Am Fam Physician. 2021;103(12):745-752

Published online: April 19, 2021.

†Deceased

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Obstetric lacerations are a common complication of vaginal delivery. Lacerations can lead to chronic pain and urinary and fecal incontinence. Perineal lacerations are defined by the depth of musculature involved, with fourth-degree lacerations disrupting the anal sphincter and the underlying rectal mucosa and first-degree lacerations having no perineal muscle involvement. Late third-trimester perineal massage can reduce lacerations in primiparous women; perineal support and massage and warm compresses during the second stage of labor can reduce anal sphincter injury. Conservative care of minor hemostatic first- and second-degree lacerations without anatomic distortion reduces pain, analgesia use, and dyspareunia. Minor hemostatic lesions with anatomic disruption can be repaired with surgical glue. Second-degree lacerations are best repaired with a single continuous suture. Lacerations involving the anal sphincter complex require additional expertise, exposure, and lighting; transfer to an operating room should be considered. Limited evidence suggests similar results from overlapping and end-to-end external sphincter repairs. Postdelivery care should focus on controlling pain, preventing constipation, and monitoring for urinary retention. Acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be administered as needed. Opiates should be avoided to decrease risk of constipation; need for opiates suggests infection or problem with the repair. Osmotic laxative use leads to earlier bowel movements and less pain during the first bowel movement. Simulation models are recommended for surgical technique instruction and maintenance, especially for third- and fourth-degree repairs.

Grading of Lacerations

FIRST- AND SECOND-DEGREE LACERATIONS

First-degree lacerations involve only the perineal skin without extending into the musculature.1 Second-degree lacerations involve the perineal muscles without affecting the anal sphincter complex.

THIRD-DEGREE LACERATIONS

| Degree | Description |

|---|---|

| First | Laceration of perineal skin only |

| Second | Laceration involving the perineal muscles but not involving the anal sphincter |

| Third | Laceration involving the anal sphincter muscles

|

| Fourth | Laceration involving the anal sphincter complex and rectal epithelium |

The majority of obstetric anal sphincter injuries are third-degree lacerations that involve the anal sphincter complex without disrupting the rectal mucosa.1 The anal sphincter complex comprises the larger external anal sphincter containing striated muscle and a distinct capsule plus the small internal anal sphincter of involuntary smooth muscle that often cannot be identified.

