This is a corrected version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 2005;72(2):287-291

Patient information: See related handout on foreign body ingestion in children, written by the author of this article.

Author disclosure: Nothing to disclose.

Because many patients who have swallowed foreign bodies are asymptomatic, physicians must maintain a high index of suspicion. The majority of ingested foreign bodies pass spontaneously, but serious complications, such as bowel perforation and obstruction, can occur. Foreign bodies lodged in the esophagus should be removed endoscopically, but some small, blunt objects may be pulled out using a Foley catheter or pushed into the stomach using a bougienage. [ corrected] Once they are past the esophagus, large or sharp foreign bodies should be removed if reachable by endoscope. Small, smooth objects and all objects that have passed the duodenal sweep should be managed conservatively by radiographic surveillance and inspection of stool. Endoscopic or surgical intervention is indicated if significant symptoms develop or if the object fails to progress through the gastrointestinal tract.

Foreign body ingestion is a potentially serious problem that peaks in children aged six months to three years. It causes serious morbidity in less than one percent of all patients, and approximately 1,500 deaths per year are attributed to ingestion of foreign bodies in the United States.1,2 In 1999, the American Association of Poison Control documented 182,105 incidents of foreign body ingestion by patients younger than 20 years.1,2

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Emergent endoscopy is recommended for patients with button batteries or sharp objects in the esophagus. | C | 4 |

| Observation is recommended for patients with small, blunt objects below the diaphragm or with asymptomatic objects beyond the reach of an endoscope. | C | 2,4 |

| Surgical removal should be considered for blunt objects beyond the stomach that remain in the same location for longer than one week. | C | 4 |

Clinical Features

An estimated 40 percent of foreign body ingestions in children are not witnessed, and in many cases, the child never develops symptoms.2 A retrospective review3 found that 50 percent of children with confirmed foreign body ingestions were asymptomatic. Objects that have passed the esophagus generally do not cause symptoms unless complications, such as bowel perforation or obstruction, occur. Patients with objects lodged in the esophagus may be asymptomatic or may present with symptoms varying from vomiting or refractory wheezing to generalized irritability and behavioral disturbances (Table 1).1,2,4 Longstanding esophageal foreign bodies may cause failure to thrive or recurrent aspiration pneumonia. Esophageal perforation may result in neck swelling, crepitations, and pneumomediastinum. If perforation occurs in the stomach or intestines, fever and abdominal pain and tenderness may develop. Bowel obstruction by a foreign body may cause abdominal distension, pain, and tenderness. Common sites for obstruction by an ingested foreign body include the cricopharyngeal area, middle one third of the esophagus, lower esophageal sphincter, pylorus, and ileocecal valve.1,2,4

| Blood in saliva |

| Coughing |

| Drooling |

| Dysphagia/odynophagia |

| Failure to thrive |

| Fever |

| Food refusal |

| Foreign body sensation in throat |

| Gagging |

| Irritability |

| Pain in neck, throat, or chest |

| Recurrent aspiration pneumonia |

| Respiratory distress |

| Stridor |

| Tachypnea or dyspnea |

| Vomiting |

| Wheezing |

Once they are beyond the esophagus, most sharp objects pass without complication, even though there is an increased risk of complications. Potential complications include bowel obstruction, perforation, and erosion into adjacent organs. Patients may develop abdominal pain and tenderness, nausea, vomiting, fever, hematochezia, or melena. Radiographic studies may show free air or a dilated bowel.1,2,4

Identification of Ingested Foreign Bodies

Plain radiographs generally are used in the initial investigation of patients with suspected foreign body ingestion, but in one study3 of 325 children, only 64 percent of the ingested objects were radiopaque. Most foreign bodies pass through the gastrointestinal tract spontaneously. In the pre-endoscopy era, 93 to 99 percent of blunt objects passed without intervention, and approximately one percent required surgical removal.1 Today, 10 to 20 percent of children who ingest foreign bodies are managed with endoscopy.1

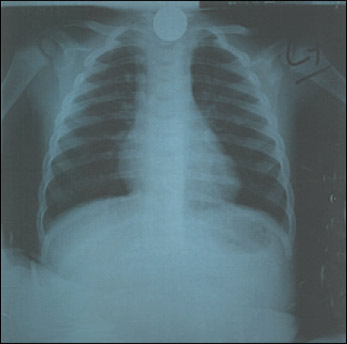

Small, smooth objects usually pass into the stomach but occasionally may become lodged in the esophagus. As few as one half of esophageal foreign bodies cause symptoms, and physicians must maintain a high index of suspicion for foreign body ingestion.1,5 Biplane radiographs of the neck, chest, and upper abdomen are indicated for all patients suspected of having swallowed a foreign body. Metal detectors can identify ingested metal objects but offer little added benefit over plain radiographs. Most foreign bodies are radiopaque, but wooden, plastic, and glass objects, as well as fish and chicken bones, may not be seen on radiographs.1

