Am Fam Physician. 2020;102(12):732-739

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Peripheral neuropathy, a common neurologic problem encountered by family physicians, can be classified clinically by the anatomic pattern of presenting symptoms and, if indicated, by results of electrodiagnostic studies for axonal and demyelinating disease. The prevalence of peripheral neuropathy in the general population ranges from 1% to 7%, with higher rates among those older than 50 years. Common identifiable causes include diabetes mellitus, nerve compression or injury, alcohol use, toxin exposure, hereditary diseases, and nutritional deficiencies. Peripheral neuropathy is idiopathic in 25% to 46% of cases. Diagnosis requires a comprehensive history, physical examination, and judicious laboratory testing. Early peripheral neuropathy may present as sensory alterations that are often progressive, including sensory loss, numbness, pain, or burning sensations in a “stocking and glove” distribution of the extremities. Later stages may involve proximal numbness, distal weakness, or atrophy. Physical examination should include a comprehensive neurologic and musculoskeletal evaluation. If the peripheral nervous system is identified as the likely source of the patient's symptoms, evaluation for potential underlying etiologies should initially focus on treatable causes. Initial laboratory evaluation includes a complete blood count; a comprehensive metabolic profile; fasting blood glucose, vitamin B12, and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels; and serum protein electrophoresis with immunofixation. If the initial evaluation is inconclusive, referral to a neurologist for additional testing (e.g., electrodiagnostic studies, specific antibody assays, nerve biopsy) should be considered. Treatment of peripheral neuropathy focuses on managing the underlying etiology. Several classes of medications, including gabapentinoids and antidepressants, can help alleviate neuropathic pain.

Peripheral neuropathy is one of the most common neurologic problems encountered by family physicians.1,2 Peripheral neuropathy can be classified clinically by the anatomic pattern of presenting symptoms and, if indicated, by results of electrodiagnostic studies for axonal and demyelinating disease.2,3 Peripheral nerves consist of motor, sensory, and autonomic nerve fibers. It is important to differentiate peripheral neuropathy from other disorders with similar presentations and to identify and address potential causes.

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not order a magnetic resonance imaging scan of the spine or brain for patients with only peripheral neuropathy (without signs or symptoms suggesting a brain or spine disorder). | American Association of Neuromuscular and Electrodiagnostic Medicine |

Epidemiology

The prevalence of peripheral neuropathy in the general population ranges from 1% to 7%, with higher rates among those older than 50 years.4,5 The most common identifiable causes of peripheral neuropathy include diabetes mellitus, nerve compression or injury, alcohol use, toxin exposure, hereditary diseases, and nutritional deficiencies.

Evaluation

The pathophysiology of peripheral neuropathy results from injury to small- or large-diameter nerve fibers. Damage can occur to the cell body, axon, myelin sheath, or a combination of these, leading to symptoms such as numbness, tingling, pain, and weakness.3,10 Large nerve fibers mediate motor, sensory, vibration, and proprioception functions. Small nerve fibers mediate pain, temperature, and autonomic functions.1