FOURTH-DEGREE LACERATIONS

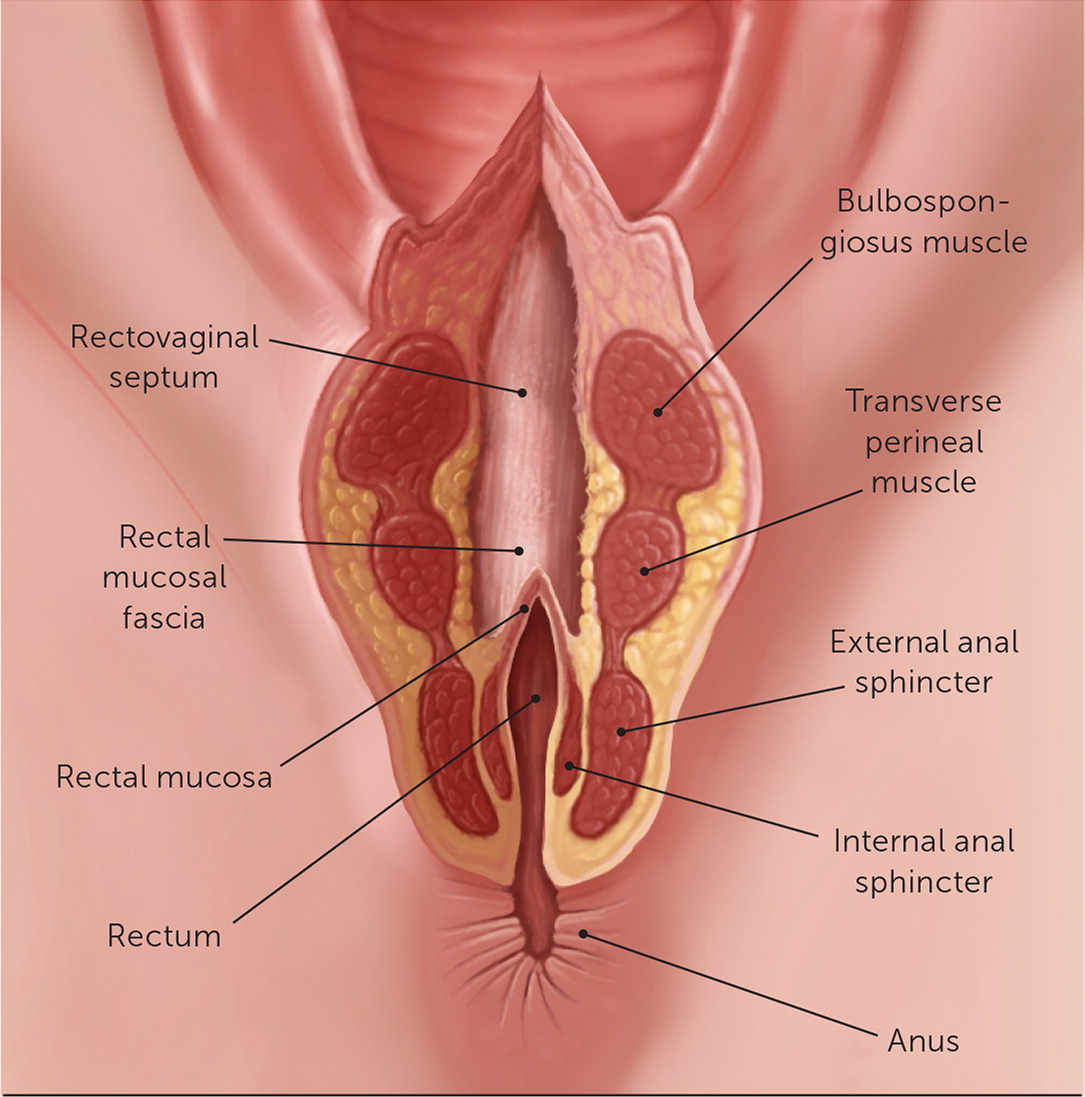

Fourth-degree lacerations are the most severe, involving the rectal mucosa and the anal sphincter complex.1 Disruption of the fragile internal anal sphincter routinely leads to epithelial injury. Fourth-degree lacerations occur in less than 0.5% of patients.1 Figure 2 shows a fourth-degree perineal laceration.

Prevention of Obstetric Lacerations

BEFORE DELIVERY

A Cochrane review demonstrated that digital perineal self-massage starting at 35 weeks' gestation reduces the rate of perineal lacerations in primiparous women with a number needed to treat of 15 to prevent one laceration.5 Because the review included fewer than 2,500 patients, reductions could not be demonstrated for specific laceration grades. Women reported that self-massage was initially uncomfortable, unpleasant, and even painful, but nearly 90% would recommend the technique to others.6

DURING DELIVERY

Studies of prevention during delivery have focused on prevention of obstetric anal sphincter injuries. Most risk factors involve labor management, including labor induction, labor augmentation, use of epidural anesthesia, delivery with persistent occipitoposterior positioning, and operative vaginal deliveries7 (Table 21,8,9). Although epidural anesthesia increases risk of obstetric anal sphincter injuries through increased operative vaginal delivery, epidural use reduces lacerations overall.10

| Fetal risk factors |

| Large fetal weight (> 4,000 g [8 lb, 13.1 oz]) |

| Occipitotransverse or occipitoposterior position at delivery |

| Intrapartum risk factors |

| Delivery in lithotomy position |

| Epidural anesthesia (increases risk of severe lacerations, decreases overall lacerations) |

| Midline episiotomy |

| Operative vaginal delivery (i.e., forceps, vacuum) |

| Oxytocin use |

| Prolonged second stage of labor (> 60 minutes) |

| Maternal risk factors |

| 20 years or younger |

| Asian ethnicity9 |

| Nulliparity |

| Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery |

Several labor techniques can reduce anal sphincter injuries. During the second stage of labor, perineal massage and application of a warm compress to the perineum are beneficial.11 Perineal support during delivery, variably described as squeezing the lateral perineal tissue with the first and second fingers of one hand to lower pressure in the middle posterior perineum while the other hand slows the delivery of the fetal head, reduces obstetric anal sphincter injuries, with a number needed to treat of 37 in a systematic review.12,13

Routine episiotomy does not reduce anal sphincter lacerations and is not recommended.14 Mediolateral episiotomy is not protective for obstetric anal sphincter injuries, and midline episiotomy increases the risk.9 Neither delaying maternal pushing following full cervical dilation nor altering birthing position reduces obstetric anal sphincter injuries.15,16

