Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(2):173-183

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a demyelinating disorder of the central nervous system and the most common cause of nontraumatic neurologic disability in young adults. Types of MS include relapsing-remitting (most common), secondary progressive, and primary progressive. Clinically isolated syndrome and radiologically isolated syndrome are additional categories for patients with findings concerning for MS who do not yet meet the diagnostic criteria for the disease. Symptoms of MS depend on the areas of neuronal involvement. Common symptoms include sensory disturbances, motor weakness, impaired gait, incoordination, optic neuritis, and Lhermitte sign. A patient history, neurologic examination, and application of the 2017 McDonald Criteria are needed to diagnose MS accurately. Patients with MS should be treated by a multidisciplinary team that may include physical and occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, mental health professionals, pharmacists, dietitians, neurologists, and family physicians. Steroids are the mainstay of treatment for the initial presentation of MS and relapses. Patients who do not adequately respond to steroids may benefit from plasmapheresis. Patients with MS who smoke tobacco should be strongly encouraged to quit. Disease-modifying therapy has been shown to slow disease progression and disability; options include injectable agents, infusions, and oral medications targeting different sites in the inflammatory pathway. Symptom-based care is important to address the bowel and bladder dysfunction, depression, fatigue, movement disorders, and pain that often complicate MS.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a demyelinating disorder of the central nervous system and the most common cause of nontraumatic neurologic disability in young adults.1 Prevalence differs by latitude, with higher rates among those living further from the equator. The prevalence of MS is 40 per 100,000 people in Lubbock, Tex., compared with 191 per 100,000 people in Olmstead County, Minn.2 An estimated 1 million people in the United States live with MS.1 Risk factors include smoking and a history of infectious mononucleosis. Women are twice as likely as men to have MS, and there is a modest genetic influence.3,4

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| The 2017 McDonald Criteria should be used in the diagnosis of MS.25 | C | Clinical practice guideline |

| There is no difference in effectiveness between oral and intravenous steroids in treating acute relapses of MS.28,29 | A | Cochrane review and a separate systematic review and meta-analysis of good-quality clinical trials |

| Patients with MS who smoke tobacco should be encouraged to quit to decrease disability progression and development of secondary progressive MS.34,35 | B | Cohort study and cross-sectional study |

| Disease-modifying therapy should be initiated in patients with active MS.36,37 | A | Clinical practice guidelines supported by randomized controlled trials and systematic review and meta-analyses |

| Patients with MS benefit from a comprehensive program addressing overall wellness, symptom management, and comorbid mental health and physical conditions.38 | C | Clinical practice guideline |

A woman with MS diagnosed at 35 years of age has an average life expectancy of seven to eight years less than that of the general population. Because MS has a relatively high prevalence and patients have a long life span after diagnosis, many family physicians care for patients with the disease.5

Pathophysiology

Types of MS include relapsing-remitting (RRMS; most common), secondary progressive, and primary progressive (Table 16–13). There are also classifications for people with first episodes concerning for MS who do not meet the diagnostic criteria for MS (clinically isolated syndrome) and those with incidental radiologic findings concerning for MS in the absence of clinical symptoms (radiologically isolated syndrome).13

| Type | Disease course |

|---|---|

| Clinically isolated syndrome | First episode of symptoms characteristic of MS, with acute or subacute onset and lasting at least 24 hours; does not yet meet diagnostic criteria for MS; 80% of patients with clinically isolated syndrome and abnormal MRI findings progress to MS within 20 years compared with 20% of those with normal MRI findings |

| Radiologically isolated syndrome | Radiography shows evidence of inflammatory demyelination without clinical manifestations (i.e., incidental findings on radiography performed for other purposes); 30% to 40% of patients with radiologically isolated syndrome later meet criteria for clinically isolated syndrome or MS |

| Relapsing-remitting MS* | Episodes of acute neurologic dysfunction (relapses) followed by partial or complete improvement, with a stable clinical course between relapses; 85% of MS cases |

| Secondary progressive MS* | Progressive worsening of neurologic function following initial relapsing-remitting disease; acute exacerbations may occur during progressive phase; develops in 50% of patients with relapsing-remitting MS |

| Primary progressive MS* | Progressive worsening of neurologic function from onset of symptoms; acute exacerbations may also occur; 15% of MS cases |

MS is characterized by focal areas of inflammation, demyelination, gliosis (proliferation and activation of glial cells), and degeneration (axonal loss) secondary to immune-mediated attacks.10 There is debate about whether the inflammation leading to MS is initiated within or outside the central nervous system; however, T cells, B cells, macrophages (including central nervous system microglia), astrocytes, inflammatory mediators, and blood-brain barrier permeability are all involved in a response that is associated with myelin sheath destruction, axonal injury, and clinical symptoms.4,10,14–16 In RRMS, clinical lesions may resolve through mechanisms such as axonal changes, neuroplasticity, and remyelination.13 Progressive forms of MS are associated with cumulative axonal loss and increasing neurologic deficits.10

