Am Fam Physician. 2017;95(1):22-28

Patient information: See related handout on esophageal cancer, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Esophageal cancer has a poor prognosis and high mortality rate, with an estimated 16,910 new cases and 15,910 deaths projected in 2016 in the United States. Squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma account for more than 95% of esophageal cancers. Squamous cell carcinoma is more common in nonindustrialized countries, and important risk factors include smoking, alcohol use, and achalasia. Adenocarcinoma is the predominant esophageal cancer in developed nations, and important risk factors include chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease, obesity, and smoking. Dysphagia alone or with unintentional weight loss is the most common presenting symptom, although esophageal cancer is often asymptomatic in early stages. Physicians should have a low threshold for evaluation with endoscopy if any symptoms are present. If cancer is confirmed, integrated positron emission tomography and computed tomography should be used for initial staging. If no distant metastases are found, endoscopic ultrasonography should be performed to determine tumor depth and evaluate for nodal involvement. Localized tumors can be treated with endoscopic mucosal resection, whereas regional tumors are treated with esophagectomy, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, chemoradiotherapy, or a combination of modalities. Nonresectable tumors or tumors with distant metastases are treated with palliative interventions. Specific prevention strategies have not been proven, and there are no recommendations for esophageal cancer screening.

Esophageal cancer is the eighth most common cancer worldwide. Nearly four out of five cases occur in nonindustrialized nations, with the highest rates in Asia and Africa.1,2 The National Cancer Institute estimates that in 2016, there will be 16,910 new cases and 15,910 deaths from esophageal cancer in the United States.3

Esophageal cancer is associated with a poor prognosis. Despite advances in diagnosis and treatment, the overall five-year survival rate for persons with esophageal cancer is 15% to 20% worldwide and in the United States.4

WHAT IS NEW ON THIS TOPIC: ESOPHAGEAL CANCER

In a cohort study of 11,028 patients with low- and high-grade dysplasia Barrett esophagus, the overall incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma was 0.12% per year.

Antireflux surgery appears to have minimal benefit in preventing esophageal cancer.

A Cochrane review of 53 studies evaluating palliation for dysphagia showed that self-expanding metal stents are safe, effective, and provide quicker relief than brachytherapy, radiotherapy, esophageal bypass surgery, and chemotherapy.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Upper endoscopy should be the initial diagnostic procedure in patients with symptoms suggestive of esophageal cancer. Biopsy of suspicious lesions should be performed. | C | 20, 21 |

| Integrated positron emission tomography/computed tomography and endoscopic ultrasonography should be used for comprehensive staging of esophageal cancer. | C | 28–30 |

| Endoscopic mucosal resection should be considered the first-line therapy for mucosal-based stage 0 or T1a tumors. | C | 22, 31 |

The two main subtypes of esophageal cancer are squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. These subtypes account for more than 95% of malignant esophageal tumors. Rare subtypes of esophageal cancer, which are not discussed in this article, include lymphomas, melanomas, carcinoid tumors, and sarcomas.5

Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Esophagus

Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common subtype of esophageal cancer outside of the United States, accounting for 90% of cases worldwide.6 The highest rates occur in China, Central Asia, and East and South Africa.2 The incidence of squamous cell carcinoma in the United Sates is approximately three per 100,000 person-years.7 The incidence is consistent between sexes, is higher among blacks, and peaks from 60 to 70 years of age.8 Important risk factors for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma include smoking, alcohol use, and achalasia9,10 (Table 18–15 ).

