Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(6):580-588

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Nutrition support therapy is the delivery of formulated enteral or parenteral nutrients to restore nutritional status. Family physicians can provide nutrition support therapy to patients at risk of malnutrition when it would improve quality of life. The evidence for when to use nutrition support therapy is inconsistent and based mostly on low-quality studies. Family physicians should work with registered dietitian nutritionists to complete a comprehensive nutritional assessment for patients with acute or chronic conditions that put them at risk of malnutrition. When nutrition support therapy is required, enteral nutrition is preferred for a patient with a functioning gastrointestinal tract, even in patients who are critically ill. Parenteral nutrition has an increased risk of complications and should be administered only when enteral nutrition is contraindicated. Family physicians can use the Mifflin-St Jeor equation to calculate the resting metabolic rate, and they should consult with a registered dietitian nutritionist to determine total energy needs and select a nutritional formula. Patients receiving nutrition support therapy should be monitored for complications, including refeeding syndrome. Nutrition support therapy does not improve quality of life in patients with dementia. Clinicians should engage in shared decision-making with patients and caregivers about nutrition support in palliative and end-of-life care.

Nutrition support therapy is the delivery of formulated enteral or parenteral nutrients to maintain or restore nutritional status. Enteral nutrition (EN) support is the provision of nutrition using an enteral device inserted into the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Parenteral nutrition (PN) support is the provision of nutrition intravenously. The evidence for when to use nutrition support therapy is inconsistent and based mostly on low-quality studies. Family physicians can provide nutrition support therapy to patients at risk of malnutrition when it would improve quality of life. This article focuses on caring for adults who need nutrition support therapy, which generally occurs in the hospital setting.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Physicians should work with a registered dietitian nutritionist who uses the Nutrition Care Process framework to assess the need for nutrition support therapy in patients at risk of malnutrition.6 | C | Guidelines recommended using a standard process for assessing nutritional risk. |

| Consider initiating EN feedings within 24 hours of gastrointestinal surgery.13 | B | A systematic review of low-quality studies showed a decreased length of hospital stay, but no effect on other outcomes. |

| In nonsevere acute pancreatitis, initiate early oral feeding. If nutrition support therapy is needed, use EN over total PN.14,15 | A | A systematic review showed no harms of early feeding and a reduced length of stay; a systematic review showed that in patients needing nutrition support, EN significantly decreased morbidity and mortality compared with total PN. |

| Use EN over PN in patients with a functioning gastrointestinal tract.12 | B | A systematic review of low-quality studies showed that EN may have fewer serious adverse events than PN. |

| In critically ill patients who need nutrition support therapy, use EN instead of PN or a combination of the two.4,17–19 | A | A large randomized controlled trial and a systematic review of low-quality studies comparing EN and PN in critically ill patients showed no difference in 90-day mortality. However, using EN may result in fewer respiratory infections and shorter hospital stays, and it is more cost-effective. |

| Consider using high-carbohydrate, high-protein, low-fat EN in patients with burns on more than 10% of their total body surface area.25 | B | A systematic review of low-quality studies showed that using a high-carbohydrate, high-protein, low-fat EN formula may result in a lower incidence of pneumonia compared with use of a low-carbohydrate, high-protein, high-fat diet. |

| In patients with dementia, avoid tube feeding.32 | C | A nonsystematic review found no evidence that tube feeding improved outcomes. |

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not recommend percutaneous feeding tubes in patients with advanced dementia. | American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine |

| American Geriatrics Society | |

| Do not insert percutaneous feeding tubes in individuals with advanced dementia. Instead, offer oral assisted feedings. | American Medical Directors Association |

Patient Assessment

A nutrition screening and assessment are required to determine an individual's nutrition status and the potential need for nutrition support therapy.1–4 Malnutrition is a deficiency, excess, or imbalance in an individual's intake of energy or nutrients; in this article, malnutrition is defined as conditions related to undernutrition. Table 1 provides selected tools for screening and identifying individuals at risk of malnutrition.5 There is insufficient evidence for using one tool vs. another; therefore, physicians should select a tool based on the patient and treatment setting.

