Am Fam Physician. 2022;105(4):377-385

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) recurrence rates are three times higher in patients with chronic or no risk factors compared with those who have transient risk factors after stopping anticoagulation therapy. In patients with unprovoked VTE, age-appropriate screening is sufficient evaluation for occult malignancy. Thrombophilia evaluation should be considered only in selected patients because routine evaluation has not been shown to improve outcomes. Patients with VTE should receive three months of anticoagulation therapy. The context of the initial VTE, risk of bleeding and recurrence, and patient preference should be considered when determining whether to continue treatment beyond the initial three months. There is growing evidence regarding the use of risk assessment models to determine risk of recurrence, but this has not been incorporated into guidelines. All pregnant patients with a prior VTE should receive postpartum prophylaxis for six weeks. Antepartum prophylaxis should be used in pregnant people with a history of unprovoked or hormonally induced VTE. High-risk patients undergoing surgery may require extended VTE prophylaxis postoperatively.

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), which includes pulmonary embolism (PE) and deep venous thrombosis (DVT), occurs in 300,000 to 600,000 people (1 to 2 per 1,000) and accounts for up to 100,000 deaths annually in the United States.1 Literature has traditionally categorized VTE as provoked (i.e., at least one identifiable risk factor) or unprovoked (i.e., no identifiable risk factors), but newer literature distinguishes patients with VTE as having transient (i.e., reversible) or chronic risk factors.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Perform only age-appropriate cancer screening to detect occult malignancy in patients with VTE.10,22,23 | A | NICE guidelines, one randomized controlled trial, one meta-analysis |

| Do not routinely test for thrombophilia in patients with provoked VTE. Routine testing in patients with unprovoked VTE is discouraged.10,26,27 | A | NICE guidelines, one randomized controlled trial, one meta-analysis |

| Patients with VTE due to a transient risk factor (provoked) can stop anticoagulation after three months of treatment.30 | C | CHEST guidelines |

| Patients with VTE due to chronic risk factors or with no identifiable risk factors (unprovoked) should continue anticoagulation indefinitely unless they are at high risk of bleeding.10,30 | C | NICE and CHEST guidelines |

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not test for protein C, protein S, or antithrombin III levels during an active clotting event to diagnose a hereditary deficiency. These tests are not analytically accurate during an active clotting event. | American Society for Clinical Pathology |

| Do not do workup for clotting disorder (order hypercoagulable testing) for patients who develop a first episode of deep venous thrombosis from a known cause. | Society for Vascular Medicine |

| Do not test for thrombophilia in adult patients with venous thromboembolism caused by major transient risk factors (e.g., surgery, trauma, prolonged immobility). | American Society of Hematology |

Patients with a provoked VTE due to a transient risk factor have only a 3.3% risk of recurrence in the first year after stopping anticoagulation, whereas patients with an unprovoked VTE have a 10.3% risk of recurrence. The recurrence risk for patients with provoked VTE does not increase significantly after the first year, but the risk for patients with unprovoked VTE increases more than 30% after 10 years.2–5 The mortality rate for unprovoked recurrent VTE is 3.8% (95% CI, 2.0% to 6.1%), ranging from 5% to 13%.4,6,7 This article aims to help physicians assess risks and benefits of prolonged anticoagulation therapy and address considerations in specific populations to reduce the risk of recurrent VTE.

Risk Factors

Performing a thorough medical history and confirming the context of the initial VTE are foundational to identifying risk factors for VTE recurrence. An important unmodifiable risk factor is biologic sex. Several studies have shown a higher risk of recurrence in men with provoked VTE (1.4-fold increase) and unprovoked VTE (1.8-fold increase).4,8,9 Risk factors for VTE are listed in Table 1.10–14

| Chronic or potentially persistent risk factors Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome Autoimmune disease (e.g., collagen vascular disease, rheumatoid arthritis) Body weight < 110 lb (50 kg) or > 264 lb, 9 oz (120 kg); body mass index > 30 kg per m2 Chronic immobilization Chronic infections Heart failure Inflammatory bowel disease Male sex Malignancy Medication use (especially hormone therapy, combined oral contraceptives, testosterone, and heparin) Myeloproliferative disorders Nephrotic syndrome Recurrent pregnancy loss Major transient risk factors Hospitalization > three days with limited mobility Hospitalization for COVID-19 treatment Immobilization (leg injury limiting mobility or bed rest for ≥ three days) Surgery (general anesthesia lasting > 30 minutes) Trauma Minor transient risk factors Hospitalization < three days Oral contraceptives or hormone therapy Pregnancy Presence of a major risk factor one to three months before initial venous thromboembolism Prolonged travel (≥ two hours; highest risk with air travel > four hours or car travel > eight hours in a 24-hour period) Surgery (general anesthesia < 30 minutes) |

