Am Fam Physician. 2022;105(3):289-298

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Parathyroid disorders are most often identified incidentally by abnormalities in serum calcium levels when screening for renal or bone disease or other conditions. Parathyroid hormone, which is released by the parathyroid glands primarily in response to low calcium levels, stimulates osteoclastic bone resorption and serum calcium elevation, reduces renal calcium clearance, and stimulates intestinal calcium absorption through synthesis of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D. Primary hyperparathyroidism, in which calcium levels are elevated without appropriate suppression of parathyroid hormone levels, is the most common cause of hypercalcemia and is often managed surgically. Indications for parathyroidectomy in primary hyperparathyroidism include presence of symptoms, age 50 years or younger, serum calcium level more than 1 mg per dL above the upper limit of normal, osteoporosis, creatinine clearance less than 60 mL per minute per 1.73 m2, nephrolithiasis, nephrocalcinosis, and hypercalciuria. Secondary hyperparathyroidism is caused by alterations in calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D regulation that result in elevated parathyroid hormone levels. It most commonly occurs with chronic kidney disease and vitamin D deficiency, and less commonly with gastrointestinal conditions that impair calcium absorption. Secondary hyperparathyroidism can be managed with calcium and vitamin D replacement and reduction of high phosphate levels. There is limited evidence for the use of calcimimetics and vitamin D analogues for persistently elevated parathyroid hormone levels. Hypoparathyroidism, which is most commonly caused by iatrogenic surgical destruction of the parathyroid glands, is less common and results in hypocalcemia. Multiple endocrine neoplasia types 1 and 2A are rare familial syndromes that can result in primary hyperparathyroidism and warrant genetic testing of family members, whereas parathyroid cancer is a rare finding in patients with hyperparathyroidism.