| Tool | Website |

|---|---|

| Community setting | |

| Malnutrition Universal Screening Toola,c,d | https://www.bapen.org.uk/screening-and-must/must-calculator |

| Inpatient setting/hospitalized patients | |

| Malnutrition Screening Toola,b | https://abbottnutrition.com/tools-for-patient-care/rd-toolkit |

| Nutritional Risk Screening 2002a,c,d | https://www.mdcalc.com/nutrition-risk-screening-2002-nrs-2002 |

| Short Nutritional Assessment Questionnairea,b | https://www.fightmalnutrition.eu/toolkits/hospital-screening |

| Older adults | |

| Mini Nutritional Assessment–Short Forma,b,d | https://www.mna-elderly.com/mna-forms |

| Modified Mini Nutritional Assessment–Short Forma,b,c,d |

If screening determines that a patient is at higher risk of malnutrition, then family physicians should work with a registered dietitian nutritionist who uses the Nutrition Care Process framework for assessment.6 This includes evaluating anthropometric measurements; biochemical data, medical tests, and procedures; food and nutrition history; nutrition-focused physical findings; and patient history.

To determine if patients are meeting energy needs, physicians can use body weight, height, and age, with additional energy needs included for activity and metabolic needs for specific medical problems.7–9 An average adult requires 25 to 30 kcals per kg of body weight and 1 to 2 g of protein per kg of body weight, but family physicians should use a predictive formula such as the Mifflin-St Jeor equation and consult with a registered dietitian nutritionist when possible (Table 2).7,9

| Estimating energy needs using the Mifflin-St Jeor equation* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Males | |||

| RMR† = 9.99 × weight (kg) + 6.25 × height (cm) − 4.92 × age + 5 | |||

| Females | |||

| RMR† = 9.99 × weight (kg) + 6.25 × height (cm) − 4.92 × age − 161 | |||

| Estimating protein needs | |||

| Condition | Protein in g (based on body weight in kg) | ||

| Healthy adult | 0.8 | ||

| Adults > 65 years | 1.0 | ||

| Bariatric | 1.0 to 1.5 (ideal body weight) | ||

| Chronic kidney disease (for hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis) | 1.2 to 1.5 | ||

| Chronic kidney disease (nondialysis) | 0.6 to 0.75 | ||

| Critical illness | 1.2 to 2.0 | ||

| Heart failure | 1.12 to 1.37 | ||

| Hepatic disease | 1.0 to 1.2 (dry weight) | ||

| 1.2 to 1.5 (dry weight malnourished) | |||

| Hepatitis or cirrhosis without encephalopathy | 0.8 to 1.0 | ||

| Obesity | 2.0 (ideal body weight for obese classes 1 and 2) | ||

| 2.5 (ideal body weight for obese classes 3 and 4) | |||

| Pressure injury | 1.2 to 1.5 | ||

| Respiratory disease | 1.2 to 1.6 (maintenance) | ||

| 1.6 to 2.0 (for repletion) | |||

| 2.0 (ideal body weight for BMI of 30 to 40 kg per m2) | |||

| 2.5 (ideal body weight for BMI > 40 kg per m2) | |||

| Estimating fluid needs | |||

| Method 1 (based on energy intake) 1 mL of fluid per kcal Method 2 (based on age weight [e.g., Holliday-Segar formula]) | Method 3 (based on nitrogen and energy intake) 1 mL per kcal + 100 mL and body per g of nitrogen Method 4 (based on total body surface area) 1,500 mL per m2 | ||