The location of the VTE is important because a proximal DVT has up to 4.8 times the risk of recurrence as a distal DVT (e.g., below the knee).4,15–17 In one study, patients with VTE of an iliac vein had twice the risk of recurrence as those with VTE in femoral or distal locations.15 In a meta-analysis of patients with an initial VTE, patients with a distal DVT had only a 1.9% risk of recurrence in the first year after stopping anticoagulation.4 The risk of VTE recurrence is higher in patients who have a central PE compared with a noncentral PE.18

Elevated d-dimer levels posttreatment in unprovoked VTE predict an increased recurrence risk (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.27).16 A study evaluating patients with unprovoked VTE found that those with low d-dimer levels (less than 250 μg per L) three weeks after completing anticoagulation therapy had a 3.7% probability of recurrence in two years, whereas those with high levels (250 μg per L or more) had an 11.5% probability of recurrence.19

Evaluation for Malignancy

Up to 20% of VTEs occur in patients with cancer,20,21 and malignancy is associated with higher rates of recurrence. Specific cancers with higher recurrence rates include brain, myeloproliferative, ovarian, lung, and gastrointestinal (noncolorectal) cancers, as well as any advanced cancer. Stage IV pancreatic cancer has the highest association with recurrence, with an HR of 6.38.5

Guidelines do not recommend additional testing for occult malignancy beyond age-appropriate screening. Additional testing has not been shown to improve outcomes and is not cost-effective.10,22,23 Blood tests (e.g., complete blood cell count, complete metabolic panel, prothrombin time), physical examination, and history are sufficient to identify abnormalities that may prompt further evaluation for malignancy. An abnormal location of thrombosis (e.g., splanchnic or cerebral vein), family history of cancer, recurrence while on anticoagulation, or additional symptoms (e.g., weight loss) may warrant further evaluation or hematology referral.24,25 Splanchnic or cerebral vein thrombosis should prompt evaluation for myeloproliferative disorder.25

Evaluation for Thrombophilia

Guidelines recommend against testing for thrombophilia in patients with provoked VTE and discourage routine testing in those with unprovoked VTE.10,26–28 The presence of one thrombophilic condition confers a 1.4-fold increased risk of recurrent VTE, and the risk is higher with homozygous factor V Leiden mutations (odds ratio [OR] = 2.7) and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (40% increased risk).26–28 Routine testing for thrombophilia has not been shown to improve patient outcomes.27,28

Testing for thrombophilia could be considered in certain situations but only if results would influence the treatment plan (e.g., antiphospholipid antibody syndrome for which warfarin is the preferred treatment over direct oral anticoagulants [DOACs]).29 Patients who had an initial VTE before 50 years of age, have had recurrent pregnancy loss, have a first-degree family member who had an initial VTE before 50 years of age, have recurrent VTE, have arterial and venous thrombosis, or have VTE in an unusual site may consider thrombophilic testing if they are interested in discontinuing anticoagulation because of bleeding risk, intolerance, cost, or other factors.10,28

Physicians should avoid testing during the acute event when inflammation and anticoagulation could cause false results and should wait until treatment is complete (two weeks after stopping warfarin, two to three days after stopping DOACs) or after two to three months of continuous therapy.28 Results of testing performed during anticoagulation therapy should be interpreted in consultation with a hematologist.28 If indicated, testing for antiphospholipid antibodies against cardiolipin and beta-2 glycoprotein 1 and testing for inherited thrombophilias (factor V Leiden gene mutation, prothrombin gene mutation, and functional assays for antithrombin and proteins C and S) are suggested.28

Risk Assessment Models for Predicting Recurrence

Guidelines do not recommend the use of any risk assessment model to determine the need for continued anticoagulation therapy for secondary prevention.10,30,31 The American Society for Hematology recommends against the use of risk assessment models because most patients with unprovoked VTE should continue anticoagulation therapy indefinitely.31 The American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST) guidelines note that d-dimer level and patient sex may influence the decision to continue anticoagulation, without endorsing any specific risk assessment model.30