Evaluation for Repair

INSPECTION AFTER DELIVERY

Lacerations following vaginal delivery most commonly occur in the perineal body. Thorough perineal inspection, including a digital rectal examination, is recommended following any vaginal delivery.8 Proper lighting and good visualization aid evaluation focused on hemostasis, anatomic distortion, and anal sphincter integrity.2

MANAGING MINOR LACERATIONS

First- and second-degree perineal lacerations occur in approximately 50% of women, and most do not result in adverse functional outcomes.1,2 A Cochrane review demonstrated identical clinical outcomes at eight weeks with first- and second-degree lacerations with and without surgical repair.2 Leaving hemostatic, anatomically approximated first- and second-degree perineal lacerations without repair reduces pain, analgesia use, and dyspareunia at three months postpartum.2 Conservative care is also associated with higher breastfeeding rates.17 Without long-term comparison of surgical and conservative care, ACOG leaves decisions to the physician's clinical judgment.1

VAGINAL AND VULVAR LACERATIONS

Vaginal and vulvar tearing most often occurs on the vaginal wall, introitus (i.e., periclitoral, periurethral), or labia. Typically, these lacerations are superficial and require repair only for persistent bleeding or anatomic distortion such as a labial avulsion, where removed tissue disrupts skin integrity.1

Laceration Repair Technique

ANALGESIA AND EXPOSURE

Before starting an obstetric repair, patient comfort should be verified; local anesthetic should be used if needed. Appropriate instruments and materials should be assembled (Table 38,18), and the perineum should be positioned at a comfortable height for the physician. Visualization and adequate lighting are essential. Transfer to an operating room should be considered to ensure optimal exposure and lighting when a third- or fourth-degree laceration is recognized.18 A knowledgeable repair team is also recommended, with expert consultation considered if a physician with experience in anal sphincter repair is not present.18

| Environment |

| Adequate anesthesia |

| Good lighting (consider operating room) |

| Instruments |

| Allis clamps |

| Forceps with teeth |

| Gelpi or Deaver retractor (for use in visualizing third- or fourth-degree perineal lacerations, deep vaginal lacerations) |

| Hemostats |

| Metzenbaum scissors |

| Needle driver |

| Suture scissors |

| Materials |

| 10-mL syringe with 22-gauge needle |

| Irrigation solution |

| Local anesthetic |

| Sponges |

| Sterile gloves |

| Surgical glue (possibly) |

| Sutures (Table 4) |

Several types of absorbable sutures have been demonstrated to be equivalent for perineal laceration repair.19 Absorbable synthetic sutures cause less short-term pain and pain medication use than catgut suture.20 Multifilament and monofilament absorbable sutures result in similar outcomes at six weeks postpartum.21

VAGINAL AND VULVAR LACERATIONS

Vaginal lacerations include disruption of the vaginal floor and side walls, and vulvar lacerations include periurethral, periclitoral, or labial tears within the introitus. Small tears of these structures are often superficial and hemostatic and can be left unrepaired.1,17 Closure methods have not been compared; interrupted or running sutures can be employed.

FIRST-DEGREE LACERATIONS: REPAIR OPTIONS

If first-degree lacerations require repair, consider use of surgical glue for hemostatic lesions. Surgical glue repairs are faster, require less local anesthetic, and cause less pain with similar functional and cosmetic results at six weeks post-partum.22 Sutures can be helpful to stop bleeding.

