Am Fam Physician. 2022;105(2):162-167

Patient information: See related handout on this maturity-onset diabetes of the young, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: Dr. Kant does not have a formal relationship with any commercial company to disclose, but a public database revealed food and beverage listings for several drugs related to the topic of this manuscript. None of these involved cash payments and are not considered a violation of AFP's conflict-of-interest policy. Drs. Davis and Verma have no relevant financial relationships.

Maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) is a non–insulin-dependent form of diabetes mellitus that is usually diagnosed in young adulthood. MODY is most often an autosomal dominant disease and is divided into subtypes (MODY1 to MODY14) based on the causative genetic mutation. Subtypes 1 to 3 account for 95% of cases. MODY is often misdiagnosed as type 1 or 2 diabetes and should be suspected in nonobese patients who have diabetes that was diagnosed at a young age (younger than 30 years) and a strong family history of diabetes. Unlike those with type 1 diabetes, patients with MODY have preserved pancreatic beta-cell function three to five years after diagnosis, as evidenced by detectable serum C-peptide levels with a serum glucose level greater than 144 mg per dL and no laboratory evidence of pancreatic beta-cell autoimmunity. Patients with MODY1 and MODY3 have progressive hyperglycemia and vascular complication rates similar to patients with types 1 and 2 diabetes. Lifestyle modification including a low-carbohydrate diet should be the first-line treatment for MODY1 and MODY3. Sulfonylureas are the preferred pharmacologic therapy based on pathophysiologic reasoning, although clinical trials are lacking. Patients with MODY2 have mild stable fasting hyperglycemia with low risk of diabetes-related complications and generally do not require treatment, except in pregnancy. Pregnant patients with MODY may require insulin therapy and additional fetal monitoring for macrosomia.

Maturity-onset diabetes of the young (MODY) is an underrecognized type of diabetes mellitus that is usually diagnosed in young adulthood. Advances in genetic testing have led to the discovery of more subtypes of the disease. This article provides a summary of the most common subtypes of MODY to help primary care clinicians distinguish the condition from types 1 and 2 diabetes.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| MODY should be considered in nonobese patients who have diabetes mellitus that was diagnosed at a young age (younger than 30 years), preserved pancreatic beta-cell function, lack of pancreatic beta-cell autoimmunity, and a strong family history of diabetes.1 | C | Consensus, expert opinion |

| Sulfonylureas are the preferred pharmacologic therapy for hyperglycemia in MODY1 and MODY3.3,4 | C | Consensus, expert opinion |

| Pharmacologic treatment of hyperglycemia is not required for MODY2 because the risk of vascular complications is low and patients are asymptomatic.3,4 | C | Consensus, expert opinion |

Epidemiology and Genetics

MODY accounts for approximately 1% to 5% of diabetes cases.1

It is most often an autosomal dominant disease, with 50% of offspring affected. In the most common subtype (MODY3), more than 95% of people with the mutation will develop diabetes, most by 25 years of age.2

At least 14 genes have been found to cause MODY. The glucokinase (GCK), hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 alpha (HNF1A), and HNF4A genes are implicated in approximately 95% of cases.3 This article focuses on subtypes 1 to 3, which are caused by these mutations (Table 13–8).

| Subtype | Gene mutation | Prominent features |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | HNF4A | Progressive symptomatic diabetes mellitus with significant glucose intolerance Prone to diabetes-related vascular complications Associated with fetal macrosomia and neonatal hypoglycemia Treatment: sensitive to sulfonylureas; meglitinide and glucagon-like peptide 1 agonist may be considered |

| 2 | GCK | Asymptomatic with stable mild fasting hyperglycemia and A1C levels ranging from 5.7% to 7.5% Low risk of diabetes-related vascular complications Pregnancy: use of insulin determined by mutation status of mother and fetus and/or evidence of accelerated fetal growth on ultrasonography Treatment: not required except in pregnancy |

| 3 | HNF1A | Most common subtype (30% to 50%) Progressive symptomatic diabetes with significant glucose intolerance Prone to diabetes-related vascular complications Postprandial glycosuria develops before the onset of diabetes HNF1A mutation in the fetus does not affect birth weight Treatment: sensitive to sulfonylureas; meglitinide and glucagon-like peptide 1 agonist may be considered |

Diagnosis

Up to 80% of MODY cases are misdiagnosed as type 1 or 2 diabetes.9

MODY should be considered in nonobese patients who have diabetes that was diagnosed at a young age (younger than 30 years), preserved pancreatic beta-cell function, lack of pancreatic beta-cell autoimmunity, and a strong family history of diabetes.1

Accurate diagnosis of MODY guides treatment. Based on the pathophysiology of the disease, sulfonylureas are thought to be the most effective pharmacologic therapy for the most common subtypes.3,4,10 However, there is no evidence from randomized trials showing that early diagnosis and appropriate therapy improve patient-oriented outcomes.

