A more recent article on multiple sclerosis is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2004;70(10):1935-1944

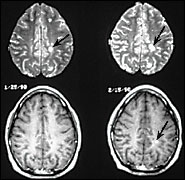

Multiple sclerosis, an idiopathic inflammatory disease of the central nervous system, is characterized pathologically by demyelination and subsequent axonal degeneration. The disease commonly presents in young adults and affects twice as many women as men. Common presenting symptoms include numbness, weakness, visual impairment, loss of balance, dizziness, urinary bladder urgency, fatigue, and depression. The diagnosis of multiple sclerosis should be made by a physician with experience in identifying the disease. Diagnosis should be based on objective evidence of two or more neurologic signs that are localized to the brain or spinal cord and are disseminated in time and space (i.e., occur in different parts of the central nervous system at least three months apart). Magnetic resonance imaging with gadolinium contrast, especially during or following a first attack, can be helpful in providing evidence of lesions in other parts of the brain and spinal cord. A second magnetic resonance scan may be useful at least three months after the initial attack to identify new lesions and provide evidence of dissemination over time. It is critical to exclude other diseases that can mimic multiple sclerosis, including vascular disease, spinal cord compression, vitamin B12 deficiency, central nervous system infection (e.g., Lyme disease, syphilis), and other inflammatory conditions (e.g., sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome). Symptom-specific drugs can relieve spasticity, bladder dysfunction, depression, and fatigue. Five disease-modifying treatments for multiple sclerosis have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. These treatments are partially effective in reducing exacerbations and may slow progression of disability.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) typically presents in adults who are 20 to 45 years of age. Occasionally, the disease presents in childhood or late middle age. Twice as many women are affected as men, and persons of Northern European descent appear to be at highest risk for the disease.

| Key clinical recommendation | Label | References |

|---|---|---|

| Magnetic resonance imaging should be performed or repeated three months after a clinically suspicious episode to facilitate early diagnosis of MS. | C | 1 |

| Corticosteroid therapy should be used to shorten the duration of MS relapses and accelerate recovery. | A | 16 |

| Disease-modifying treatment should be started early in the course of MS to minimize irreversible axonal damage. | C | 35 |

| Glatiramer and the beta interferons have different mechanisms of action. Patients with MS who have an unsatisfactory response to beta interferons should be considered for glatiramer therapy. | C | 23 |

| Patients with worsening forms of MS may be referred for mitoxantrone therapy; however, this agent has acute short-term adverse effects, as well as serious long-term adverse effects that include cardiotoxicity. | B | 26 |

The onset of MS may be insidious or sudden. Common presenting symptoms include monocular visual impairment with pain (optic neuritis), paresthesias, weakness, and impaired coordination (Table 1). Frequent accompanying signs and symptoms include bladder urgency or retention, constipation, sexual dysfunction, fatigue, depression, diplopia, gait and limb ataxia, and Lhermitte’s sign (electrical sensation down the spine on neck flexion).

| Symptoms |

| Depression |

| Dizziness or vertigo |

| Fatigue |

| Heat sensitivity |

| Lhermitte’s sign (electrical sensation down the spine on neck flexion) |

| Numbness, tingling, pain |

| Urinary bladder dysfunction |

| Visual impairment (monocular or diplopia) |

| Weakness |

| Signs |

| Action tremor |

| Decreased perception of pain, vibration, or position |

| Decreased strength |

| Hyperreflexia, spasticity, Babinski’s sign |

| Impaired coordination and balance |

| Impaired visual acuity or red color perception with optic disc pallor and afferent pupillary defect; disconjugate eye movements |

| Nystagmus |

MS frequently is overlooked because initial symptoms resolve spontaneously in most patients. Relapses occur within months or years. In some patients, however, MS has a primary progressive course from onset.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of MS is based on the presence of central nervous system (CNS) lesions that are disseminated in time and space (i.e., occur in different parts of the CNS at least three months apart), with no better explanation for the disease process. Because no single test is totally reliable in identifying MS, and a variety of conditions can mimic the disease (Table 2), diagnosis depends on clinical features supplemented by the findings of certain studies.