Clinical Presentation

Symptoms and signs of MS depend on the areas of neuronal involvement17 (Table 21,18–22). Common presenting symptoms include sensory disturbances, motor weakness, impaired gait, incoordination, optic neuritis (unilateral vision loss with pain worsened by extraocular movements), and Lhermitte sign (an electric shock–like sensation down the spine on neck flexion).18–20 Other symptoms include urinary, bowel, and sexual dysfunction.

| Cognitive dysfunction (e.g., learning, memory, processing speed) Decreased sensation (e.g., vibration, position, pain) Depressed mood Dysarthria Fatigue Focal sensory disturbances (e.g., numbness, tingling) Focal weakness Hearing loss or tinnitus Heat sensitivity | Lhermitte sign (an electric shock–like sensation down the spine on neck flexion) Motor disturbances (e.g., ataxia, imbalance, incoordination, tremor, weakness) Nystagmus Pain Sexual dysfunction (e.g., erectile dysfunction; problems with arousal, lubrication, pain, orgasm) Urinary or bowel disturbances Vertigo Visual disturbances (e.g., blurring, diplopia, optic neuritis) and defects |

Diagnosis

Multiple diseases may mimic MS clinically and radiologically (Table 3).13,18,23,24 The differential diagnosis includes genetic, infectious, inflammatory, metabolic, and neoplastic processes. Psychiatric diseases, ingestions, and nutritional deficiencies may also be mistaken for MS.13,18,23,24 Table 4 lists tests that may help differentiate MS from other diseases.18

| Disease category | Examples |

|---|---|

| Central and peripheral nervous system disease | |

| Degenerative diseases | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Huntington disease |

| Demyelinating disorders | Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (Guillain-Barré syndrome), chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, neuromyelitis optica, paraneoplastic syndromes |

| Structural lesions | Arnold-Chiari malformation, arteriovenous malformation, compressive spinal cord lesions, neoplasm |

| Vascular lesions | Cerebrovascular accident, CADASIL, hypertensive disease, migraine, vasculitis |

| Endocrine disorders | Hypothyroidism |

| Genetic disorders | Leukodystrophy, mitochondrial disease |

| Infections | HIV infection, Lyme disease, neurosyphilis, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy |

| Inflammatory and infiltrative disorders | Behçet syndrome, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome, Susac syndrome |

| Medications and illicit substances | Alcohol, anticholinergic drugs, cocaine, etanercept (Enbrel), infliximab (Remicade), isoniazid, methanol, phenytoin (Dilantin) |

| Nutritional | Manganese toxicity, vitamin B12 deficiency |

| Psychiatric disease | Anxiety disorders, conversion disorder, somatization |

| Test | Conditions | Test | Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Performed routinely Antinuclear antibody titers Borrelia titers Complete blood count Erythrocyte sedimentation rate Rapid plasma reagin Thyroid-stimulating hormone level Vitamin B12 level | Systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatologic disease Lyme disease Infection, inflammation, neoplasm Infection, inflammation Syphilis Hypothyroidism Vitamin B12 deficiency | Performed when indicated Angiotensin-converting enzyme level Autoantibody assays (e.g., antineutrophil cytoplasmic, anticardiolipin, antiphospholipid, Sjögren [anti–SS-A and anti–SS-B] antibodies) HIV screening Human T-lymphotropic virus I screening Very long-chain fatty acid levels | Sarcoidosis Behçet syndrome, Sjögren syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, vasculitis HIV infection T-cell leukemia Adrenoleukodystrophy |