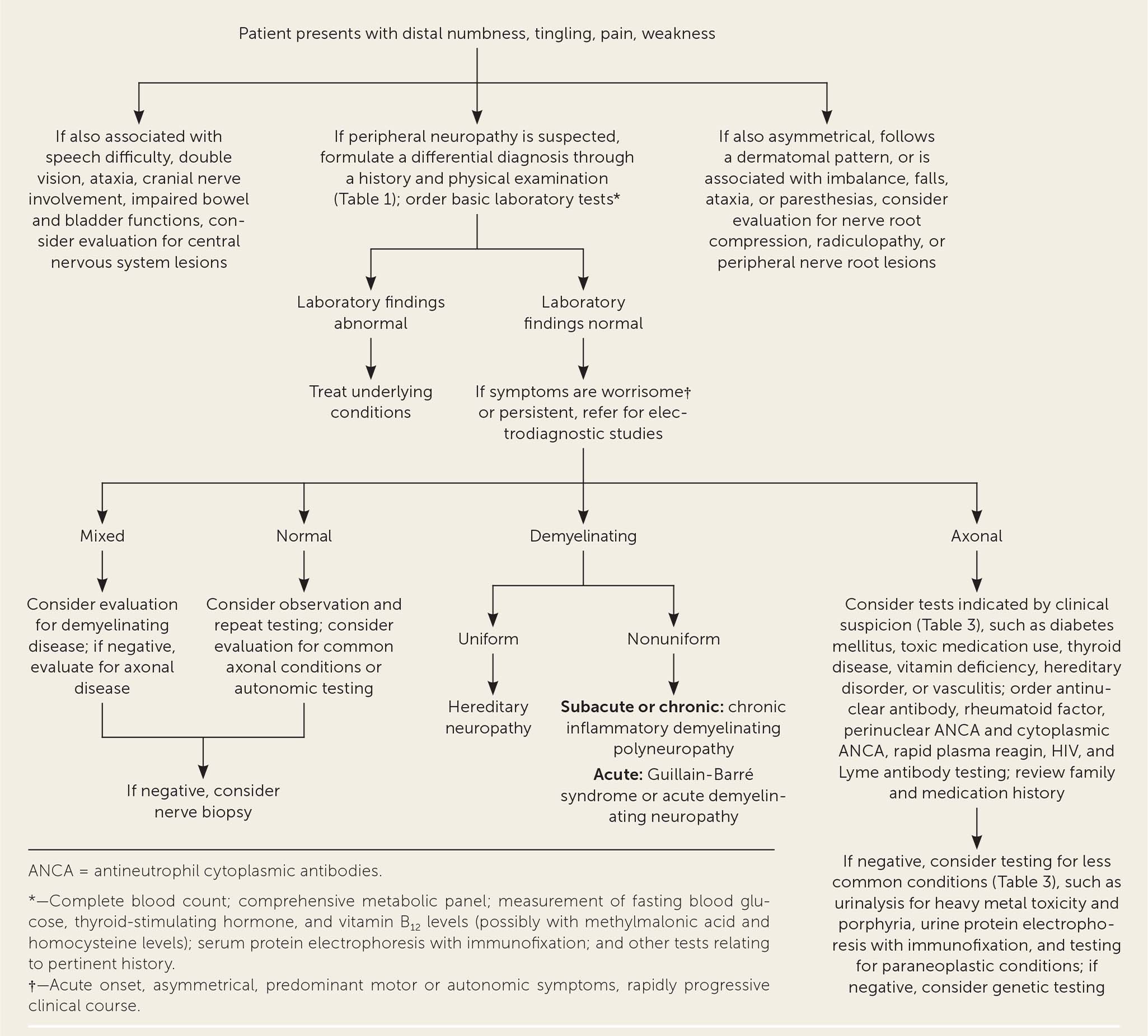

A systematic approach should be used to evaluate and manage patients with symptoms of peripheral neuropathy (Figure 1).11 Distinguishing peripheral neuropathy from central nervous system (CNS) and other pathology is an important first step. CNS lesions should be suspected in patients with speech disturbance, ataxia, visual disturbance, cranial nerve involvement, or bowel and bladder incontinence. Evaluation for nerve compression, radiculopathy, or peripheral nerve root lesions should be considered in patients with symptoms that are asymmetrical; follow a dermatomal pattern; or are associated with numbness, imbalance, falls, ataxia, and paresthesias.

If peripheral neuropathy is suspected, a differential diagnosis should be formulated through a history and physical examination.12 The anatomic distribution of peripheral neuropathy symptoms can be categorized as focal, multifocal, or symmetrical (Table 113). Symmetrical peripheral neuropathy can be further classified as distal or proximal. Less common patterns of peripheral neuropathy involve the cranial nerves, autonomic nerves, and nerves of the upper extremities.