| Age (years) | Body weight | ||

| 16 to 30 | 35 to 40 mL per kg | ||

| 31 to 54 | 30 to 35 mL per kg | ||

| 55 to 65 | 30 mL per kg | ||

| > 65 | 25 mL per kg | ||

Indications for Nutrition Support Therapy

Universal indications for nutrition support are controversial because of the lack of good-quality studies with patient-oriented outcomes.10,11 A Cochrane review of low-quality studies found no evidence of a mortality benefit or an increase in harm with nutrition support.12 However, there is better evidence for nutrition support therapy in some GI conditions. A Cochrane review showed that early EN support after lower GI surgery decreased the length of hospital stay but had no effect on other outcomes; therefore, physicians should consider initiating EN within 24 hours of lower GI surgery.13 In nonsevere acute pancreatitis, physicians should initiate early oral feeding and use EN if nutrition support therapy is needed.14,15 Beyond these conditions, physicians should perform a nutritional assessment to decide if nutrition support is needed.

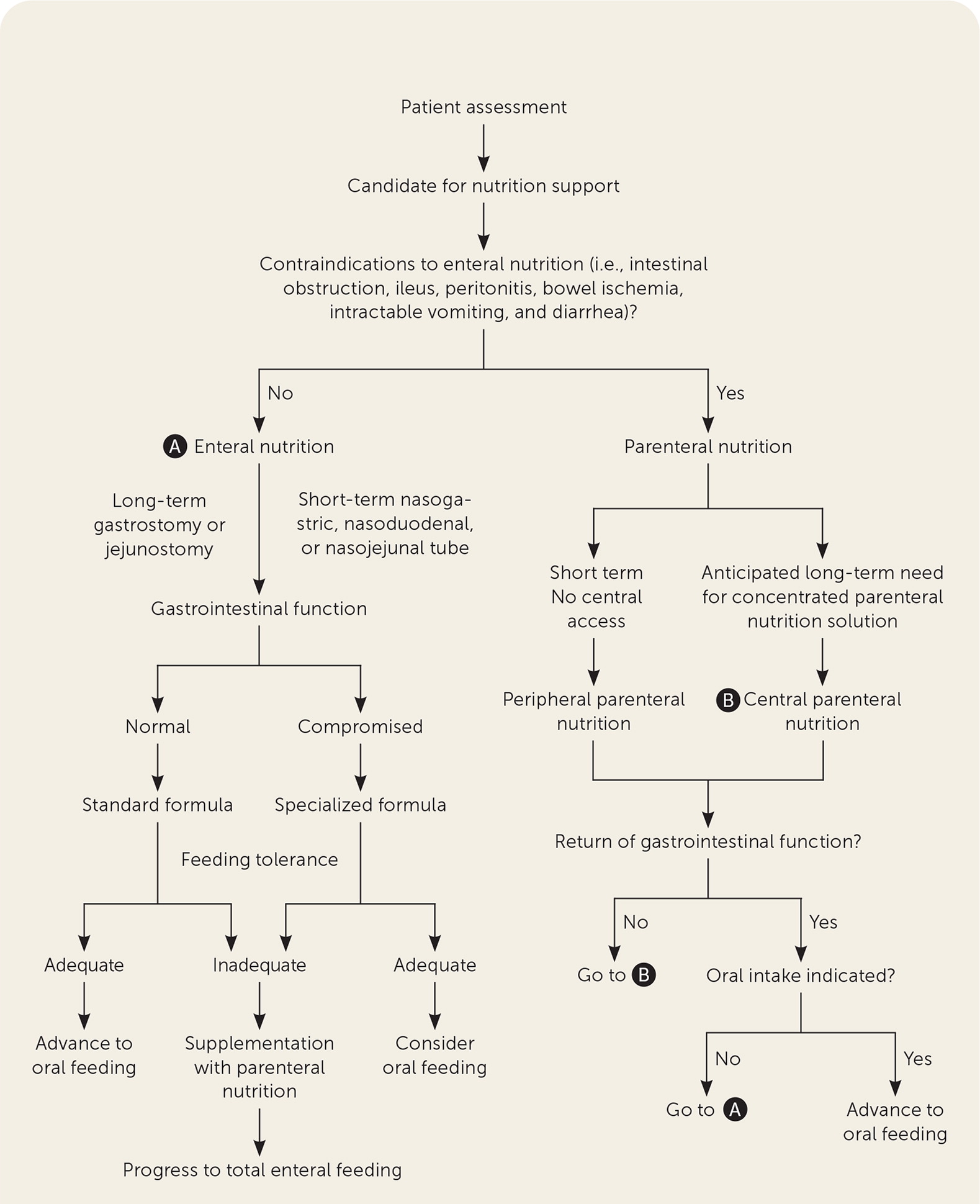

Patients may benefit from nutrition support if they are malnourished, at risk of malnutrition, or nourished but unable to meet estimated nutritional needs orally for more than five days.4 However, before initiating therapy, family physicians should determine goals for treatment, prognosis, and overall quality of life. Figure 1 provides an algorithm to help determine appropriateness and a potential route of administration for nutrition support.16

Enteral vs. Parenteral Nutrition Support

Research supports using EN over PN if an individual's GI system is functioning because EN generally has fewer adverse effects and may have better outcomes.1,4,12 Studies comparing EN and PN in critically ill patients did not show a difference in 90-day mortality; however, EN was associated with fewer respiratory infections and shorter hospital stays, and it was more cost-effective.4,17–19 Hospitals that use a nutrition support team to regulate the use of PN may have lower rates of inappropriate PN use.20