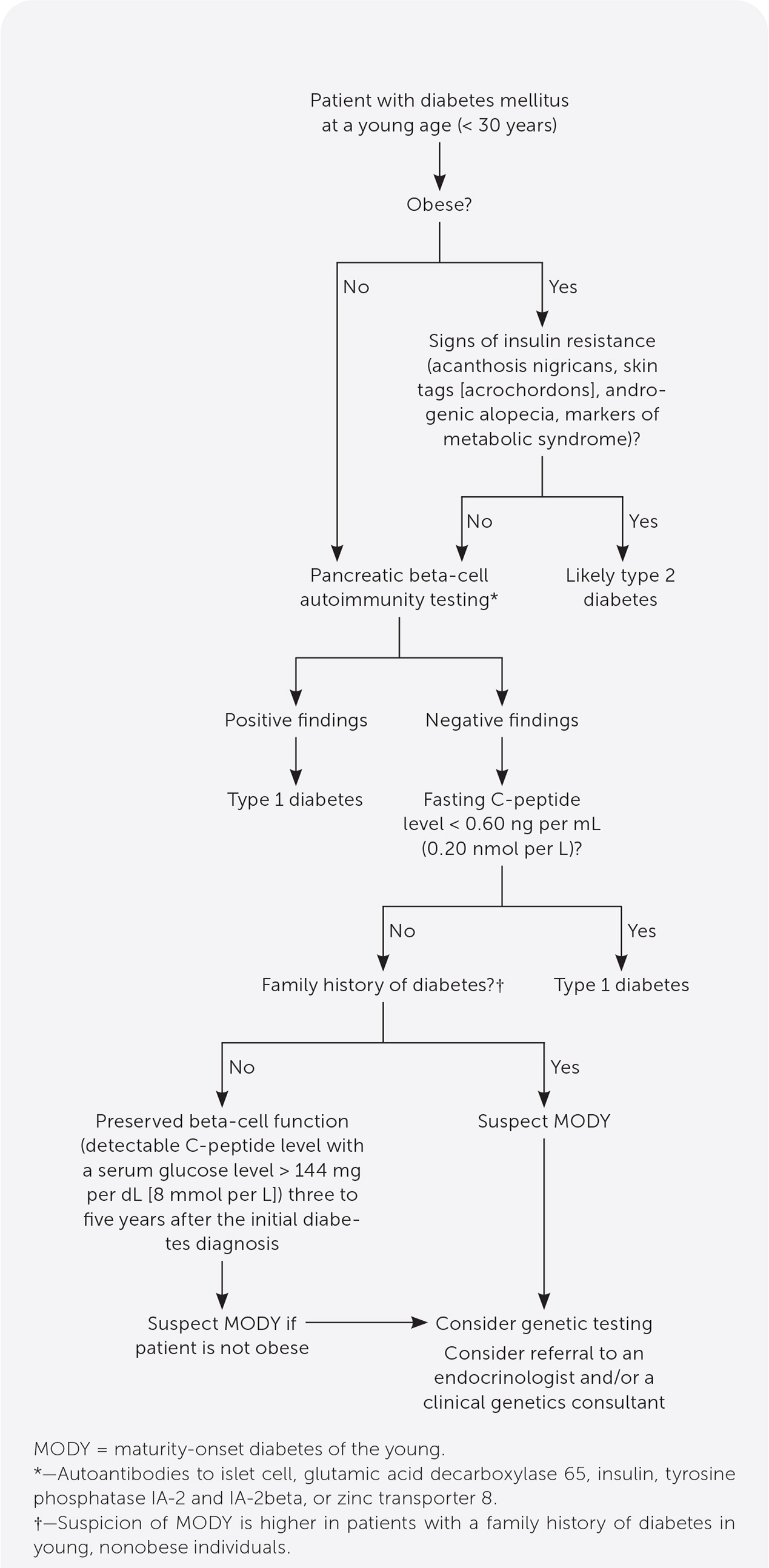

Commercially available genetic testing can confirm the diagnosis of MODY. Targeted genetic testing is appropriate because of high cost (Figure 1). Referral to an endocrinologist and/or a clinical genetics consultant should be considered when clinical suspicion for MODY is high.

