Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(4):397-404

Patient information: See related handout on endometriosis, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Endometriosis is an inflammatory condition caused by the presence of endometrial tissue in extra-uterine locations and can involve bowel, bladder, and all peritoneal structures. It is one of the most common gynecologic disorders, affecting up to 10% of people of reproductive age. Presentation of endometriosis can vary widely, from infertility in asymptomatic people to debilitating pelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, and period-related gastrointestinal or urinary symptoms. Diagnosis of endometriosis in the primary care setting is clinical and often challenging, frequently resulting in delayed diagnosis and treatment. Although transvaginal ultrasonography is used to evaluate endometriosis of deep pelvic sites to rule out other causes of pelvic pain, magnetic resonance imaging is preferred if deep infiltrating endometriosis is suspected. Laparoscopy with biopsy remains the definitive method for diagnosis, although several gynecologic organizations recommend empiric therapy without immediate surgical diagnosis. Combined hormonal contraceptives with or without nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are first-line options in managing symptoms and have a tolerable adverse effect profile. Second-line treatments include gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor agonists with add-back therapy, GnRH receptor antagonists, and danazol. Aromatase inhibitors are reserved for severe disease. All of these treatments are effective but may cause additional adverse effects. Referral to gynecology for surgical management is indicated if empiric therapy is ineffective, immediate diagnosis and treatment are necessary, or patients desire pregnancy. Alternative treatments have limited benefit in alleviating pain symptoms but may warrant further investigation.

Endometriosis is one of the most common gynecologic disorders, affecting up to 10% of patients of reproductive age,1 or approximately 5 million to 10 million people in the United States.2,3 The prevalence of endometriosis may be higher because definitive diagnosis requires surgical visualization, which all patients might not pursue.4 The prevalence ranges from 2% to 11% among asymptomatic patients and increases to 5% to 50% among patients presenting with infertility. Among symptomatic adolescents with dysmenorrhea, the prevalence of endometriosis is estimated at 50% to 70% for those with chronic pelvic pain and up to 75% for those with pain unresponsive to medical treatment.1 Data for population distributions, disease manifestations, and risk factors are limited to patients who are successfully diagnosed, which may introduce bias related to access to care.1

Etiology

Endometriosis is defined by the presence of endometrial glands and stroma in extrauterine locations. It is an inflammatory, estrogen-dependent condition associated with pelvic pain and infertility.5 Endometriosis involves a complex interaction between various endocrine, immunologic, inflammatory, and proangiogenic processes.4 Additional molecular mechanisms allow endometrial cells to adhere to peritoneal surfaces, proliferate, and develop into endometriotic lesions.4 Estrogen promotes implantation of endometrial tissue through proliferative and antiapoptotic effects in endometrial cells and stimulates local and systemic inflammation.6 Pain from endometriosis is elicited by localized immune and inflammatory responses. Neurogenesis, which is indicated by high levels of nerve growth factors that alter and increase sensory and sympathetic nerve fibers, is observed in endometriotic tissue.7,8 Nerve fiber entrapment within endometriotic lesions may explain associated sacral radiculopathy. Finally, central sensitization may cause endometriosis-induced neuropathic changes that decrease inhibition pathways.8,9

Risk Factors

Endometriosis is influenced by genetic and environmental factors (Table 1).1,4 There is a strong familial component to endometriosis shown by genetic studies that indicate increased frequency of disease in close relatives.10–12 Twin studies have estimated heritability of endometriosis at approximately 50%.12 Increased burden with common genetic variants is associated with more severe disease.11,12 Environmental factors such as diet, environmental contamination, and in utero hormonal exposures that may affect genetic expression are thought to explain more than one-half of disease liability.12 These risk factor associations suggest critical periods of exposure in utero and in early childhood that affect later development of endometriosis. Childhood and adolescent risk factors include early menarche and lower body mass index. In adulthood, risk factors include shorter menstrual cycles and nulliparity. There is inconsistent evidence for any relationship between physical activity, alcohol use, caffeine intake, or skin sensitivity and endometriosis.1

| Category | Probable risk factors |

|---|---|

| Adult | Increased menstrual flow, low body mass index, nulliparity, short menstrual cycles |

| Childhood and adolescence | Early menarche, low body mass index |

| Genetic | First-degree relative with endometriosis |

| In utero/early childhood | Diethylstilbestrol exposure, low birth weight, prematurity |