If patients desire more individualized risk information, several risk assessment models can provide additional data. The HERDOO2 model (https://www.mdcalc.com/herdoo2-rule-discontinuing-anticoagulation-unprovoked-vte) assesses the risk of unprovoked VTE recurrence in women using d-dimer level (250 μg per L or more), body mass index (30 kg per m2 or higher), age (65 years and older), and any signs of postthrombotic syndrome (i.e., edema, erythema, or hyperpigmentation). A score of 0 or 1 is correlated with a 3% risk of recurrence per patient-year.7,32 In one study, the HERDOO2 model identified more than one-half of the participants as having low risk of recurrence.32

The HERDOO2 model is the only prospectively validated tool, but the Vienna model, Leiden Thrombosis Recurrence Risk Prediction model, and DASH (d-dimer, age, sex, and hormone use) model are being studied.33 The modified Ottawa score assesses six-month recurrence risk for cancer-associated thrombosis.34 These models require continued study in the DOAC era and with a more diverse patient population (92% of participants self-identified as White in one study 7) before they can be incorporated into guidelines.35

Evaluation of Bleeding Risk

The annual risk of major bleeding while undergoing anticoagulation is 1.2% (12% over 10 years), but the risk is less with DOACs compared with warfarin (1.1 vs. 1.7 events per 100 person-years, respectively).4,36 Although the overall risk of death from major bleeding while undergoing anticoagulation has been shown to be 1.3% over 10 years (a 2.6-fold increase compared with the general population), the risk of death from PE after stopping anticoagulation therapy is similar at 1.5% over the same period.4,30 However, a recent meta-analysis and systematic review showed a case fatality rate of major bleeding that is two to three times higher than that of recurrent VTE, especially in patients who are older than 65 years, use antiplatelet therapy, or who have a creatinine clearance less than 50 mL per minute per 1.73 m2 (0.83 mL per second per m2) or with a hemoglobin level lower than 10 g per dL (100 g per L).36

No risk assessment models have been prospectively validated to assess bleeding risk in VTE. The CHEST scoring system (Table 237,38) has been recommended in guidelines,30 but recent evidence has questioned its validity.39 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines were recently updated to recommend using the ORBIT model (sex, age older than 74 years, history of major bleeding, glomerular filtration rate less than 60 mL per minute per 1.73 m2, antiplatelet use, baseline hemoglobin level40) for patients with atrial fibrillation over the previously recommended HAS-BLED model (hypertension, abnormal renal and liver function, stroke, bleeding, labile international normalized ratio, elderly [older than 65 years], drugs and alcohol; https://www.mdcalc.com/has-bled-score-major-bleeding-risk). However, the ORBIT model does not have evidence supporting its use in patients with VTE, whereas the HAS-BLED model does have some evidence of utility in these patients.10,41 Any risk assessment model can help identify modifiable risk factors and should be used if bleeding complications occur to weigh the risks and benefits of continued anticoagulation therapy.42

| Risk Factors | |||

| Age > 65 years | Diabetes mellitus | Previous stroke | |

| Age > 75 years* | Frequent falls | Recent surgery | |

| Alcohol abuse | Liver failure | Renal failure | |

| Anemia | Metastatic cancer | Thrombocytopenia | |

| Antiplatelet therapy | Poor anticoagulant adherence | ||

| Cancer | Previous bleeding problems | ||

| Comorbidity and reduced functional capacity | Diabetes mellitus | ||

| Estimated absolute risk (%) | |||

| Categorization of risk | Low risk (no risk factors) | Moderate risk (1 risk factor) | High risk (≥ 2 risk factors) |

