Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(4):395-402

Patient information: See related handout on osteomyelitis, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Osteomyelitis is an inflammatory condition of bone secondary to an infectious process. Osteomyelitis is usually clinically diagnosed with support from imaging and laboratory findings. Bone biopsy and microbial cultures offer definitive diagnosis. Plain film radiography should be performed as initial imaging, but sensitivity is low in the early stages of disease. Magnetic resonance imaging with and without contrast media has a higher sensitivity for identifying areas of bone necrosis in later stages. Staging based on major and minor risk factors can help stratify patients for surgical treatment. Antibiotics are the primary treatment option and should be tailored based on culture results and individual patient factors. Surgical bony debridement is often needed, and further surgical intervention may be warranted in high-risk patients or those with extensive disease. Diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease increase the overall risk of acute and chronic osteomyelitis.

Osteomyelitis is an inflammatory condition of bone secondary to infection; it may be acute or chronic. Symptoms of acute osteomyelitis include pain, fever, and edema of the affected site, and patients typically present without bone necrosis in days to weeks following initial infection. Chronic osteomyelitis develops after months to years of persistent infection and may be characterized by the presence of necrotic bone and fistulous tracts from skin to bone.1,2 Osteomyelitis is further classified by mechanism of infection as hematogenous or nonhematogenous. With hematogenous osteomyelitis, bacteria are seeded into bone secondary to a bloodstream infection and the condition is most common in children, older adults, and immunocompromised populations.1–3 Nonhematogenous osteomyelitis occurs from direct inoculation in the setting of surgery or trauma or with spread from contiguous soft tissue and joint infections.1,2

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| The preferred diagnostic criterion for osteomyelitis is a positive bacterial culture from bone biopsy, but clinical, laboratory, and radiographic findings can also inform a clinical diagnosis.9,12 | C | Consensus guideline and clinical review |

| Magnetic resonance imaging is the imaging modality of choice for suspected osteomyelitis, although plain film radiography is often done initially.13 | C | Consensus guideline |

| In adult patients hospitalized with chronic osteomyelitis, parenteral followed by oral antibiotic therapy appears to be as effective as long-term parenteral therapy.37,38 | B | Systematic review of eight small trials and a randomized controlled trial |

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not routinely use magnetic resonance imaging to diagnose bone infection (osteomyelitis) in the foot. | American Podiatric Medical Association |

Etiology

Methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus is the most frequently identified pathogen across all types of osteomyelitis, followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa and methicillin-resistant S. aureus. Hematogenous osteomyelitis is often monomicrobial and can occur from aerobic gram-negative rods or from P. aeruginosa or Serratia marcescens in injection drug users.4 Vertebral osteomyelitis is the most common type of hematogenous osteomyelitis and is polymicrobial in 5% to 10% of cases.1 Blood cultures may be negative if osteomyelitis develops following bacterial clearance from the bloodstream. Nonhematogenous osteomyelitis can be polymicrobial; S. aureus is the most common pathogen in addition to coagulase-negative staphylococci and gram-negative aerobes and anaerobes. Polymicrobial diabetic foot infections and decubitus ulcers may include Streptococcus species and Enterococcus species.1 Less common pathogens can be associated with certain clinical conditions, including immunocompromise (Aspergillus species, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Candida species), sickle cell disease (Salmonella species), HIV infection (Bartonella henselae), and tuberculosis (M. tuberculosis).1,5,6

Clinical Features

The clinical presentation of nonhematogenous osteomyelitis varies and symptoms are often non-specific. Signs and symptoms common to all sub-types may include pain, edema, and erythema. Acute osteomyelitis may present with a more rapid onset of symptoms (development over days) and is more likely to be associated with fever. Systemic symptoms are not common in chronic osteomyelitis, and the presence of fistulous tracts from skin to bone is diagnostic. Long-standing, nonhealing ulcers and nonhealing fractures may also be associated with chronic osteomyelitis.

Patients with diabetic neuropathy are at higher risk of developing osteomyelitis secondary to local spread from diabetic foot infections and unrecognized wounds.2 Smoking increases the risk of osteomyelitis from diabetic foot infections and healing fractures.7 Peripheral vascular disease and poorly healing wounds (e.g., decubitus ulcers) are more likely to lead to bone inflammation. Osteomyelitis secondary to diabetic foot ulcers can be difficult to diagnose given chronic changes from vascular insufficiency and ischemia.8

Hematogenous osteomyelitis often presents similarly to nonhematogenous disease. The most common form of hematogenous osteomyelitis is vertebral; patients often have back or neck pain and muscle tenderness, sometimes followed by fever. Hematogenous osteomyelitis may also occur in the sternoclavicular, pelvic, and long bones.9 When hematogenous osteomyelitis affects prepubertal children, it typically occurs in the metaphysis of long bones adjacent to growth plates, with a predilection for the tibia and femur.1