Diagnosis

HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

The diagnosis of endometriosis in primary care is clinical and should be based on history and physical examination findings. Patients with endometriosis typically present during their reproductive years with pelvic pain, infertility, or an ovarian mass (Table 2).13 The peak prevalence of endometriosis occurs in people 25 to 35 years of age. Endometriosis can be a diagnostic and clinical challenge, with many patients experiencing delays in diagnosis of up to four to 10 years.14 This delay can lead to disease progression and decreased quality of life15 and reinforces the importance of having a high clinical suspicion based on history. The diagnosis should also be considered in transgender and nonbinary patients or any persons with a uterus (Table 3).16,17

| Suspect endometriosis in patients (including those younger than 18 years) presenting with one or more of the following symptoms: |

| Chronic pelvic pain |

| Deep pain during or after sexual intercourse |

| Infertility |

| Period-related or cyclical gastrointestinal symptoms, especially painful bowel movements |

| Period-related or cyclical urinary symptoms, especially blood in urine or pain passing urine |

| Period-related pain affecting daily activities and quality of life, such as missing work or school |

| Symptom | Selected alternative diagnoses |

|---|---|

| Adnexal masses | Benign and malignant ovarian cysts, hydrosalpinx |

| Bowel symptoms (constipation, cramping, diarrhea) | Hemorrhoids, irritable bowel syndrome |

| Defecation pain (dyschezia) | Anal fissures, pelvic floor disorders |

| Dysmenorrhea | Adenomyosis, primary dysmenorrhea In adolescents, obstructed müllerian anomalies |

| Dyspareunia | Infectious vaginitis or cervicitis, pelvic floor disorders, psychosocial issues, vaginal atrophy, vulvodynia |

| Dysuria | Painful bladder syndrome, urinary tract infection |

| Infertility | Anovulation; cervical, tubal, structural, or infectious pathology; luteal phase deficiency; male factor infertility; unexplained subfertility |

| Nonmenstrual abdominopelvic pain | Abdominal wall nerve entrapment syndrome, adhesions, irritable bowel syndrome, migraine variant, neuropathic pain, pelvic congestion syndrome, sexually transmitted infection |

In a large case-control study in the United Kingdom, 73% of patients with endometriosis had abdominopelvic pain, dysmenorrhea, or menorrhagia compared with 20% of patients without endometriosis.18 The Visanne Post-approval Observational Study evaluated 27,840 participants from six European countries and found the most frequently reported symptoms associated with endometriosis were painful periods (62%), heavy/irregular bleeding (51%), and pelvic pain (37%).19

Physical examination should include a pelvic examination that checks for tenderness or nodules of the cul-desac or uterosacral ligaments, tenderness of the adnexa, tubo-ovarian masses, rectovaginal septum induration, and the presence of a fixed retroverted uterus.16 However, a normal physical examination does not rule out endometriosis.20

The definitive method of diagnosing endometriosis is considered to be laparoscopy with biopsy, which allows histologic confirmation of suspicious lesions.21 However, many societies, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, endorse the treatment of symptoms before obtaining a definitive diagnosis from surgery.22 There has been a paradigm shift away from surgical diagnosis to clinical diagnosis with technologic advancements in imaging to prevent delays in treatment.23,24

LABORATORY STUDIES AND IMAGING

Transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) is recommended as the initial imaging approach in patients with suspected endometriosis because it is widely available.25,26 Standard TVUS has demonstrated a specificity greater than 85% for all deep pelvic endometriosis sites, with sensitivity ranging between 50% (bladder, vaginal wall, and rectovaginal septum) and 84% (rectosigmoid). TVUS guided by bladder site tenderness—a modified technique in which particular attention is paid to tender points experienced by patients under gentle pressure of the ultrasound probe when specifically evaluating the bladder—had a sensitivity and specificity of 97.4%.26 If there is concern for deep infiltrating endometriosis involving the bowel, bladder, or ureter, then magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis (and abdomen, if indicated), typically without contrast media depending on the clinical scenario, is preferred, although it does have a higher cost than TVUS.21,22,25