| CNS infection (e.g., Lyme disease, syphilis, human immunodeficiency virus infection, human T-lymphotrophic virus type I) |

| CNS inflammatory condition (e.g., sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome) |

| CNS microvascular disease (e.g., disease caused by hypertension, diabetes mellitus, vasculitis, CADASIL) |

| Genetic disorder (e.g., leukodystrophy, hereditary myelopathy, mitochondrial disease) |

| Structural or compressive condition of the brain and spinal cord (e.g., cervical spondylosis, tumor, herniated disc, Chiari’s malformation) Vitamin B12 deficiency |

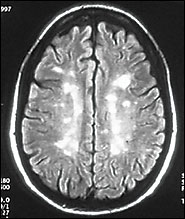

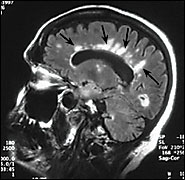

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been shown to be highly sensitive in detecting clinically silent MS plaques. Consequently, findings of this imaging modality are included in diagnostic criteria that have been proposed by one set of investigators.1 The major advantage of the proposed criteria is that an early diagnosis of MS can be made if an MRI scan performed three months after a clinically isolated attack demonstrates formation of a new lesion. The proposed diagnostic criteria also define MRI lesion characteristics that increase the likelihood of MS, including number of lesions (nine or more), location of lesions (position abutting the ventricles; juxtacortical, infratentorial, or spinal position), and lesion enhancement with the use of contrast medium (Table 3).

| Brain lesions |

| High signal on T2-weighted and FLAIR MRI sequences (more than nine lesions) |

| When actively inflamed, often enhanced with gadolinium contrast |

| Position abutting ventricles (often perpendicular) |

| Juxtacortical position (gray-white junction) |

| Involvement of brainstem, cerebellum, or corpus callosum |

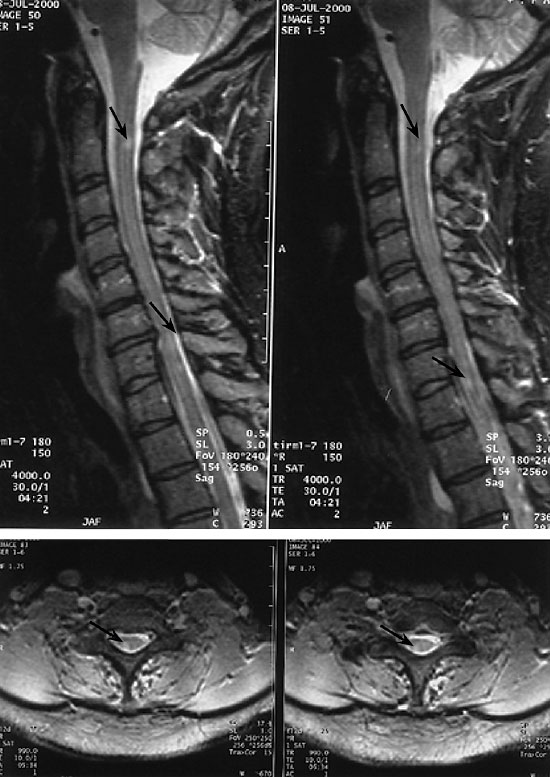

| Spinal cord lesions |

| One or two vertebral segments in length |

| Incomplete cross-sectional involvement (dorsolateral common) |

| Less likely to enhance with gadolinium contrast |

| No cord swelling |

| Better seen with STIR MRI sequences |

CONFIRMATORY STUDIES

CNS Imaging

A brain MRI scan is the most useful test for confirming the diagnosis of MS.1 MS lesions appear as areas of high signal, predominantly in the cerebral white matter or spinal cord, on T2-weighted images (Figures 1 through 4). MRI scanning is useful for detecting structural pathology in regions that can be difficult to image by computed tomography, such as the posterior fossa, craniocervical junction, and cervical cord.2 A brain MRI scan performed with a high-field magnet (1.5 tesla or greater) is abnormal in almost all patients who have clinically definite MS.

