Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(3):288-298

Patient information: See related handout on thrombocytopenia, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Thrombocytopenia is a platelet count of less than 150 × 103 per μL and can occur from decreased platelet production, increased destruction, splenic sequestration, or dilution or clumping. Patients with a platelet count greater than 50 × 103 per μL are generally asymptomatic. Patients with platelet counts between 20 and 50 × 103 per μL may have mild skin manifestations such as petechiae, purpura, or ecchymosis. Patients with platelet counts of less than 10 × 103 per μL have a high risk of serious bleeding. Although thrombocytopenia is classically associated with bleeding, there are conditions in which bleeding and thrombosis can occur, such as antiphospholipid syndrome, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and thrombotic microangiopathies. Patients with isolated thrombocytopenia in the absence of systemic illness most likely have immune thrombocytopenia or drug-induced thrombocytopenia. In stable patients being evaluated as outpatients, the first step is to exclude pseudothrombocytopenia by collecting blood in a tube containing heparin or sodium citrate and repeating the platelet count. If thrombocytopenia is confirmed, the next step is to distinguish acute from chronic thrombocytopenia by obtaining or reviewing previous platelet counts. Patients with acute thrombocytopenia may require hospitalization. Common causes that require emergency hospitalization are heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, thrombotic microangiopathies, and the hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count (HELLP) syndrome. Common nonemergency causes of thrombocytopenia include drug-induced thrombocytopenia, immune thrombocytopenia, and hepatic disease. Transfusion of platelets is recommended when patients have active hemorrhage or when platelet counts are less than 10 × 103 per μL, in addition to treatment (when possible) of underlying causative conditions. It is important to ensure adequate platelet counts to decrease bleeding risk before invasive procedures; this may also require a platelet transfusion. Patients with platelet counts of less than 50 × 103 per μL should adhere to activity restrictions to avoid trauma-associated bleeding.

Normal platelet counts range from 150 to 450 × 103 per μL; however, some laboratories may specify a slightly different range. Males, older adults, and White populations tend to have lower platelet counts.1,2 Modifying normal platelet count ranges based on age, sex, and ethnicity has been proposed, but no consensus has been established.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Initial treatment for immune thrombocytopenia is corticosteroid therapy or intravenous immune globulin (human) infusion. Recurrent or unresponsive cases are treated with thrombopoietinreceptor agonists or immunomodulators (e.g., rituximab).25,26 | A | Consistent findings from randomized controlled trials |

| Treatment of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia is discontinuation of heparin and immediate anticoagulation with a nonheparin anticoagulant to prevent thromboembolic complications.31–33 | C | Evidence-based practice guidelines |

| Patients should have a minimum platelet count of 40 to 50 × 103 per μL for most major invasive procedures and surgeries.49,50 | C | Evidence-based practice guidelines |

| Prophylactic platelet transfusions are recommended for patients with platelet counts less than 10 × 103 per μL or at higher counts with signs of bleeding.49–53 | C | Evidence-based practice guidelines |

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| Do not test or treat for suspected heparin-induced thrombocytopenia in patients with a low pretest probability of heparin-induced thrombocytopenia. | American Society of Hematology |

| Do not treat patients with immune thrombocytopenic purpura in the absence of bleeding or a very low platelet count. | American Society of Hematology |

This review defines mild thrombocytopenia as a platelet count from 100 to 150 × 103 per μL, moderate as 50 to 99 × 103 per μL, and severe when platelet counts are less than 50 × 103 per μL.

Causes

| Decreased platelet production or function Alcohol use disorder* Bone marrow failure, suppression, or infiltration Congenital platelet disorders† Drug-induced·nonimmune thrombocytopenia Hepatic disease* Infections‡ Myelodysplastic syndrome Nutritional deficiencies (vitamin B12 and folate) Sepsis* | Increased peripheral consumption Alloimmune destruction Disseminated intravascular coagulation* Drug-induced immune thrombocytopenia Heparin-induced thrombocytopenia Immune thrombocytopenia Infections‡ Mechanical destruction Paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria Preeclampsia/HELLP syndrome Thrombotic microangiopathy (thrombocytopenic purpura, hemolytic uremic syndrome, drug-induced thrombotic microangiopathy) Vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia | Sequestration/other Alcohol use disorder* Dilutional thrombocytopenia Gestational thrombocytopenia Hepatic disease* Hypersplenism Pseudothrombocytopenia |

Although thrombocytopenia is classically associated with bleeding, there are also conditions in which bleeding and thrombosis can occur. These include antiphospholipid syndrome, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), thrombotic microangiopathies (i.e., thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and hemolytic uremic syndrome), and disseminated intravascular coagulation.6 The pathogenesis of these conditions relates to mechanisms such as the development of immune complexes promoting excessive thrombin production, endothelial wall injury with platelet microthrombi formation, or disproportionate consumption of coagulation factors.