Medical Treatment

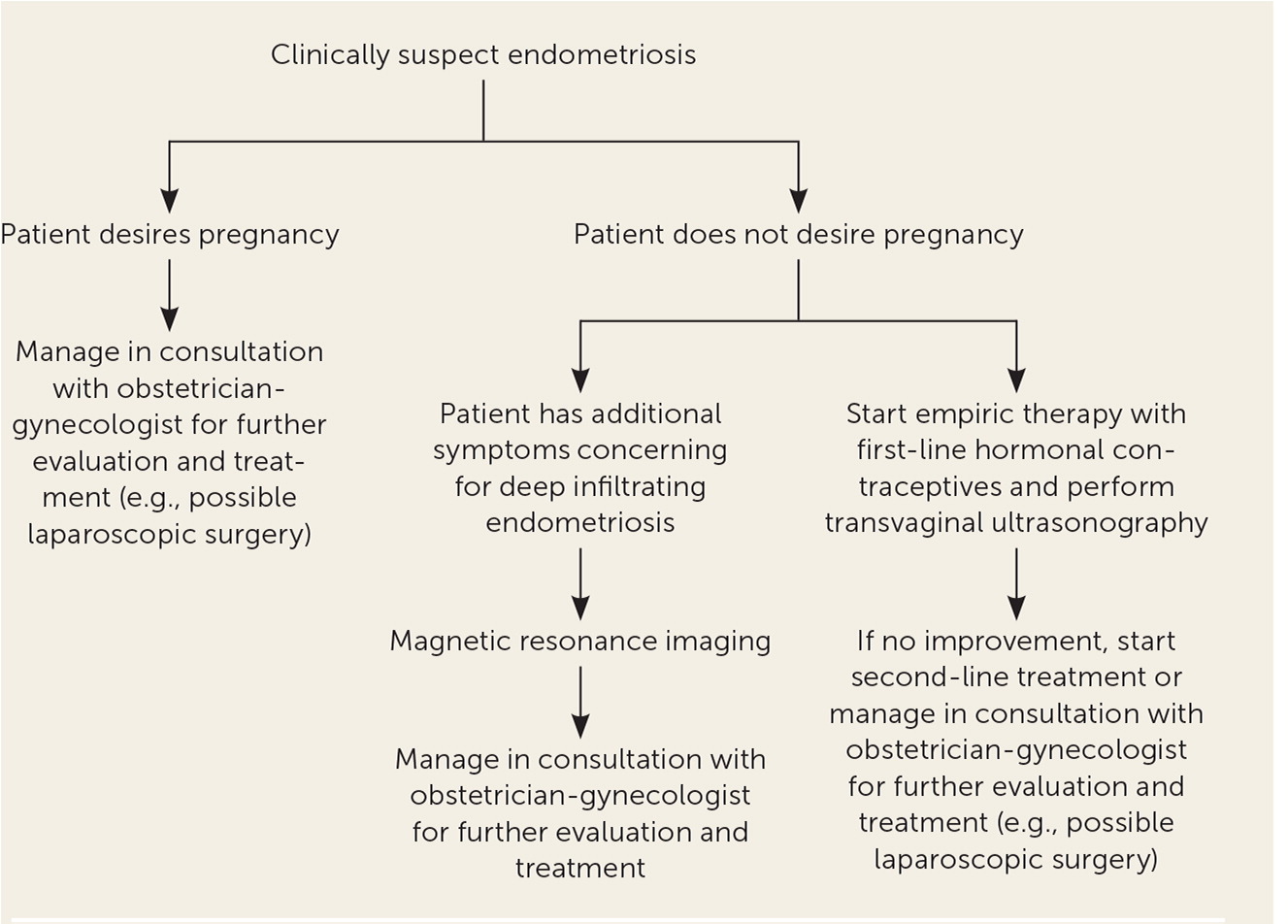

Endometriosis is a chronic disease that requires sustained treatment. Medical treatments are considered suppressive, with the main goal of preventing recurrence and reducing symptoms.16 A systematic review found that 17% to 34% of treated patients had symptom recurrence within 12 months of follow-up. The review also indicated that severity of disease may increase the risk of recurrence.27 Medication management should be individualized by considering factors such as age, predominant symptoms, pain severity, reproductive plans, extent of disease, medication adverse effects, and cost. Figure 1 is an algorithm for the evaluation and management of endometriosis in primary care.13