| Squamous cell carcinoma |

| Age 60 to 70 years |

| Achalasia (10-fold risk) |

| Smoking (ninefold risk) |

| Alcohol use (three- to fivefold risk with ≥ three drinks per day) |

| Black race (threefold risk) |

| High-starch diet without fruits and vegetables |

| Adenocarcinoma |

| Age 50 to 60 years |

| Male sex (eightfold risk) |

| White race (fivefold risk) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease (five- to sevenfold risk, depending on frequency of symptoms) |

| Obesity (2.4-fold risk with body mass index > 30 kg per m2) |

| Smoking (twofold risk) |

| Barrett esophagus |

Esophageal Adenocarcinoma

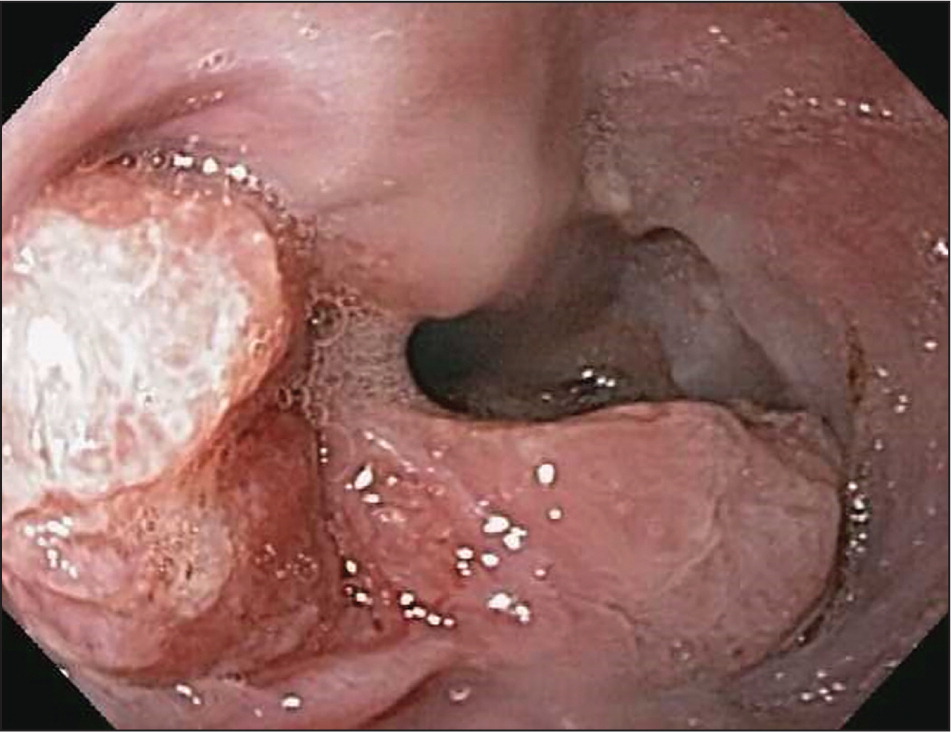

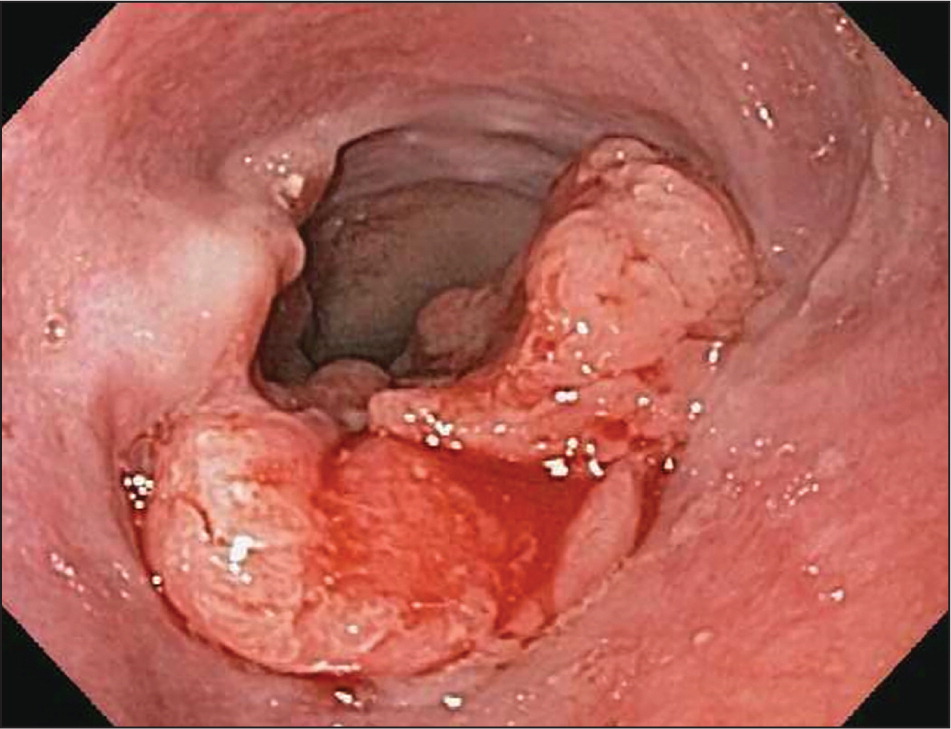

Esophageal adenocarcinoma is the predominant type of esophageal cancer in North America and Europe6 (Figure 1, Figure 2, and Figure 3). According to 2013 data from the National Cancer Institute, most cases occur in adults older than 50 years, and the incidence among persons 65 years and older is 11.8 to 16.3 per 100,000 person-years, with an eightfold higher risk in men compared with women and a fivefold higher risk in whites compared with blacks3 (Table 18–15 ).

Major risk factors for esophageal adenocarcinoma include gastroesophageal reflux disease, obesity, and smoking.12–14 Barrett esophagus is a known precursor disease to esophageal adenocarcinoma with a low rate of conversion. A cohort study of 11,028 patients with low- and high-grade dysplasia Barrett esophagus followed over a five-year period showed that the overall incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma was 0.12% per year.16

A 41% reduced risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma has been observed among persons with Helicobacter pylori infection.17 It is believed that gastric acid secretions that contribute to reflux disease and Barrett esophagus are reduced as a result of gastric mucosa atrophy caused by H. pylori.18 This association is still under investigation, and treatment of H. pylori infection continues to be recommended in accordance with American College of Gastroenterology guidelines.