Bleeding Risk

The risk of bleeding at different levels of thrombocytopenia is not linear; therefore, there is no consensus on a safe level at which bleeding will not occur. Additional variables such as coagulation disorders, medications, and systemic diseases further affect bleeding risk. Patients with platelet counts greater than 50 × 103 per μL are generally asymptomatic. Patients with counts from 20 to 50 × 103 per μL often experience easy bruising, petechiae, and prolonged bleeding associated with minimal trauma. A high risk of spontaneous bleeding usually occurs when platelet counts are less than 10 × 103 per μL, and thrombocytopenia at that level should be considered a hematologic emergency.7,8

The finding of isolated mild thrombocytopenia has a favorable prognosis. A prospective study followed 217 individuals with platelet counts ranging from 100 to 150 × 103 per μL over 10 years. In 64% of patients, platelet counts normalized or stayed mildly thrombocytopenic without sequelae. The probability of developing immune thrombocytopenia (ITP) or an additional autoimmune disorder was approximately 7% and 12%, respectively. Only 2% of the study participants developed myelodysplastic syndrome, all of whom were older adults.9

Inpatient Evaluation

The urgency for evaluating thrombocytopenia is dependent on severity and associated symptoms. Thrombocytopenia requires hospitalization and immediate evaluation if any of the following red flag findings are present: major bleeding, platelet count less than 10 × 103 per μL, evidence of hemolysis on peripheral smear, new neurologic or renal dysfunction, recent exposure to heparin products, associated coagulation abnormalities, or vascular findings (e.g., extremity pain, swelling, skin necrosis). Patients with concomitant life-threatening hemorrhage (e.g., intracranial, gastrointestinal, genitourinary), anemia, leukopenia, leukocytosis, or other associated severe illnesses (e.g., sepsis) also warrant urgent hospitalization.

