Am Fam Physician. 2021;103(10):597-604

Author disclosure: Dr. Hill does not have a formal relationship with any pharmaceutical company to disclose. A public database revealed a listing for Intrarosa, but this was not a direct payment or a violation of our conflict-of-interest policy. Dr. Taylor has no relevant financial affiliations to disclose.

Dyspareunia is recurrent or persistent pain with sexual intercourse that causes distress. It affects approximately 10% to 20% of U.S. women. Dyspareunia may be superficial, causing pain with attempted vaginal insertion, or deep. Women with sexual pain are at increased risk of sexual dysfunction, relationship distress, diminished quality of life, anxiety, and depression. Because discussing sexual issues may be uncomfortable, clinicians should create a safe and welcoming environment when taking a sexual history, where patients describe the characteristics of the pain (e.g., location, intensity, duration). Physical examination of the external genitalia includes visual inspection and sequential pressure with a cotton swab, assessing for focal erythema or pain. A single-digit vaginal examination may identify tender pelvic floor muscles, and a bimanual examination can assess for uterine retroversion and pelvic masses. Common diagnoses include vulvodynia, inadequate lubrication, vaginal atrophy, postpartum causes, pelvic floor dysfunction, endometriosis, and vaginismus. Treatment is focused on the cause and may include lubricants, pelvic floor physical therapy, topical analgesics, vaginal estrogen, cognitive behavior therapy, vaginal dilators, modified vestibulectomy, or onabotulinumtoxinA injections.

Dyspareunia, recurrent or persistent painful sexual intercourse, is common and can affect women's mental and physical health and relationships.1,2 The prevalence of dyspareunia in the United States is approximately 10% to 20% and varies by age and population.3 Women with sexual pain are at increased risk of sexual dysfunction, relationship distress, diminished quality of life, anxiety, and depression.2,4 Many women seeking medical care for sexual pain report believing that their concerns are invalidated and dismissed.5 Dyspareunia is a complex disorder often involving both psychosocial and physical conditions, requiring a detailed genitourinary examination and clinician knowledge of risk factors and the multifactorial nature of the disorder. Recommendations for treating dyspareunia are determined by the patient's current anatomy.

Risk Factors

Several risk factors should prompt clinicians to ask about painful sex.2,4,6,7 Demographic risk factors include younger age; White race; lower socioeconomic status; and being in the postpartum, perimenopausal, or postmenopausal period. Psychosocial risk factors include depression, anxiety, low sexual satisfaction, and a history of sexual abuse. Women who have had a vacuum-assisted or forceps vaginal delivery, are breastfeeding, or have had pelvic floor surgery are also at an increased risk. Sexual pain may occur with other conditions that cause pelvic pain, such as irritable bowel syndrome, musculoskeletal disorders, and fibromyalgia.1

History

Clinicians should create a safe and welcoming environment where patients feel comfortable discussing their sexuality. This includes avoiding moral or religious judgment, using neutral and inclusive terms that avoid assumptions about behavior or orientation, and recognizing that discussing sexual issues may be uncomfortable for the patient and clinician.8 A detailed history includes asking patients to describe the characteristics of the pain (e.g., location, intensity, duration); symptoms involving other organs, such as the bladder, bowel, or musculoskeletal system; sexual behaviors that cause pain; psychological history and symptoms; and current medical conditions. Additional history should include prior treatment for sexual dysfunction, whether the patient has recently given birth or is breastfeeding, and whether there is a history of intimate partner violence or sexual abuse.9

Determining which sexual activities are painful can suggest specific diagnoses. Patients who have pain with vaginal entry may have atrophy, inadequate lubrication, pelvic floor dysfunction, vaginitis, vulvodynia, or vaginismus, whereas patients who have deeper pain may have endometriosis or structural or anatomic abnormalities, such as uterine retroversion2,10 (Table 11,2,10–19).