Clinical Presentation

Esophageal cancer is often asymptomatic in the early stages. Patients with advanced disease may present with progressive dysphagia (solids first, followed by liquids as the disease progresses), unintentional weight loss (10% or more in the preceding three to six months), odynophagia (painful swallowing, often noticed initially with dry foods), new-onset dyspepsia, heartburn unresponsive to medication, chest pain, or signs of blood loss.

Of these symptoms, dysphagia alone or combined with unintentional weight loss is the most common presentation in patients with esophageal cancer. Uncommon findings include cervical adenopathy, hematemesis, hemoptysis, or hoarseness from recurrent nerve involvement, which is present in less than 10% of patients at the time of diagnosis.19

Diagnosis

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommend that patients with the clinical presentation described previously undergo upper endoscopy as the initial diagnostic evaluation to exclude esophageal cancer 20,21 (Figure 420–23 ). Other indications warranting endoscopy include persistent upper abdominal symptoms despite medical therapy and upper abdominal symptoms in patients older than 45 years.24

Chromoendoscopy (topical application of stains to improve visualization of different mucosal tissues) and narrow band imaging (use of blue and green light to improve visualization of blood vessels and other mucosal features) are often used during endoscopy to improve identification of suspicious lesions. Biopsies of suspicious lesions should be performed, but if esophageal stricture prevents adequate biopsies, brush cytology can also be used.25 Barium studies should be reserved for patients unable to undergo upper endoscopy.15

Staging

Staging usually involves multiple modalities in a stepwise approach and should be tailored to the patient as well as the experience of the clinicians and institution providing care.20 The diagnostic, staging, and treatment approach for patients with suspected esophageal cancer is outlined in Figure 4.20–23