| Initial risk (0 to 3 months) | 1.6 | 3.2 | 12.8 |

| Risk beyond 3 months | 0.8 | 1.6 | ≥ 6.5 |

Treatment and Prevention

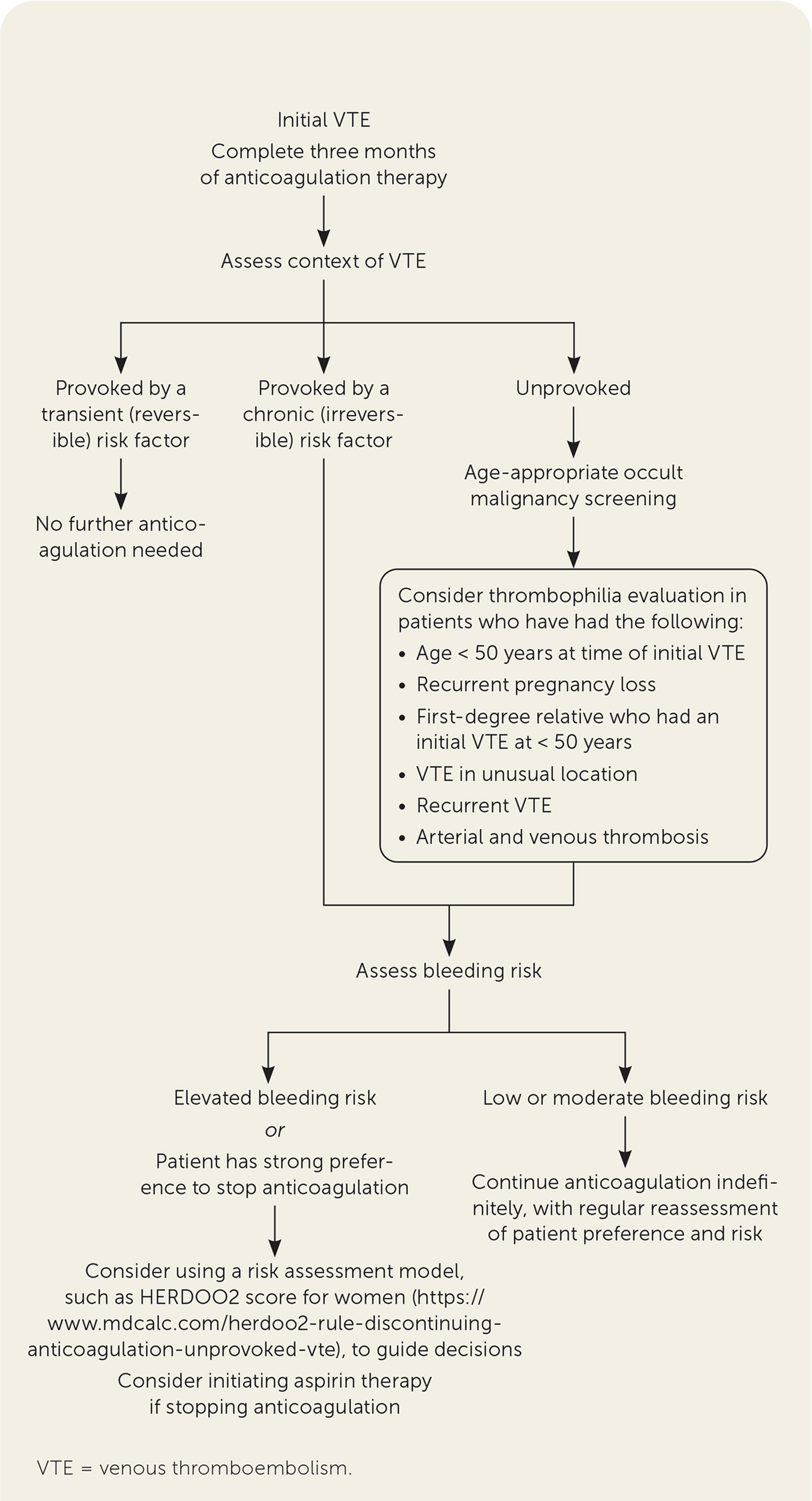

Management of VTE, including anticoagulation selection, was addressed in a previous American Family Physician article.43 Initial episodes of VTE should be treated with three months of anticoagulation.43 Guidelines and shared decision-making based on bleeding risk, tolerability, clinical context, and patient preference should determine whether anticoagulation is continued after three months10,30,31 (Figure 110,22,27,30–32,44).

According to the 2016 CHEST guidelines, no further anticoagulation therapy after the initial three months of treatment is recommended for patients with VTE provoked by transient risk factors (Table 3).30,37 For patients with VTE that is unprovoked or provoked by a chronic risk factor, the decision to continue treatment for secondary prevention should be primarily influenced by bleeding risk. Patients with low to moderate bleeding risk should continue anticoagulation indefinitely.10,30 A recent update to the 2016 CHEST guidelines added a weak recommendation for reducing the anticoagulation dosage after the initial three months (apixaban [Eliquis], 2.5 mg twice daily, or rivaroxaban [Xarelto], 10 mg once daily).45 Patients with elevated bleeding risk should discontinue therapy at three months, even after a second unprovoked VTE.30,31 If anticoagulation therapy is discontinued after three months, aspirin therapy should be initiated unless there is a contraindication (number needed to treat [NNT] = 33 per year to prevent one event).10,30,43–45

| Context | Bleeding risk (strength of recommendation) | Risk of recurrent VTE within first year if therapy is discontinued (additional annual risk thereafter); % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low or intermediate | High | ||