| Focal | |||

| Acromegaly Amyloidosis Direct trauma to nerves, such as repeated minor trauma, traction, injection, cold exposure, burns, radiation Entrapment/compressive neuropathies | Ischemic lesions Leprosy Myxedema Neoplastic infiltration Rheumatoid arthritis Sarcoidosis | ||

| Symptoms | |||

| Sensory and motor symptoms | |||

| Predominantly sensory symptoms, including pain and paresthesias | |||

| In severe or chronic cases, motor symptoms may include weakness and atrophy | |||

| Multifocal | |||

| Connective tissue diseases | Infections (HIV/AIDS) | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | Leprosy | ||

| Hereditary predisposition to pressure palsies | Vasculitis | ||

| Symptoms | |||

| Sensory and motor symptoms are asymmetrical and affect multiple areas of the body | |||

| Sensory symptoms include pain, paresthesias, vibration, and proprioception | |||

| Motor symptoms may include weakness and atrophy | |||

| Autonomic symptoms may be present | |||

| Symmetrical distal sensorimotor | |||

| Acromegaly Alcohol use Amyloidosis Celiac disease Chronic kidney disease Connective tissue diseases Cryoglobulinemia Diabetes Gouty neuropathy Hypothyroidism/hyperthyroidism Infections (HIV/AIDS, Lyme disease) Inherited diseases (Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, familial amyloidosis) | Liver disease Malignancy Medication induced (see Table 2) Nutritional deficiencies (vitamins B6, B12, and E; thiamine; folate; copper; phosphate) Postgastrectomy syndrome Toxin exposure (heavy metals, carbon monoxide, acrylamide, hexacarbons, ethylene oxide, glue) Vasculitis Whipple disease | ||

| Symptoms | |||

| Distal sensory and motor symptoms involve both sides symmetrically | |||

| Sensory symptoms include pain, paresthesias, vibration, and proprioception | |||

| Motor symptoms may include weakness and atrophy | |||

| Autonomic symptoms may be present | |||

| Symmetrical proximal motor | |||

| Acute arsenic poisoning Chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy Diabetes Guillain-Barré syndrome Hypothyroidism | Infections (HIV/AIDS, Lyme disease, diphtheria) Malignancies Porphyria Vincristine exposure | ||

| Symptoms | |||

| Motor symptoms include weakness and atrophy of proximal muscles in a symmetrical anatomic distribution | |||

| Less common patterns | |||

| Neuropathies with cranial nerve involvement | |||

| Diabetes Guillain-Barré syndrome Infections (HIV/AIDS, Lyme disease, diphtheria) | Neoplastic invasion of the skull base or meninges Sarcoidosis | ||

| Symptoms | |||

| Sensory and motor symptoms involve the cranial nerves, such as problems with speech, swallowing, taste, and sensory or autonomic functions; coughing; head, pharyngeal, or neck pain; and weakness of the trapezius, sternocleidomastoid, or tongue muscles | |||

| Neuropathies predominant in upper extremities | |||

| Diabetes Guillain-Barré syndrome Hereditary amyloid neuropathy type II Hereditary motor sensory neuropathy | Lead toxicity Porphyria Vitamin B12 deficiency | ||

| Symptoms | |||

| Sensory and motor symptoms predominantly involve the upper limbs | |||

| Sensory symptoms include pain, paresthesias, vibration, and proprioception | |||

| Motor symptoms may include weakness and atrophy | |||

| Neuropathies with autonomic involvement | |||

| Amyloidosis | Paraneoplastic neuropathy | ||

| Diabetes | Porphyria | ||

| Lymphoma | Thallium, arsenic, or mercury toxicity | ||

| Symptoms | |||

| Autonomic symptoms may include orthostatic intolerance, gastroparesis, bowel and bladder changes, erectile dysfunction, and blurry vision | |||

History

A detailed history of symptoms is essential. Symptom onset and timing may be most helpful in narrowing the differential diagnosis. Location and distribution help distinguish focal, multifocal, and symmetrical patterns. Aggravating and remitting factors can be clues to exogenous causes, and a complete review of systems should be performed to evaluate for autonomic and vasomotor symptoms.