Outpatient Evaluation

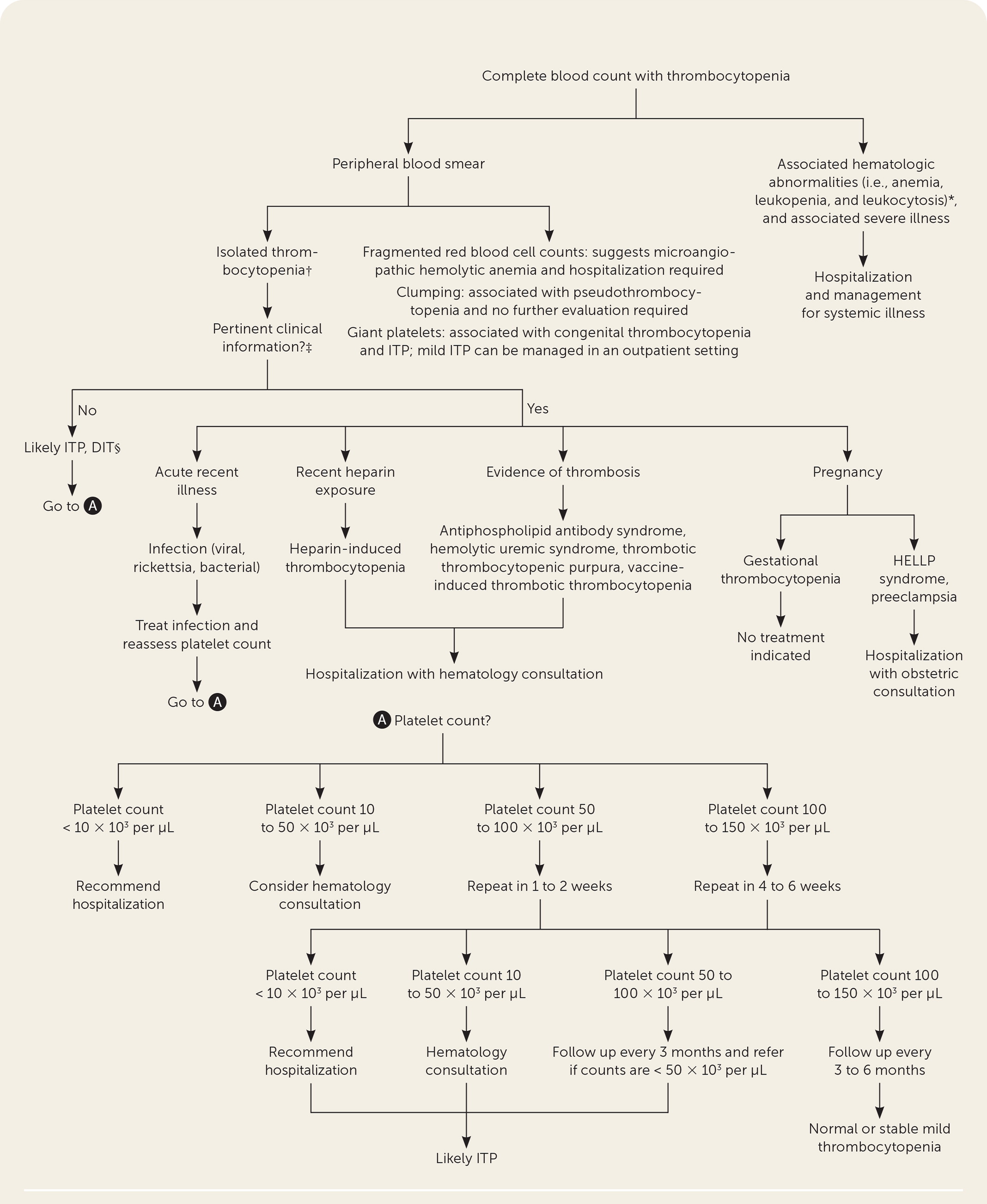

Without situations requiring hospitalization, thrombocytopenia is often an incidental finding on blood counts obtained in routine practice, and the cause is not immediately apparent. The challenge is distinguishing patients with pseudothrombocytopenia, acute vs. chronic thrombocytopenia, and those with platelet counts within the normal range who had a precipitous drop in platelet count (e.g., a decrease from 350 to 160 × 103 per μL). Figure 1 is an algorithm for the evaluation of thrombocytopenia.

EXCLUDING PSEUDOTHROMBOCYTOPENIA

Pseudothrombocytopenia occurs when the clumping of platelets in the collection tube leads to a false low platelet count. Clinicians should first determine if the low platelet count is accurate by repeating the test and recollecting the blood in a tube containing heparin or sodium citrate to avoid platelet aggregation, and requesting a manual platelet count to confirm if thrombocytopenia is present.10

DISTINGUISHING ACUTE VS. CHRONIC THROMBOCYTOPENIA

Previous platelet counts help make the distinction between acute and chronic thrombocytopenia. If previous platelet counts cannot be obtained for comparison, thrombocytopenia should be considered acute until proven otherwise. Verified chronic thrombocytopenia is unlikely to be a condition requiring emergency intervention.

HISTORY

For verified thrombocytopenia, clinicians should ask about a history of prolonged or excessive bleeding, family history of bleeding disorders, recent illnesses, recent hospitalization with heparin exposure, and medical or surgical history (i.e., autoimmune disorders, immunodeficiency syndromes, hepatic disease, hematologic disorder, malignancy history, organ transplantation, bariatric surgery, and valvular heart surgery). The presence of any of these conditions can indicate the cause of thrombocytopenia. It is also important to obtain a detailed history of medication use. Common medications implicated as a cause of thrombocytopenia are listed in Table 2. Alcohol consumption history should not be overlooked because 3% to 43% of alcohol-dependent individuals develop thrombocytopenia.11

| Antibiotics: beta-lactams, cephalosporins, linezolid (Zyvox), penicillins, rifampin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, vancomycin |

| Anticoagulants: heparins |

| Antiepileptic agents: carbamazepine (Tegretol), lamotrigine (Lamictal), levetiracetam (Keppra), phenytoin (Dilantin), valproic acid (Depakene) |

| Antihypertensive agents: captopril, chlorthalidone, hydrochlorothiazide, methyldopa, spironolactone |

| Antineoplastic agents: bleomycin, fludarabine, interferon alfa, oxaliplatin (Eloxatin), rituximab, trastuzumab (Herceptin) |

| Benzodiazepines: diazepam (Valium), lorazepam (Ativan) |

| Cardiac agents: amiodarone, digoxin, furosemide (Lasix) |

| Chemotherapeutic agents |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors: tirofiban (Aggrastat), eptifibatide |

| Histamine H2 antagonists: cimetidine (Tagamet) |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: acetaminophen, diclofenac, gold compounds (Ridaura), ibuprofen, indomethacin, naproxen, piroxicam (Feldene) |

| Over-the-counter* definite association: cranberry juice, Jui herbal tea, Lupinus termis bean, cow's milk, tahini (sesame seed paste) |

| Over-the-counter* possible association: chromium picolinate, Echinacea pallida, Hypericum perforatum (St. John Wort), nicotinamide, vitamin A palmitate, Cupressus funebris (mourning cypress) |

| Psychotropic agents: chlorpromazine, citalopram (Celexa), haloperidol, olanzapine (Zyprexa), risperidone (Risperdal) |

| Quinine: these chemicals are enantiomers (a mirror image of each other); quinine is a class 1 antiarrhythmic agent and has been used for treatment of malaria |