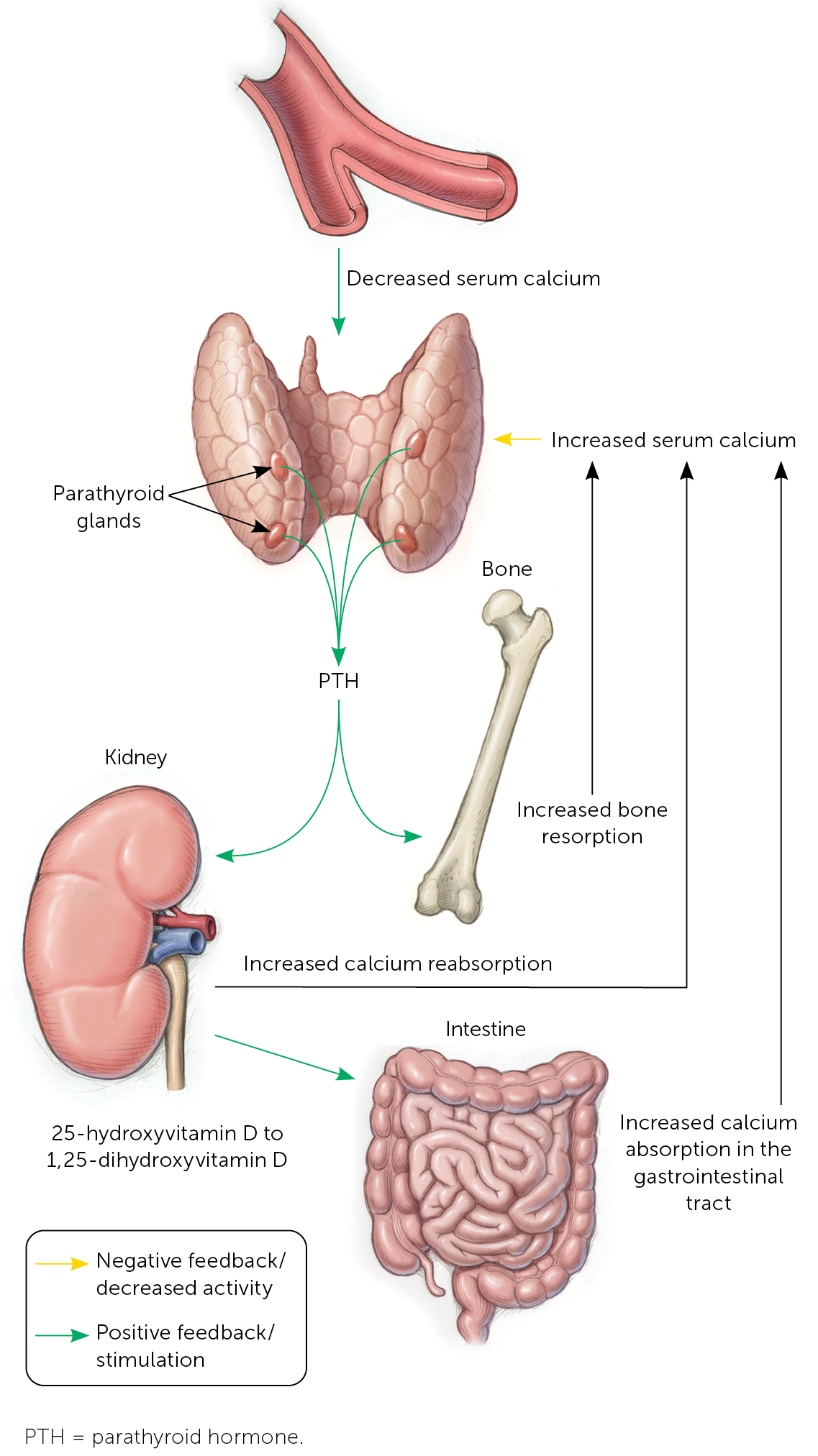

The parathyroid glands typically lie adjacent to the thyroid gland, although they are occasionally located in the superior mediastinum.1 Parathyroid glands regulate serum calcium in response to abnormal levels. When the extracellular calcium-sensing receptor (CASR) on parathyroid cells detects low serum calcium levels, one or more of the parathyroid glands release parathyroid hormone (PTH), an 84–amino acid peptide.1 PTH stimulates osteoclasts to resorb bone and mobilize calcium into the blood, reduces renal calcium clearance, and stimulates intestinal calcium absorption through synthesis of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D (Figure 1).2 Conversely, high calcium levels drive PTH suppression, with hypermagnesemia and 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D also inhibiting the production and release of PTH. Parathyroid disorders can be primary or secondary.

Initial Approach to Calcium Abnormalities

Parathyroid disorders are most often identified incidentally by abnormalities in serum calcium levels when screening for renal or bone disease or other conditions.1,3 Once a calcium abnormality has been identified, the evaluation should include a systematic search for signs and symptoms associated with abnormal calcium levels (Table 1).1,2,4–6 A history should include dietary intake of calcium and phosphorus, medications that increase serum calcium levels (Table 21,2,4–6), supplements that contain calcium, and family history of endocrine disorders. A patient history of conditions such as fractures, pancreatitis, and nephrolithiasis may indicate or contribute to abnormal calcium levels.

| Organ system | Hypercalcemia | Hypocalcemia |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular | Arrhythmias, bradycardia, hypertension, palpitations, prolonged PR interval, shortened QT interval | Arrhythmias, dyspnea, heart failure, hypotension, palpitations, prolonged QT interval, syncope, torsades de pointes |

| Gastrointestinal | Abdominal pain, anorexia, constipation, dyspepsia, epigastric pain, nausea, pancreatitis, vomiting | Abdominal pain |

| Musculoskeletal | Arthralgias, bone pain, fractures, myalgias | Muscle spasms |

| Neurologic | Confusion, delirium, headache, impaired concentration, impaired vision, lethargy, memory loss, sleep disturbance | Acute: Chvostek sign,* circumoral numbness, headache, impaired vision, seizures, tetany, Trousseau sign† Chronic: dementia, parkinsonism |

| Psychiatric | Anxiety, depression, emotional instability | Anxiety, depression |