| First VTE provoked by surgery | Discontinue (strong) | Discontinue (strong) | 1 (0.5) |

| First VTE provoked by a non-surgical factor | Discontinue (strong) | Discontinue (strong) | 5 (2.5) |

| First unprovoked VTE | Continue (weak) | Discontinue (strong) | 10 (5) |

| Second unprovoked VTE | Continue (strong if low bleeding risk, weak if intermediate bleeding risk) | Discontinue (weak) | 15 (7.5) |

| Cancer-associated VTE | Continue (strong if low bleeding risk, weak if intermediate bleeding risk) | Continue (weak) | Varies |

| Distal deep venous thrombosis | Discontinue (strong) | Discontinue (strong) | Unlikely to progress to clinical significance |

Indefinite secondary prevention with DOACs in patients with unprovoked VTE is supported by evidence demonstrating a VTE-related and an overall mortality benefit.46 Warfarin and DOACs have been shown to reduce VTE recurrence (risk ratio [RR] = 0.21 and 0.22, respectively) but increase major bleeding (RR = 2.7 and 1.6, respectively).46 The net mortality benefit, incorporating both the risk of recurrent VTE and the risk of major bleeding, favors warfarin (RR = 0.46; 95% CI, 0.30 to 0.72; NNT = 16) and DOACs (RR = 0.25; 95% CI, 0.16 to 0.39; NNT = 15), but additional data are needed to determine the long-term mortality risk from major bleeding beyond one year of extended anticoagulation therapy.36,46

Inferior vena cava filters provide no benefit for VTE treatment or prevention in patients on anticoagulation therapy.30,47 When inferior vena cava filters are used in patients with contraindications to anticoagulation, they should be removed as soon as the contraindication resolves. Compression stockings are not helpful for prevention of VTE or postthrombotic syndrome, but they may reduce pain or swelling.31,48 Mitigating risk factors (e.g., stopping hormone therapy) can help prevent future VTE.

Special Populations

RECURRENT VTE DURING ANTICOAGULATION THERAPY

Recurrent VTE in patients on full anticoagulation therapy should prompt an assessment of adherence, drug interactions, correct dosing, and patient tolerability of therapy, with close attention to medication administration (e.g., 15- and 20-mg doses of rivaroxaban should be taken with food). DOACs can interact with other medications metabolized by cytochrome P450 3A4 and P-glycoprotein.49 Further evaluation for malignancy or anatomic abnormalities contributing to recurrence should be considered. Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia should be considered in patients taking heparin, and antiphospholipid antibody syndrome should be considered in patients taking a DOAC.

If VTE recurs in a patient taking warfarin or a DOAC, therapy should be switched to low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH). For patients already taking LMWH at the time of recurrence, the dose of LMWH can be increased by one-fourth to one-third.10,30,31 Hematology referral should be obtained when changing to or increasing the dose of LMWH.

PREGNANCY

Pregnancy-related VTE occurs in 1.7 per 1,000 deliveries, with a mortality rate of 1.1 to 1.2 per 100,000 deliveries.50,51 One-half of VTEs associated with pregnancy occur in the postpartum period.50 Patients who develop VTE during pregnancy should be treated until at least six weeks postpartum, ensuring that three months of anticoagulation is completed.52 Newer guidelines strongly recommend LMWH over unfractionated heparin for treatment of VTE in pregnancy.53

Incidence of recurrent VTE is higher in patients with unprovoked VTE (10.4%) compared with pregnancy-induced VTE (5.8%; P = .02), suggesting that pregnancy is a transient risk factor for VTE. However, the risk of a recurrent VTE during pregnancy is higher in patients whose prior VTE was pregnancy-induced (4.5%) vs. unprovoked (2.7%).54 Antepartum VTE prophylaxis is strongly recommended in patients with a history of unprovoked or hormonally associated VTE. All pregnant patients with a history of VTE should receive postpartum prophylaxis for six weeks. Further guidance on antepartum and postpartum prophylaxis for thrombophilias and women undergoing assistive reproductive technologies is included in Table 4.53 Although the risk of VTE extends to 12 weeks postpartum, prophylaxis beyond six weeks is unlikely to be beneficial in most patients, and further studies are needed.53

| Factor | Antepartum prophylaxis | Postpartum prophylaxis |

|---|---|---|

| History of VTE that was unprovoked or associated with a hormonal risk factor | Yes* | Yes* |

| History of VTE provoked by a nonhormonal, temporary risk factor | No | Yes* |

| Heterozygous for factor V Leiden mutation with or without a family history of VTE | No | No |