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The physical examination should assess for petechiae, purpura, ecchymosis, and evidence of mild bleeding (e.g., epistaxis, mucosal). All patients should be evaluated for lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, venous thromboembolism, and vascular necrosis, which may suggest a systemic condition (e.g., thrombotic microangiopathies, lymphoproliferative disorders).12 Additional clinical considerations to aid in the diagnosis of thrombocytopenia are listed in Table 3.13–17

| Clinical consideration | Possible diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Acute timing | Acute infection (primarily viral), acute leukemias, alloimmune destruction, aplastic anemia, chemotherapy or irradiation, drug-induced thrombocytopenia, HELLP syndrome, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, immune thrombocytopenia, lymphomas, malignancies with marrow infiltration, thrombocytopenic purpura, or hemolytic uremic syndrome |

| Chronic timing | Alcohol use disorder, congenital thrombocytopenia, chronic immune thrombocytopenia, hepatic disease, myelodysplastic syndrome |

| History | |

| Acute heavy alcohol ingestion | Alcohol-induced thrombocytopenia |

| Autoimmune disorder | Immune thrombocytopenia, rheumatoid arthritis, SLE |

| Cardiac valve replacement | Mechanical destruction |

| Family history | Congenital thrombocytopenia |

| Hospitalization | Drug-induced thrombocytopenia, disseminated intravascular coagulation, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, sepsis, thrombotic microangiopathies |

| Immunization | Immune thrombocytopenia, vaccine-induced thrombotic thrombocytopenia: COVID-19; measles, mumps, and rubella; varicella; influenza A (H1N1) |

| Medication/supplement change | Medication-induced thrombocytopenia (Table 2), drug-induced thrombotic microangiopathies (Table 5) |

| Pregnancy | Gestational thrombocytopenia, HELLP syndrome/preeclampsia (Table 6) |

| Transfusion/high-risk behavior | Alloimmune destruction, viral infections |

| Travel | Babesiosis, dengue fever, ehrlichiosis, malaria, rickettsia, Zika virus |

| Symptoms | |

| Abdominal pain | Hepatic disease, HELLP syndrome, hemolytic uremic syndrome, hypersplenism |

| Bleeding (e.g., epistaxis, hematuria, mucosal, rectal, vaginal) | Nonspecific, evidence of severe thrombocytopenia of any etiology |

| Fever | Drug-induced thrombotic microangiopathies, viral infections, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, rickettsia |

| Weight loss or night sweats | HIV, malignancies |

| Physical examination | |

| Acute rash (e.g., petechiae, purpura, ecchymosis) | Nonspecific, evidence of severe thrombocytopenia; rickettsia; SLE; viral infections have additional dermatologic lesions |

| Hepatosplenomegaly* | Acute leukemias, autoimmune, hepatic disease, lymphomas, hypersplenism, viral infections |

| Lymphadenopathy | Acute leukemias, lymphomas, SLE, viral infections |

| Neurologic | Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, drug-induced thrombotic micro-angiopathies, vaccine-induced thrombotic thrombocytopenia |

| Thrombosis | Antiphospholipid syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation, drug-induced thrombotic microangiopathies, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, hemolytic uremic syndrome, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, vaccine-induced thrombotic thrombocytopenia |

LABORATORY TESTING

A peripheral blood smear is recommended for all patients with thrombocytopenia to evaluate the presence of fragmented red blood cells (schistocytes), which suggests microangiopathic hemolytic anemia (associated with thrombocytopenia). In the absence of schistocytes, any additional laboratory evaluation should be guided by the likelihood of preexisting medical conditions.

In patients who are asymptomatic, a reasonable approach includes a disseminated intravascular coagulation panel (e.g., fibrinogen, d-dimer, coagulation factors); hemolysis screen (i.e., direct antiglobulin [Coombs] test, haptoglobin, and lactate dehydrogenase); renal and hepatic function tests; selected viral serologies (e.g., hepatitis, HIV); Helicobacter pylori stool antigen testing, fecal occult blood test, vitamin B12, and folate levels. Additional testing for autoimmune syndromes, antiplatelet antibodies, and thyroid function testing should be considered when clinically indicated.18 These tests identify or eliminate most thrombocytopenia etiologies.

FOLLOW-UP LABORATORY TESTING

Individuals with newly diagnosed mild or moderate thrombocytopenia without red flag findings should have their platelet counts repeated at intervals. Testing should occur in one to two weeks for patients with moderate thrombocytopenia and in four to six weeks for those with mild thrombocytopenia. Patients with moderate to severe thrombocytopenia of unknown etiology or decreasing platelet counts should be referred to hematology.