Sensory Evoked Potential Testing

Evoked potentials (visual, brainstem auditory, and somatosensory) may be useful in demonstrating the presence of subclinical lesions in sensory pathways or in providing objective evidence of lesions suspected on the basis of subjective complaints.3 Of the sensory evoked potential tests, the visual evoked potential is the most useful because it can provide objective evidence of an optic nerve lesion that may not be evident on an MRI scan.

Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Analysis

In approximately 90 percent of patients with definite MS, the CSF IgG concentration is increased relative to other CSF proteins (e.g., albumin), and CSF gel electrophoresis reveals oligoclonal bands that are not present in a matched serum sample.4 However, an increased CSF IgG index and the presence of oligoclonal bands are not specific for MS and therefore are not diagnostic of the disease. CSF analysis probably is most useful for ruling out infectious or neoplastic conditions that mimic MS.

Serologic Testing

Peripheral blood tests may be helpful in excluding other disease processes. Testing frequently includes determination of the vitamin B12 level, thyroid-stimulating hormone level, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and anti-nuclear antibody titers, as well as a test for Lyme disease, and a test for syphilis (rapid plasma reagin test).

In unusual cases, a more extensive evaluation may include tests for anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, anti-phospholipid antibodies, Sjögren’s syndrome A and B, angiotensin-converting enzyme, human T-lymphotrophic virus type I, and very long chain fatty acids (for adrenoleukodystrophy). Rarely, human immunodeficiency virus infection and opportunistic infections can mimic MS.

DIAGNOSTIC ERROR

Certain clinical or laboratory red flags should alert physicians to a possible diagnostic error.5 These flags include symptoms that could be explained by localized disease; the presence of steadily progressive disease; the absence of clinical remission; the absence of oculomotor, optic nerve, sensory, or bladder involvement; and normal CSF findings. However, none of these findings excludes the diagnosis of MS.

Management

SYMPTOMATIC THERAPIES

Spasticity

Mild spasticity may be managed by stretching and exercise programs such as water therapy, yoga, and physical therapy. Medication is indicated when stiffness, spasms, or clonus interferes with function or sleep. Baclofen (Lioresal), tizanidine (Zanaflex), gabapentin (Neurontin), and benzodiazepines are effective antispastic agents6 (Table 4). Intrathecal baclofen therapy has a major impact on medically intractable spasticity and has largely supplanted chemical rhizotomy or myelotomy.7

| Symptom | Therapy and possible adverse effects |

|---|---|

| Spasticity | Baclofen (Lioresal), 10 to 40 mg three times daily; in high doses, can cause weakness and fatigue |

| Tizanidine (Zanaflex), 2 to 8 mg three times daily; in high doses, can cause weakness and fatigue | |

| Gabapentin (Neurontin), 300 to 900 mg three or four times daily; in high doses, causes fatigue | |

| Pain and paroxysmal disorders | Gabapentin, 300 to 900 mg three or four times daily; in high doses, causes fatigue |

| Carbamazepine (Tegretol), 100 to 600 mg three times daily; in high doses, causes rash and neurologic side effects; requires monitoring of complete blood count and liver function | |

| Other anticonvulsants | |

| Amitriptyline (Elavil), 10 to 150 mg per day at bedtime | |

| Bladder urgency | Oxybutynin (Ditropan), 5 mg once daily to 20 mg per day in divided doses; causes dry mouth and can exacerbate glaucoma or worsen urinary retention |

| Tolterodine (Detrol), 2 to 4 mg twice daily; causes dry mouth and can exacerbate glaucoma or worsen urinary retention (these side effects occur less often than with oxybutynin) | |

| Depression | SSRIs preferred because of activating properties; can have sexual side effects |

| Alternatives to SSRIs when sexual side effects occur: extended-release venlafaxine (Effexor) 75 to 225 mg per day, or sustained-release bupropion (Wellbutrin), 150 mg per day to 150 mg twice daily | |

| Third-line drug or for use when a patient has a sleep disorder or concomitant headaches: amitriptyline, 10 to 150 mg per day at bedtime | |