| Diagnosis | Entry or deep | Historical clues | Examination findings | Additional testing | Treatment options |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vulva and vagina | |||||

| Dermatologic diseases (e.g., lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, contact dermatitis)11 | Entry | Burning, dryness, pruritus | Visible skin changes (dependent on condition) | Biopsy may be necessary to confirm diagnosis | Usually topical steroids; depends on diagnosis |

| Inadequate lubrication12–14 | Both | Dryness; history of diabetes mellitus; history of chemotherapy or use of progestogens, aromatase inhibitors, tamoxifen, or gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists | Vulva may be normal or appear dry | Usually unnecessary | Discontinuation of causative medication if possible; use of vaginal moisturizers or lubricants |

| Pelvic floor dysfunction2,15,16 | Both | Difficulty evacuating stool or emptying bladder; aching after intercourse; pain in lower back, thighs, or groin | Painful vaginal muscles just inside of the hymen during single-digit examination | Usually unnecessary | Pelvic floor physical therapy, gabapentin (Neurontin), trigger point injections with local anesthetics or onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox), neuromodulation |

| Vaginal atrophy12 | Both | Burning, dryness | Tissue may appear pale and dry (although may appear normal in early menopause) | Usually unnecessary | Vaginal moisturizers or lubricants, topical estrogen, ospemifene (Osphena), prasterone (Intrarosa) |

| Vaginismus17 | Entry | Difficulty achieving penetration; possible history of anxiety, sexual abuse or trauma, or other causes of painful penetration; sometimes no prior risk factors are present | Involuntary contraction of pelvic floor muscles with attempted insertion of finger or small speculum | Identify psychosocial factors, such as sexual abuse or anxiety | Multidisciplinary approach includes cognitive behavior therapy, psychotherapy, relationship and sexual counseling, lubricants, sequential vaginal dilators, and onabotulinumtoxinA injection |

| Vaginitis2 | Both | Discharge, burning, or odor | Vaginal discharge | pH testing, microscopy, polymerase chain reaction swab as indicated | Antibiotic or antifungal therapy according to diagnosis |

| Vulvodynia1,2,11,18 | Entry | Chronic burning, tearing, aching, or stabbing vulvar pain of at least three months' duration | Vulva may be visually normal or may have focal areas of erythema around the vestibule and hymen that are painful, as elicited by a cotton swab | Assess for comorbidities, such as depression, anxiety, a history of childhood sexual or physical abuse, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis, musculoskeletal disorders, or pelvic floor muscle dysfunction; as indicated, rule out other etiologies (e.g., testing for vaginitis) | Patient education about vulvar hygiene and using cotton underwear and pads, 2% lidocaine jelly or ointment applied by cotton ball placed on vulva at bedtime, amitriptyline, oral or compounded vaginal gabapentin, compounded vaginal muscle relaxants, estrogen, selective serotonin or norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, pelvic floor physical therapy, cognitive behavior therapy, amitriptyline, surgical excision |

| Bladder | |||||

| Interstitial cystitis19 | Deep | Urinary urgency, frequency, and nocturia | Pain with palpation of bladder base | Interstitial cystitis questionnaire; bladder instillation; cystoscopy | Dietary modification; antispasmodics; cimetidine (Tagamet); amitriptyline |

| Uterus and adnexa | |||||

| Ovarian masses2 | Deep | Lateralized pain with intercourse | Pain with adnexal palpation | Transvaginal ultrasonography | Observation or laparoscopy as indicated |

| Uterine retroversion10 | Deep | Pain may be related to sexual position; may be associated with endometriosis | Retroverted uterus, may be painful when moved cephalad | Usually unnecessary; transvaginal ultrasonography helpful to rule out myomas | Modify sexual positions; vaginal pessary; hysterectomy |

| Pelvis | |||||

| Adhesions or chronic pelvic inflammatory disease2 | Deep | May have lateralized, sharp pain; history of pelvic inflammatory disease or pelvic surgery | Possible fixation of pelvic organs on bimanual examination | Pelvic imaging to rule out other diagnoses | Nonopioid analgesics; laparoscopic adhesiolysis |

| Endometriosis2 | Deep | Family history; dysmenorrhea common | Generalized pelvic tenderness; nodularity may be noted in cul-de-sac during rectovaginal examination | Generally unnecessary; laparoscopy if diagnosis uncertain or patient desires | Nonopioid analgesics, combined oral contraceptives, progestogens, levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena), elagolix (Orilissa), laparoscopic excision |