| Homozygous for factor V Leiden mutation with or without a family history of VTE | Yes | Yes |

| Heterozygous for prothrombin gene mutation with or without a family history of VTE | No | No |

| Homozygous for prothrombin gene mutation without a family history of VTE | No | Yes |

| Homozygous for prothrombin gene mutation with a family history of VTE | No evidence-based antepartum recommendation, but panel members generally favor prophylaxis | Yes |

| Compound heterozygosity with or without a family history of VTE | Yes | Yes |

| Protein C or S deficiency without a family history of VTE | No | No |

| Protein C or S deficiency with a family history of VTE | No | Yes |

| Antithrombin deficiency without a family history of VTE | No | No |

| Antithrombin deficiency with a family history of VTE | Yes | Yes* |

| Combined thrombophilias with or without a family history of VTE | Yes | Yes |

| Women undergoing assisted reproductive therapy | No | Not applicable |

| Women undergoing assisted reproductive therapy who develop severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome | Yes | Not applicable |

| Pregnant patients who require prophylaxis | Use a standard dose of low-molecular-weight heparin prophylaxis | Use either a standard or intermediate dose of low-molecular-weight heparin prophylaxis |

POSTOPERATIVE PERIOD

Surgery is a significant risk factor for VTE, and the risk extends up to three months postoperatively.55 Guidelines recommend a longer duration of VTE prophylaxis after orthopedic, abdominal, and pelvic surgeries.56 Patients undergoing total hip or knee replacements should complete 10 to 14 days of postoperative prophylaxis, with consideration of up to 35 days after hip replacements.57 Patients with cancer who are undergoing major surgery should receive postoperative prophylaxis for at least seven to 10 days. Patients undergoing abdominal or pelvic surgery should receive postoperative prophylaxis with LMWH for up to four weeks, especially if they have a history of VTE or other VTE risk factors.5,58 Growing evidence for VTE prophylaxis in high-risk, nonsurgical patients after hospitalization has not yet been incorporated into guidelines.59,60

TRANSGENDER PATIENTS

Thrombophilia testing is not recommended in male-to-female transgender people initiating gender-affirming hormone therapy unless they have a personal or family history of VTE.61 In a study of transgender patients undergoing hormone therapy, those using synthetic estrogens had a 20-fold increased risk of VTE; however, the incidence of VTE decreases with cessation of therapy, and the overall VTE incidence is low in these patients.13,61–63 Use of a DOAC may be considered after shared decision-making for transgender patients with prior VTE or thrombophilia who are taking estrogen therapy for transition.64

COVID-19

COVID-19 is a risk factor for VTE in patients requiring hospitalization but does not appear to increase VTE risk in the outpatient setting.11,12 Studies performed before the Omicron variant showed that VTE occurs in 3% to 21% of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 (8% to 31% of those needing intensive care), and the development of VTE in these patients is associated with twice the overall mortality.11,65–67 For critically ill patients hospitalized with COVID-19, guidelines recommend prophylactic dosing of anticoagulation over therapeutic dosing.68,69 However, therapeutic anticoagulation is recommended for hospitalized patients not in the intensive care unit and who meet the following criteria: low-flow supplemental oxygen is required; d-dimer levels are above the upper limit of normal; and the patient is not at an increased risk of bleeding (i.e., platelet count less than 50 × 103 per μL [50 × 109 per L], hemoglobin less than 8 g per dL [80 g per L], need for dual antiplatelet therapy, bleeding in the past 30 days requiring an emergency department visit or hospitalization, known history of a bleeding disorder, or an inherited or active acquired bleeding disorder).68,69 Treatment with LMWH is preferred over heparin and should continue for 14 days or until hospital discharge. Guidelines do not recommend extended VTE prophylaxis beyond what would normally be considered in hospitalized patients, although it may be reasonable to consider continuing VTE prophylaxis after discharge if high-risk features are present, such as decreased mobility or profound weakness.68

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Galioto, et al.14

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed using the key words deep venous thrombosis, deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis, idiopathic deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, pulmonary embolism prophylaxis, risk of thromboembolism, thromboembolism, or venous thromboembolism. The American College of Chest Physicians, American Society of Hematology, and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence websites were reviewed. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention sources were reviewed for epidemiology data. An Essential Evidence Plus summary was reviewed that included clinical rules, POEMs, and Cochrane reviews. Search dates: January 2021, April 2021, November 2021, and January 2022.