Patients with stable chronic thrombocytopenia associated with specific medical conditions (i.e., chronic renal or hepatic disease, autoimmune disorders, and congenital thrombocytopenia) do not require increased platelet surveillance or immediate hematology consultation without other complications.

Common Nonemergency Causes

Although numerous conditions are associated with thrombocytopenia, this discussion reviews the causes that primary care clinicians are most likely to encounter.

DRUG-INDUCED THROMBOCYTOPENIA

The reported incidence of drug-induced thrombocytopenia (DIT) is 10 cases per 1 million people per year, but the number is presumed to be higher because of underreporting and underdiagnosis.19 The mechanisms by which drugs cause thrombocytopenia include peripheral platelet destruction, bone marrow suppression, and platelet activation.19 The severity of DIT is variable, and platelet counts rarely drop below 20 × 103 per μL. A detailed history of medication exposure (i.e., over-the-counter drugs, herbal remedies, and supplements) and the onset of thrombocytopenia is critical in determining the likelihood of DIT.13–17 A comprehensive list of all case reports of DIT is available at https://ouhsc.edu/platelets/ditp.html,20 and commonly encountered medications are listed in Table 2.

Drug-specific antiplatelet antibody testing can be useful when patients are prescribed multiple medications known to cause DIT. However, results are not immediately available and must be obtained in specialized laboratories.

The implicated medication usually causes thrombocytopenia within three to 10 days of exposure. Treatment is the discontinuation of the causative medication. Most DIT cases resolve within seven to 10 days after removing the causative medication.21 Clinicians should consider an alternate diagnosis if the patient's platelet count does not improve despite discontinuation of the medication.

IMMUNE THROMBOCYTOPENIA

ITP is the premature splenic destruction of antibody-coated platelets with other hematopoietic cell lines remaining normal. ITP is the most common cause of isolated thrombocytopenia.22 The platelet count is typically less than 100 × 103 per μL; however, it can be severe with life-threatening bleeding.

There is no specific laboratory test for ITP, so it is often a diagnosis of exclusion. Primary ITP is distinguished from secondary ITP by the absence of chronic medical conditions or acute infections. In secondary ITP, patients have associated conditions,23,24 the most common of which are listed in Table 4.

| Autoimmune disorders Antiphospholipid syndrome Evans syndrome Inflammatory bowel disease Rheumatoid arthritis Sarcoidosis Systemic lupus erythematosus Drugs Acetaminophen, abciximab (Reopro), carbamazepine (Tegretol), gold compounds (Ridaura), select monoclonal antibodies Immunodeficiency syndromes Common variable immune deficiency HIV | Infections Cytomegalovirus Epstein-Barr virus Helicobacter pylori Hepatitis C virus HIV Varicella zoster virus Zika virus Lymphoproliferative disorders Autoimmune lymphoproliferative syndrome Chronic lymphocytic leukemia Hodgkin lymphoma Vaccinations Measles, mumps, and rubella |

Patients often require hospitalization, but newly diagnosed ITP with platelet counts of 20 × 103 per μL or greater in patients who are asymptomatic or with minimal mucosal bleeding can be managed in the outpatient setting, provided that definitive hematology follow-up is performed within 24 to 72 hours.25

Initial therapy is corticosteroids or intravenous immune globulin (human) infusion. Recurrent or unresponsive cases are treated with thrombopoietin receptor agonists or immunomodulators (e.g., rituximab).25 Splenectomy is reserved for chronic or recurrent cases when the above therapies are ineffective and the patient has had ITP for at least one year.26

HEPATIC DISEASE

Thrombocytopenia is present in 64% to 84% of patients with chronic hepatic disease.27 The primary mechanism for thrombocytopenia is decreased hepatic synthesis of thrombopoietin, which is essential for the production of platelets. Other associated factors such as splenic sequestration from portal hypertension, bone marrow suppression (i.e., alcohol use and viral infections), and medications may worsen thrombocytopenia.28

Treatment options are limited except for eliminating offending agents (i.e., alcohol) or treating secondary causes of hepatic dysfunction. Platelet transfusions are the standard of care to manage severe thrombocytopenia and for preprocedural prophylaxis to achieve a platelet count of at least 50 × 103 per μL.

Certain thrombopoietin receptor agonists (i.e., avatrombopag [Doptelet] and lusutrombopag [Mulpleta]) have been used to raise platelet counts for patients undergoing invasive procedures. However, these medications require five to seven days to increase platelet counts, limiting their use for urgent procedures.29

Common Causes of Thrombocytopenia Requiring Emergency Care

The following conditions are those that primary care clinicians are most likely to encounter and often require emergency care.