Some experts recommend barium esophagography for patients with a suspected radiolucent foreign body lodged in the esophagus.1 Because contrast studies pose a risk of aspiration and compromise subsequent endoscopy, an expert panel4 recommended endoscopy rather than barium study if radiographs are negative. Computed tomographic scans, ultrasonography, and magnetic resonance imaging also have been used to identify radiolucent foreign bodies.2,4

Management of Ingested Foreign Bodies

OBJECTS IN THE ESOPHAGUS

Referral for endoscopic removal is indicated if a child with a suspected esophageal foreign body and negative radiographs presents to a facility where pediatric endoscopy is available. In facilities without endoscopic capabilities, barium esophagography should be considered only after consultation with a gastroenterologist. In patients who have swallowed a sharp, radiolucent object, such as a fish bone, direct laryngoscopy should be performed; endoscopy should be performed if laryngoscopy is negative and symptoms persist.6

Button batteries and sharp objects lodged in the esophagus require urgent endoscopic removal; all other foreign bodies lodged in the esophagus should be removed or advanced into the stomach.1 The traditional use of glucagon to advance foreign bodies into the stomach has not been proved effective.8,9 Most blunt objects in the esophagus may be observed for up to 24 hours. If the object fails to pass into the stomach, it should be removed or possibly pushed into the stomach. Objects that have been lodged in the esophagus for more than 24 hours or for an unknown duration should be removed endoscopically.4 If the object has been lodged in the esophagus for more than two weeks, there is significant risk of erosion into surrounding structures, and surgical consultation should be obtained before attempting removal.1,4

Coins are the most common objects ingested by children in the United States2 (Figure 3). The Foley and bougienage techniques have been proposed to remove coins and similar smooth objects from the esophagus. Because endoscopy generally is the preferred and accepted method of removing coins from the esophagus, strict criteria should be used when considering other methods. A single coin must have been lodged in the esophagus for less than 24 hours in a child with no history of esophageal abnormalities, no respiratory distress, and no prior foreign body ingestion.10 In the Foley technique, a Foley catheter is passed beyond the coin and the balloon is inflated with radiocontrast dye, then pulled out under fluoroscopy. This technique has a high success rate if performed by an experienced operator, but the potential for airway compromise has prevented it from becoming universally accepted.

Bougienage seems to be safe, is less costly than endoscopic removal,11 and does not require anesthesia. The goal is to push the coin into the stomach, where it should pass spontaneously. In some patients, however, pushing the coin into the stomach may result in obstruction requiring endoscopic or surgical exploration.

OBJECTS DISTAL TO THE ESOPHAGUS

Although up to 90 percent of foreign bodies that have passed the esophagus will pass spontaneously, an expert panel4 recommended that sharp objects be removed endoscopically before they have passed beyond the duodenal curve because they are more likely to cause complications or require surgical removal. Sharp objects that cannot be removed endoscopically should be followed with daily radiographs, and surgical removal should be considered if the object does not progress in three days.4 Large objects that have not traveled beyond the duodenal curve should be considered for endoscopic removal because of the increased risk of obstruction and complications. Some experts recommend endoscopic removal of items larger than 2 cm (0.79 inches) in diameter or longer than 3 cm (1.18 inches) in infants.1 In children one year of age and older, objects longer than 3 to 5 cm (1.18 to 1.97 inches) may not pass, and consultation is advised to consider endoscopic removal.2

Patients with small, blunt objects lodged distal to the esophagus, or with any asymptomatic object beyond the reach of the endoscope should be observed. Most objects will pass within four to six days of ingestion, but some may take up to four weeks. Patients who have swallowed blunt, radiopaque objects should be followed with weekly radiography, and parents should be instructed to watch for the passage of the object in stool. Any foreign body that has not passed the stomach in three to four weeks should be removed endoscopically. Blunt objects beyond the stomach that remain in the same location for more than one week should be considered for surgical removal.4 Any foreign body that causes fever, vomiting, abdominal pain, or significant symptoms should be considered for emergency removal.2,4

Because two thirds of parents fail to identify the object in their child’s stool when it is passed, some experts recommend contrast radiographs if a radiolucent foreign body is not seen in the stool two weeks after its ingestion.3 Contrast studies may not be necessary in an asymptomatic child who has swallowed a low-risk radiolucent foreign body such as a plastic bead.

BUTTON BATTERIES

Early intervention is indicated for patients who have swallowed button or disc batteries because of the potential for voltage burns and direct corrosive effects. Burns can occur as early as four hours after ingestion.1 Button batteries that remain in the stomach for more than 48 hours or that are larger than 2 cm in diameter should be removed endoscopically. Once they are past the duodenal sweep, 85 percent of button batteries pass in less than 72 hours.4 Radiographs should be obtained every three to four days to follow the progress of the battery until it has been passed.4