| Fatigue | Amantadine (Symmetrel), 100 mg twice daily; can cause rash, edema, and anticholinergic effects |

| Modafinil (Provigil), 100 to 200 mg given in the morning; can cause jittery sensation and palpitations | |

| SSRIs, can have sexual side effects |

Paroxysmal Disorders

Bladder Dysfunction

In patients with new bladder symptoms, urinalysis and culture should be performed to rule out infection, with appropriate treatment provided if needed. The first step in medical management of the neurogenic bladder is to determine whether the problem is a failure to empty urine or a failure to store urine. The history may or may not be helpful. A postvoid residual urinary volume is the best means of determining urinary retention.

The anticholinergic drugs oxybutynin (Ditropan) and tolterodine (Detrol) are effective for symptoms of failure to store urine (in the absence of infection or overflow incontinence).10

Drug treatment of urinary retention usually is ineffective, although some patients benefit from attempts to decrease bladder neck tone using an alpha1-adrenergic receptor antagonist such as terazosin (Hytrin), doxazosin (Cardura), or tamsulosin (Flomax).11 Bethanechol (Urecholine) may be helpful in patients with a flaccid bladder.

Definitive treatment of urinary retention involves teaching the patient to perform intermittent self-catheterization, if possible. In some patients, inhaled desmopressin (DDAVP) can be used to suppress nocturnal urinary production.

Bowel Symptoms

Constipation is common in patients with MS. It should be managed aggressively to avoid long-term complications.

Fecal incontinence is rare; when it occurs, the addition of fiber can provide enough bulk to the stool to allow a partially incompetent sphincter to hold in the bowel movement long enough for the patient to reach a bathroom. Short-term use of anticholinergics or antidiarrheal agents may be effective in combating incontinence associated with diarrhea.

Sexual Symptoms

A careful sexual history may reveal problems such as feelings of sexual inadequacy, impaired libido, or direct sexual dysfunction resulting from erectile dysfunction, impaired lubrication, spasticity, or heat-related sensory dysesthesias. Counseling, a review of the sexual side effects of medications, and medical therapy may be appropriate. In some patients with MS, erectile dysfunction can be managed effectively with sildenafil (Viagra).12

Neurobehavioral Manifestations

Depression occurs in more than one half of patients with MS.13 Patients with mild, transient depression can be cared for with supportive measures. Those with more severe depression should be treated with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which are less sedating than other antidepressants. Bedtime administration of amitriptyline can be useful in depressed patients who also are having difficulty sleeping or have headaches or other pain syndromes.

Fatigue

This symptom often responds to rest or medication. Amantadine (Symmetrel), 100 mg twice daily, may be effective.14 Modafinil (Provigil), a narcolepsy drug that acts as a CNS stimulant, has been found to be effective in patients with MS; the drug is given in a dosage of 200 mg once daily in the morning.15 Occasionally, SSRIs can relieve fatigue in patients with MS. Amantadine has the added advantage of having anti–influenza-A properties and may be given from October to March.

RELAPSES

In a patient with an apparent relapse of MS, it is important to rule out a treatable infection such as sinusitis, bronchitis, or urinary tract infection.

Adrenal Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are the mainstay of symptomatic relief for an acute relapse of MS. These agents work through immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory effects, restoration of the blood-brain barrier, and reduction of edema. They also may improve axonal conduction. Corticosteroid therapy shortens the duration of acute relapses and accelerates recovery. However, corticosteroids have not been shown to improve the overall degree of recovery or to alter the long-term course of MS.16

If a patient is having acute disability from an attack, the physician should consider treatment with a three- to five-day course of intravenous methylprednisolone (or equivalent corticosteroid) in a dosage of 1 g administered intravenously in 100 mL of normal saline over 60 minutes once daily in the morning.

Other Treatments

In patients with MS, physical therapy always should be considered because it improves function and quality of life independent of drug therapy.17 Supportive care in the form of counseling, occupational therapy, advice from social workers, input from nurses, and participation in patient support groups are all part of a united health care team approach to the management of MS. Some patients require temporary disability status.