STAGING CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM

Accurate staging is important to establish the best treatment options. The most recent edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer's Cancer Staging Manual released in 2010 continues to use the tumor-node-metastasis classification but also includes other prognostic variables.26 This edition incorporates a histologic grade (G) criteria and has a separate staging group for each type of esophageal cancer (Table 2).26

| Primary tumor (T) |

| Tis: high-grade dysplasia |

| T1a: tumor invades lamina propria |

| T1b: tumor invades submucosa |

| T2: tumor invades muscularis propria |

| T3: tumor invades adventitia |

| T4a: tumor invades nearby structures (resectable)* |

| T4b: tumor invades nearby structures (unresectable)† |

| Regional lymph nodes (N) |

| N0: no regional lymph node metastases |

| N1: 1 to 2 positive regional lymph nodes |

| N2: 3 to 6 positive regional lymph nodes |

| N3: ≥ 7 positive regional lymph nodes |

| Distant metastasis (M) |

| M0: no distant metastases |

| M1: distant metastases |

| Histologic grade (G) |

| G1: well differentiated |

| G2: moderately differentiated |

| G3: poorly differentiated |

| G4: undifferentiated |

LABORATORY TESTS

After the diagnosis is confirmed with endoscopic biopsies, additional laboratory studies may be helpful in evaluating the tumor stage. The NCCN recommends evaluating for anemia with a complete blood count, which will influence therapy if the patient requires chemotherapy. The NCCN also recommends checking for elevated hepatic transaminase or alkaline phosphatase levels, which suggest liver or bone metastases, respectively.21

The use of serum tumor markers (i.e., antibodies to tumor-associated antigens) is under investigation and is not currently recommended for decision making in patients with local or regional disease.20 However, patients with documented or suspected metastatic esophageal junction cancer may be candidates for trastuzumab (Herceptin) therapy and should be assessed for HER2/neu overexpression.21

POSITRON EMISSION AND COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY

Positron emission tomography (PET) and computed tomography (CT) have specific roles in providing important staging information. CT is more sensitive than PET for evaluating local-regional lesions.27 Chest and abdominal CT with intravenous and oral contrast media should be ordered as the initial tests to evaluate mediastinal involvement, lung parenchyma, and liver metastasis. PET, however, is superior to CT for detecting distant metastatic sites.27 Both studies together (integrated PET/CT) have a sensitivity of 69% to 78% and a specificity of 82% to 88% for detecting all metastases.28

ENDOSCOPIC ULTRASONOGRAPHY

If there are no distant metastases, endoscopic ultrasonography should be performed to determine the tumor depth of invasion and nodal involvement, which are both useful in providing prognostic information and guiding treatment options.29 The sensitivity and specificity of endoscopic ultrasonography for determining invasion range from 82% to 87% compared with 73% to 78% for standard endoscopy with narrow band imaging.30

In experienced centers, fine-needle aspiration of adjacent lymph nodes can be performed during the endoscopic ultrasonography.22 In addition, endoscopic mucosal resection of noncircumferential lesions smaller than 2 cm in diameter can provide prognostic information for staging and is potentially curative.21,22,31

OTHER STAGING PROCEDURES

Additional staging options for more advanced local-regional disease include laparoscopy and thoracoscopy.

Treatment

There are many treatment options for squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus depending on the stage at diagnosis. Curative surgical therapy, chemotherapy, and chemoradiotherapy have all been shown to increase survival and improve the health-related quality of life for patients (Table 33,22,26,31 ).

| SEER stage | AJCC stage | Treatment | Five-year survival rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Localized | Stage I (T1, N0, M0) through stage IIB (T3, N0, M0) | Endoscopic mucosal resection | 41% |

| Esophagectomy if invasion beyond the submucosa without lymph node involvement | |||

| Regional | Stage IIB (T1-2, N1, M0) through stage IIIC (any T classification, N3, M0) | Esophagectomy with lymphadenectomy | 23% |

| Neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy | |||

| Distant | Stage IV | Brachytherapy | 5% |

| Esophageal bypass surgery | |||

| Jejunostomy or gastrostomy tubes | |||

| Palliative chemotherapy | |||

| Self-expanding mucosal stents | |||

| Trastuzumab (Herceptin) therapy |

LOCALIZED TUMORS

Mucosal-based tumors are limited to the mucosa (stage 0) or may invade the lamina propria without lymph node or distant involvement (stage I). The risk of lymphatic spread in these tumors is less than 2%, and endoscopic mucosal resection is the treatment of choice, especially for noncircumferential tumors less than 2 cm in diameter.22,31 Endoscopic mucosal resection successfully removes 91% to 98% of T1a cancers.32