HEPARIN-INDUCED THROMBOCYTOPENIA

Patients exposed to unfractionated or low-molecular-weight heparin are at risk of developing life-threatening thrombotic complications caused by antibodies directed at platelet factor-4/heparin complexes. The condition occurs in 0.2% to 5% of patients exposed to heparins.30

HIT is associated with a decrease of more than 50% in the platelet count within five to 10 days of exposure, although in some cases, a delayed onset occurs. Platelet counts generally are not less than 20 × 103 per μL, and spontaneous bleeding is not typical. However, up to one-third of patients with HIT develop thrombosis, skin necrosis, extremity gangrene, or central organ ischemia/infarction.31

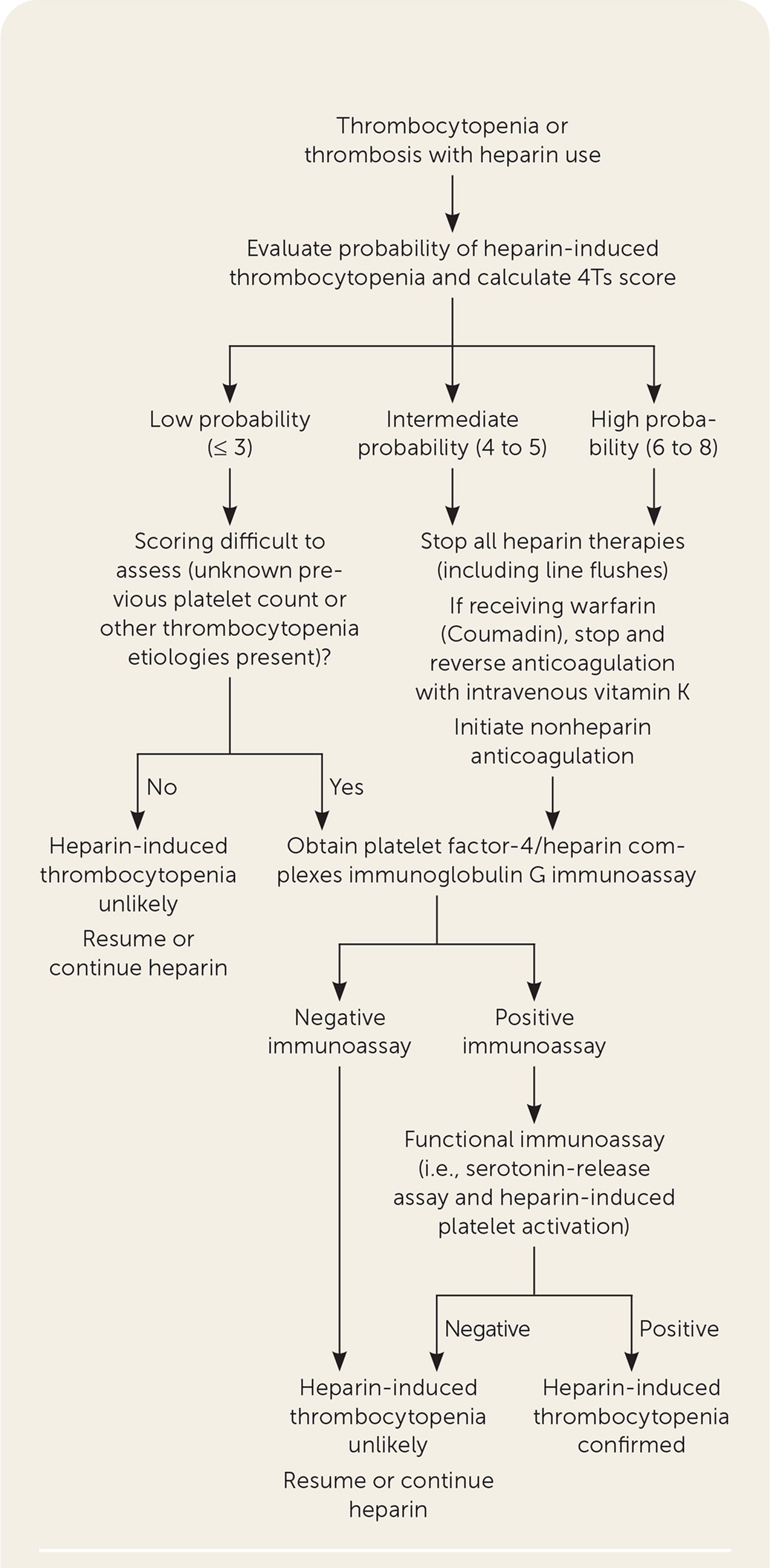

A diagnosis is based on clinical and laboratory evidence (Figure 2).32,33 The 4Ts scoring system (https://www.mdcalc.com/4ts-score-heparin-induced-thrombocytopenia), antiplatelet factor-4/heparin enzyme immunoassay, and functional assay test can increase diagnostic accuracy.34