Hormonal therapy is the mainstay of treatment and focuses on suppressing estrogen, inhibiting tissue proliferation, and reducing inflammation.4,16 Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are effective for primary dysmenorrhea and can be offered as an initial treatment in conjunction with hormonal contraceptives.28 However, a 2017 Cochrane review found insufficient evidence that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs significantly reduce endometriosis-related pain.29,30

Combined hormonal contraceptives, including oral pills, transdermal patches, and vaginal rings, are considered first-line therapies.4,8,22 For patients with severe or refractory symptoms or contraindications to combined hormonal contraceptives, alternative hormonal therapies can be considered (Table 46,16,25,28,31–34). Hormonal treatments are often continued until pregnancy is desired or the patient reaches the average age of menopause, when symptoms often improve with the decrease of estrogen levels.28

Several randomized controlled trials have shown that combined hormonal contraceptives are effective in providing pain relief and prevention of postoperative recurrence. Combined hormonal contraceptives suppress ovarian activity and lead to decidualization of endometriotic tissue to slow progress of the disease. Treatment regimens can be cyclical or continuous without using placebo pills, but studies have shown that continuous therapy results in better pain control.31

Progestin-only methods (i.e., oral, depot, implant, or hormonal intrauterine systems) are other first-line options that may be considered for those who cannot tolerate or have contraindications to estrogen.16 Progesterone inhibits ovulation, induces decidualization of the endometrium, alters estrogen receptors, and decreases growth of endometriotic lesions. Studies show overall effectiveness in relieving pelvic pain and dysmenorrhea.31 Using a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system is associated with fewer painful symptoms and higher patient satisfaction, but this option does not help with treating ovulation pain because it does not suppress ovulation.8 Table 4 lists common adverse effects.6,16,25,28,31–34

| Class | Mechanism | Drug | Characteristics | Adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-line treatments | ||||

| Estrogen-progestin combination (combined oral contraceptives, patch, ring) | Decidualization or atrophy of lesions Inhibition of ovulation | Monophasic estrogen-progestin (continuous use daily) | Inexpensive Temporary relief Decreases pain by 52% Continual use to decrease recurrence if pain after excision | Amenorrhea, breakthrough bleeding, breast tenderness, headaches, mood changes, nausea, weight gain |

| Progestins (oral, depot injection, implant, intrauterine device) | Decidualization or atrophy of lesions Inhibition of angiogenesis | Norethindrone acetate (oral) Medroxyprogesterone acetate (intramuscular) Etonogestrel-releasing implant Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system | Inexpensive Temporary relief Decreases deep dyspareunia | Acne, breakthrough bleeding, breast tenderness, headache, mood changes, weight gain |

| Second-line treatments | ||||

| GnRH receptor agonists | Inhibition of gonadotropin secretion and subsequent downregulation of pituitary GnRH receptors causing hypoestrogenic state | Leuprolide depot (Lupron) Goserelin (Zoladex) Nafarelin (Synarel) Add-back therapy: norethindrone acetate, 5 mg, plus vitamin D plus calcium; monophasic combined oral contraceptive, conjugated equine estrogen, 0.625 mg daily; or transdermal estradiol, 25 mcg daily | Expensive Temporary relief Limited use up to one year with add-back therapy Improves pain 60% to 100% | Atrophic vaginitis, decreased bone mineral density, hot flashes, mood changes |

| GnRH receptor antagonists | Inhibition of gonadotropin secretion by competitive binding and subsequent downregulation of GnRH receptors causing hypoestrogenic state | Elagolix (Orilissa; oral) Two dosing regimens: 150 mg daily up to 24 months, or 200 mg twice daily up to six months | Expensive Higher-dose therapy use limited to six months due to risk of bone density decline Contraception recommended because patients can still ovulate; contraception can also be used as add-back therapy Improves dyspareunia and dysmenorrhea | Decreased bone mineral density, hot flashes, lipid abnormalities, mood changes, vaginal dryness |