| Pulmonary | — | Bronchospasm, laryngospasm, wheezing |

| Renal | Polydipsia, polyuria, renal colic, renal failure | — |

| PTH dependent Genetic disorders: familial hyperparathyroidism, familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia, hyperparathyroidism–jaw tumor syndrome, multiple endocrine neoplasia Medications: lithium Primary hyperparathyroidism Tertiary hyperparathyroidism* |

| PTH independent Cancer: humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy (mediated by PTH-related peptide), osteolytic metastases (e.g., multiple myeloma) Excess vitamin D Endogenous sources: Williams syndrome, granulomatous diseases such as sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, histoplasmosis, or coccidioidomycosis Exogenous sources: vitamin D supplements or analogues Medications: thiazides, theophylline, vitamin A, synthetic PTH (teriparatide [Forteo], abaloparatide [Tymlos]), calcium (milk-alkali syndrome) Other endocrine disorders: thyrotoxicosis, adrenal insufficiency, pheochromocytoma Renal failure (acute or chronic) |

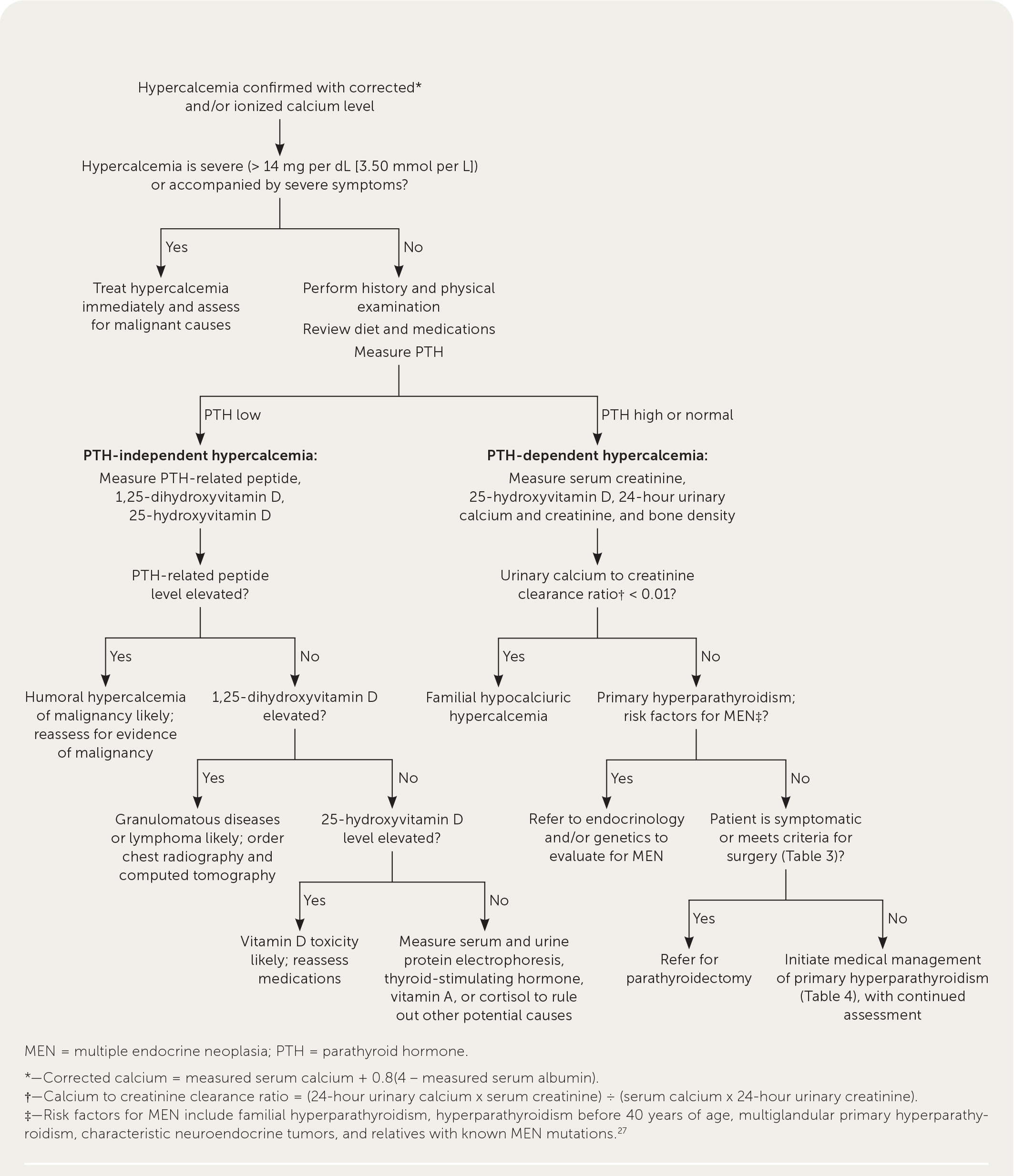

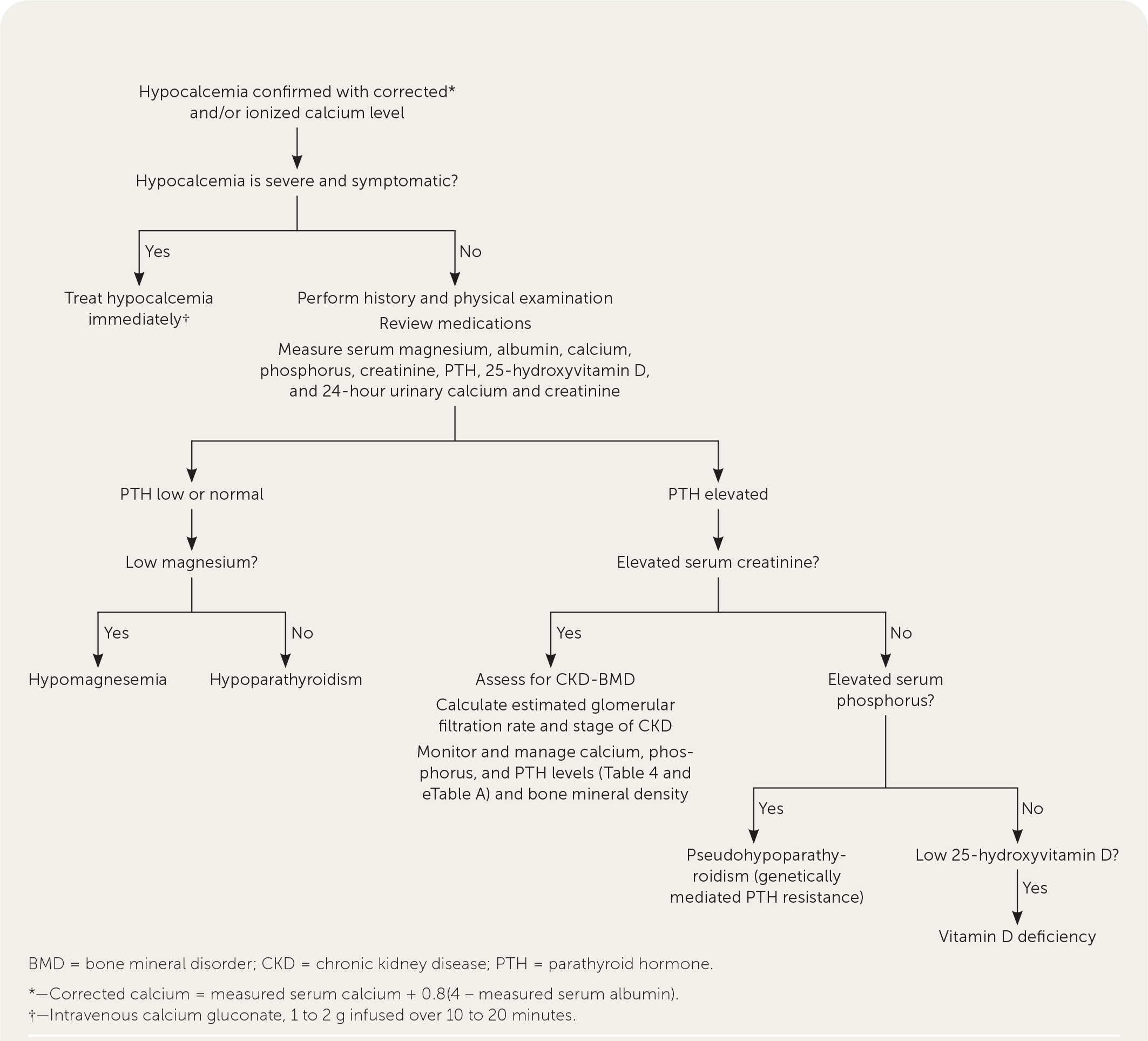

Initial laboratory testing (Figure 21,2,4–6 and Figure 37–11) can be used to identify potential etiologies of parathyroid disorders that affect calcium levels. Primary hyperparathyroidism and malignancy are the most common causes of hypercalcemia.4 Additional causes are listed in Table 2.1,2,4–6 Humoral