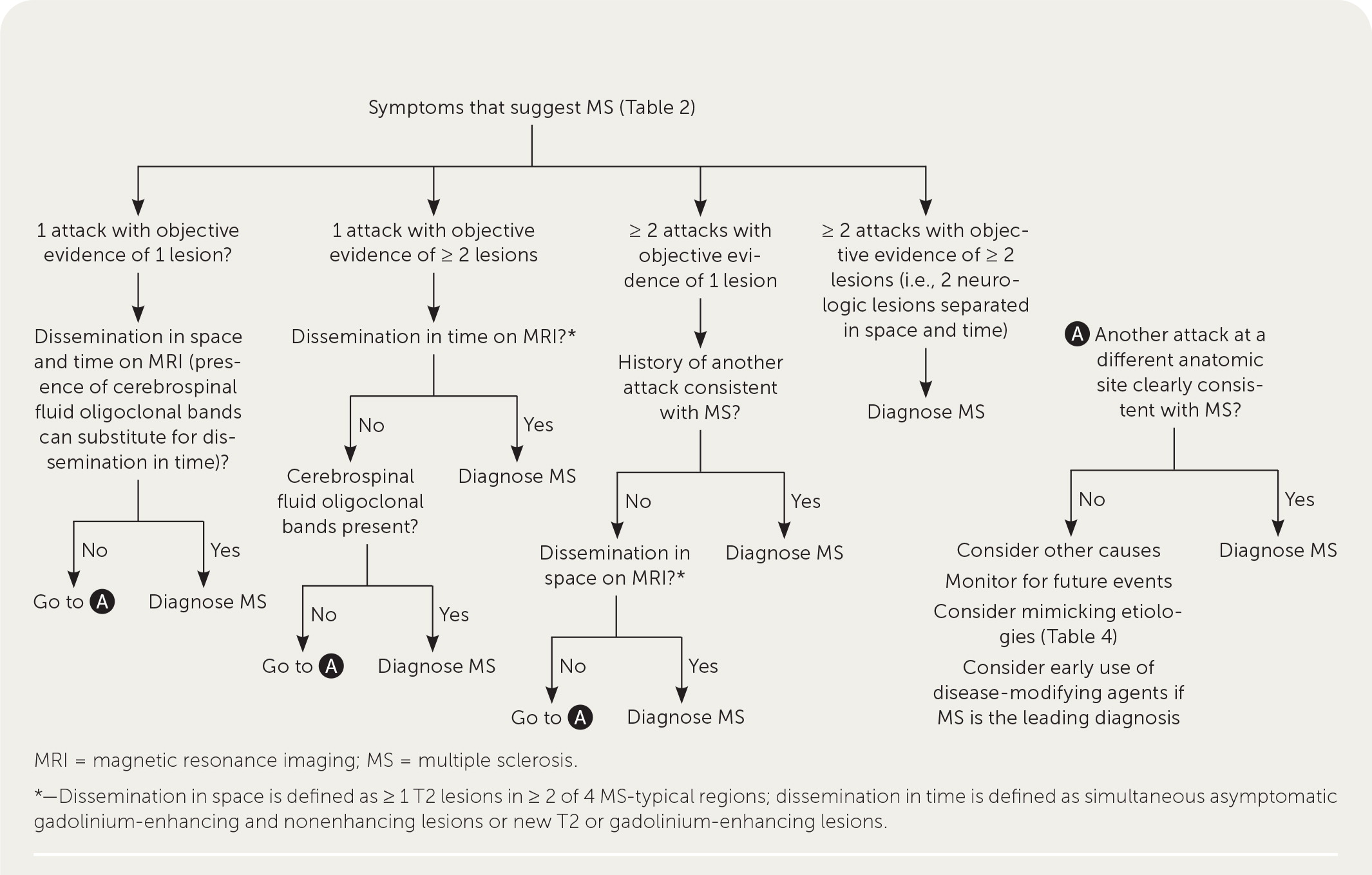

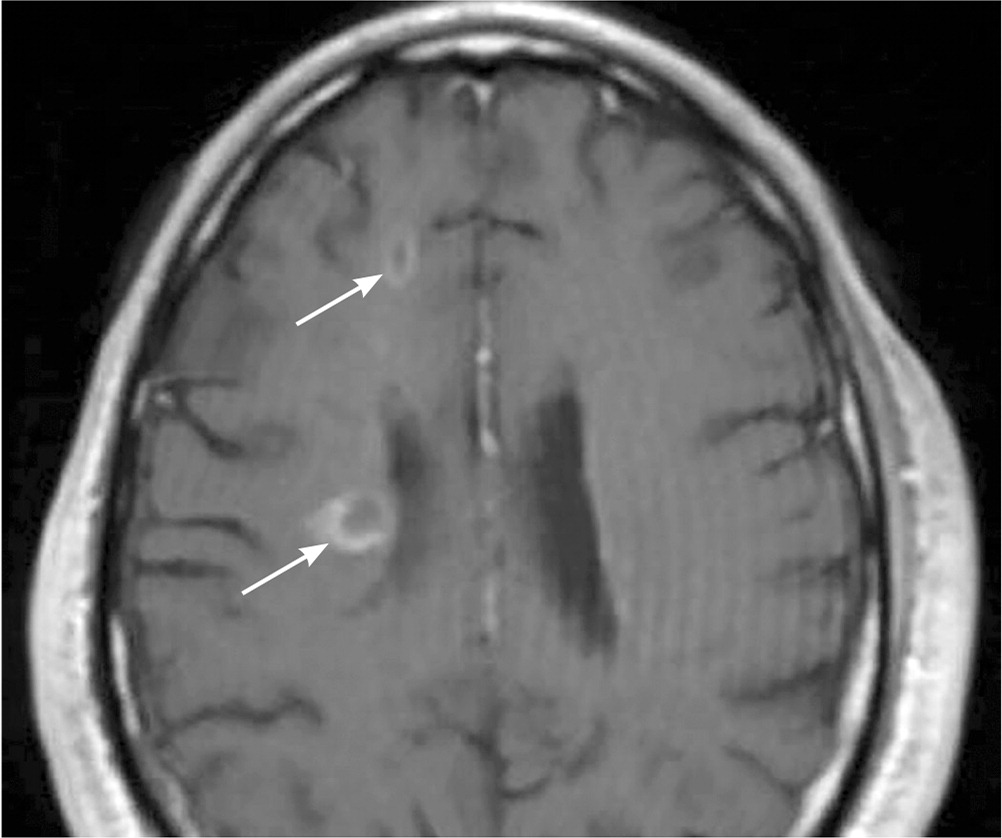

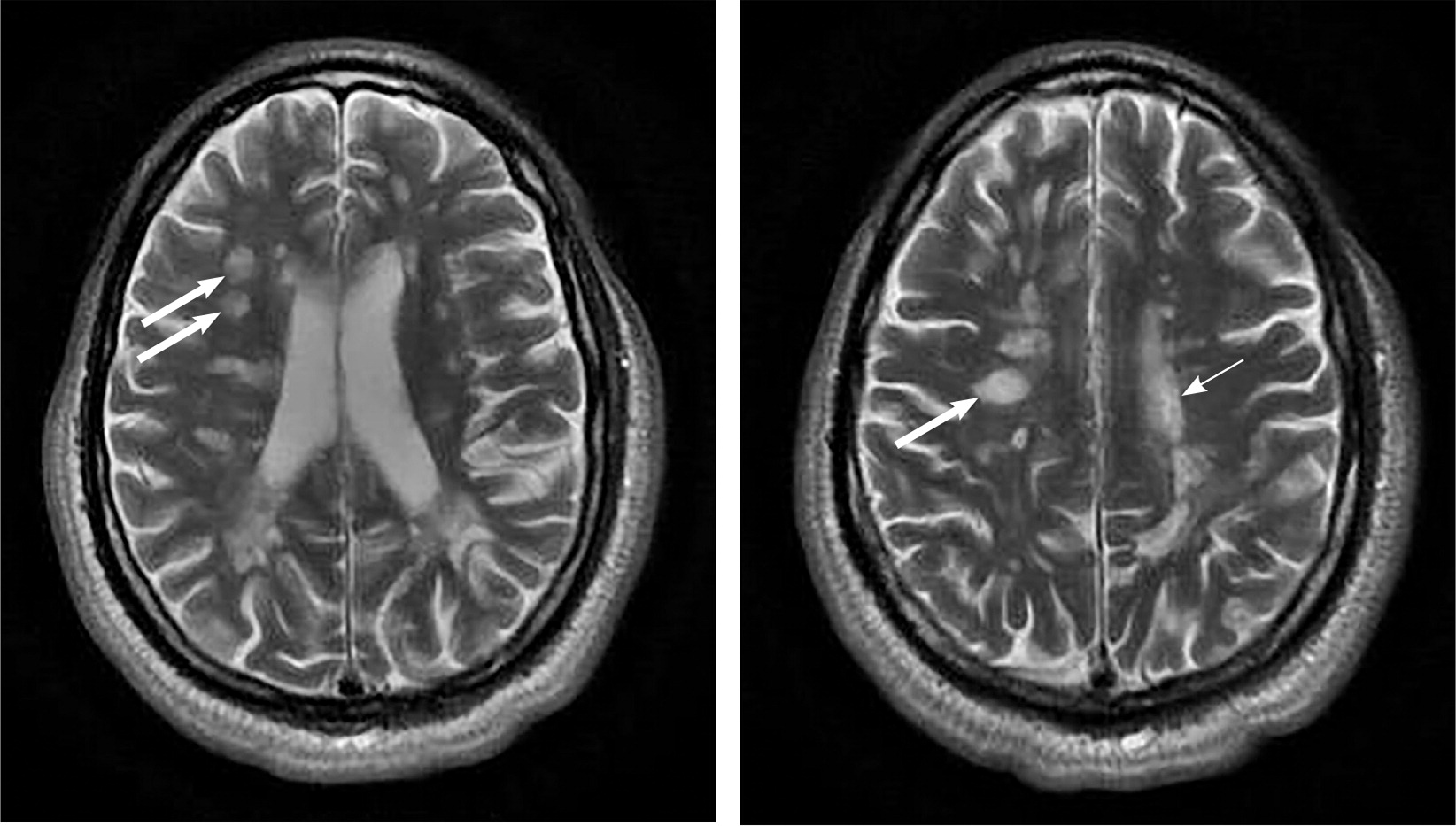

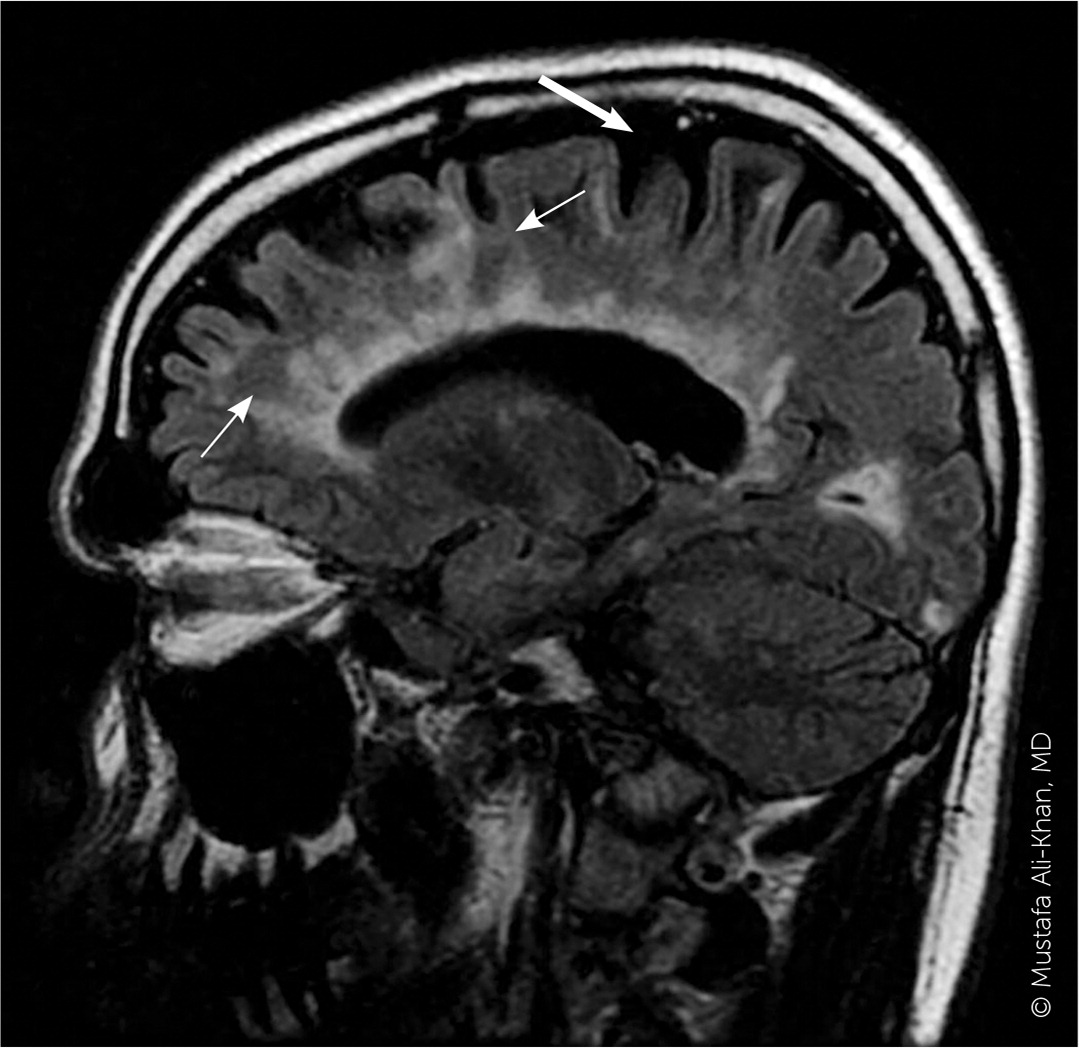

A patient history, neurologic examination, and application of the 2017 McDonald Criteria are needed to accurately diagnose MS (Table 5).25 Diagnosis relies on the acute exacerbations of MS being disseminated in space and time (Figure 118). In cases where only part of the diagnostic criteria are met, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and spine may be used to confirm the presence of lesions consistent with MS (Figure 2, Figure 3, and Figure 4).18 Cerebrospinal fluid assays demonstrating oligoclonal bands may also aid in meeting diagnostic criteria.25

| Number of lesions with objective clinical evidence | Additional data needed for a diagnosis of multiple sclerosis | |