| GnRH receptor antagonist plus combination hormone therapy (estradiol and norethindrone) | Relugolix/estradiol/norethindrone (Myfembree) Once daily dosing of combination tablet containing relugolix, 40 mg/estradiol, 1 mg/norethindrone, 0.5 mg up to 24 months | One tablet containing combination hormones to prevent hypoestrogenic adverse effects (i.e., bone loss, hot flashes) and limit endometrial effects from unopposed estrogen Use of nonhormonal contraception recommended | FDA boxed warning: increased risk of thrombotic or thromboembolic disorders due to estradiol Contraindicated in patients older than 35 years who smoke and those with uncontrolled hypertension, hormone-sensitive malignancy, pregnancy, hepatic impairment/disease Risk of bone loss, mood changes, uterine fibroid prolapse or expulsion, alopecia, elevated transaminase levels, increased cholesterol, decreased glucose tolerance | |

| Androgenic steroid | Inhibition of ovarian enzymes Inhibition of pituitary gonadotropin secretion Local growth inhibition | Danazol (oral or vaginal daily) | Established effectiveness from long-standing experience in endometriosis treatment | Acne, hair loss, hirsutism, weight gain |

| Aromatase inhibitors (reserved for severe disease) | Local blockade of aromatase conversion of androgens to estrogens | Letrozole (Femara; oral daily) Anastrozole (Arimidex; oral daily) | Use when other therapies have failed Limited duration Not approved by the FDA | Decreased bone mineral density, headaches, hot flashes, myalgia |

Second-line treatment options include gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) receptor agonists with add-back therapy, GnRH receptor antagonists, and danazol. Aromatase inhibitors are reserved for severe disease. These treatments have been shown to be as effective as combined hormonal contraceptives or progestin-only methods, but they often cause bothersome adverse effects.16,29 Although initial administration of GnRH receptor agonists triggers the release of follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone, chronic use causes downregulation of pituitary GnRH receptors, resulting in estrogen deficiency and regression of endometriotic lesions.4,16,31 Adverse hypoestrogenic effects include headache, hot flashes, loss of bone mineral density, mood changes, and vaginal dryness.8,29 Use of GnRH receptor agonists should not exceed six months because of these potential adverse effects. Add-back therapy using high-dose progestin alone (norethindrone acetate, 5 mg orally per day) or low-dose combined estrogen and progestin can mitigate adverse effects and allow for extended treatment courses up to one year.8,31 Specifically, add-back therapy reduces vasomotor symptoms, preserves bone mineral density, and helps improve compliance. Using higher doses of estrogen to treat adverse effects should be limited because estrogen can restimulate growth of endometriotic lesions.

GnRH antagonists are a newer, promising category of treatments that inhibit GnRH signaling by binding competitively to GnRH receptors. They produce immediate effects and do not cause the initial flare-up of stimulating GnRH and the resulting surge in follicle-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone that occur with GnRH agonists. GnRH antagonists induce a dose-dependent hypoestrogenic state, resulting in a better adverse effect profile.31 They improve dysmenorrhea and nonmenstrual pelvic pain and allow for titration to balance effectiveness and tolerability.6 GnRH antagonists are available in oral and injectable formulations. Oral elagolix (Orilissa) is the first U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved GnRH antagonist for treating endometriosis. Once-daily oral relugolix combination therapy containing estradiol and progestin (Myfembree) has also been approved for treatment of moderate to severe endometriosis-associated pain. Linzagolix is currently in clinical trials with favorable data showing effectiveness in pain management with similarly favorable adverse effect profiles.33,35–37 Adverse effects of treatment are listed in Table 4.6,16,25,28,31–34 Add-back therapy may be used to counter hypoestrogenic effects. It should also be noted that elagolix and relugolix combination therapy do not suppress ovulation, and patients should be counseled to use contraception.6

Danazol is an androgenic agent that increases free testosterone levels and inhibits pituitary gonadotropin secretion and ovarian enzymes, reducing estrogen production. It has been shown to treat endometriosis-related pain, but it is not commonly used because of bothersome androgenic adverse effects.17,28