Treatment is the discontinuation of heparin when HIT is suspected and immediate anticoagulation with a nonheparin anticoagulant to prevent thromboembolic complications.31,32 The preferred initial anticoagulants are parenteral argatroban, bivalirudin (Angiomax), and fondaparinux (Arixtra). The effectiveness of direct oral anticoagulants as initial therapy is less well-established.33 The duration of anticoagulation for isolated HIT is not agreed on and ranges from a minimum of four to six weeks up to three months for all patients with HIT, and three to six months for HIT-related thrombosis.33,35

All patients with HIT should have ultrasonography performed to screen for asymptomatic lower extremity deep venous thrombosis. Patients with an upper extremity central venous catheter require imaging of the limb of the catheter site to detect thrombosis.

THROMBOTIC MICROANGIOPATHIES

Thrombotic microangiopathies are characterized by microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, and thrombosis. These syndromes are uncommon, but require prompt diagnosis because mortality rates are high if unrecognized or untreated. The most common of these disorders are discussed in Table 5.36–43

| Disease | Clinical manifestation | Diagnostic testing | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antiphospholipid syndrome | Variable, recurrent pregnancy loss after 10 weeks' gestation, venous thromboembolism, cerebrovascular accident | Antiphospholipid antibodies (anticardiolipin antibody, lupus anti-coagulant, anti-beta2-glycoprotein) | Aspirin for primary prevention and anticoagulation for secondary prevention |

| Disseminated intravascular coagulation | Severe illness caused by sepsis, malignancy, pregnancy complications (HELLP syndrome), trauma, acute hemolytic transfusion reaction associated with multiorgan dysfunction | Constellation of findings that include abnormal coagulation, decreased fibrinogen, elevated d-dimer, thrombocytopenia, and microangiopathic hemolytic anemia | Supportive; treat underlying etiology |

| Drug-induced thrombotic microangiopathy | Association with certain medications (i.e., quinine, gemcitabine [Gemzar], oxaliplatin [Eloxatin], trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, quetiapine [Seroquel], adalimumab [Humira]), fever, chills, gastrointestinal symptoms, renal dysfunction, and microvascular thrombosis | Microangiopathic anemia, thrombocytopenia, negative direct antiglobulin test, elevated lactate dehydrogenase, renal injury, normal or mildly decreased ADAMTS13 activity, drug-dependent antibodies in immune-mediated cases | Removal of the implicated agent; some cases are indistinguishable from thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, necessitating plasma exchange or anti-complement therapy in unclear cases |

| Hemolytic uremic syndrome (shiga producing Escherichia coli) | More common in children; abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea, renal failure | Shiga toxin testing | Supportive (i.e., dialysis and blood product transfusions) |

| Hemolytic uremic syndrome (atypical) | Neurologic symptoms, gastrointestinal symptoms, respiratory distress, renal dysfunction | Genetic mutations in complement proteins, anticomplement factor H autoantibodies | Plasmapheresis, eculizumab (Soliris; complement inhibitor) |

| Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura | Fever, malaise, neurologic symptoms, seizures, renal dysfunction, microvascular thrombosis | Decreased ADAMTS13 activity | Plasmapheresis or eculizumab in cases of suspected complement-mediated thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura |

| Vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia (AstraZeneca, Johnson & Johnson COVID-19 vaccine) | Symptoms typically 5 to 30 days post-vaccination; symptoms dependent on location of thrombosis (cerebral most common with symptoms of headache, emesis, neurologic findings, and seizures) | History of vaccination, thrombocytopenia; coagulation testing, fibrinogen, d-dimer, platelet factor-4 antibody, imaging of the suspected site of thrombosis | Anticoagulation, neurology and hematology consultation |

Other Considerations

THROMBOCYTOPENIA IN PREGNANCY

Thrombocytopenia develops in 5% to 10% of all pregnancies.44 Unique medical conditions specific to pregnancy must be considered. Table 6 lists the most common causes of thrombocytopenia associated with pregnancy.45–48 Hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count (HELLP) syndrome and preeclampsia are emergent conditions requiring immediate hospitalization.