EN support may be provided to patients with a functional GI tract who are unable to consume enough food and fluids to meet estimated nutritional needs due to an impaired ability to ingest food (e.g., swallowing difficulty), changes in digestion or absorption, or alterations in nutritional requirements. EN support is not appropriate for patients who have severe GI malfunction (e.g., fistulas, ileus, bowel obstructions, uncontrolled vomiting, diarrhea) or are in a hypermetabolic state with poor enteral access (e.g., hemodynamic instability, multisystem organ failure).1 There is inconsistent evidence that starting EN early in critical illness has beneficial effects.21

PN support is indicated for individuals with severe GI malfunction or who are otherwise not good candidates for EN support therapy.1 PN support should not be used in individuals with a functioning GI tract unless the individual did not tolerate EN support therapy. Other relative contraindications to PN include individuals who are volume sensitive, those who are recreational or intravenous drug users, and patients expected to need less than seven days of nutrition support.1

Enteral Nutrition Support

ACCESS AND DELIVERY

EN support can be administered through a nasogastric, nasointestinal, gastrostomy, or jejunostomy tube. Short-term EN support is typically supplied via the nasal route, whereas longer-term EN is given through an enterostomy tube.1 The decision of how to administer EN support depends on multiple factors including gastric motility, gastric aspiration risk, GI anatomy, and the patient's medical condition. Gastric feeding more closely mimics normal intake physiology, is easier to administer, and allows for a larger volume and higher osmotic load than feeding into the small intestine. Postpyloric feeding may be beneficial in patients at high risk of aspiration, severe esophagitis, gastric dysmotility, gastric obstruction, recurrent emesis, or pancreatitis.22,23

Delivery of EN support can be accomplished through continuous, intermittent, or bolus feedings.1 Continuous feedings, given over 12 to 24 hours, or cyclic feedings, given over eight to 16 hours, are generally well tolerated, but require the use of a feeding pump. Intermittent feedings, given over 20 to 30 minutes, are provided to noncritically ill individuals who may not be able to tolerate bolus feedings. Bolus feedings are indicated for noncritically ill patients with an intact gag reflex and normal gastric function. Bolus feeding mimics normal feeding by providing a large volume of food into the stomach several times throughout the day without the need for a feeding pump.