Physical Examination

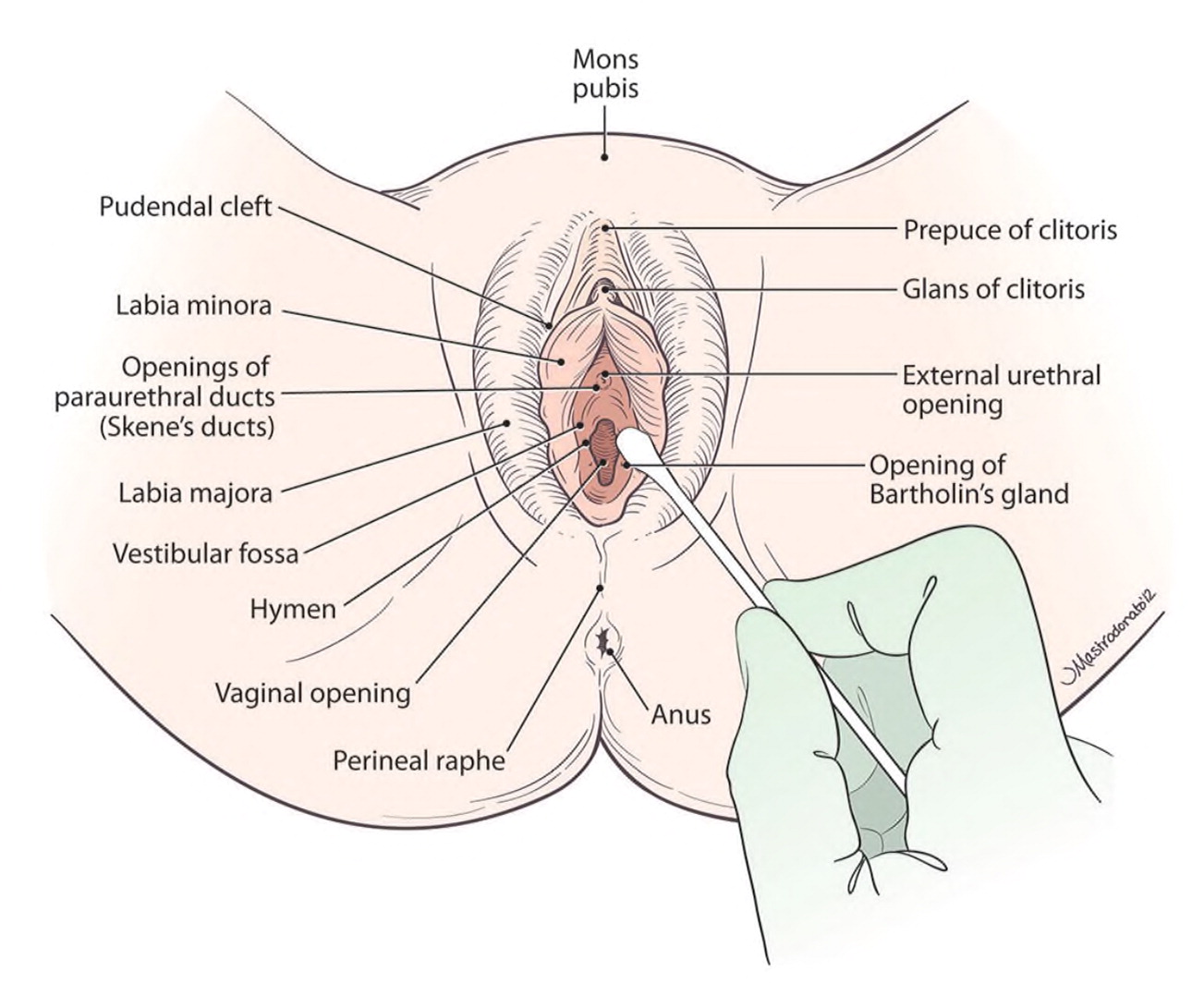

Patients with dyspareunia may have anxiety about genital examinations. It can be helpful to explain to the patient why the examination is necessary and how it may help with diagnosis and treatment.9 Offering the patient a mirror to follow along during the examination may help with patient education about normal anatomy and aid in pinpointing painful areas. Clinicians should visually inspect the external genitals, evaluating for atrophy, discoloration, erythema, lesions, or trauma (Figure 120). For patients reporting focal pain, clinicians should localize the pain by using a small cotton swab to systematically press on the external genital tissue, including the hymen.