REGIONAL TUMORS

For patients with potentially curable localized tumors (stage IIA/IIB), surgical resection via esophagectomy is the primary treatment. The optimal approach (thoracic vs. transhiatal) and technique (open vs. minimally invasive) have yet to be determined; randomized trials are needed to clarify outcomes in terms of survival and health-related quality of life. Currently, the risk of serious postoperative complications for all approaches and techniques is 30% to 50%, and in-hospital mortality is about 5%. Possible complications include anastomotic strictures and leaks causing pulmonary morbidities, recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, gastric outlet obstruction (esophagectomy with gastric reconstruction), and chylothorax.34 Outcomes appear to depend on the experience and volume of the surgeon and health care facility; for this reason, esophagectomies are increasingly performed at a few high-volume specialty centers.22,35

Advanced regional disease (stage III) often requires a more aggressive approach with perioperative chemotherapy. Neoadjuvant (before surgery) chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy compared with esophagectomy alone has shown a two-year survival benefit of 5.1% with neoadjuvant chemotherapy (number needed to treat = 19) and 8.7% with chemoradiotherapy (number needed to treat = 11).36 Neoadjuvant chemotherapy and chemoradiotherapy are especially beneficial in adenocarcinoma.22 Adjuvant (after surgery) chemotherapy may be beneficial for patients with squamous cell carcinoma. For patients who experience residual or recurrent disease after complete resection, there is no good evidence for or against the use of chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy. Occasionally, chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy is used without surgery in patients who have resectable disease but are poor surgical candidates.29 The five-year survival rate for regional disease is 23%.3

DISTANT TUMORS

For those with stage IV esophageal cancer or whose disease is nonresectable, palliative strategies include chemotherapy, esophageal stents, brachytherapy (local radiotherapy), surgical placement of jejunostomy or gastrostomy tubes, and esophageal bypass surgery.

A Cochrane review of 53 studies evaluating various options of palliation for dysphagia showed that self-expanding metal stents are safe, effective, and provide quicker relief than brachytherapy, radiotherapy, esophageal bypass surgery, and chemotherapy.37 Self-expanding metal stents are recommended over other modalities and are often used in conjunction with brachytherapy and radiotherapy to reduce risk of reintervention.

Chemotherapy seems to offer greater benefit in squamous cell carcinoma than in adenocarcinoma; however, it may prolong life by only a few months.22

Trastuzumab in combination with other chemotherapies (except anthracyclines) has also been shown to extend survival by a few months in patients with HER2/neu gene overexpression.38

Prevention and Screening

Some studies have shown a decreased risk of esophageal cancer with the use of proton pump inhibitors,39 aspirin or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs,40 and statins.41 Other studies, however, have not shown benefit. No recommendations exist to support use of these medications for the sole purpose of cancer prevention. Antireflux surgery also appears to have minimal benefit in preventing esophageal cancer.42 Antioxidants and mineral supplements have not been shown to decrease the risk of gastrointestinal cancers, including esophageal cancers.22,43 Attempts to reduce the risk factors of obesity and smoking have not been rigorously evaluated in the setting of esophageal cancer prevention. Nonetheless, primary care physicians should make lifestyle recommendations on the basis of promoting overall health.

There are no recommendations for screening for esophageal cancer in the general population. Cancer surveillance guidelines exist for patients known to have Barrett esophagus.23

Data Sources: A Pub Med search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms Barrett esophagus, esophageal carcinoma, and esophageal neoplasm. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, control trials, and reviews. Searches were also performed using Clinical Rules, the Cochrane database, Essential Evidence Plus, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines, and DynaMed. Search dates: May 3, 2015, and September 16, 2016.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.