|---|---|---|

| ≥ 2 clinical attacks | ≥ 2 | None* |

| ≥ 2 clinical attacks | 1 (as well as clear-cut historical evidence of a previous attack involving a lesion in a distinct anatomical location)† | None* |

| ≥ 2 clinical attacks | 1 | Dissemination in space demonstrated by an additional clinical attack implicating a different CNS site or by MRI |

| 1 clinical attack | ≥ 2 | Dissemination in time demonstrated by an additional clinical attack or by MRI OR demonstration of CSF-specific oligoclonal bands‡ |

| 1 clinical attack | 1 | Dissemination in space demonstrated by an additional clinical attack implicating a different CNS site or by MRI AND Dissemination in time demonstrated by an additional clinical attack or by MRI OR demonstration of CSF-specific oligoclonal bands‡ |

The diagnosis should be questioned if the patient has a family history of neurologic disorders other than MS, an abrupt or transient (less than 24 hours) presentation, progressive ataxia, cognitive dysfunction, other organ involvement, or nonspecific neurologic symptoms that are difficult to localize.13,20,26

Treatment

Patients with MS should be treated by a multidisciplinary team that may include physical and occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, mental health professionals, pharmacists, dietitians, neurologists, and family physicians.27

INITIAL PRESENTATION AND ACUTE RELAPSES

Steroids are the mainstay of treatment for the initial presentation of MS and MS relapses. A Cochrane review and another systematic review and meta-analysis found no difference in effectiveness between intravenous and oral steroids for relapse recovery or MRI activity.28,29 A higher dosage of steroids, such as 1,000 mg per day of methylprednisolone (intravenously or orally) for three days, is recommended.30,31 Patients who do not have an adequate response to treatment with steroids may benefit from plasmapheresis.30,32 A randomized controlled trial involving six plasmapheresis treatments in patients unresponsive to steroids found higher rates of complete recovery at one month than in those treated with placebo.33

SMOKING CESSATION

Patients with MS who smoke tobacco should be strongly encouraged to quit. A cohort study found that each smoke-free year was associated with a decrease in disability progression.34 A cross-sectional study found that each additional year of smoking accelerated the development of secondary progressive MS by 4.7% (95% CI, 2.3 to 7.2).35

DISEASE-MODIFYING THERAPY

In patients with active MS, long-term disease-modifying therapy should be initiated to decrease new clinical attacks and radiographic lesions and delay disability progression.36,37 There is disagreement about whether to use disease-modifying therapy in patients with clinically isolated syndrome.36–38

Interferon beta-1b (Betaseron, Extavia) was the first disease-modifying therapy approved for use in 1993. Since then, multiple injectable agents, infusions, and oral medications such as monoclonal antibodies and other immunomodulatory medications targeting multiple steps in the MS inflammatory pathway have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (Table 6).13,37–39

| Medication | Dosage and route | Selected adverse effects | Cost* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alemtuzumab (Lemtrada) | 12 mg per day for five days, IV; 12 months later, 12 mg once per day for three days, IV | Infusion reaction, increased risk of infection, thyroid problems, blood clots, immune thrombocytopenia, kidney problems | — (only available at specialty pharmacy) |

| Cladribine (Mavenclad) | 1.75 mg per kg twice yearly, orally | Increased risk of infection, headache, tuberculosis, malignancy, PML | — (only available at specialty pharmacy) |

| Dimethyl fumarate | 240 mg twice per day, orally | Flushing, gastrointestinal symptoms, PML | $130 (—) |

| Diroximel fumarate (Vumerity) | 231 mg twice per day, orally | Flushing, gastrointestinal symptoms, PML | — (only available at specialty pharmacy) |

| Fingolimod (Gilenya) | 0.5 mg once per day, orally | Arrhythmia, hepatic dysfunction, increased risk of infection, PML | — ($10,000) |

| Glatiramer (Copaxone, Glatopa) | 20 mg per mL once per day, subcutaneously 40 mg per mL three times per week, subcutaneously | Injection site reactions | 20 mg: $4,700 ($26,600, $4,700) 40 mg: $6,000 ($22,000, $5,000) |

| Interferon beta-1a (Avonex, Rebif) | 30 mcg once per week, intramuscularly 22 mcg or 44 mcg three times per week, subcutaneously | Influenza-like symptoms, injection site reactions, rare liver toxicity | 30 mcg: — ($7,200) 22 mcg or 44 mcg: — ($35,000) |

| Interferon beta-1b (Betaseron, Extavia) | 0.25 mg once every other day, subcutaneously | Influenza-like symptoms, injection site reactions, rare liver toxicity | — ($125,300, $6,500) |