hypercalcemia of malignancy, a paraneoplastic syndrome mediated by PTH-related peptide, should be considered in patients with low PTH levels, rapid onset of symptoms, and other signs and symptoms of malignancy (e.g., weight loss, fatigue, loss of appetite, night sweats). It is most often associated with squamous cell carcinoma and solid tumors of the lung, breast, esophagus, skin, cervix, and kidney.4 Vitamin D deficiency is the most common cause of hypocalcemia.5

Severe symptomatic hypercalcemia (serum calcium level greater than 14 mg per dL [3.50 mmol per L]) should be managed acutely with intravenous fluids, bisphosphonates, calcitonin, denosumab, or dialysis.6 Severe symptomatic hypocalcemia, which can present acutely with carpopedal spasm, tetany, seizures, and a prolonged QT interval, should be managed with intravenous calcium gluconate while the cause is being determined.12

Hyperparathyroidism

PRIMARY

Primary hyperparathyroidism is a common condition and the most common cause of hyperparathyroidism and mild hypercalcemia.1,13 In primary hyperparathyroidism, calcium levels are usually elevated without appropriate suppression of PTH levels, which can be normal or high.13 However, in normocalcemic cases, calcium levels can be normal with elevated PTH levels, which may be encountered incidentally when screening for bone and renal disorders. In nations with readily accessible laboratory services, primary hyperparathyroidism is most often identified in asymptomatic individuals as an incidental finding of hypercalcemia on routine laboratory testing.

Comprehensive evaluation of hypercalcemia (Figure 21,2,4–6) to identify primary hyperparathyroidism should begin with symptom assessment and laboratory testing, including measurements of serum total or ionized calcium, albumin (for calcium correction), PTH, serum creatinine, 25-hydroxyvitamin D, and 24-hour urinary calcium and creatinine levels (to distinguish from hypocalciuric hypercalcemia). Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry is also recommended.13,16 Parathyroid imaging is not needed to diagnose primary hyperparathyroidism but may be helpful for perioperative management.15

Familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia is a rare, autosomal dominant disorder that presents with abnormally high levels of calcium in the blood, low urinary calcium excretion, and normal or slightly elevated PTH levels. Familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia generally does not require treatment, including surgery.13,17 Genetic counseling to identify the approximately 10% of patients with a CASR gene mutation is recommended for patients with primary hyperparathyroidism who are younger than 40 years or have a suspected familial cause (familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia), clinical findings suspicious for MEN1, or multiglandular disease.16