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of osteomyelitis should be considered in any patient with acute onset or progressive worsening of musculoskeletal pain accompanied by constitutional symptoms such as fever, malaise, lethargy, and irritability. Constitutional symptoms do not always occur in adults, especially in the setting of immunocompromise. The index of suspicion for osteomyelitis should be higher in patients with underlying conditions, including poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, neuropathy, peripheral vascular disease, chronic or ulcerated wounds, history of recent trauma, sickle cell disease, history of implanted orthopedic hardware, or a history or suspicion of intravenous drug use. A dedicated physical examination can increase the likelihood of diagnosing osteomyelitis if findings include erythema, soft tissue infection, bony tenderness, joint effusion, decreased range of motion, or exposed bone. The probe-to-bone test may be useful to rule out diabetic foot osteomyelitis in low-risk patients.10,11

The differential diagnosis of osteomyelitis includes soft tissue infection, gout, Charcot arthropathy, fracture, malignancy, bursitis, osteonecrosis, sickle cell vasoocclusive pain crisis, and SAPHO syndrome (synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, and osteitis). Uncertain clinical diagnosis should prompt further workup that includes laboratory evaluation and imaging (Table 12,9,12,13). Definitive diagnosis is made with a positive culture from biopsy of the affected bony structure. Polymerase chain reaction testing may help in the rapid diagnosis of organisms or for cultures taken after antibiotic therapy.12,14 Bone biopsy remains the diagnostic standard but is not always feasible. Some evidence suggests that biopsy should be reserved only for select cases because the results may not lead to treatment alterations.15

| Imaging studies (e.g., plain film radiography, magnetic resonance imaging, bone scintigraphy) demonstrating contiguous soft tissue infection or bony destruction |

| Clinical signs Chronic wound overlying surgical hardware Chronic wound overlying traumatic injury or fracture Exposed bone Persistent sinus tract Tissue necrosis overlying bone |

| Laboratory evaluation Elevated C-reactive protein level Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate Leukocytosis Positive blood cultures Thrombocytosis |

LABORATORY EVALUATION

Initial laboratory evaluation should include a complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, and blood cultures. Leukocytosis may be present in acute osteomyelitis, but it can be absent in chronic osteomyelitis.16,17 There is some evidence that thrombocytosis may positively predict osteomyelitis in patients with chronic leg ulcers.18 If inflammatory markers are elevated, they can be trended for clinical correlation.19,20 Positive blood cultures in association with radiographic evidence of osteomyelitis may prevent the need for a more invasive bone biopsy.21

