Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(7):420

My father couldn't swallow. There I was, in a Florida hospital room, alone with an 87-year-old father who couldn't swallow. I am the oldest sibling of five. Our mother had died four years earlier, but our father stayed on in their little ranch house. He had hung a hand-scrawled sign on the front door—“Hard of hearing. Come on in!”—which I begged him to take down, considering there had been burglaries nearby. He continued to drive to church despite experiencing mini-strokes. I called him every night during those years. He'd say things like, “I'm standing at the kitchen counter, but my legs won't support me.” I wanted to help him, but I lived several states away.

He had worked two jobs most of his life, yet he still found time to teach me things like how to replace a generator in a 1956 Pontiac station wagon in the dead of winter.

But now, I sat at his hospital bedside. He had been admitted for pneumonia and worsening heart failure, and then had a transient ischemic attack (TIA) in the midst of it. It was a no-win situation: the treatment for one disease would exacerbate the other. Then, the swallowing problem developed. Nothing was to be done—except place a feeding tube.

Hoping he would understand through the haze of illness, I told him that his only option for getting out of the hospital was a feeding tube. “Not afraid to die,” he said. But my siblings believed that the TIA was affecting his ability to reason and thought he should reconsider. “Why are you against a feeding tube?” they asked when I phoned each of them.

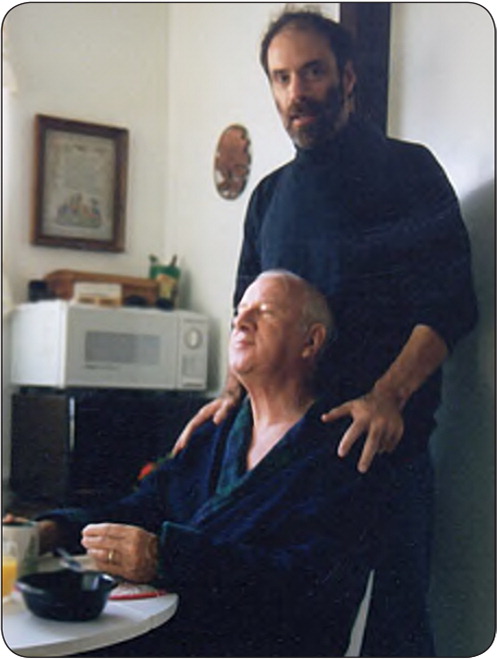

There we were; just the two of us. Instead of leaning over the Pontiac on a wintry day, cussing up a storm, replacing a broken part, he lay quietly. And this broken part, his ability to swallow, couldn't be fixed. He had supported me unquestioningly during the most difficult days of my life. Should I now support him unquestioningly by doing something that my brothers and sister weren't so sure about? Should I take him at his word? I thought about the way he taught me to use a double-headed axe, how to change a tire, how he had trusted me to solder copper pipes in our house when the heating system failed while he was away at work. He had always trusted me. I didn't have to think twice about that.

I signed the order declining a feeding tube.—Terry Lee

Commentary

As a palliative care specialist, I often discuss dysphagia at the end of life with patients and families. Many families feel deeply driven to provide their loved ones sustenance, even when clinicians advise that a feeding tube will not benefit them. It may be hard for patients to accept the limited benefits of artificial feeding. Multiple studies have shown that feeding tubes do not extend a dying patient's longevity at the end of life. When my stepfather faced this decision with his siblings, he considered his father's expressed wishes in the context of the trust that was the bedrock of their relationship. I often reflect on his experience—what a gift it is to make caring, difficult choices on behalf of loved ones at the end of life.

Resources

For Patients

Dunn H. Hard Choices for Loving People, 6th ed. Naples, Fla.: Quality of Life Publishing Co.; 2016

For Physicians

Pollens R. Role of the speech-language pathologist in palliative hospice care. J Palliat Med. 2004;7(5):694-702

Grant MD, Rudberg MA, Broday JA. Gastrostomy placement and mortality among hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 1998;279(24):1973-1976

Borum ML, Lynn J, Zhong Z, et al. The effect of nutritional supplementation on survival in seriously ill hospitalized adults: an evaluation of the SUPPORT data. Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48(5 suppl): S33-S38