Indications for parathyroidectomy in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism include the presence of symptoms, age 50 years or younger, serum calcium level more than 1 mg per dL (0.25 mmol per L) above the upper limit of normal, osteoporosis, creatinine clearance less than 60 mL per minute per 1.73 m2 (1.00 mL per second per m2), nephrolithiasis, nephrocalcinosis, and hypercalciuria (Table 3).13,15–17 Patients who desire surgery and do not have contraindications may also be considered for parathyroidectomy. Increasing evidence regarding the benefits and risks of operative management has expanded the number of asymptomatic patients who are recommended for surgery.

| Asymptomatic primary hyperparathyroidism and any of the following: 50 years or younger at diagnosis Serum calcium level > 1 mg per dL (0.25 mmol per L) above the upper limit of normal Osteoporosis (T-score < −2.5), fragility fracture, or evidence of vertebral compression fracture on spinal imaging Creatinine clearance < 60 mL per minute per 1.73 m2 (1.00 mL per second per m2) or other renal involvement, including silent nephrolithiasis on imaging, nephrocalcinosis, or hypercalciuria (24-hour urinary calcium level > 400 mg per dL) Patients who desire surgery and have no medical contraindications Symptomatic hypercalcemia |

Parathyroidectomy has been shown to normalize PTH and calcium levels, decrease nephrolithiasis, reduce renal function deterioration, and improve bone mineral density.16–19 Postoperative hypoparathyroidism is a rare complication (0% to 3.6%).15 Risks of untreated primary hyperparathyroidism include increased mortality, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, renal failure, nephrolithiasis, and reduced bone mineral density.19,20 The effects of nontreatment on neurocognitive symptoms are less clear.

Asymptomatic patients who are not surgical candidates should be monitored to identify those who may benefit from risk reduction and medical management of the complications of untreated primary hyperparathyroidism. This surveillance includes serum calcium, creatinine, and estimated glomerular filtration rate measurements annually and bone density evaluation every one to two years.16 Annual renal imaging and 24-hour urine collection are also indicated in patients with a history of renal calculi.16

All patients should be encouraged to maintain adequate hydration to reduce the risk of nephrolithiasis, maintain adequate physical activity to minimize bone resorption, and avoid medications that increase hypercalcemia (e.g., thiazides, lithium). Maintaining adequate dietary calcium intake (1,000 mg per day) and vitamin D intake (400 to 800 IU per day) to keep 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels at 20 or 30 ng per mL (49.92 or 74.88 nmol per L) or higher helps avoid further increases in PTH level.13,16

| Medication | Primary indication | Effects | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bone mineral density | Calcium | PTH | ||

| Bisphosphonates* | ||||

| Alendronate (Fosamax) Pamidronate Risedronate (Actonel) Zoledronic acid (intravenous; Reclast) | Increase bone mineral density | Increased, no fracture data | Serum: unchanged | Unchanged |

| Calcimimetics | ||||

| Cinacalcet (Sensipar) Etelcalcetide (Parsabiv) Evocalcet (not available in the United States) | Reduce serum calcium | Unchanged | Serum: decreased | Decreased |

| Hormone therapy (postmenopause) | ||||

| Estrogen Selective estrogen receptor modulators | Reduce menopausal symptoms | Increased, no fracture data | Serum: decreased | Unchanged |

| Monoclonal antibodies | ||||

| Denosumab | Increase bone mineral density | Increased | Serum: decreased | Unchanged or increased |

| Thiazide diuretics† | ||||

| Chlorthalidone Hydrochlorothiazide | Reduction of urinary calcium can reduce risk of nephrolithiasis | Increased | Serum: increased or unchanged Urine: decreased | Decreased |

| Vitamin D | ||||

| Cholecalciferol (D3) Ergocalciferol (D2) | Increase vitamin D | Increased | Serum and urine: increased or unchanged | Decreased |

SECONDARY

Secondary hyperparathyroidism is a result of alterations in calcium, phosphate, and vitamin D regulation from nonparathyroid causes that lead to elevated PTH levels. It most commonly occurs with chronic kidney disease (CKD) and vitamin D deficiency and less commonly with gastrointestinal conditions that impair calcium absorption.7 Laboratory testing to evaluate for potential causes and management should include measurement of serum PTH, creatinine, calcium, phosphate, albumin, alkaline phosphatase, and 25-hydroxyvitamin D.8 Management of secondary hyperparathyroidism is important for prevention of bone and cardiovascular diseases.8