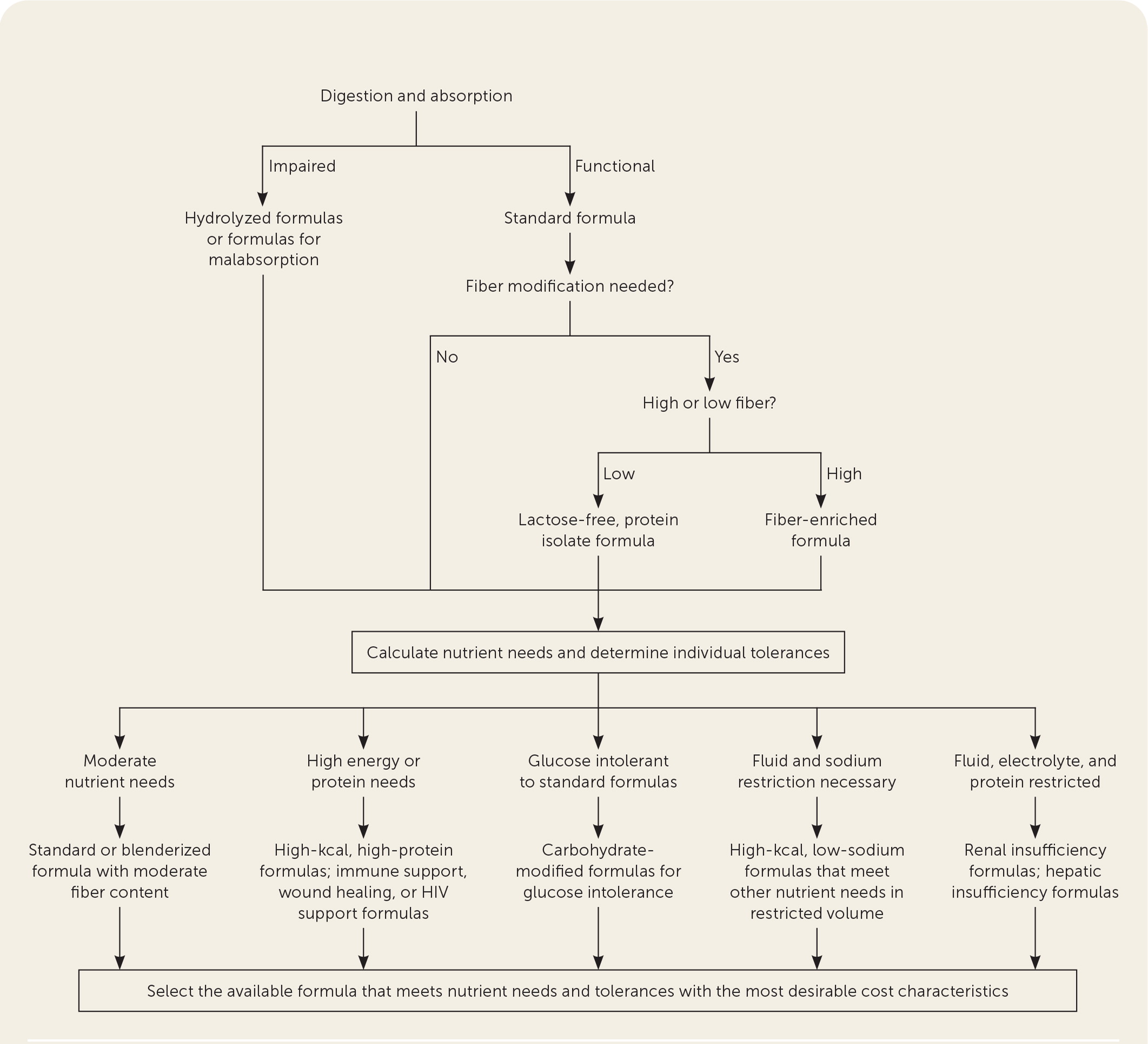

FORMULAS

EN support formulas can be divided into several categories: polymeric or intact formulas contain whole sources of macronutrients and are suitable for medically stable patients with a functioning GI tract. 24 Partially hydrolyzed or semi-elemental or elemental formulas contain peptides, free amino acids, or a combination of the two. These formulas are suitable for patients with malabsorption, pancreatic disease, or a recent GI surgery.1,24 Disease-specific formulas vary in their macro- and micro-nutrient content. A systematic review supported using high-carbohydrate, high-protein, low-fat formulas in patients with burns on more than 10% of their total body surface area to decrease the incidence of pneumonia.25 Blenderized tube feeding is a pureed mix of natural foods and can be used for a patient with an intact, functioning GI tract who may require long-term EN support. Modular products that contain only one nutrient (i.e., protein, carbohydrate, or lipid) may be added (via bolus) to help meet a patient's estimated needs if they are not met through the EN support formula alone. Figure 2 provides an approach to selecting appropriate EN formulas based on the patient's needs.26

Parenteral Nutrition Support

VENOUS ACCESS

PN support therapy can be provided via central or peripheral venous access. PN support administered via central venous access is referred to as total or central PN. PN support provided peripherally is referred to as peripheral PN. Peripheral PN support can be used in patients without fluid restriction and with an anticipated therapy duration of seven to 10 days.1 Providing nutrition through peripheral venous access is limited because formulations with osmolarity greater than 900 mOsm per L are poorly tolerated peripherally. Therefore, central or total PN support is usually needed to provide higher osmolarity formulations.

COMPOSITION AND FORMULATIONS

PN support is available as a three-in-one total nutrient admixture solution or more commonly as a two-in-one mixture of dextrose and amino acids, with fat emulsions infused as a separate solution.1 Many medications are incompatible with PN solutions (e.g., acyclovir, ceftriaxone) and should not be infused at the same time.