TYPE 1 DIABETES VS. MODY

The pathogenesis of MODY does not involve pancreatic beta-cell autoimmunity.

Type 1 diabetes is caused by autoimmune beta-cell destruction, usually leading to absolute insulin deficiency. A laboratory test confirming autoantibodies to islet cells, glutamic acid decarboxylase 65, insulin, tyrosine phosphatase IA-2 and IA-2beta, or zinc transporter 8 is diagnostic for type 1 diabetes.11

Adding the zinc transporter 8 autoantibody to commercially available beta-cell autoantibody test combinations has increased autoimmunity detection rates for new-onset type 1 diabetes to 96% to 98%.12,13

Clinicians may consider the cost-saving approach of checking glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 and tyrosine phosphatase IA-2 at the initial assessment and testing for other autoantibodies only if both are negative.14

Repeat autoantibody testing after a few years in patients with autoantibody-negative type 1 diabetes has been shown to improve detection of beta-cell autoimmunity.15

Patients with autoantibody-negative type 1 diabetes are more likely to have clinical characteristics associated with other diabetes subtypes (e.g., older age, higher body mass index, family history of diabetes). A subset of these patients may have monogenic or type 2 diabetes.16

Levels of C-peptide, a product of the insulin prohormone, is used to assess pancreatic beta-cell function and insulin secretion. In healthy people, fasting C-peptide levels range from 0.9 to 1.8 ng per mL (0.3 to 0.6 nmol per L) and increase to 3 to 9 ng per mL (1 to 3 nmol per L) after meals.17 A fasting C-peptide level of less than 0.60 ng per mL (0.20 nmol per L) represents insulin deficiency and is associated with type 1 diabetes.17

A detectable serum C-peptide level with a serum glucose level greater than 144 mg per dL (8 mmol per L) three to five years after diagnosis is unusual in a patient with type 1 diabetes and favors the diagnosis of MODY.4

TYPE 2 DIABETES VS. MODY

The pathophysiology of MODY involves impaired insulin secretion, whereas type 2 diabetes is a heterogeneous disease characterized by insulin resistance and a progressive loss of beta-cell function.11

Clues that a patient presumed to have type 2 diabetes may actually have MODY include a lack of response to metformin, a larger drop in serum glucose level with sulfonylureas, and greater sensitivity to insulin.10

Although definitive guidelines are lacking, testing for MODY can be considered in a patient younger than 30 years who has diabetes and:

○ Is not obese

○ Lacks signs of insulin resistance such as acanthosis nigricans, skin tags, androgenic alopecia, or markers of metabolic syndrome

○ Lacks pancreatic beta-cell autoantibodies

○ Has a fasting C-peptide level greater than 0.60 ng per mL

○ Has a family history of diabetes in young, nonobese family members10

FEATURES OF MODY1 AND MODY3

MODY1 and MODY3 are caused by mutations in transcription factors (HNF4A and HNF1A, respectively). This results in impaired insulin secretion from defective beta-cell signaling in response to glucose.5 These patients have glucose intolerance and may have normal fasting serum glucose levels in the early stages of the disease.

Patients with MODY3 usually develop postprandial glycosuria before the onset of diabetes.6

Like patients with types 1 and 2 diabetes, patients with MODY1 and MODY3 are thought to develop associated micro- and macrovascular complications caused by suboptimal glycemic control.3

FEATURES OF MODY2

MODY2 is caused by mutations in the GCK gene, resulting in a higher glucose set point for insulin secretion.5 In contrast to those with other subtypes, patients with MODY2 regulate insulin secretion adequately, but higher serum glucose levels are needed to induce insulin secretion.4,11

Patients with MODY2 are typically asymptomatic and may have stable mild fasting hyperglycemia (100 to 145 mg per dL [5.55 to 8.05 mmol per L]) for years, with A1C levels ranging from 5.7% to 7.5%.18,19

Unlike in MODY1 and MODY3, patients with MODY2 usually do not have significant postprandial hyperglycemia.18