Early peripheral neuropathy may present as sensory alterations that are often progressive, including sensory loss, numbness, pain, or burning sensations in a “stocking and glove” distribution of the extremities.3 Later stages may involve proximal numbness, distal weakness, or atrophy.3 One-third of patients with peripheral neuropathy have neuropathic pain.1 Other common presenting symptoms include a stabbing or electric shock sensation, allodynia, hyperalgesia, and hyperesthesia.1,4,13,14 Patients may also report autonomic symptoms such as orthostatic intolerance, gastroparesis, changes in bowel and bladder function, erectile dysfunction, and blurry vision, or vasomotor symptoms such as dryness of the eyes, mouth, or skin, and burning or flushing.1

The history should also include toxin and medication exposures (Table 2); illnesses that can cause neuropathy, such as Lyme disease or HIV; trauma; family history of neurologic diseases or skeletal deformities; and recent travel.3,10,15 Recent travel could reveal compressive neuropathies or exposure to toxins or infections. Because vaccination against diseases such as influenza, meningococcus, shingles, and rabies rarely causes Guillain-Barré syndrome and associated neuropathy, immunization status should be reviewed as part of a thorough history. A history of childhood clumsiness, high arches, or difficulty with shoe fitting may suggest a hereditary neuropathy.1 These inherited diseases warrant specialist referral.16

| Antiepileptic drugs Lithium Phenytoin (Dilantin) Antimicrobial/antiviral drugs Chloroquine Dapsone Didanosine Ethambutol Interferon alfa Isoniazid Metronidazole (Flagyl) Nitrofurantoin Stavudine Triazoles Cardiovascular drugs Amiodarone Hydralazine Procainamide Statins | Chemotherapy agents Bortezomib (Velcade) Cisplatin Epothilones Oxaliplatin Paclitaxel Thalidomide Vincristine Other drugs Amitriptyline Cimetidine Colchicine Disulfiram (Antabuse) Levodopa Misoprostol (Cytotec) Nitrous oxide Pyridoxine Suramin Tumor necrosis factor alpha inhibitors | Metals Arsenic Gold Lead Mercury Thallium Solvents Acrylamide Carbon disulfide Carbon monoxide 2,4-dichlorophenoxy-acetic acid Ethylene oxide Glue Hexacarbons Organophosphorus esters |

A review of systems can identify weight loss associated with infections or malignancies, swallowing dysfunction, dysautonomia suggesting CNS involvement, skin and joint changes suggesting rheumatoid arthritis or other autoimmune disease, anemia consistent with conditions such as chronic kidney disease or vitamin B12 deficiency, and symptoms of an underlying endocrinopathy or an autoimmune process.10,16

Mimickers of peripheral neuropathy should also be considered. These include upper motor neuron diseases, myelopathies, syringomyelia, dorsal column disorders such as tabes dorsalis, and psychogenic symptoms.13

The onset and timing of a neuropathy can provide diagnostic clues. Toxin exposures may have fulminant symptoms that progress more rapidly than other causes. Medication-induced peripheral neuropathy generally presents in a chronic pattern over weeks to months.17 Neuropathic symptoms associated with trauma or ischemic infarction are usually acute and most severe at the onset of the event. Other possible causes of acute symptom onset include vasculitis, autoimmune disorders, or cryoglobulinemia.1,18 Inflammatory and metabolic neuropathies are typically subacute or chronic with symptoms progressing over weeks to months.3

Physical Examination

The physical examination should include a comprehensive neurologic examination, testing of the cranial nerves, fundoscopy, assessment for muscle fasciculations (often evident in the tongue), and evaluation of muscle bulk and tone.1 An underlying systemic illness should be considered if there are new changes in breathing or cardiac function, rashes or skin lesions, or lymphadenopathy.10 Asymmetry and nonanatomic distribution warrant consideration of psychogenic etiologies or less common diagnoses, including vasculitis, myxedema, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, or neoplastic infiltration (Table 113). Signs of long-standing neuropathy such as calf atrophy, hammer toes, and pes cavus should prompt concern for hereditary neuropathies.1