IMAGING

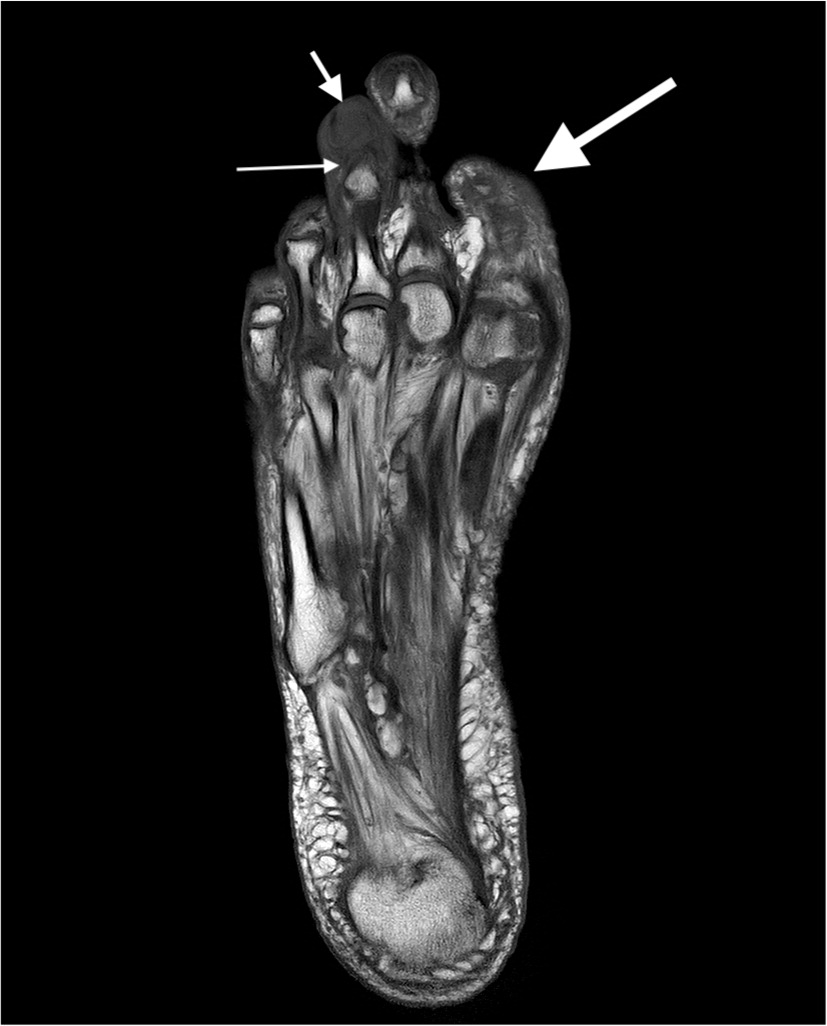

Plain film radiography is the first-line evaluation of suspected osteomyelitis. Advanced imaging is often needed for diagnosis following plain film radiography, because 50% to 75% of the bone matrix must be destroyed before lytic changes are evident on plain radiographs.22 Findings can include soft tissue swelling, osteopenia, cortical loss, bony destruction, and periosteal reaction12,23,24 (Figure 12). Advanced imaging can be guided by onset of symptoms and patient variables (Table 22,9,13,24–30). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has a high sensitivity and negative predictive value. Plain radiography and MRI are often both indicated and complementary13 (Figure 2, Figure 3, and Figure 4). Although contrast media is not required for diagnosis, it may be helpful to distinguish between abscess and phlegmon, especially in patients with chronic osteomyelitis.25–27

| Imaging modality | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plain film radiography (anteroposterior, lateral, and oblique views) | 14 to 54 | 68 to 70 | Preferred initial imaging modality; useful to rule out other bony pathology |

| MRI | 78 to 90 | 60 to 90 | Intravenous contrast media preferred; useful to distinguish between soft tissue and bone infection, and to determine extent of infection; less useful in areas with surgical hardware because of image distortion |

| Computed tomography | 67 | 50 | Contrast media preferred to help with soft tissue evaluation; may be used if MRI is contraindicated |

| Ultrasonography | NA | NA | Cannot be used to evaluate bone, but may be useful for identifying surrounding soft tissue changes or guiding needle aspiration; use for evaluation of suspected foreign body with negative results on radiography; may be used if MRI is contraindicated |

| Technetium-99 bone scintigraphy | 82 | 25 | Low specificity, especially if patient has had recent trauma or surgery; useful to differentiate osteomyelitis from cellulitis; SPECT improves sensitivity; may be used if MRI is contraindicated |

| Leukocyte scintigraphy | 61 to 84 | 60 to 68 | Combining with technetium-99 bone scintigraphy can increase specificity; may be used if MRI is contraindicated |

| Positron emission tomography | 96 | 91 | Expensive; limited availability; may be used if MRI is contraindicated |

MRI is more readily available and avoids radiation exposure, but positron emission tomography (PET) and single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) can also reliably diagnose osteomyelitis.25 In patients in whom MRI is contraindicated, a tagged leukocyte scan, computed tomography (CT), PET/CT, or sulfur colloid marrow scan can be appropriate; however, diagnosis may be impeded because of false-positive results from recent surgery or trauma, healed osteomyelitis, arthritis, bony tumors, Paget disease of bone, or reduced uptake secondary to necrosis and poor blood flow.13,29,30 Ultrasonography plays a complementary role to other modalities and may demonstrate inflammatory changes in the periosteum, particularly in children. Ultrasonography can be useful for identification of soft tissue abscess and helpful for abscess aspiration.13

Treatment

Osteomyelitis treatment requires a multifaceted approach that may include antibiotics, surgical intervention, and other modalities depending on multiple clinical factors, including clinical stage. Clinical staging guides decision-making when choosing specific surgical treatments and limits the need for amputation.31 The 2015 modification of the Cierny-Mader staging system (developed in 1985) is commonly used and classifies osteomyelitis based on the anatomic location and the physiologic condition of the patient.31,32 Anatomic types include medullary (stage 1), superficial (stage 2), localized (stage 3), and diffuse (stage 4), with higher stages requiring more complex surgical intervention.32 The physiologic condition of the patient (host) can be classified as type A (normal immune response and healthy vascular system), type B (local immunocompromise), or type C (noncandidate for surgery). In those classified as type C, treatment is expected to cause more harm than the disease process itself, so the focus of care shifts from cure to palliation.