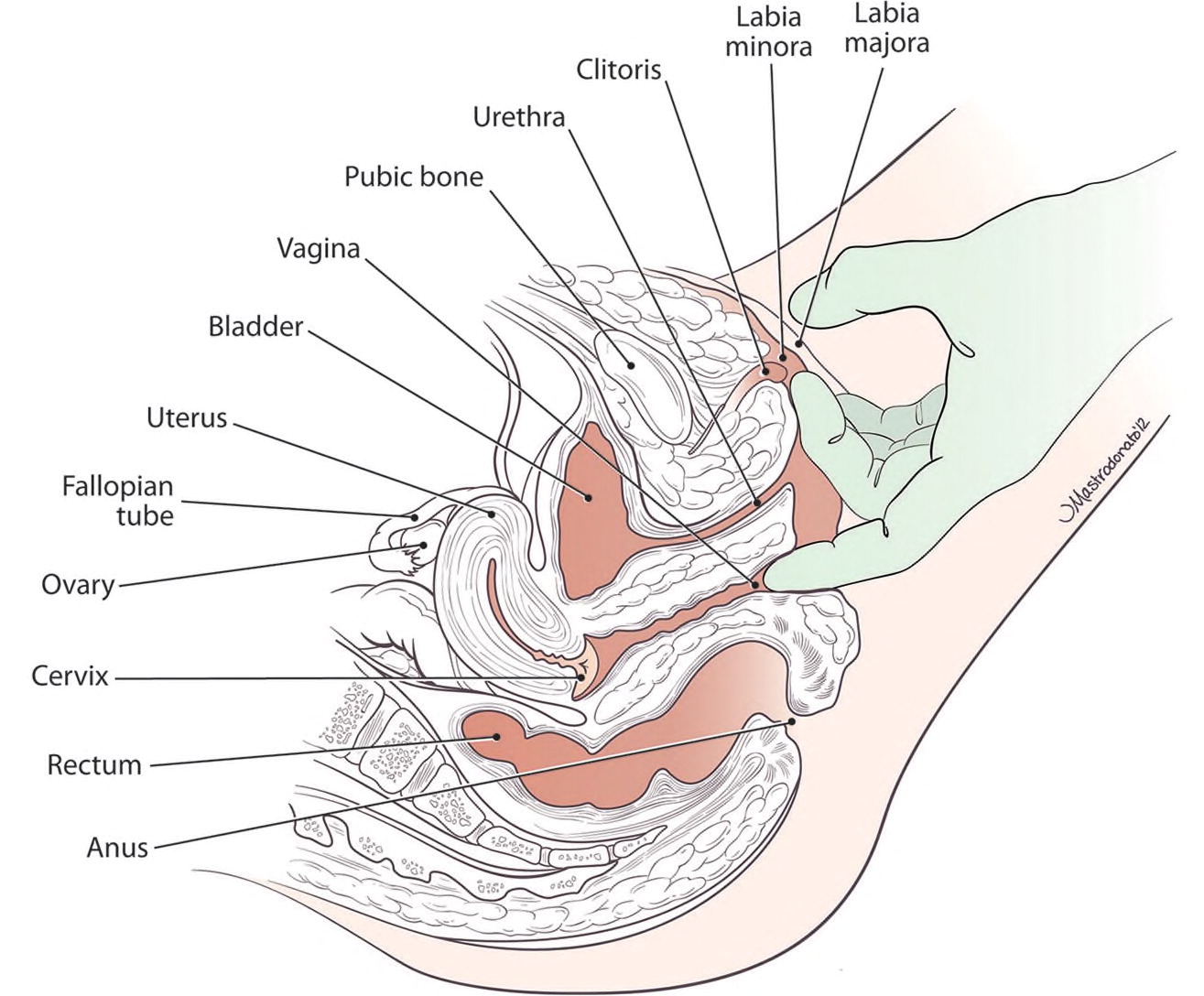

Next, the clinician should palpate the vagina beginning with a lubricated single digit, assessing for a narrow introitus or pain with palpation of the pelvic floor 16 (Figure 220). Palpating slowly through 360 degrees will allow the clinician to evaluate the pelvic floor muscles (levator ani, obturator internus, and piriformis) to determine whether tension or pain occurs (unilaterally or bilaterally) and to assess for pain from the urethra, bladder base, and cervix.2

If tolerated, some clinicians may find it easier to insert a second finger for the remainder of the examination. While the patient relaxes the abdominal muscles, the clinician gently elevates the cervix to palpate the uterus (if present) and each adnexa. Uterine prolapse or retroversion may cause pain when the uterus is gently moved cephalad. Women with deep dyspareunia, particularly those with rectal pain or dyschezia, may have rectovaginal or uterosacral nodularity that is palpable during rectovaginal examination. If indicated by history or examination findings, the clinician should perform a speculum examination to assess for vaginitis and order cervical cytology testing to screen for sexually transmitted infections.