| Mitoxantrone | 12 mg per m2 every three months, IV | Heart failure, increased risk of infection, leukemia | Only available at specialty pharmacy (—) |

| Monomethyl fumarate (Bafiertam) | 190 mg twice per day, orally | Flushing, gastrointestinal symptoms, PML | — (only available at specialty pharmacy) |

| Natalizumab (Tysabri) | 300 mg every four weeks, IV | Dizziness, nausea, rash, increased risk of infection, PML | — (only available at specialty pharmacy |

| Ocrelizumab (Ocrevus) | 600 mg every six months, IV | Infusion reactions, herpes, increased risk of malignancy | — (only available at specialty pharmacy) |

| Ofatumumab (Kesimpta) | 20 mg at weeks 0, 1, and 2, then 20 mg per month starting at week 4, subcutaneously | Liver injury, PML, increased risk of infections | — (only available at specialty pharmacy) |

| Ozanimod (Zeposia) | 0.92 mg once per day, orally | Arrhythmia, increased risk of infection, hepatic dysfunction, PML | — (only available at specialty pharmacy) |

| Peginterferon beta-1a (Plegridy) | 125 mcg every two weeks, subcutaneously | Influenza-like symptoms, injection site reactions, rare liver toxicity | — (only available at specialty pharmacy) |

| Ponesimod (Ponvory) | 20 mg once per day, orally | Arrhythmia, increased risk of infection, hepatic dysfunction, PML | — ($8,300) |

| Siponimod (Mayzent) | 2 mg once per day, orally | Arrhythmia, increased risk of infection, hepatic dysfunction, PML | — ($8,900) |

| Teriflunomide (Aubagio) | 7 mg or 14 mg once per day, orally | Nausea, diarrhea, rash, teratogenic | — (only available at specialty pharmacy) |

The choice of initial disease-modifying therapy is dependent on patient preference, disease activity, potential adverse effects, and specialist input. All approved agents help prevent disease progression, with a relative risk of progression from 0.47 for mitoxantrone to 0.87 for interferon beta-1a (Avonex, Rebif).40 For patients with less active disease, agents with a lower risk of adverse effects (e.g., cardiac arrhythmia, increased risk of malignancy, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy) are preferred at the cost of effectiveness. For patients with more active disease, effectiveness may be considered more important than avoiding adverse effects. Shared decision-making conversations should consider the availability of the medication options, route and frequency of administration, patient preferences regarding effectiveness vs. adverse effects, and the patient's ability to tolerate and comply with monitoring regimens.36,37

For patients who have newly diagnosed RRMS with minimal symptoms and MRI burden of disease, an appropriate regimen may include a moderately effective agent such as interferon or glatiramer (Copaxone, Glatopa) to control disease activity while minimizing adverse effects. In patients with newly diagnosed, rapidly evolving RRMS, a highly effective agent such as alemtuzumab (Lemtrada), cladribine (Mavenclad), natalizumab (Tysabri), or ocrelizumab (Ocrevus) may be considered. A greater risk of debilitating adverse effects is weighed against a greater chance of controlling disease activity in this strategy.38 Ocrelizumab is the only disease-modifying therapy currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for primary progressive MS.39

Medications should be continued for at least six months to allow time for benefits to occur. If the disease is not controlled by initial therapy, the patient should be offered a more effective medication, recognizing the increased potential for adverse effects.37,38 It is appropriate to consider switching medications if adverse effects develop.37

Once started, disease-modifying therapy is generally continued for the patient's lifetime; however, guidelines allow for exceptions. Discontinuation can be considered for patients with secondar y progressive MS who have a higher level of disability, are nonambulatory, and have not had a relapse in two years. Discontinuation can also be considered before conception for patients who want to become pregnant and have well-controlled MS.37,38 During pregnancy, patients tend to have a lower risk of flare-ups, with overall better-controlled disease.41

In addition to disease-modifying therapy, preliminary research suggests that hematopoietic stem cell transplantation may be a more effective alternative in preventing relapses and disability accumulation.42