| Disease (prevalence) | Clinical manifestation | Diagnostic testing | Treatment | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gestational thrombocytopenia (5% to 11%) | Most common cause of thrombocytopenia in pregnancy (80%) Mild thrombocytopenia (> 80 × 103 per μL) Typically develops in second trimester | NA | None indicated | Resolves after pregnancy Infant not affected Can be difficult to distinguish from mild immune thrombocytopenia during pregnancy |

| Preeclampsia (5%)/HELLP syndrome (0.2% to 0.8%) | Onset of hypertension after 20 weeks' gestation (85% present after 34 weeks' gestation) Mild to moderate thrombocytopenia Severe symptoms: altered mental status, visual disturbances, dyspnea, persistent headache, abdominal pain | Proteinuria Thrombocytopenia Hepatic or renal dysfunction in severe cases Hemoconcentration Uric acid elevation Mild lactate dehydrogenase elevation Hemolysis | Magnesium sulfate Timing of delivery Term pregnancy (37 weeks' gestation) to delivery Preterm pregnancy (less than 37 weeks' gestation: expectant management in absence of severe features | Less consensus on management of preterm pregnancies from 34 to 36 weeks and 6 days in absence of severe disease HELLP syndrome complications include hemorrhage, disseminated intravascular coagulation, abruptio placentae, renal failure, pulmonary edema |

| Eclampsia (0.015% to 0.1%) | Similar to preeclampsia with presence of tonic-clonic seizures | Similar to preeclampsia | Magnesium sulfate Intravenous antihypertensive therapy Emergent delivery | Initial management is prevention of hypoxia |

| Acute fatty liver of pregnancy (0.005% to 0.01%) | Third trimester Abdominal pain, malaise, nausea and vomiting, mental status change | Thrombocytopenia Hepatic or renal dysfunction Hypoglycemia Coagulopathy Elevated ammonia Ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging of liver shows fatty infiltration | Prompt delivery when feasible Supportive care | Can be difficult to distinguish from HELLP syndrome; however, blood pressure is typically normal in acute fatty liver of pregnancy Hypoglycemia is not typical for HELLP syndrome |

PLATELET COUNTS BEFORE INVASIVE PROCEDURES

Recommended minimum platelet counts for patients undergoing surgical or invasive procedures are variable and based on limited scientific evidence. The American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline recommends a minimum platelet count of 40 to 50 × 103 per μL, and the AABB (formerly known as the American Association of Blood Banks) recommends greater than 50 × 103 per μL for most major invasive procedures and surgeries.49,50

Procedures such as bone marrow aspiration, central venous catheter insertion or removal, and bronchoscopies (bronchial lavage without biopsy) may be performed with platelet counts of 20 × 103 per μL or greater.49 Patients undergoing neurosurgical and ophthalmologic procedures should have a minimum platelet count of 100 × 103 per μL.51 Patients receiving preprocedure platelet transfusions should have a posttransfusion platelet count to verify an adequate response.

PLATELET TRANSFUSION

In addition to patients undergoing procedures, platelet transfusions are often used in patients with severe thrombocytopenia to treat or prevent acute hemorrhage. Based on multiple trials involving patients with hematologic disorders and those undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, the American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews recommend prophylactic platelet transfusion when platelet counts are less than 10 × 103 per μL, or at higher counts with signs of bleeding.50–53 One unit of platelets is expected to increase the platelet count in adults by 30 to 40 × 103 per μL.49

ACTIVITY PARTICIPATION

The 2016 American College of Sports Medicine guidelines recommends that for patients with platelet counts from 20 to 50 × 103 per μL, exercise should be limited to resistance training using elastic bands, stationary cycling, range-of-motion exercises, and walking. Vigorous exercise, contact sports such as boxing and football, and activities with increased trauma risk such as gymnastics are contraindicated with platelet counts less than 50 × 103 per μL.54

For patients with platelet counts between 10 and 20 × 103 per μL, strength training without weights and cardiovascular exercise without strain are recommended. The Seattle Cancer Care Alliance recommends only walking for their patients with platelet counts less than 20 × 103 per μL.55

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Gauer and Braun.56

Data Sources: A search was completed in OvidSP, PubMed, Essential Evidence Plus, Cochrane Library, and UpToDate using the key words activity participation, antiphospholipid syndrome, bleeding risk, COVID-19, chronic liver disease, thrombocytopenia in critically ill patients, drug-induced immune microangiopathy, drug-induced thrombocytopenia, etiologies, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, hemolytic uremic syndrome, hereditary thrombocytopenias, immune thrombocytopenia, incidence, invasive procedures, platelet transfusion, prevalence, prognosis, pseudothrombocytopenia, thrombotic microangiopathy, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, and vaccine-induced immune thrombotic thrombocytopenia. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, and organizational clinical practice guidelines. Search dates: June 28, 2021; July 22, 2021; August 21, 2021; September 21, 2021; December 10, 2021; December 16, 2021; and May 30, 2022.

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the U.S. Department of the Army, U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.