SECOND-DEGREE LACERATIONS: PERINEAL REPAIR

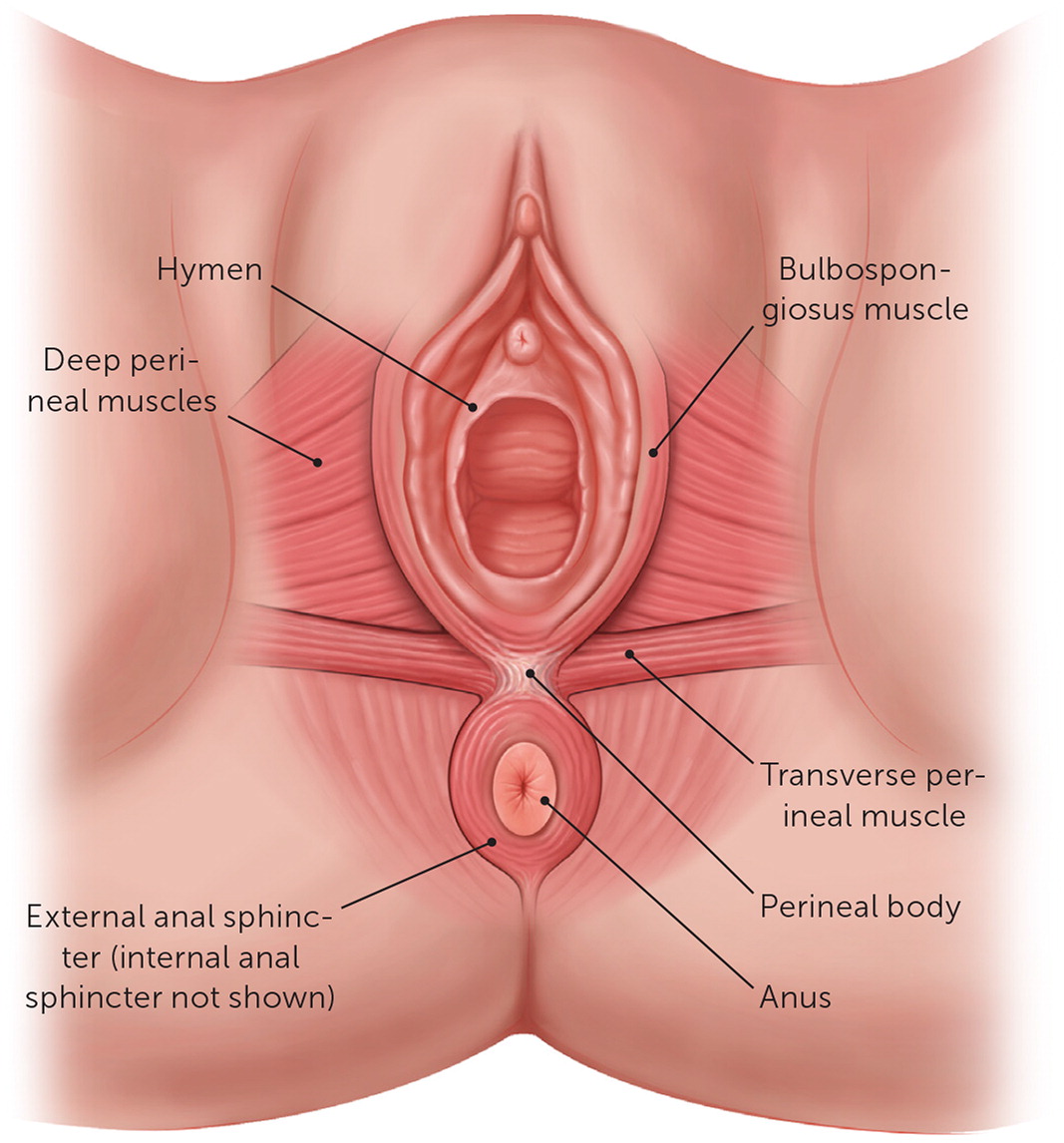

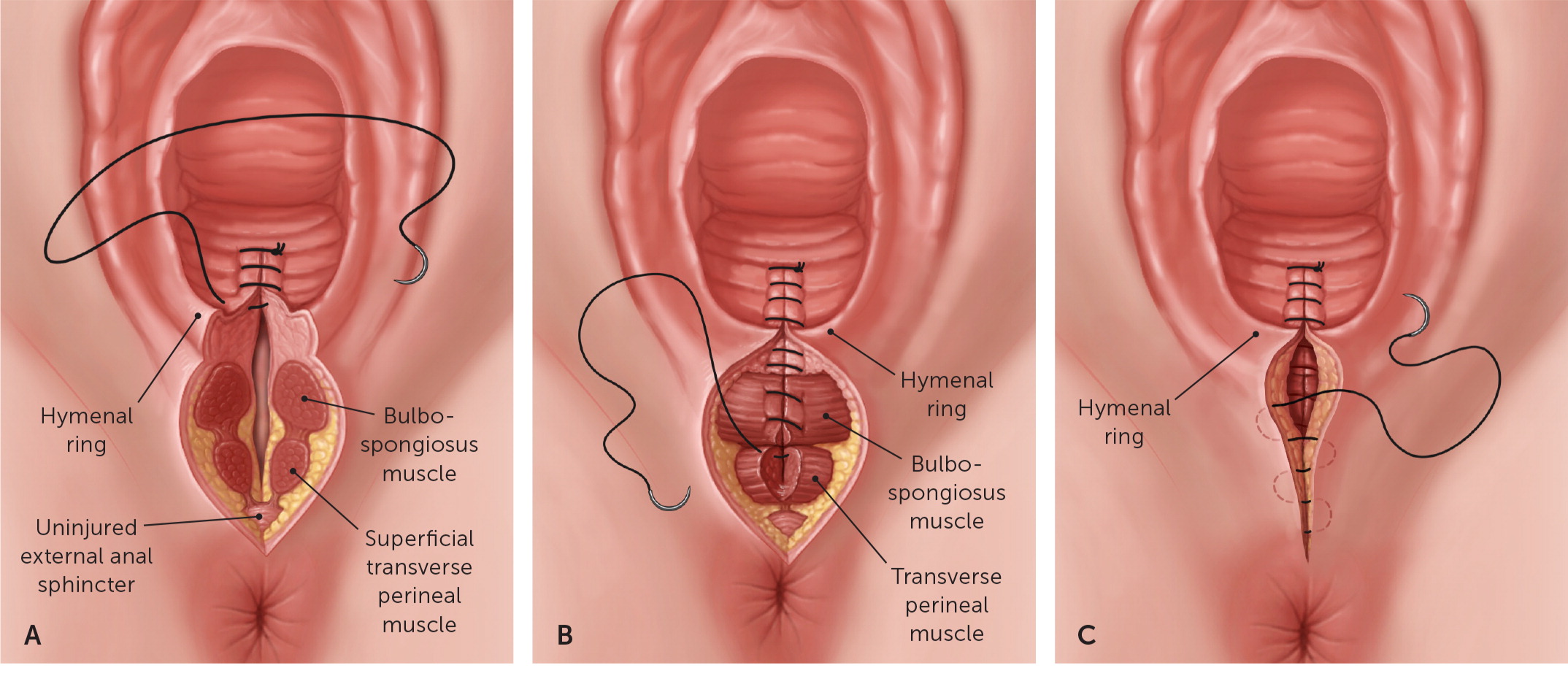

Repair of a second-degree laceration occurs in three stages: the rectovaginal fascia (also called the rectovaginal septum), the perineal body musculature, and the vaginal mucosa. Continuous suturing causes less short-term pain and pain medication use than interrupted suturing.23 The repair should be performed in a deep to superficial manner.8 In addition to verifying the integrity of the anal sphincter complex, before repairing the apex of the vaginal laceration, the bulbospongiosus and transverse perineal muscles of the perineal body should be identified (Figure 1 and Figure 3). A retractor can be employed if necessary to visualize the laceration apex within the vagina.

Vaginal Repair. After placing an anchoring suture 1 cm above the vaginal laceration apex, a running stitch is used to close vaginal mucosa and underlying fascia (Figure 3A). Locking sutures can be used if needed for hemostasis. After the running sutures are brought to the hymenal ring, proceed to the perineal muscle repair.

Perineal Muscle Repair. The ends of the bulbospongiosus muscle are reapproximated with one or two running sutures without locking, using an Allis clamp or needle to extend retracted muscle ends if necessary. The transverse perineal muscle ends are then similarly approximated (Figure 3B).

Rectovaginal Fascia Repair. The repair is finished by a running suture in the subcutaneous fascia ending at the hymenal ring (Figure 3C). The knot should be directed into the vagina behind the hymen. The skin does not require closure because a skin suture layer increases perineal pain at three months postpartum.24