Nerve compression or injury from trauma or medical procedures should be considered. Common areas of compression include the sciatic nerve, fibular nerve, and femoral cutaneous nerve.3 Common compression peripheral neuropathies include carpal tunnel syndrome, cubital tunnel syndrome, and radiculopathy from spinal degeneration.1

In up to 50% of cases, the cause of peripheral neuropathy may not be identified with a history and physical examination, especially if the symptoms are mild. Additional physical examination testing may be needed for certain high-risk patient populations, such as those with diabetes. Combining vibratory sensation testing with a 128-Hz tuning fork plus sensory testing with a 10-g Semmes-Weinstein monofilament increases the sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of peripheral neuropathy compared with either test alone in patients with diabetes.1,19 However, without risk factors or clinical symptoms of peripheral neuropathy, a positive monofilament test cannot confirm the diagnosis and other factors must be considered.19

Laboratory Testing

Initial testing in patients with suspected peripheral neuropathy should include a complete blood count; comprehensive metabolic profile; and fasting blood glucose, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and vitamin B12 levels.1,20 Patients with peripheral neuropathy have a high prevalence of monoclonal proteins; therefore, the American Academy of Neurology recommends routine serum protein electrophoresis with immunofixation in these patients.21

Guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology suggest that the highest-yield tests for identifiable symmetrical distal polyneuropathy include blood glucose level (elevated in 11% of patients), serum protein electrophoresis with immunofixation (findings are abnormal in 9% of patients), and vitamin B12 level (low in 3.6% of patients).21 Additional tests may be considered if indicated by history and physical examination findings (Table 311).

| Tests | Clinical disorders* |

|---|---|

| Routine | |

| Complete blood count; comprehensive metabolic panel; measurement of fasting blood glucose, thyroid-stimulating hormone, and vitamin B12 levels; serum protein electrophoresis with immunofixation | — |

| If indicated by clinical suspicion | |

| Ethanol, folate, thiamine, phosphorus levels | Alcohol use disorder, Whipple disease, postgastrectomy syndrome, gastric retention, vitamin deficiency |

| Glucose tolerance, A1C level | Diabetes mellitus |

| HIV antibody | HIV infection |

| Hepatic panel | Liver disorders |

| Lyme antibodies | Lyme disease |

| Rapid plasma reagin, Venereal Disease Research Laboratory | Syphilis |

| Urine protein electrophoresis with immunofixation | Demyelinating neuropathy |

| Urinalysis (including 24-hour urine collection) | Heavy metal toxicity, porphyrias, multiple myeloma |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme levels | Sarcoidosis |

| Antinuclear antibodies, perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies, cytoplasmic antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies | Vasculitis, connective tissue disorders |

| Testing for uncommon conditions, if indicated | |

| Paraneoplastic panel | Malignancy, carcinomatosis |

| Antimyelin-associated glycoprotein, antiganglioside antibodies | Sensorimotor neuropathy |

| Antisulfatide antibodies | Autoimmune polyneuropathy |

| Cryoglobulins | Cryoglobulinemia |

| Salivary flow rate, Schirmer test, rose bengal test, labial gland biopsy | Sjögren syndrome |

| Cerebrospinal fluid analysis | Guillain-Barré syndrome, acute or chronic inflammatory demyelinating neuropathy (nonuniform demyelination) |

| Genetic testing | Hereditary neuropathy (uniform demyelination) |

| Uric acid level | Gout |

| Arsenic, gold, lead, mercury, thallium levels | Heavy metal toxicity |

Electrodiagnostic Studies and Imaging

Peripheral neuropathy is likely if the history and physical examination reveal corresponding neuropathic findings. The diagnosis may be confirmed with electrodiagnostic studies, including nerve conduction tests and electromyography, although the value of such testing is debated.1

One retrospective study of patients with symmetrical distal polyneuropathy found that electrodiagnostic studies changed the diagnosis or management in only two of 368 patients.1,22 Studies also show that electrodiagnostic tests have low utility as part of initial workup.1,23 Given these findings, electrodiagnostic studies are not routinely indicated.