Aromatase inhibitors are reserved for patients with severe, refractory, endometriosis-related pain. Aromatase inhibitors are used off-label to regulate estrogen formation within endometriotic lesions. Studies have shown greater improvement of pain symptoms compared with progestin alone or GnRH receptor agonists alone.31,38 Adverse effects can include bone loss with prolonged use and development of ovarian follicular cysts. Aromatase inhibitors are often prescribed in combination with a GnRH receptor agonist or combined oral contraceptive to downregulate the ovaries and suppress follicular development.16,28,31

Surgical Treatment

Surgical management is indicated if empiric therapy is ineffective, if medical management is not tolerated, or to immediately diagnose and treat the patient, as in the case of an adnexal mass or treatment of infertility.16 From a cost perspective, surgical management after failure of three medications may be the most cost-effective approach; further delay may increase cost and decrease quality of life.39

Surgical excision of endometriotic tissue for treatment of pain was thought to be effective. However, based on limited evidence, an updated Cochrane review reported uncertainty about whether laparoscopic surgery (i.e., excision or ablation of endometriotic lesions) improves endometriosis pain at six and 12 months compared with diagnostic laparoscopy alone.40 A systematic review of three randomized controlled trials comparing laparoscopic excision with laparoscopic ablation reported no clear statistical difference in pain scores after treatment, but there was a trend that favored excision.41 Excision of endometriomas is controversial. In a Cochrane review, excision of a cyst was associated with reduced rate of endometrioma recurrence, reduced symptom recurrence, and increased spontaneous pregnancy rates compared with ablative surgery.42 However, there have been reports that cystectomy may be detrimental to ovarian reserve and function.43 For patients with endometriosis who do not desire future pregnancy and in whom all medical treatments and conservative surgical management options have failed, a hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is effective in the treatment of pain.22,44 Patients with higher levels of centralized pain before undergoing a hysterectomy are more likely to experience refractory pain.45

Complementary and Alternative Treatments

Patients with endometriosis often ask about dietary changes or other interventions that might allow them to gain control of their symptoms. Alternative treatments for endometriosis such as acupuncture, exercise, and dietary changes may help improve pain symptoms, although there is limited evidence to support these alternatives. A meta-analysis of acupuncture treatment showed a reduction in pelvic pain compared with placebo (P = .007); acupuncture treatments varied from once weekly for five weeks to twice weekly for eight weeks.46 A systematic review showed inconclusive evidence regarding the effects of physical activity and exercise on symptoms of endometriosis.47 An observational study evaluating dietary changes in patients with endometriosis found that some dietary modifications (e.g., avoidance of gluten or dairy) reduced perceived pain symptoms without identifying any association between diet and improvement in quality of life.48 Another systematic review showed limited evidence of nutrient supplements improving symptoms of endometriosis.49

Management of Infertility

Infertility is likely related to inflammation and damage to fallopian tubes and ovaries from scar tissue.50 Patients with infertility do not benefit from diagnostic laparoscopy any more than patients with other symptoms of endometriosis,44 although once infertility has been established and the patient desires pregnancy, laparoscopic surgery is an effective treatment for minimal to mild disease. In those with mild disease, laparoscopic surgery may improve spontaneous pregnancy and live birth rates compared with expectant management.40,50,51 No randomized controlled trials have determined whether clinical pregnancy rates are improved with laparoscopic surgery in patients with moderate to severe endometriosis.16,52 Patients with advanced maternal age, low ovarian reserve, male factor infertility, or a combination of these should consider immediate in vitro fertilization rather than surgical intervention.16 A review of 12 randomized controlled trials reported no evidence that ovulation suppression with hormonal treatments for up to six months before attempted conception results in increased pregnancies compared with placebo in patients who wished to conceive.53

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Schrager, et al.13

Data Sources: We searched Essential Evidence Plus, PubMed, Google Scholar, and the Cochrane database, using the search terms endometriosis, etiology of endometriosis, epidemiology of endometriosis, treatment of endometriosis, infertility associated with endometriosis, acupuncture and endometriosis, nutrition and endometriosis, and alternative treatment and endometriosis. Search dates: September to November 2021 and May to June 2022.