Differential Diagnosis

INADEQUATE LUBRICATION AND VAGINAL ATROPHY

Friction occurring during penetrative sex can cause trauma to the vulvar and vaginal epithelium and subsequent pain. Several conditions can cause inadequate lubrication, including premature ovarian failure, bilateral oophorectomy, menopause, pituitary tumors, postpartum status (including breastfeeding), diabetes mellitus, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy.12,13 Medications associated with vaginal dryness include gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists, selective estrogen receptor modulators, tamoxifen, aromatase inhibitors, progestogens, and danazol.12

Treatment of inadequate lubrication includes the use of vaginal lubricants or moisturizers.14 Vaginal moisturizers are applied several times per week to hydrate the vaginal mucosa and compare favorably to vaginal estrogen for reducing dryness, whereas lubricants are used only during intercourse. Water- and silicone-based lubricants can be used with condoms. Some patients may prefer coconut, olive, or vegetable oils, but these cannot be used with condoms.14

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause, a recent term that encompasses vulvovaginal atrophy, dryness, and other effects of diminished estrogen, affects up to 50% of women during menopause and can cause dyspareunia.12 Although genitourinary syndrome of menopause is common, about 25% of patients with symptoms seek care, perhaps from embarrassment or because they believe such symptoms are a normal part of aging.21 Because vulvar tissue may appear normal in early menopause, treatment should be guided by symptoms.

Vaginal lubricants and moisturizers may provide temporary relief for patients with genitourinary syndrome of menopause. Vaginal estrogen is the most effective therapy for symptomatic women.12 Both systemic and vaginal estrogen are effective, but vaginal therapy has less systemic absorption and provides faster relief.12 A Cochrane review found that vaginal creams, rings, and tablets all have similar effectiveness for treating genitourinary syndrome of menopause.22

Women with a history of breast cancer or who prefer nonestrogen treatment options for moderate to severe dyspareunia due to genitourinary syndrome of menopause may benefit from ospemifene (Osphena) or prasterone (Intrarosa). Ospemifene is an oral selective estrogen receptor modulator effective for treating menopausal dyspareunia.23 Ospemifene is contraindicated in patients at risk of thromboembolism.12 Prasterone is a vaginal dehydroepiandrosterone formulation shown to increase epithelial thickness and to decrease pain with intercourse.24

According to Goodrx.com, Osphena costs $223, and Intrarosa costs $207 for a one-month supply; neither drug is available as a generic. A 30-day estradiol insert (Femring) costs $50 for generic and $600 for the brand. A 30-day supply of estradiol tablets (Vagifem) costs $50 for generic and $185 for the brand, and one tube of estradiol vaginal cream (Estrace) costs $50 for generic and $365 for the brand.25

Vaginal laser therapy to increase vaginal epithelial thickness and decrease dyspareunia is a newer therapy for genitourinary syndrome of menopause. A randomized prospective comparison of fractionated carbon-dioxide laser therapy and estrogen cream found nonstatistically significant improvements in genitourinary syndrome of menopause symptoms and sexual function at six months with both treatment options. About 70% to 80% of women reported that they were satisfied with either treatment.26 Although this study found that no serious adverse events occurred with laser therapy, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration issued a statement cautioning that it has not approved any energy-based devices for vaginal relaxation or the treatment of vulvovaginal atrophy and that such treatment may cause dyspareunia, scarring, and burns.27 Further, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists concludes that more data are needed to evaluate the safety, effectiveness, adverse events, and long-term outcomes of laser therapy for treating genitourinary syndrome of menopause.14

PELVIC FLOOR DYSFUNCTION

Pelvic floor muscle dysfunction may cause pain with vaginal insertion or during intercourse and may cause urinary dysfunction and defecatory and pelvic pain.15 To assess the pelvic floor anatomy and function, the clinician should first ask the patient to contract the pelvic floor muscles, which should lift the perineum.15 Muscle tenderness is assessed by inserting a lubricated finger into the introitus and pressing against the pelvic floor by rotating the finger 360 degrees16 (Figure 220). Pelvic floor physical therapy should be considered when appropriate, preferably with someone specialized in treating pelvic floor disorders.15 Other treatments that are used instead of, or in conjunction with, physical therapy include neuropathic pain modulators, such as gabapentin (Neurontin); trigger point injections with local anesthetics or onabotulinumtoxinA (Botox); and neuromodulation of the posterior tibial, pudendal, or sacral nerves using nerve stimulators.2,15,28