Dextrose, a carbohydrate providing 3.4 kcals per g, is available in concentrations ranging from 2.5% to 70%. The energy provided from carbohydrates in PN support is generally between 70% and 85% of the total daily nonprotein energy. To decrease the incidence of hyperglycemia, the amount of carbohydrate provided to adults should be 5 to 7 mg per kg per minute in patients who are not critically ill and 4 mg per kg per minute or less in those who are critically ill.1,2 To decrease the risk of thrombophlebitis when administering peripheral PN support, the carbohydrate concentration should not exceed 10%.

PN contains amino acids, instead of intact proteins, and is available in concentrations ranging from 3% to 20%. Different commercial solutions of amino acids vary in the amounts of essential and nonessential amino acids and are appropriate for certain conditions, such as hepatic failure.1 Excessive protein provided in PN support increases the metabolic load on the kidneys; therefore, renal function should be monitored.27

Lipids in PN support therapy contain intravenous fat emulsions and are most commonly provided as long-chain triglycerides; they can be a part of total nutrient admixture solutions or infused separately. Intravenous fat emulsions are available in concentrations of 10%, 20%, and 30%, providing 1.1, 2.0, and 2.9 to 3.0 kcals per mL, respectively. Intravenous fat emulsions are needed to prevent essential fatty acid deficiency. Smoflipid is a U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved alternative intravenous fat emulsion that contains fish oil, olive oil, and medium-chain triglycerides in addition to the long-chain triglycerides. Smoflipid has the potential to improve anti-inflammatory responses and decrease PN-associated hepatic disease.28 To avoid overwhelming the immune system, the formulation should not have more than 30% of its energy from fat.1

Minerals, vitamins, and other additives are incorporated into PN formulations to meet daily nutritional needs (eTable A). The requirements for minerals and vitamins in PN are significantly different from the dietary reference intakes because of differences in enteral absorption and bioavailability compared with direct intravenous administration.1 Multivitamin solutions are available with or without vitamin K for patients who are concurrently taking warfarin (Coumadin). Standard trace element solutions contain chromium, copper, manganese, zinc, and selenium. In patients with hepatic dysfunction, copper and manganese must be administered conservatively.1,2,29 In patients with increased small bowel losses, additional zinc may be required.1,2,29 Formulations do not routinely include iron because of stability issues.

