Am Fam Physician. 2021;103(9):570-572

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Case Scenario #1

A 35-year-old patient, J.P., presented to my office with difficulty sleeping and anxiety about job performance. J.P. is a lawyer who started a position six months ago to assist unaccompanied minors seeking asylum. The patient has been feeling more anxious recently and worries that something might happen to the children in her family if she is not constantly watching them. J.P. has difficulty sleeping for more than three hours at a time and drinks as many as five cups of coffee during the day to combat low energy. I suspect that the patient's work might be causing these symptoms, but what is the best and most efficient way to confirm the source of J.P.'s stress?

Case Scenario #2

Earlier this year, my colleague, L.R., led an initiative at our clinic to integrate medication-assisted treatment for substance use disorder. L.R. often provides staff training sessions on this topic and incorporates stories of people who have experienced addiction and overdose as an educational tool. My colleague has recently been asking for last-minute coverage on their clinic days and has been increasingly delayed in closing charts. Staff have mentioned that L.R. has become uncharacteristically impatient and irritable. When they ask whether there is anything wrong, L.R. brushes off their concern, saying, “Everything is fine. My patients have it much worse than me.” What is the best way to approach my colleague about these changes in behavior?

Commentary

Many people, including health care professionals, law enforcement professionals, journalists, and lawyers, may encounter situations that result in secondhand exposure to trauma. Often, family physicians are vicariously exposed to the trauma of their patients as they share stories of domestic violence, war, gun violence, child abuse, homelessness, and life-changing diagnoses, including cancer and COVID-19. These clinical experiences can be compounded by other forms of witnessed trauma, including exposure to repeated violence portrayed in the news and social media. Chronic exposure to secondhand trauma can lead to vicarious trauma, whereby an individual internalizes the emotional experiences of others as though that individual had personally experienced them. Vicarious trauma can result in a change of worldview and disturb a person's sense of justness and safety of the world. See the Office for Victims of Crime toolkit1 for a glossary of terms related to vicarious trauma (https://ovc.ojp.gov/program/vtt/glossary-terms). Unaddressed vicarious trauma can compromise a physician's ability to provide care or professional services and can affect their own personal health and relationships.

Risk Factors and Symptoms

Vicarious trauma is part of a spectrum of responses to trauma exposure, including secondary traumatic stress, caregiver fatigue, compassion fatigue, and burnout. These conditions have varying definitions and categorizations, with overlapping symptoms, diagnostic criteria, and management strategies.2,3

Several personal and professional issues may predispose an individual to developing vicarious trauma. Factors that increase risk include a personal history of trauma, negative coping behaviors, a lack of social support, instability in non–work-related areas of one's life, and working with patient populations who disproportionately experience trauma.1 Issues in the professional environment can also increase vicarious trauma vulnerability, such as excessive workload, unclear scope of work, and dissonance between institutional public-facing commitments to vulnerable populations and internal policies and incentives.3