Patients with MS often are tempted to try alternative therapies such as special diets, vitamins, bee stings, a compound “off-label” transdermal medication (i.e., Prokarin), or acupuncture. Although definitive proof of the effectiveness of these treatments in MS is lacking, patients sometimes use them in a complementary fashion. Sole reliance on alternative therapies should be discouraged because patients then may be deprived of therapies that have been shown to be effective in the treatment of MS.

DISEASE-MODIFYING THERAPIES

Four disease-modifying therapies for the initial management of MS are available in the United States: intramuscular interferon beta-1a (Avonex), subcutaneous interferon beta-1a (Rebif), interferon beta-1b (Betaseron), and glatiramer acetate (Copaxone). A fifth agent, mitoxantrone (Novantrone), has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of worsening forms of relapsing-remitting MS and secondary progressive MS (Table 5).

| Drug | Dosage | Side effects and monitoring | Cost for 1 month of treatment* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Interferon beta-1a (Avonex) | 30 mcg IM once weekly | Influenza-like symptoms | $1,278 |

| Monitoring of CBC and liver function | |||

| Interferon beta-1a (Rebif) | 22 to 44 mcg SC three times weekly | Influenza-like symptoms and injection-site reactions | 1,517 |

| Monitoring of CBC and liver function | |||

| Interferon beta-1b (Betaseron) | 0.25 mg SC every other day | Influenza-like symptoms and injection-site reactions | 1,403 |

| Monitoring of CBC and liver function | |||

| Glatiramer (Copaxone) | 20 mg SC once daily | Injection-site reactions and, rarely, a benign systemic reaction | 1,261 |

| Requires no blood monitoring | |||

| Mitoxantrone (Novantrone) | 5 to 12 mg per m2 IV every 3 months | Mild chemotherapy-related side effects, cumulative cardiotoxicity, small increased risk of leukemia | 1,453 |

Beta Interferons

The beta interferons are naturally occurring cytokines with a variety of immunomodulating and antiviral activities that may account for their therapeutic effects. The three FDA-approved beta interferons that are used for MS have been shown to reduce relapses by about one third and are recommended as first-line therapy or for use in glatiramer-intolerant patients who have relapsing-remitting MS.18 In randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled trials,19–21 use of beta interferons resulted in a 50 to 80 percent reduction in inflammatory lesions visualized on brain MRI scans. There also is evidence that these drugs improve quality of life and cognitive function.22,23

The major difference in the beta interferon drugs is that intramuscular interferon beta-1a is given once a week and subcutaneous interferon beta-1a and interferon beta-1b are given three times a week, or every other day, respectively. The adequacy of weekly dosing has been questioned.24,25 There appears to be a modest dose-response effect with the beta interferons.24 One study26 of double-dose (60-mcg) intramuscular interferon beta-1a administered once a week found no benefit over the single-dose regimen. Whether the benefit of more frequent dosing is sustained remains unclear. An increased incidence of neutralizing antibodies with the more frequent subcutaneous dosing also must be considered.

Influenza-like symptoms, including fever, chills, malaise, muscle aches, and fatigue, occur in approximately 60 percent of patients treated with interferon beta-1a or interferon beta-1b. These symptoms usually dissipate with continued therapy and premedication with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug. Dose titration at the initiation of beta interferon therapy also is a useful strategy.

Other side effects of the beta interferons include injection-site reactions, worsening of pre-existing spasticity, depression, mild anemia, thrombocytopenia, and elevated transaminase levels. These side effects usually are not severe and rarely lead to discontinuation of treatment.

Treatment with any beta interferon can result in the development of neutralizing antibodies. Although study results are variable, once-weekly intramuscular interferon beta-1a therapy has been reported to have the lowest incidence of neutralizing antibody development.27 The effect of neutralizing antibodies on the long-term efficacy of beta interferon therapy remains to be fully defined because titers and durations of antibody positivity (some neutralizing antibodies resolve with time) are variable.