However, patients should be referred for electrodiagnostic studies if symptoms are worrisome (e.g., acute onset, asymmetrical, predominantly motor or autonomic symptoms, rapidly progressive clinical course) or if initial workup is normal and symptoms persist.1,20,22 If demyelinating conditions are suspected, electrodiagnostic studies can be confirmatory. Normal findings on electrodiagnostic studies significantly decrease the likelihood of peripheral neuropathy but are more accurate in the larger, axonal fibers. Treatment of the suspected diagnosis should be initiated while electrodiagnostic studies are pending so that care is not delayed.

Unlike with radiculopathy (sensation changes) or myelopathy (motor changes), imaging is often not required for suspected peripheral neuropathy.23 A systematic review did not show high sensitivity or specificity with magnetic resonance imaging and revealed significant heterogeneity among the studies.24 In cases of polyradiculopathy, plexopathy, or radiculoplexus neuropathy, magnetic resonance imaging may help in localizing an atypical neuropathy.25 Idiopathic peripheral neuropathy is the presumed diagnosis if electrodiagnostic studies performed in the setting of an unclear diagnosis show axonal, symmetrical neuropathy.26

Indications for Referral

Referral to a neurologist should be considered when initial laboratory testing, history, and physical examination findings are unrevealing. More urgent referral is indicated for acute, subacute, severe, or progressive symptoms to prevent a delay in treatment.19 Additionally, patients with polyradiculoneuropathy or multifocal neuropathy, as opposed to presentations that match anatomic distribution, may warrant specialist consultation.19 Pure motor or autonomic signs in the absence of sensory changes may signal a less common cause, and referral may be beneficial.19 In addition to skin and nerve biopsies, neurologists may perform additional serologic and procedural studies.14

Procedural Studies

Rarely, procedural studies such as autonomic testing and nerve biopsies may be necessary to aid in the diagnosis and management of peripheral neuropathy. Autonomic testing may be indicated because dysfunction is challenging to identify on examination. Skin biopsies may also be considered in patients with a burning sensation, numbness, and pain. Autonomic testing and skin biopsies capture small, unmyelinated nerve fibers and can be important to a neurologist looking for a specific pathology early in the course of a disease.

Nerve biopsy, usually of the sural nerve, may be considered to confirm a diagnosis before starting aggressive treatments or if the diagnosis is uncertain despite appropriate workup.27,28 In a recent study of older adults under the care of a neurologist, biopsies were classified as diagnostic in 24% of patients and as essential or helpful in 81% of patients.26 Nerve biopsies are most helpful in diagnosing vasculitis, leprosy, amyloidosis, leukodystrophy, sarcoidosis, and some chronic inflammatory demyelinating neuropathies.

Principles of Treatment

Treatment of peripheral neuropathy focuses on managing the underlying condition. In addition, treatment of the associated symptoms can significantly improve the patient's quality of life.

Nonpharmacologic strategies such as proper foot hygiene, wearing appropriate footwear, weight loss, and physical therapy and gait training can help improve symptoms in those with lower extremity peripheral neuropathy.1 Several oral medications help alleviate neuropathic pain.1,20,29,30 Gabapentinoids (gabapentin [Neurontin], pregabalin [Lyrica]) and antidepressants (amitriptyline, nortriptyline [Pamelor], venlafaxine, duloxetine [Cymbalta], bupropion [Wellbutrin]) appear to be moderately effective and are recommended as first-line options.29,30

Topical medications, including lidocaine and capsaicin, can be added as adjuvants to oral medications. Opioids are reserved as a last-line option and should not be used routinely because of limited effectiveness, long-term safety concerns, and abuse potential.

Data Sources: PubMed was searched using the terms peripheral neuropathy, diagnosis, evaluation, physical examination, and epidemiology. We excluded diabetic peripheral neuropathy and other terms that focused on one specific diagnosis or system. Results were from the preceding five years and published in English. References used in Essential Evidence Plus, DynaMed, and UpToDate were also reviewed. Search dates: July 19, 2019, and July 24, 2020.