THIRD-DEGREE LACERATIONS: ANAL SPHINCTER COMPLEX REPAIR

The anal sphincter complex is important to future continence and, therefore, quality of life. At five years after delivery, 17% of women with obstetric anal sphincter injuries report some liquid stool incontinence compared with 8% of women who experienced a vaginal delivery without obstetric anal sphincter injuries.3

There are two techniques for external sphincter repair when the sphincter is completely separated: end-to-end repair of the muscle or overlapping repair. Two small trials suggested that fecal incontinence rates are similar after either repair.25,26 If an external sphincter laceration is partial, the end-to-end repair is recommended for the lacerated portion vs. dividing the sphincter for an overlapping repair.1

In the overlapping technique, the free muscle ends are overlapped and joined by mattress sutures.27 This technique often requires dissection of the ends of the sphincter to allow overlap.28 For the end-to-end repair, the capsule is included to connect the most posterior part of the defect, followed by the superior and inferior elements of both ends, and ending with the anterior elements. Plain or figure-of-eight interrupted sutures can be used.28 Similar to any muscle repair, the connective tissue is the essential element to anchor the repair. Use of a 2-0 absorbable suture is recommended for the anal sphincter (Table 41,18,28). Despite limited evidence of ischemia or repair success with figure-of-eight sutures, British guidelines recommend against their use.20 Following sphincter repair, the remaining second-degree laceration is repaired, as discussed previously.