Family physicians commonly care for patients with renal impairment who are not undergoing dialysis and play an important role in laboratory monitoring (eTable A) and initial management of CKD–bone mineral disorder (BMD), which is a disorder of mineral and bone metabolism as a result of renal disease. In patients with CKD stage 3a to 5, bone density measurement can predict fracture risk.8 Initial treatment of secondary hyperparathyroidism (Table 58) is focused on treating underlying causes and can include calcium replacement, vita-min D replacement, and reduction of high phosphate levels, with the goal of avoiding severe hyperphosphatemia and hypercalcemia, which have been associated with increased mortality.8

| CKD stage | eGFR (mL per minute) | Serum laboratory tests | Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3a or 3b | 30 to 59 | Calcium, phosphorus | At baseline and then every 6 to 12 months |

| PTH | At baseline and then repeat based on baseline level and CKD progression | ||

| 4 | 15 to 29 | Calcium, phosphorus | Every 3 to 6 months |

| PTH | Every 6 to 12 months | ||

| Alkaline phosphatase | Every 12 months, or more often based on baseline level | ||

| 5 | < 15 | Calcium, phosphorus | Every 1 to 3 months |

| PTH | Every 3 to 6 months | ||

| Alkaline phosphatase | Every 12 months |

| Medication | Comments |

|---|---|

| Calcimimetics* | |

| Cinacalcet (Sensipar) Etelcalcetide (Parsabiv) Evocalcet (not available in the United States) | Decrease PTH Adverse effects: hypocalcemia, nausea May reduce need for parathyroidectomy in adults undergoing dialysis No effect on cardiovascular events, fractures, mortality |

| Calcium supplements | |

| Calcium carbonate Calcium citrate Calcium gluconate | Increase serum calcium |

| Phosphate binders | |

| Calcium based Calcium acetate (21% elemental calcium) Calcium carbonate (40% elemental calcium) Non–calcium based Lanthanum (Fosrenol) Sevelamer | Decrease serum phosphorus, PTH Adverse effects: hypercalcemia (calcium-based medications), kidney stones (calcium-based medications), gastrointestinal upset (lanthanum, sevelamer), constipation (sevelamer), metabolic acidosis (sevelamer hydrochloride) No effect on cardiovascular events, stroke, fracture, mortality Higher cost (non–calcium-based medications) |

| Vitamin D analogues | |

| Calcifediol (25-hydroxycholecalciferol) Calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxy-cholecalciferol; Rocaltrol) Doxercalciferol (1alpha-hydroxyergocalciferol; Hectorol) Paricalcitol (1alpha-hydroxyergocalciferol; Zemplar) | Increase serum calcium and phosphorus Decrease PTH and bone resorption Not shown to cause hypercalcemia |

| Vitamin D supplements | |

| Cholecalciferol (D3) Ergocalciferol (D2) | Increase 25-hydroxyvitamin D and serum calcium |

Limited evidence shows that dietary interventions to increase calcium intake and reduce phosphorus and protein intake can improve CKDBMD.9 The Endocrine Society recommends supplementation with 50,000 IU of vitamin D2 or D3 once per week for eight weeks or its equivalent of 6,000 IU per day of vitamin D2 or D3 to achieve a 25-hydroxyvitamin D level above 30 ng per mL, followed by maintenance therapy of 1,500 to 2,000 IU per day.10 Phosphate levels can be reduced through dietary restriction and phosphate binders, which include calcium-based and non–calcium-based agents. However, phosphate binders have not demonstrated clinically relevant effects on bone disease, cardiovascular disease, or mortality in patients with CKD who are not undergoing dialysis.24