Glatiramer

This drug is a polypeptide mixture that was originally designed to mimic and compete with myelin basic protein. Its mechanism of action is distinct from that of the beta interferons; therefore, patients may respond differently to the drug. Glatiramer in a dosage of 20 mg administered subcutaneously once daily has been shown to reduce the frequency of MS relapses by approximately one third. The drug also is recommended as a first-line treatment in patients with relapsing-remitting MS and in the treatment of patients who cannot tolerate beta interferon therapy.28 Glatiramer therapy results in a one-third reduction in the inflammatory activity seen on MRI scans.29

Glatiramer generally is well tolerated and is not associated with influenza-like symptoms.30 Immediate postinjection reactions include local inflammation and an uncommon idiosyncratic reaction consisting of flushing, chest tightness with palpitations, anxiety, or dyspnea, which resolves spontaneously without sequelae. Routine laboratory monitoring is not considered necessary in patients treated with glatiramer, and the development of binding antibodies does not interfere with therapeutic efficacy.31

Mitoxantrone

A phase-III, randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial32 found that mitoxantrone, an anthracenedione antineoplastic agent, reduced the number of treated MS relapses by 67 percent and slowed progression on the Expanded Disability Status Scale, Ambulation Index, and MRI measures of disease activity. Mitoxantrone is recommended for use in patients with worsening forms of MS.

Acute side effects of mitoxantrone include nausea and alopecia. Because of cumulative cardiotoxicity, the drug can be used for only two to three years (or for a cumulative dose of 120 to 140 mg per m2). There also is some concern about treatment-related leukemia. Mitoxantrone is a chemotherapeutic agent that should be prescribed and administered only by experienced health care professionals.

NEW AND OTHER DRUGS

Natalizumab (Antegren) is in the final stages of phase-III clinical trails and is under accelerated review by the FDA. In a phase-II clinical trial,33 this drug appeared promising in that it reduced active MRI lesions by 90 percent and decreased MS relapses by more than 50 percent. Natalizumab is a monoclonal antibody that is directed against an adhesion molecule called VLA-4. The drug is administered intravenously once a month.

Despite lack of FDA approval and definitive evidence of efficacy, several other drugs commonly are used in patients with MS. A number of small clinical trials34–38 support the modest effect of intravenous IgG, azathioprine, methotrexate, and cyclophosphamide, either alone or in combination with standard therapy.

Initiation of Early Therapy

Accumulating evidence indicates that the best time to initiate disease-modifying treatment is early in the course of MS.39 Data indicate that irreversible axonal damage may occur early in relapsing-remitting MS,40 and that drug therapies appear to be more effective in preventing new lesion formation than in repairing old lesions. With disease progression, the autoimmune response of the disease may become more difficult to suppress. Both intramuscular interferon beta-1a therapy and subcutaneous interferon beta-1a therapy have been shown to reduce the cumulative probability of the development of clinically definite MS in patients who present with a first clinical demyelinating episode and have two or more brain lesions on an MRI scan.41,42 Based on these data, the National Multiple Sclerosis Society43 supports the initiation of immunomodulating therapy at the time of diagnosis.

The physician must weigh evidence and recommendations against the practical concerns of young patients for whom the prospect of starting therapy that requires self-injection may be frightening and burdensome. Furthermore, few long-term data (more than 10 years) are available on the safety and sustained efficacy of disease-modifying drugs. A patient may opt to defer therapy, hoping to be among the minority of persons with benign MS; however, certain MRI and clinical features should prompt the physician and patient to reconsider this approach.

An MRI scan with contrast-enhancing lesions, a large burden of white matter disease, or any T1 low-signal lesions (black holes) suggests a relatively poor prognosis.44 It may be useful to repeat brain MRI scanning in six months or one year to determine how quickly the disease process is evolving. The presence of spinal cord lesions or atrophy also suggests a poor prognosis. Clinical features may be less useful for assessing prognosis. Once definite disability develops, it may be too late to treat that component of the disease.

The ability to diagnose and treat MS has improved considerably in the past 10 years because of the availability of MRI and partially effective immunomodulating therapies. The limited efficacy of immunomodulating drugs in the later, noninflammatory stages of MS highlights the importance of developing remyelinating and neuroprotective strategies for the disease.