| Degree | Repair | Suture |

|---|---|---|

| Fourth | Anal mucosa | 4-0 braided polyglactin 910 (Vicryl), SH needle or 4-0 monofilament polydioxanone (PDS), SH needle |

| Perianal fascia and internal anal sphincter | 3-0 braided polyglactin 910 (Vicryl), SH needle or 3-0 monofilament polydioxanone, SH needle | |

| Third | External anal sphincter | 2-0 braided polyglactin 910 (Vicryl), CT-1 needle or 2-0 monofilament polydioxanone, CT-1 needle |

| Second | All: vaginal mucosa with perivaginal fascia, perineal body, and perineal fascia | 3-0 braided polyglactin 910 (Vicryl), CT-1 needle or 3-0 monofilament polydioxanone, CT-1 needle |

| First or vaginal | Any necessary due to bleeding or anatomic disruption | Consider surgical glue if hemostatic or 3-0 braided polyglactin 910 (Vicryl), CT-1 needle or 3-0 monofilament polydioxanone, CT-1 needle |

FOURTH-DEGREE LACERATIONS: RECTAL MUCOSA REPAIR

Because of the risk and infrequency of severe lacerations, these repairs should be completed by the most experienced physicians providing obstetric care.20 The rectal mucosa is repaired using an absorbable suture with a noncutting needle. A 4-0 absorbable suture is recommended (Table 41,18,28). After placing an anchor stitch with the knot within the rectum above the apex of the lesion, running sutures are placed within 0.5 cm to the anal verge.1 A second layer of sutures is recommended to reform the internal sphincter capsule and to protect the mucosal suture layer.1 The internal anal sphincter is small and difficult to identify; therefore, stabilization with an Allis clamp is often required.29 A 3-0 suture on a tapered needle is recommended for this layer17 (Table 41,18,28). A separate repair of the internal anal sphincter is sometimes recommended because of high fecal incontinence risk from postpartum internal anal sphincter defects.20,30 Following this repair, the external anal sphincter is repaired, as discussed previously.

After Delivery

After laceration repair, care should focus on controlling pain, preventing constipation, and monitoring for urinary retention. The patient can keep the area clean and dry by blotting after toileting.8

PREVENTING CONSTIPATION

PAIN CONTROL

During the first two days after delivery, local cooling applied to the perineum appears to reduce pain.33 Acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be sufficient for pain control.34 The use of opiates should be avoided to decrease risk of constipation; a need for opiates suggests infection or a problem with the repair.8 Topical anesthetics are not effective, and rectal suppositories are minimally effective and increase the risk of disruption of an anal sphincter repair.35,36

ACTIVITY

Recent ACOG recommendations view postpartum care as an ongoing, individualized process with women receiving care from the delivering physician within three weeks of delivery and continued care as needed to monitor for side effects.37 To prevent urinary incontinence, pelvic floor exercises are recommended beginning two to three days after delivery, with formal pelvic floor rehabilitation with biofeedback physiotherapy an option for patients with obstetric anal sphincter injuries.1,8

Physician Training in Perineal Repair

Physician training for obstetric laceration repairs can be challenging. Recognizing the importance of simulation for resident training, a detailed beef tongue simulation model has been recommended, with added anal canal and external anal sphincter to simulate a perineal tear.38 A video from the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons demonstrates a fourth-degree repair using this model (https://www.mdedge.com/obgyn/article/189883/surgery/instructional-video-fourth-degree-obstetric-laceration-repair-using). The Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics course offered by the American Academy of Family Physicians includes instruction on obstetric laceration repair.39

This article updates a previous article by Leeman, et al.29

Data Sources: PubMed searches were completed using the key terms obstetric laceration, perineal laceration, and obstetric anal sphincter injury. The searches included systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, review articles, and practice guidelines. References from these sources were monitored. We also searched the Cochrane database, Essential Evidence Plus, and Clinical Evidence. References in these resources were also searched. Search dates: March, April, May, and August 2020, and February 2021.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of the Air Force, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

Editor's Note: Dr. Arnold is contributing editor for AFP.

Additional Information: Dr. Leli passed away while deployed to the Middle East with the U.S. Air Force after completion of this article. An outstanding young physician, teacher, and role model, her legacy lives on in the students, residents, and colleagues whose lives she touched.