VULVODYNIA

Vulvodynia is defined as chronic genital pain of at least three months' duration that has no known etiology. The pain can be provoked (triggered by touch, such as inserting a tampon or attempted sexual intercourse), unprovoked (occurring without touch), or mixed.29 Vulvodynia is further categorized as generalized (pain affecting the entire vulva) or localized (pain specific to the vestibule and introitus, formerly known as vulvar vestibulitis).29,30 Vulvodynia is common, with a lifetime prevalence of 10% to 28% in reproductive-aged women.29

Women with vulvodynia may report burning, tearing, aching, or stabbing pain.11 Pruritis is uncommon with this condition and should suggest another diagnosis.11 Vulvodynia is associated with several comorbidities, such as fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis, and pelvic floor muscle dysfunction; psychosocial factors include depression, anxiety, and a history of childhood sexual or physical abuse.30 Clinicians should assess for and treat these comorbid conditions when managing patients with vulvodynia.1,2,11

Patients with provoked vulvodynia may have erythema and localized tenderness adjacent to the hymen, usually on the posterior vestibule, that are best identified with sequential pressure from a cotton swab. Documenting the location with reference to the “clock face” may assist with future examinations to determine whether therapy is successful. Cultures, biopsy, or microscopy can be performed as indicated to rule out other causes of vulvar pain (e.g., candidal or bacterial infections; dermatologic conditions, such as lichen sclerosus, lichen planus, or contact dermatitis).

Because vulvodynia is a multifactorial disorder, treatment will likely require a multidisciplinary team approach.2 Many treatment options have been reported, although often without significant supporting evidence.31 Patients may benefit from education about vulvar hygiene, such as avoidance of harsh detergents or perfumed vulvar products, washing with only soap and water, wearing 100% cotton underwear, and using cotton menstrual pads.18 Medical treatment options include topical agents, such as 2% lidocaine jelly or ointment applied by cotton ball at bedtime, estrogen, compounded gabapentin, and compounded vaginal muscle relaxants. Pelvic floor physical therapy; cognitive behavior therapy; onabotulinumtoxinA pelvic floor injections; and oral medications, including amitriptyline, gabapentin, or selective serotonin or norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, may also be helpful.1,2,11 If medical treatment is unsuccessful for patients with provoked vulvodynia, surgical excision (e.g., modified vestibulectomy) is an option.2

POSTPARTUM DYSPAREUNIA

Postpartum sexual dysfunction, including dyspareunia, is common. Among women who have had their first vaginal delivery, approximately 40% report painful sex three months postpartum and 20% at six months postpartum.32 Breastfeeding can cause vaginal dryness and pain with penetration because of diminished estrogen.14 Vacuum-assisted delivery, forceps delivery, and perineal lacerations are associated with prolonged dyspareunia, lasting at least six months after delivery.32 Few women discuss postpartum sexual dysfunction with their maternity care clinician. Clinicians should question all postpartum patients about sexual function. A validated screening questionnaire, such as the Female Sexual Function Index (https://www.fsfiquestionnaire.com), may be used.33

If the examination rules out painful perineal scarring, granulation tissue, pelvic floor muscle tenderness, laceration breakdown, or infection, use of lubricants during sexual activity may alleviate pain. Women with poorly healed lacerations and significant anatomic distortion may benefit more from surgical repair than pelvic floor physical therapy.34

VAGINISMUS

Vaginismus (involuntary contraction of the pelvic floor muscles with attempted vaginal penetration) is now combined with dyspareunia into the term genitopelvic pain/penetration disorder.35 Vaginismus leads to fear or anxiety about penetration, causing pelvic floor muscle constriction, which is distinct from causes of entry dyspareunia, such as infections, vulvodynia, or pelvic floor dysfunction.17 Primary vaginismus occurs in patients who have never had painless penetration, whereas secondary vaginismus occurs when the patient previously had painless penetration but now reports pain.36 Although vaginismus may be associated with anxiety, fear, traumatic sexual experiences, or medical conditions that cause painful penetration, some patients with vaginismus do not have any antecedent risk factors.17

Successful multidisciplinary treatment of vaginismus may include cognitive behavior therapy, psychotherapy, relationship and sexual counseling, vaginal lubricants, sequential vaginal dilators, and onabotulinumtoxinA injection.17

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Seehusen, et al.,20 and Heim.37

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms dyspareunia, vaginismus, vulvar vestibulitis, pelvic floor disorders, sexual pain, vulvodynia, and vestibulodynia. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, clinical trials, and reviews. Also searched were Ovid, Clinical Key, UpToDate, Cochrane Library, Web of Science, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality evidence reports, and Essential Evidence Plus. Search dates: February 1, 2020, and January 23, 2021.