ANTIBIOTICS

The choice of antibiotic therapy is specific to the culture results listed in Table 3.2,33–37 It should be tailored to the individual patient based on susceptibility. Specific antibiotic coverage is usually indicated. In hospitalized patients at risk of methicillin-resistant S. aureus, empiric antibiotic coverage is recommended. Delaying antibiotic therapy until cultures are available is recommended except in patients in whom urgent intervention is necessary, such as those with severe sepsis, epidural extension, or neurologic involvement. The addition of rifampin to other antibiotics may also improve cure rates, especially when prosthetic joint or spinal implant infections are present.35,36 For adult patients hospitalized with osteomyelitis, parenteral followed by oral antibiotic therapy appears to be as effective as long-term parenteral therapy. Evidence suggests that oral antibiotics have similar cure rates and lower risks and costs compared with parenteral antibiotics.20,37,38 Treatment typically lasts four to six weeks, but comparisons of treatment duration have not been well studied.37

| Organism | Preferred regimens | Alternative regimens* |

|---|---|---|

| Anaerobes | Clindamycin, 600 mg IV every 6 hours Ticarcillin/clavulanate (Timentin), 3.1 g IV every 4 hours | Cefotetan (Cefotan), 2 g IV every 12 hours Metronidazole (Flagyl), 500 mg IV every 6 hours |

| Cutibacterium acnes (formerly known as Propionibacterium acnes) | Penicillin G, 2 to 4 million units IV every 4 hours | Ceftriaxone, 2 g IV every 24 hours |

| Enterobacteriaceae (e.g., Escherichia coli), quinolone resistant | Ticarcillin/clavulanate, 3.1 g IV every 4 hours Piperacillin/tazobactam (Zosyn), 3.375 g IV every 6 hours | Ceftriaxone (Rocephin), 2 g IV every 24 hours |

| Enterobacteriaceae, quinolone sensitive | Fluoroquinolone (e.g., ciprofloxacin, 400 mg IV every 8 to 12 hours) | Ceftriaxone, 2 g IV every 24 hours Ciprofloxacin, 750 mg orally every 12 hours Levofloxacin (Levaquin), 750 mg orally every 24 hours |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | Cefepime, 2 g IV every 8 to 12 hours, plus ciprofloxacin, 400 mg IV every 8 to 12 hours | Imipenem/cilastatin (Primaxin), 1 g IV every 8 hours, plus aminoglycoside |

| Piperacillin/tazobactam, 3.375 g IV every 6 hours, plus ciprofloxacin, 400 mg IV every 12 hours | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus, methicillin resistant | Vancomycin, 15 to 20 mg per kg per dose IV every 8 to 12 hours For patients allergic to vancomycin: Linezolid (Zyvox), 600 mg IV every 12 hours or Rifampin, 600 mg daily | Daptomycin (Cubicin), 6 mg per kg IV every 24 hours Linezolid, 600 mg IV or orally every 12 hours Clindamycin, 600 mg IV or orally every 8 hours Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, 3.5 to 4.0 mg per kg per dose or 2 double-strength tablets (for an 80-kg [176-lb] adult) IV or orally every 8 to 12 hours |

| S. aureus, methicillin sensitive | Nafcillin or oxacillin, 1 to 2 g IV every 4 hours Cefazolin, 1 to 1.5 g IV every 6 hours | Ceftriaxone, 2 g IV every 24 hours Vancomycin, 1 g IV every 12 hours |

| Streptococcus species | Penicillin G, 2 to 4 million units IV every 4 hours | Ceftriaxone, 2 g IV every 24 hours Clindamycin, 600 mg IV every 6 hours |

DEBRIDEMENT

Surgical bony debridement followed by drainage of any associated soft tissue abscess continues to be a mainstay of therapy, although there is no clear recommendation about which cases will require debridement.36 Debridement is typically indicated as part of the initial treatment in the presence of underlying orthopedic hardware and necrotic bone. Stabilization of the bone is an essential component of debridement and can decrease healing time and complications. Surgical debridement after antibiotic therapy shortens hospital stays, reduces medical costs, provides satisfactory infection control, and prevents complications of long-term systemic antibiotic use.39 Debridement can be supplemented with the placement of antibiotic-loaded collagen sponges, which has some evidence supporting improved outcomes.40 Hyperbaric oxygen therapy can be used as an adjunctive modality and may be particularly helpful in cases of chronic osteomyelitis.41

Special Considerations

When selecting treatment strategies for osteomyelitis, several groups of patients require special considerations, such as children and patients who have prosthetic joints, vertebral osteomyelitis, and diabetes. The treatment of these groups is beyond the scope of this article.

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Hatzenbuehler, et al.2

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms osteomyelitis, imaging, diagnosis, and treatment. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Also searched were the Cochrane database, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness (DARE), Dynamed, and Essential Evidence Plus. Search dates: August 11, 2020, and March 10, 2021.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Army Medical Department or the U.S. Army at large.