| Electrolytes and minerals | |

| Acetate | As needed to maintain acid-base balance |

| Calcium | 10 to 15 mEq |

| Chloride | As needed to maintain acid-base balance |

| Magnesium | 8 to 20 mEq |

| Phosphorus | 20 to 40 mmol |

| Potassium | 1 to 2 mEq per kg |

| Sodium | 1 to 2 mEq per kg |

| Lipids | |

| Soybean oil–based emulsion | 1 g per kg |

| Multivitamin (10 mL for adults) | |

| Ascorbic acid (vitamin C) | 200 mg |

| Biotin | 60 mcg |

| Cyanocobalamin (vitamin B12) | 5 mcg |

| Folic acid | 600 mcg |

| Niacin (vitamin B3) | 40 mg |

| Pantothenic acid | 15 mg |

| Pyridoxine (vitamin B6) | 6 mg |

| Riboflavin (vitamin B2) | 3.6 mg |

| Thiamine (vitamin B1) | 6 mg |

| Vitamin A | 3,300 IU (1 mg) |

| Vitamin D | 200 IU (5 mcg) |

| Vitamin E | 10 IU (10 mg) |

| Vitamin K | 150 mcg |

| Trace mineral elements | |

| Chromium | < 1 mg |

| Copper | 0.3 to 0.5 mg |

| Manganese | 55 mcg |

| Selenium | 60 to 100 mcg |

| Zinc | 3 to 5 mg |

Monitoring and Complications

Patients receiving EN or PN support require close monitoring (Table 3).1 For individuals receiving EN support, family physicians should monitor tolerance to the food and feeding regimen (e.g., vomiting, altered bowel habits, abdominal distention, gastric residuals) and complications from enteral feeding tubes (e.g., nasal erosion, infection, migration, leakage). Family physicians should monitor patients receiving PN support for enteral intake, tolerance, and complications from parenteral lines (e.g., thrombophlebitis, infections). Any patient receiving nutrition support therapy should be evaluated for clinical signs of dehydration or volume overload, weight, and biochemical abnormalities. Biochemical assessment should include a baseline complete metabolic panel, complete blood count, triglycerides, magnesium, and phosphorus. For patients receiving EN support, family physicians should monitor laboratory values as needed based on the individual's clinical situation. For patients receiving PN support, family physicians should monitor laboratories daily until stable, and then at least weekly. Glucose levels should be monitored as required to achieve adequate glycemic control. For patients receiving long-term nutrition support therapy, family physicians should periodically measure iron, ferritin, zinc, copper, folate, vitamin B12, vitamin D, and vitamin K.

| Enteral nutritionParenteral nutrition | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Frequency | Parameter | Frequency |

| Anthropometrics | |||

| Body weight | Daily; 2 times per week when stable | Body weight | Daily; 2 to 3 times per week when stable |

| Biochemical | |||

| Calcium, magnesium, phosphorus | Daily; weekly when stable | Calcium, magnesium, phosphorus | 2 to 3 times per week; weekly when stable |

| Electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine | Daily; 2 to 3 times per week when stable | Electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine | Daily; 1 to 2 times per week when stable |

| Glucose | Patients with diabetes mellitus: every 6 hours; individualized frequency once stable | Glucose | 3 times per day until consistently < 200 mg per dL (11.10 mmol per L) |

| Patients without diabetes: daily; weekly when stable | |||

| Nitrogen balance | Weekly, if appropriate | Liver function tests | 2 to 3 times per week; weekly when stable |

