, and the scalp is suggested.1 During the assessment of skin lesions, primary lesions (i.e., present before the onset of pruritus) should be differentiated from reactive lesions (i.e., secondary to skin manipulation, including scratching, rubbing, or picking).5 If systemic disease is suspected, examination for lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly and additional diagnostic testing should be performed.

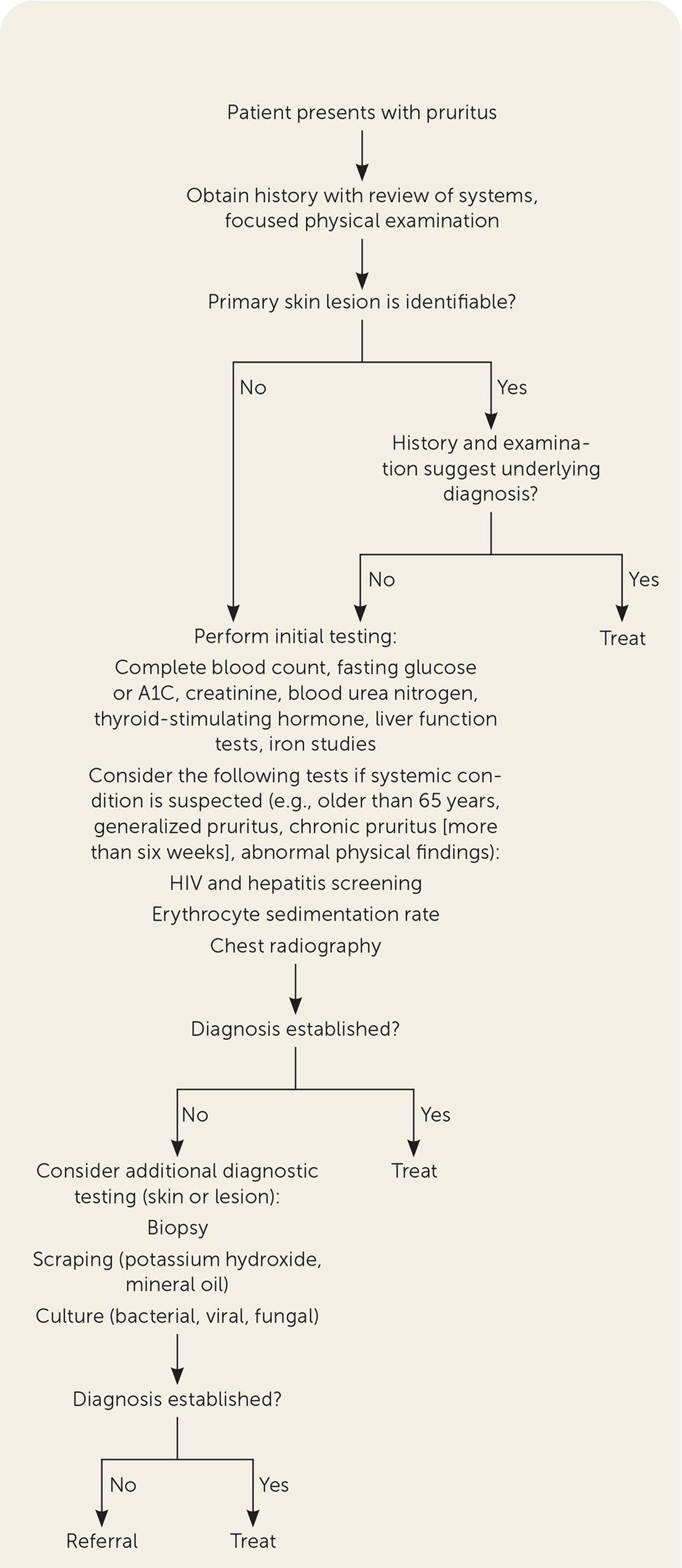

Diagnostic Approach

If an occult exposure or underlying etiology is not apparent on initial evaluation, physicians should consider other systemic causes (Table 24) by obtaining laboratory and imaging studies. Serologic testing should include a complete blood count with differential and iron studies because iron deficiency anemia is the most common cause of generalized pruritus in patients with underlying systemic disease.10 These studies can help identify other hematologic or malignant causes of pruritus, including polycythemia vera, hemochromatosis, and Hodgkin lymphoma. Serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen tests can assess for chronic kidney disease, and liver function tests can evaluate for hepatic and biliary etiologies. Fasting glucose, A1C, and thyroid-stimulating hormone tests can evaluate for diabetes and thyroid disorders.1,2,4,10

An erythrocyte sedimentation rate and chest radiography are appropriate if a systemic inflammatory condition or malignancy in an older patient is suspected. HIV screening is appropriate for individuals with increased risk based on history and physical examination.10

General Management

The determination of underlying etiologies affects treatment selection. Diagnosis and treatment of an underlying condition often resolves the associated pruritus. Although general management principles are provided in European guidelines, randomized controlled trials supporting these measures are lacking, and the recommendations are consensus based (Table 51,20–46). Dry skin and prolonged water exposure aggravate pruritus; liberal use of emollients is helpful, particularly following showering and bathing.1,2,4,47,48 Water exposure from bathing should not exceed a maximum of 20 minutes with lukewarm water, and the use of mild, perfume-free soaps and other hygiene products is recommended.1 Maintaining cool room temperatures at night can increase patient comfort while sleeping.1 Cooling wraps are an as-needed application option.1 Patient education promotes awareness of contact irritants and triggers1,4,10 (Table 14).

| General | |

| Keep skin cooler for comfort | Cool room temperatures at night1 Cool wraps, menthol, camphor, ice1 |

| Reduce skin drying effects | Limit bathing to 20 minutes with lukewarm water1 Limit soap use to oily and intertriginous areas1 |

| Medications | |

| Cholestatic hepatic disease | Cholestyramine (Questran)20 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors21 |

| Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy | Ursodeoxycholic acid22 |

| Lichen simplex chronicus | Salicylic acid or dichloromethane solution23 |

| Liver dysfunction related | Naltrexone (Revia)24 |

| Neuropathic pruritus | Gabapentin (Neurontin)25,26 Pregabalin (Lyrica)25,27 |

| Paraneoplastic syndrome | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors28 |

| Renal dysfunction related | Capsaicin29 Gabapentin, pregabalin30–33 Montelukast (Singulair)34 Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors35 Topical anesthetics (1% pramoxine hydrochloride)36 |

| Urticaria, allergic or atopic dermatitis | First- or second-generation antihistamines37,38 Topical naltrexone (1% cream)39 Topical steroids40,41 |

| Nonspecific | |

| Anti-inflammatory therapies* | Topical calcineurin inhibitors42 Topical corticosteroids1,43 |

| Nerve modulation | Systemic doxepin44 Topical doxepin†45 |

| Phototherapy | Narrowband ultraviolet B and ultraviolet A-146 |

Initial specific pharmacotherapy may include oral antihistamines for histamine-associated pruritic disorders or topical corticosteroids for pruritus associated with inflammatory dermatoses.1,2,37,38,40,41 Lifestyle modifications can include cognitive behavior therapy to address coping mechanisms.1,49 Frequent follow-up is recommended to assess responses to treatment modalities.

Specialist consultation is reasonable if a cause is uncertain after the initial evaluation and additional diagnostic testing or if a patient is symptomatic following appropriate first-line treatment modalities for an underlying condition.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Reamy, et al.,4 and Moses.7

Data Sources: PubMed and Cochrane databases were searched using key terms including pruritus and itch. The search included randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses, clinical trials, and clinical reviews. An Essential Evidence Plus summary report on this topic was reviewed and utilized to assist in literature review. Search dates: September 2020, October 2020, and August 2021.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Air Force or the Department of Defense.