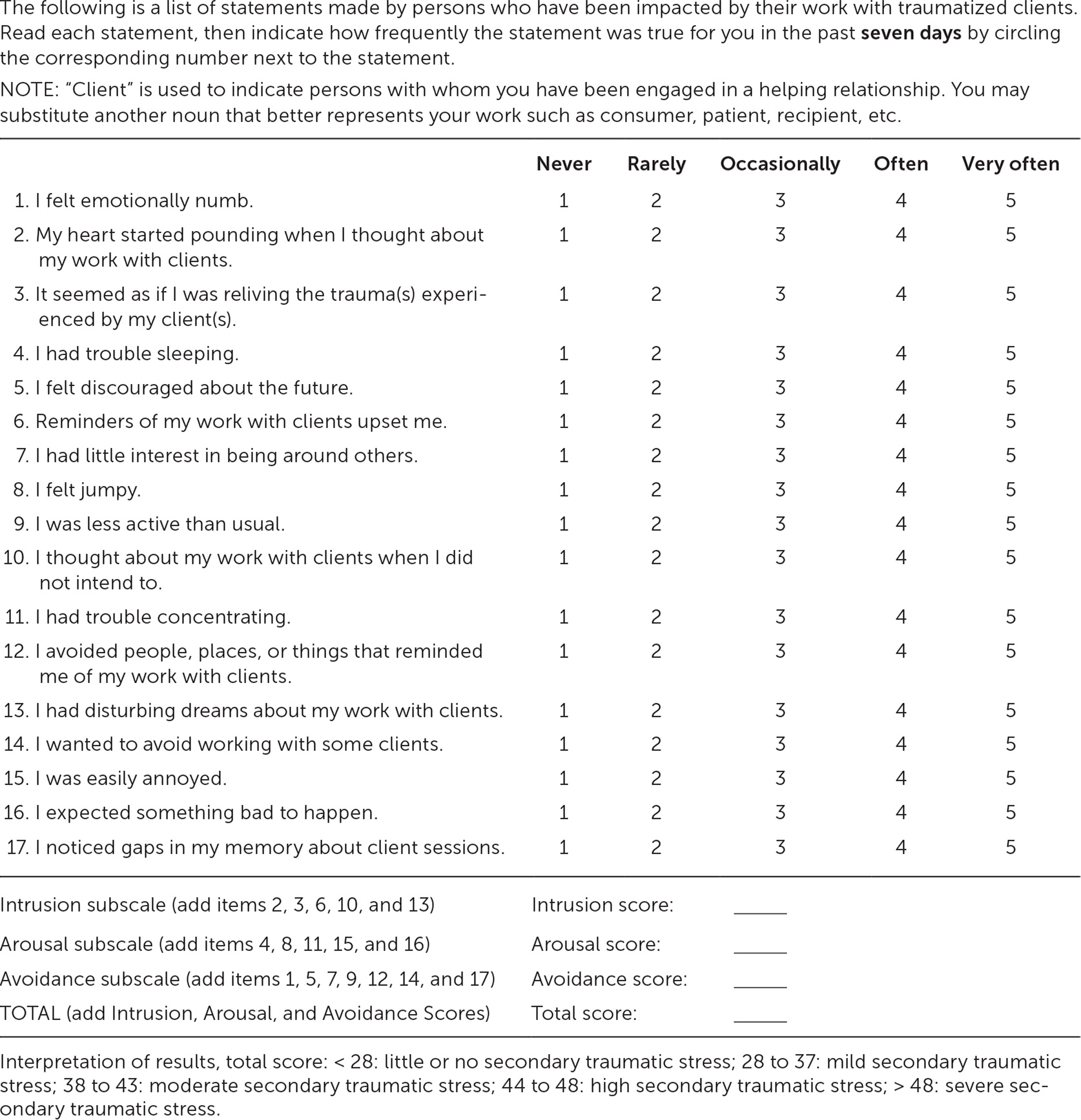

Vicarious trauma symptoms can manifest in one's professional and personal life. For example, a physician who is usually affable and empathetic may become increasingly irritable toward patients and colleagues, distant with family and friends, or overprotective in parenting. Health care–related manifestations can include excessive worrying (e.g., that a patient missed an appointment because they are hurt or have died), delays in completing the charts of patient encounters that involve upsetting stories, overreacting to unexpected environmental noises (e.g., overhead pages in the clinic, telephones ringing in examination rooms), experiencing visual images of examining an abuse-related injury in a setting outside of work, or finding it difficult to watch previously tolerable entertainment (e.g., shows or movies involving crime and violence). Symptoms of vicarious trauma are similar to those of posttraumatic stress disorder, with domains of intrusive thoughts, avoidant behaviors, and alterations in arousal.4 The Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale is a validated 17-item questionnaire that was developed to measure symptoms associated with the indirect exposure to traumatic events because of one's professional relationships with traumatized individuals (Figure 1).4 This scale can be used to evaluate vicarious trauma–related posttraumatic stress disorder.5

Management and Prevention

We discuss a variety of tools and techniques that are available for physicians and health care systems to address vicarious trauma with patients, colleagues, and staff.

CASE SCENARIO #1

When addressing vicarious trauma with patients, as in Case #1, it is helpful to obtain a more detailed history, including the duration and range of symptoms. Introducing the topic of vicarious trauma can facilitate patients' insight into factors driving symptoms and foster a path toward addressing underlying causes. The Secondary Traumatic Stress Scale can be used to elicit symptoms and as a tool to educate and facilitate discussion on vicarious trauma.4 Engaging in therapy is critical in managing vicarious trauma, particularly given the vast effect trauma symptoms can have on mental health. As patients initiate the sometimes protracted process of connecting with mental health services, routine primary care approaches can be used to manage acute, disruptive vicarious trauma symptoms, including coaching on sleep hygiene techniques for insomnia and reviewing strategies for alleviating anxiety. If indicated, physicians can also support their patients by facilitating workplace accommodations to decrease the exposure and/or impact of vicarious trauma or in securing medical leave.

CASE SCENARIO #2

Taking the initiative to address vicarious trauma with a colleague, as in Case #2, can be challenging. Because vicarious trauma can coexist with or exacerbate other conditions with similar workplace behavior manifestations, including depression and substance use disorder,6 its presence may be difficult to confirm. Approaching a colleague who you suspect is having vicarious trauma can include taking time to communicate and listen in a private setting and/or helping your colleague connect with Balint groups or similar regular gatherings where physicians can discuss complex issues that arise during clinical encounters.7 Individuals experiencing vicarious trauma may not recognize that their difficulties are related to their occupational trauma exposure, potentially leading to defensiveness or embarrassment, particularly when raised by a team member. In such cases, methods of support that directly address the colleague's daily workload may be helpful, such as encouraging strategic scheduling. This can involve anticipating and limiting the number of emotionally challenging cases during a clinic session and deliberately scheduling such visits at times when the physician feels the most equipped with emotional reserve and ability to focus, such as the first or last visit of a session. Trauma Stewardship: An Everyday Guide to Caring for Self While Caring for Others offers practical strategies for personal and professional approaches to manage vicarious trauma.2

System-level change is important in preventing and addressing vicarious trauma because all staff, including front-office employees, interpreters, and physicians, can be affected. Health care organizations should provide training to increase vicarious trauma awareness and inform employees of its various manifestations and specific strategies to prevent and combat it. Ensuring that all staff have adequate supervision and support is essential; organizational policies and procedures that ensure staff have well-balanced patient panels, paid time off, and access to mental health resources are also important.8 Toolkits and resources to promote organizational trauma responsiveness are available from the Office for Victims of Crime.1

Vicarious trauma is an occupational hazard for those in “helping professions,” including family physicians. Recognizing and addressing the signs and symptoms of vicarious trauma, while engaging in organizational efforts for its prevention and mitigation, will potentially promote the health of individuals and quality of patient care.