| Triglycerides | Weekly | ||

| Complete blood count with differential | Weekly | ||

| Prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time | Weekly | ||

| Prealbumin or transferrin | Weekly | ||

| Nitrogen balance | As needed | ||

| Clinical | |||

| Gastric residuals | Every 4 to 6 hours when feeding into stomach | Vital signs: blood pressure, respirations, pulse | Daily; 3 times per week when stable |

| Intake and output | Daily | Intake and output | Daily |

| Stool output and consistency | Daily | Bowel function | As needed |

| Indirect calorimetry | As needed | ||

| Nutrition-focused physical examination | |||

| Abdominal examination if soft, firm, or distended | Daily | Hydration or fluid status: physical assessment of skin turgor, presence of edema, temperature; oral cavity for color, texture, moisture, or dryness | Daily; 3 times per week when stable |

| Signs or symptoms of dehydration | Daily | ||

| Signs or symptoms of edema | Daily | ||

Complications can occur with any form of nutrition support therapy; Table 4 outlines the most common complications.1 Complications associated with EN support include metabolic, GI, mechanical, and infectious.1,2 PN support can have metabolic and nonmetabolic complications. Metabolic complications include glucose abnormalities or hepatic dysfunction, which clinicians can decrease by monitoring and adjusting the composition and rates of infusion.1,2 Nonmetabolic complications include infectious or mechanical issues, which can be decreased with proper catheter care.1,2,30

| Complication | Factors to monitor |

|---|---|

| Enteral | |

| Gastrointestinal | |

| Abdominal distention | Excessive gas |

| Constipation | Decreased stool frequency |

| Diarrhea | Increased stool frequency or liquid consistency |

| Nausea or vomiting | Elevated gastric residuals |

| Infectious | |

| Contamination | Equipment (e.g., tube cleanliness) |

| Formula (e.g., expiration dates) | |

| Site cleanliness | |

| Mechanical | |

| Breakdown of tube site | Leakage from ostomy |

| Tube displacement or migration | Coiled or displaced tubes |

| Tube obstruction | Medication obstruction |

| Tube diameter | |

| Metabolic | |

| Edema or dehydration | Inadequate or excessive fluid intake, body weight |

| Hyper- or hypoglycemia | Serum glucose |

| Refeeding syndrome | Electrolytes (hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, hypophosphatemia) |

| Parenteral | |

| Biliary disease | Complete metabolic panel, magnesium, phosphorus, triglycerides, and vitamin D |

| Bone disease | |

| Electrolyte imbalances | |

| Hepatic disease | |

| Hyperglycemia | |

| Hyperlipidemia | |

| Rebound hypoglycemia | |

| Refeeding syndrome | |

| Hemodynamic instability | Vital signs |

| Infectious | Catheter cleanliness |

| Mechanical | Central venous access site and line |

| Thrombosis | Central venous line |

Another potential complication is refeeding syndrome, which is a dangerous condition resulting in many electrolyte abnormalities.1,2,29 Refeeding syndrome can occur during aggressive administration of nutrition support in patients who are malnourished.1,2,31 It is more common with PN support but can also occur with EN support. In patients at risk of refeeding syndrome (e.g., malnutrition, alcoholism, electrolyte abnormalities, anabolism), nutrition support should start at one-third or one-fourth of their nutritional needs and gradually increase over five to seven days.1

Nutrition Support Therapy in Palliative and End-of-Life Care

EN and PN support are specialized life-sustaining medical treatments that may impose discomfort and considerable risk. There is no specific evidence that tube feeding benefits patients with dementia.32 Nutrition support therapy is no different from other life-sustaining treatments for medicolegal issues.33 Family physicians should engage in shared decision-making with patients and caregivers when deciding when to initiate and withdraw nutrition support therapy.

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Kulick and Deen.34

Data Sources: The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Evidence Analysis Library, Essential Evidence Plus, and PubMed were searched using the key terms nutrition support, enteral nutrition, and parenteral nutrition. The search included guidelines, meta-analyses, and controlled trials. Search dates: April 3, 2020; June 2, 2021; and October 8, 2021.