After management of calcium, vitamin D, and phosphate levels, calcimimetic agents (which reduce secretion of PTH by binding to the CASR) and vitamin D analogues may be considered for reduction of persistently elevated PTH levels in adults with stage 4 or 5 CKD and severe, progressive hyperparathyroidism.8 However, the optimal PTH level is unknown. Although calcimimetics have been shown to effectively lower PTH levels, they may cause hypocalcemia and have not been shown to reduce fractures, cardiovascular disease, or mortality.25,26

In patients with secondary hyperparathyroidism who are undergoing dialysis, parathyroidectomy improves hypercalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, bone mineral density, and health-related quality of life and is associated with 15% to 57% greater survival.27

Hypoparathyroidism

Hypoparathyroidism is rare and usually caused by iatrogenic destruction of the parathyroid glands during anterior neck surgery (75% of cases).28,29 Other, less common etiologies include autoimmune, genetic, metabolic, and malignant causes. Hypoparathyroidism is due to inadequate PTH secretion or an activating mutation of the CASR gene, either of which results in renal calcium loss, decreased osteoclast activity, and decreased production of 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D.1,29 This typically leads to signs and symptoms consistent with hypocalcemia (Table 11,2,4–6). Figure 3 is an algorithm for evaluating symptomatic or incidental hypocalcemia,7–11 and Table 6 lists common laboratory findings based on etiology.2 Hypoparathyroidism is diagnosed by a low or normal intact PTH level with concomitant low serum corrected calcium level and normal serum magnesium level.1,11,29,30

| Condition | Level | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PTH | Phosphorus | 25-hydroxyvitamin D | |

| Calcium-sensing receptor mutation | Normal or low | Elevated | Normal |

| Chronic kidney disease | Elevated | Elevated | Normal |

| Hypoparathyroidism | Low | Elevated | Normal |

| PTH resistance (pseudohypoparathyroidism) | Elevated | Elevated | Normal |

| Vitamin D deficiency | Elevated | Normal or low | Low |

In chronic hypoparathyroidism, goals of treatment are preventing symptoms of hypocalcemia, maintaining serum calcium concentration at the low end of the normal range while also avoiding hypercalcemia, and limiting hypercalciuria.12,28 Oral calcium (1.5 to 3 g of elemental calcium per day) and vitamin D analogues, such as calcitriol (1,25-dihydroxycholecalciferol; Rocaltrol), are the mainstays of therapy.1,12 In the absence of adequate PTH, these supplements may lead to hypercalciuria and subsequent complications of nephrocalcinosis and nephrolithiasis. Thiazide diuretics can mitigate these effects by decreasing hypercalciuria.12

Other Parathyroid Disorders

MEN is a rare, diverse group of familial disorders characterized by benign and malignant tumor formation of various endocrine glands. MEN1 encompasses a variety of tumors commonly involving the parathyroid gland, pituitary gland, and pancreas.31 MEN2A includes medullary thyroid carcinoma, pheochromocytoma, and hyperparathyroidism.31

Given the autosomal dominant inheritance pattern of MEN syndromes, family physicians may need to discuss screening for family members. Genetic screening and laboratory monitoring are recommended for all first-degree relatives of patients with known MEN1 or MEN2 mutations.31–33 Subtotal parathyroidectomy is typically indicated for all patients with MEN syndromes who are surgical candidates. The approach depends on the location, pathology, and extent of tumor involvement.31,33

Although rare, parathyroid cancer can affect 0.5% to 5% of people with primary hyperparathyroidism and may present with marked hypercalcemia, a palpable cervical mass, or laryngeal nerve palsy.34 Diagnosis of parathyroid cancer is difficult because of the lack of unique biomarkers and imaging characteristics and is often made postoperatively. Treatment involves surgical resection and mitigating hypercalcemia, which can lead to significant morbidity and mortality.34

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Michels and Kelly.2

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms hypocalcemia, hypercalcemia, hyperparathyroidism, and hypoparathyroidism. Also searched were Essential Evidence Plus, the Cochrane database, and reference lists of retrieved articles. Search dates: February to October 2021.