MODY2 is not associated with a higher incidence of vascular complications.3,20

Patients with MODY2 are at risk of developing concurrent type 2 diabetes later in life, with prevalence similar to that in the general population.21

Treatment

MODY1 AND MODY3

There are limited data on what A1C goals are associated with the best outcomes for patients with MODY1 and MODY3. Because these patients are thought to be susceptible to micro-and macrovascular complications, it is reasonable to individualize A1C goals based on patient characteristics (e.g., comorbidities, life expectancy, risks associated with hypoglycemia), as recommended by American Diabetes Association guidelines for patients with types 1 and 2 diabetes.22

Lifestyle modification including a low-carbohydrate diet should be first-line therapy because MODY1 and MODY3 are predominantly associated with glucose intolerance.

If glycemic control worsens, sulfonylureas are the recommended pharmacologic therapy because these drugs bypass the defective glucose-mediated insulin secretion associated with HNF1A and HNF4A mutations.3,4

Patients with MODY3 are four times more responsive to sulfonylureas than patients with type 2 diabetes and are therefore at higher risk of hypoglycemia when using these drugs.10

Sulfonylureas should be started at one-fourth of the typical starting dose to avoid hypoglycemia, then slowly titrated to achieve optimal glycemic control.3,4

Although glucose-induced insulin secretion may decline over time, most patients remain responsive to sulfonylureas for decades.23

Meglitinides may be considered instead of sulfonylureas to treat postprandial hyperglycemia if sulfonylurea use is complicated by frequent hypoglycemic events.7

A small double-blind, randomized, crossover trial compared liraglutide (Victoza), a glucagon-like peptide 1 agonist, with glimepiride (Amaryl), a sulfonylurea. Patients taking liraglutide had similar glycemic control as those taking glimepiride but much lower risk of hypoglycemia. Liraglutide may be considered in patients who are obese or with high rates of hypoglycemia.8

Limited data suggest that dipeptidyl-peptidase 4 inhibitors and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors may also be effective, but additional studies are needed.24,25

Because MODY is associated with impaired insulin secretion and minimal or no defects in insulin action, metformin is not a preferred pharmacologic agent.

MODY2

Special Considerations for Pregnant Patients

MODY may be first discovered when screening for gestational diabetes during pregnancy. The prevalence of MODY in patients with gestational diabetes is estimated at 1% to 6%.26,27

There are no guidelines to assist in determining which patients with gestational diabetes should be tested for MODY.

A diagnosis of MODY may be considered in pregnant patients younger than 25 years with a normal prepregnancy body mass index; a history of previous gestational diabetes; and a family history of diabetes, gestational diabetes, or fasting hyperglycemia greater than 99 mg per dL (5.5 mmol per L).28,29

There is a lack of high-quality evidence to guide MODY treatment in pregnancy.

Glyburide is the only sulfonylurea recommended for use during pregnancy because it has been studied most extensively.30

However, glyburide use in patients with gestational diabetes is associated with more than a twofold increased risk of macrosomia and neonatal hypoglycemia compared with insulin use. Insulin is therefore the preferred agent in pregnant patients with MODY1 and MODY3, particularly in the third trimester.30,31

Experts recommend switching from a sulfonylurea to insulin before conception, or during the second trimester in patients with excellent glycemic control.30

The risk of macrosomia depends on the MODY subtype of the mother and fetus. If mother and fetus have MODY1, there is an increased risk of macrosomia.32 In contrast, if mother and fetus have MODY2, there is no increased risk.3 MODY3 is not a risk factor for macrosomia, regardless of mutation status of the fetus.3,32

Pregnant patients with MODY2 are treated based on mutation status of the fetus. If mother and fetus have MODY2, no treatment is needed (both have the same glucose set point and therefore no increased risk of macrosomia). If the mother has MODY2 but the fetus does not, treatment with insulin is recommended to control maternal hyperglycemia and decrease the risk of macrosomia.3

Prolonged neonatal hypoglycemia may occur in neonates born to mothers with MODY1, and monitoring is recommended for at least 48 hours.30

Diagnosis of MODY in pregnancy allows for the opportunity to offer genetic testing for the infant in the newborn period.30

Data Sources: PubMed searches were performed using combinations of the search terms MODY and GDM, MODY and pregnancy, MODY and genetic counseling, and monogenic diabetes. We included randomized controlled trials, meta-analyses, and reviews published within the previous five years. Search dates: December 2020, January 2021, and November 2021.