SYMPTOM-BASED CARE

In addition to treatment directed at acute relapses and disease progression, patients with MS require a comprehensive program that addresses overall wellness, symptom management, and comorbid mental health and physical conditions (Table 7).13,22,38,43–85 A multidisciplinary approach is most effective for many symptoms. Physical activity has good evidence for improving walking ability (increased distance on six-minute walking test, faster times on 10-minute walking test), balance (as measured by the Berg Balance Scale), and depression (decreased scores on depression scales).43–45 Pharmacotherapy used for symptoms associated with MS is often off-label and supported by low-quality evidence. A notable exception is dalfampridine extended-release (Ampyra), which has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to improve walking in patients with MS.86 Pain is treated with analgesics, neuromodulators, hydrotherapy, and sometimes cannabinoids.49,82,84

| Symptom | Pharmacologic | Nonpharmacologic |

|---|---|---|

| Bladder dysfunction | Detrusor spasm: imipramine, muscarinics, detrusor muscle onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox) injections Nocturia: intranasal desmopressin Outlet disorder: alpha adrenergic blockers, cannabinoids | Detrusor spasm: avoidance of spicy or acidic foods, caffeine, and alcohol; bladder training; sacral neuromodulation Outlet disorder: catheterization |

| Bowel dysfunction | Constipation: bisacodyl (Dulcolax), docusate sodium (Colace), enemas, lubiprostone (Amitiza), magnesium oxide, polyethylene glycol (Miralax), psyllium (Metamucil) | Abdominal massage, biofeedback, bowel timing (planning toileting times), electrostimulation of abdominal muscles, transanal irrigation |

| Cognitive impairment | Donepezil (Aricept) Amantadine, ginkgo, and rivastigmine (Exelon) were found to have no clear benefit | Neuropsychological rehabilitation, occupational therapy |

| Depression and emotional lability | Bupropion (Wellbutrin), duloxetine (Cymbalta), escitalopram (Lexapro), fluoxetine (Prozac), sertraline (Zoloft), venlafaxine | Cognitive behavior therapy, multidisciplinary rehabilitation, physical activity |

| Fatigue | Amantadine, dextroamphetamine, methylphenidate (Ritalin), modafinil (Provigil), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (fluoxetine) | Aerobic exercise; avoidance of heat, overexertion, and stress; cognitive behavior therapy; mindfulness training |

| Movement disorders | Ataxia: baclofen (Lioresal), cannabinoids, dantrolene (Dantrium), threonine, tizanidine (Zanaflex) Impaired ambulation: dalfampridine extended-release (Ampyra) Tremor: onabotulinumtoxinA for focal tremors, beta blockers, diazepam (Valium), isoniazid | Ataxia: deep brain stimulation, vestibular rehabilitation Impaired ambulation: behavior change therapy, physiotherapy, supervised resistance training programs |

| Pain | Neuropathic pain First-line: amitriptyline, duloxetine, gabapentin (Neurontin), nortriptyline (Pamelor), pregabalin (Lyrica) Second-line: capsaicin cream, venlafaxine Trigeminal neuralgia First-line: carbamazepine (Tegretol), oxcarbazepine (Trileptal) Second-line: baclofen, gabapentin, lamotrigine (Lamictal), pregabalin Musculoskeletal pain: analgesics, baclofen | Hydrotherapy, physiotherapy, surgical procedures for trigeminal neuralgia |

| Sexual dysfunction | Female: duloxetine Male First-line: phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors Second-line: intercavernous vasodilators | Female: clitoral vibratory stimulation, vaginal lubrication Male: penile prostheses, vacuum appliances |

| Spasticity | Benzodiazepines, cannabinoids, dantrolene, gabapentin, intrathecal or oral baclofen, onabotulinumtoxinA, tizanidine | Electromagnetic therapy, physiotherapy, structured exercise program, transcranial magnetic stimulation, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, whole body vibration |

| Vision problems (oscillopsia) | First-line: gabapentin Second-line: memantine (Namenda) | Vestibular rehabilitation |

Prognosis

More than one-half of patients with untreated RRMS transition to secondary progressive disease.36 Greater disability and brain atrophy at the time of diagnosis, male sex, and older age are risk factors for progression to more significant functional limitations.13 Disease-modifying therapy has been shown to alter the course of MS, decreasing the rate at which disability progresses, and is also associated with a lower likelihood of transitioning to progressive disease.37,87

Many governments, nonprofit organizations, and websites provide information and support for individuals and families affected by MS (eTable A).

| Resource | Website |

|---|---|

| Multiple Sclerosis Association of America | https://mymsaa.org |

| Multiple Sclerosis Foundation | https://www.msfocus.org |

| Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada | https://mssociety.ca |

| National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke | https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Multiple-Sclerosis-Information-Page |

| National Multiple Sclerosis Society | https://www.nationalmssociety.org |

| Patients Like Me | https://www.patientslikeme.com/join/ms |

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Saguil, et al.,18 and Calabresi.88

Data Sources: PubMed, the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Essential Evidence Plus, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (UK), and the European Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis were searched for relevant articles and clinical practice guidelines. Key words included multiple sclerosis, demyelinating disorders, disease-modifying treatment, and others as directed by the search. Search dates: August 2021 and May 2022.

Editor's Note: Dr. Saguil is a contributing editor for AFP.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the U.S. Army or the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences.