Am Fam Physician. 1999;59(4):945-952

Patients with a diagnosis of acute deep venous thrombosis have traditionally been hospitalized and treated with unfractionated heparin followed by oral anticoagulation therapy. Several clinical trials have shown that low-molecular-weight heparin is at least as safe and effective as unfractionated heparin in the treatment of uncomplicated deep venous thrombosis. The use of low-molecular-weight heparin in an outpatient program for the management of deep venous thrombosis provides a treatment alternative to hospitalization in selected patients. Use of low-molecular-weight heparin on an outpatient basis requires coordination of care, laboratory monitoring, and patient education and participation in treatment. Overlapping the initiation of warfarin permits long-term anticoagulation. Advantages include a decreased incidence of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia and fewer episodes of bleeding complications. Future clinical trials evaluating the safety and efficacy of low-molecular-weight heparin in the treatment of complicated deep venous thrombosis will further define appropriate indications for use and strategies for outpatient management.

Deep venous thrombosis (DVT) is associated with more than 600,000 hospitalizations annually in the United States and results in more than 200,000 deaths caused by pulmonary embolism.1 Patients with a diagnosis of acute DVT have traditionally been hospitalized and treated with a continuous infusion of unfractionated heparin for five to 10 days, followed by oral anticoagulation therapy for at least three months. Hospitalization has traditionally been considered necessary because of concerns about fatal pulmonary embolism (and the need for careful laboratory monitoring), but this risk is now known to be low during the initial treatment of DVT.2 Because of the wide variability in anticoagulant response among patients treated with unfractionated heparin, frequent monitoring of the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) and dosage adjustments are required to keep anticoagulation in the therapeutic range. In most patients who have no major risk factors for bleeding or subsequent pulmonary embolism, such as protein C or S deficiency, history of previous pulmonary embolism or more proximal DVT, hospitalization is necessary only for monitoring aPTT and adjusting unfractionated heparin therapy.

Several clinical trials have shown that low-molecular-weight heparins are at least as safe and effective as unfractionated heparin in the treatment of DVT.3–6 These agents have a longer half-life and a more predictable anticoagulant response than unfractionated heparin, which allows for subcutaneous administration without laboratory monitoring.7 The use of low-molecular-weight heparins in the treatment of DVT provides an opportunity to realize significant cost savings by preventing or shortening hospitalization and by increasing patient comfort and satisfaction with health care.8 Shifting the management of DVT to the ambulatory setting presents several clinical and logistical challenges for clinicians, administrators and patients. The success of an out-patient program for the management of DVT depends on familiarity with currently available low-molecular-weight heparins, patient selection, protocol development and outcome evaluation.

Low-Molecular-Weight Heparins

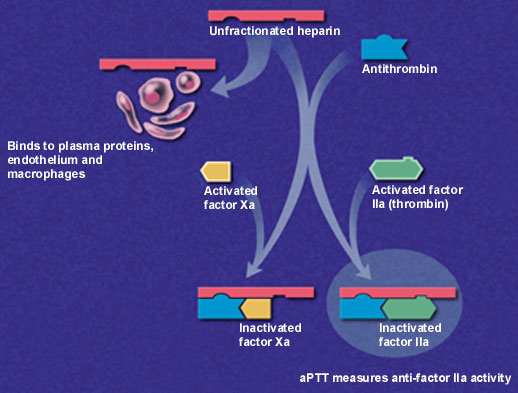

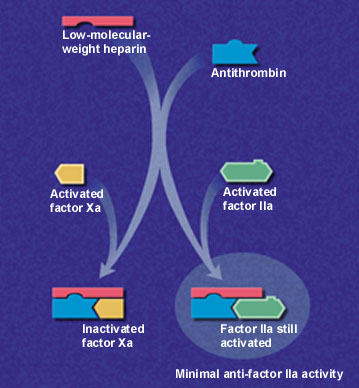

Low-molecular-weight heparins are derived from depolymerization of standard heparin, which yields fragments approximately one third the size of the parent compound. These lower-molecular-weight fractions have several properties that differentiate them from unfractionated heparin. Low-molecular-weight heparins exert their anticoagulant effect by inhibiting factor Xa and augmenting tissue-factor-pathway inhibitor but minimally affect thrombin, or factor IIa (Figure 1a and 1b). Thus, the aPTT, a measure of antithrombin (anti-factor IIa) activity, is not used to measure the activity of low-molecular-weight heparins, which requires instead a specific anti-Xa assay.

In addition to having lower antithrombin activity than unfractionated heparin, low-molecular-weight heparins bind less to plasma proteins, endothelium and macrophages, permitting greater bioavailability and little inter-patient and intra-patient variability in response to a given dosage.9 Clinical trials have confirmed that effective antithrombotic activity can be consistently achieved by calculating dosages based on body weight without the need for laboratory monitoring.10

Since these agents are eliminated primarily through the kidneys, accumulation of anti-factor Xa activity may occur in patients with chronic renal insufficiency. Plasma anti-factor Xa concentrations should be monitored in patients with renal dysfunction and possibly in those weighing less than 50 kg (110 lb) or more than 80 kg (176 lb).10 Low-molecular-weight heparins also appear to be associated with less bleeding and a decreased frequency of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, as a result of their lower affinity for platelets and von Willebrand factor.10 Danaparoid (Orgaran) and lepirudin (Refludan) are indicated in the treatment of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia type II. Lepirudin is a recombinant form of hirudin, an anticoagulant derived from the saliva of leeches. Danaparoid is a low-molecular-weight heparin composed of a mixture of heparan, dermatan and chondroitin sulfates.

Low-molecular-weight heparins currently available in the United States include enoxaparin (Lovenox), dalteparin (Fragmin) and ardeparin (Normiflo), while nadroparin (Fraxiparine), tinzaparin (Logiparin, Innohep) and reviparin (Clivarine) are marketed elsewhere (Table 1). Enoxaparin was recently labeled by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for outpatient treatment of DVT and may also be used in the inpatient setting to manage DVT with or without pulmonary embolism. Each of these agents is prepared with a different method of depolymerization, resulting in distinct molecular weights (4,000 to 5,500 Da) and relative effects on factor Xa and thrombin. For this reason, low-molecular-weight heparins are unique and not necessarily therapeutically interchangeable, although their pharmacologic and clinical characteristics are similar.10

| Agent | Clinical trial treatment doses (anti-Xa units) | Average molecular weight (Da) | Intravenous half-life (minutes) | Cost* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ardeparin (Normiflo)† | Not evaluated | 6,000 | 200 | $154.50‡ |

| Dalteparin (Fragmin)† | 100 U per kg twice daily | 5,000 | 119 to 139 | 63.00§ |

| Enoxaparin (Lovenox)† | 100 U per kg twice daily | 4,500 | 129 to 180 | 78.50 |

| Nadroparin (Fraxiparine) | 225 U per kg twice daily | 4,500 | 132 to 162 | NA |

| Reviparin (Clivarine) | 100 U per kg twice daily | 4,300 | NA | NA |

| Tinzaparin (Logiparin, Innohep) | 175 U per kg once daily | 4,900 | 111 | NA |

| Danaparoid ∥ (Orgaran) | 750 U twice daily | 5,500 | 24 hours | 237.00§ |

Several meta-analyses have indicated that low-molecular-weight heparins are superior to unfractionated heparin in the treatment of patients with established DVT. One analysis did not indicate a significant difference in symptomatic recurrence rates or adverse events but did note trends favoring low-molecular-weight heparins.11 The safety and effectiveness of these agents were significantly better than that of unfractionated heparin in two other analyses.12,13 Collectively, the results reveal a statistically significant reduction in thrombus size, recurrent venous thromboembolism, major bleeding events and pooled long-term mortality rate. Although the lower mortality rates observed in these trials were mostly attributable to a subgroup of patients with cancer, the data may indicate greater efficacy of low-molecular-weight heparins in this high-risk population.14

Two recent studies of patients with DVT have also been conducted to compare the effect of low-molecular-weight heparins given on an outpatient basis subcutaneously twice daily with that of unfractionated heparin given by continuous intravenous infusion in the hospital.15,16 No significant difference was found in rates of recurrent venous thromboembolism, hemorrhagic complications, development of thrombocytopenia or mortality. Low-molecular-weight heparins were as safe and effective as unfractionated heparin, and most patients were managed at home immediately after diagnosis or a brief hospitalization.

In addition to comparable efficacy in the treatment of DVT, patients receiving low-molecular-weight heparin reported a higher quality of life in terms of physical and social function and sense of well-being. Treatment of DVT with low-molecular-weight heparin was more cost-effective than therapy with unfractionated heparin because the length of the hospital stay was reduced by 60 to 70 percent without an increase in the cost of home health care.

Patient Selection

Criteria are needed for the selection of patients who may be candidates for low-molecular-weight heparin therapy on an ambulatory basis. The studies15,16 evaluating the effectiveness of low-molecular-weight heparins in the treatment of DVT excluded certain patient populations (Table 2). Based on selection criteria from these clinical trials, approximately 40 percent of all patients diagnosed with DVT would be eligible for home-based treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin.15,16

| Clinical evidence of pulmonary embolism or suspected embolism | |

| Conditions that increase the risk of bleeding: | |

| Recent surgery | |

| Peptic ulcer disease | |

| Malignant hypertension | |

| Increased risk of falling | |

| High risk of recurrent thrombosis: | |

| Extensive proximal deep venous thrombosis | |

| Recurrent deep venous thrombosis | |

| Pregnancy | |

| Protein C or S deficiency | |

| Likelihood of noncompliance | |

| Unavailable for follow-up | |

| Inadequate home support system | |

While the safety and efficacy of low-molecular-weight heparin in the treatment of patients with DVT alone is clear, controversy surrounds its use in the hospital and at home in patients with documented or suspected pulmonary embolism. A recent study17 evaluating once-daily administration of tinzaparin compared with unfractionated heparin in the treatment of acute pulmonary embolism found no difference in rates of combined recurrent thromboembolism, major bleeding or death. However, low-molecular-weight heparin was not given on an outpatient basis in that study, and the results cannot be extrapolated to patients who take these agents at home.

The Columbus study18 compared low-molecular-weight heparin, given twice daily, with unfractionated heparin in patients with DVT, with or without pulmonary embolism or history of venous thromboembolism. Twenty-seven percent of the patients who were randomized to the low-molecular-weight heparin arm of this trial were managed outside the hospital. Both treatment groups were similar in the incidence of recurrent thromboembolic events, episodes of major bleeding and mortality. While further study is warranted to determine if patients with DVT and suspected pulmonary embolism may be safely and effectively treated with low-molecular-weight heparin in the ambulatory setting, the evidence in favor of this therapy is mounting rapidly.19 At present, outpatient low-molecular-weight therapy is best reserved for use in patients with uncomplicated DVT, a competent caregiver at home or the ability for self-care, and an appropriate mechanism for follow-up with their family physician (Figure 2).

Development of Protocol

A multidisciplinary approach is necessary to develop the specific details of an outpatient management protocol for DVT. Physicians, nurses, pharmacists and other health care professionals each contribute a unique perspective in planning and implementing a program protocol for managing patients with low-molecular-weight heparin therapy on an outpatient basis.

In addition to cost, drug selection and other pharmaceutical factors should be discussed before protocol implementation.20 No evidence indicates that any one low-molecular-weight heparin is more effective or safer than another in the treatment of DVT on an outpatient basis. Drug selection is often dictated by ease and frequency of administration, cost and evaluation of the safety and efficacy of each agent based on the results of clinical trials.

All low-molecular-weight heparins are packaged in syringes containing smaller, prophylactic doses, so repackaging is necessary to provide the appropriate treatment dosage as a single injection. New unit-dose syringes for several agents used for the treatment of DVT have just been approved or are awaiting FDA approval. Information about the stability and compatibility of low-molecular-weight heparins should be obtained from the manufacturer or other sources to ensure proper preparation and storage of these agents. These agents may be dispensed by outpatient pharmacies to patients for self-administration at home or prepared by home health care professionals delivering care directly to the patient.

An outpatient management protocol for DVT should include information on antithrombotic therapy, laboratory monitoring, patient activity, nonpharmacologic management and patient education.21 After the diagnosis of DVT is confirmed, many patients may be treated on an ambulatory basis. If the patient or a family member is unable to administer low-molecular-weight heparin, the physician should arrange for home health care if the patient is eligible. Antithrombotic therapy should be started on the first day of therapy and should include at least five days of treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin overlapping from the first day of treatment with warfarin (Coumadin). The average starting dosage of warfarin is 5 mg daily in most patients, except the elderly and those with hepatic disease, who require a lower dosage.

Determination of activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) to rule out clotting abnormalities and prothrombin time/International Normalized Ratio (PT/INR), and a complete blood cell count with platelets should be obtained at baseline, as well as a platelet count on the fifth day of therapy. An INR should be obtained on the third day and again daily until low-molecular-weight heparin therapy is discontinued. Therapy with low-molecular-weight heparin may be discontinued after at least five days of therapy once the INR is between 2.0 and 3.0. In the majority of patients whose risks for recurrent thromboembolism are low, three months of warfarin therapy usually suffice. In patients with an ongoing risk of thrombosis (e.g., cancer, hereditary clotting diathesis), longer or even life-long therapy may be indicated.9

Patients should reduce their level of activity as long as pain persists and elevate the extremities when possible during the first two days of therapy.21 Local therapy should be instituted on the first day and include application of local heat and range-of-motion exercises. The treatment protocol should also include an inpatient option for initiation of therapy. Patients admitted to the hospital with a new diagnosis of DVT may receive one to four days of therapy with unfractionated heparin plus oral warfarin before starting treatment with low-molecular-weight heparin. Therapy with low-molecular-weight heparin should be initiated within one hour of discontinuing intravenous administration of unfractionated heparin. Whether DVT is managed with low-molecular-weight heparin in an outpatient or inpatient setting, intensive patient education is required to ensure a positive therapeutic outcome.

Physicians involved with the DVT program are responsible for providing education to patients who receive outpatient therapy (Table 3). Patients should be taught the proper technique for administering low-molecular-weight heparin, indications for heparin and warfarin therapy, medication side effects and potential drug interactions. The first dose of low-molecular-weight heparin should be given in the clinic to ensure patient tolerance and demonstrate appropriate injection technique.

| Clinical monitoring | |

| Baseline: | |

| Hemoglobin | |

| Hematocrit | |

| Platelet count | |

| aPTT | |

| PT/INR | |

| DVT symptoms | |

| During low-molecular-weight heparin treatment: | |

| PT/INR— goal: 2.0 to 3.0 | |

| Warfarin (Coumadin)— initial dosage: 2.5 to 5.0 mg daily | |

| Platelet count | |

| DVT symptoms | |

| Medication administration problems | |

| Bleeding | |

| PE symptoms (chest pain, shortness of breath) | |

| Noncompliance | |

| Patient education | |

| Drug description and use | |

| Treatment duration (5 to 7 days) | |

| Side effects | |

| Dosing (Table 1) | |

| Injection site selection | |

| Injection technique | |

| Injection site monitoring | |

| Drug interactions | |

| Handling of missed doses and overdoses | |

| Storage requirements | |

| Syringe disposal | |

| First-dose demonstration | |

Kits with a sharps container, alcohol pads and instructions for administration may be useful. Physicians should instruct patients about the necessary monitoring of the drug, the injection site and DVT, give guidelines for seeking additional medical assistance and outline necessary follow-up appointments. If possible, written materials, information packets and audiovisual aids should be given to patients to reinforce the learning process. Patient education materials are available from manufacturers of some low-molecular-weight heparins. The extent of program education should be documented in the patient's medical record.

Outcome Evaluation

Patients should be closely monitored during and after completion of the treatment protocol. Significant bleeding events, episodes of recurrent thrombosis (e.g., DVT, pulmonary embolism), other symptoms and any problems with medication administration should be documented.

As for cost considerations, economic appraisals of DVT therapy with low-molecular-weight heparins compared with unfractionated heparin have shown a 20 percent reduction in disease management costs attributable to decreased length of hospital stay and an average cost savings of over $900 per patient.8,22