Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(5):543-548

Related letter to the editor: Helmet and Pad Removal for Football Head and Neck Injuries

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Although rare, sport-related injuries to the head and neck can be life threatening; therefore, timely and appropriate treatment is critical. Preparation is key for the sideline physician and begins well before arriving on the sideline. Knowing the athletic trainer and support staff, establishing a chain of command and emergency action plan, and having all the appropriate equipment readily available are important for game or practice preparedness. At the athletic event, physicians should have a clear line of sight to the field of play and easy access to reach the field when necessary. When performing an on-field assessment of any athlete who is not moving, whether conscious, unconscious, or with decreased consciousness, head and neck injury must be assumed, and the injured athlete should be placed on a spine board with cervical spine stabilization and transported to the emergency department for further evaluation. Generally, helmets and pads are left on while the injured athlete is being transported. Concussion is among the most common head and neck injuries in athletes, and if concussion is suspected, the athlete cannot return to the game on the same day. Nasal fractures do not always require immediate closed reduction; however, orbital, maxillary, or mandibular fractures require transport to the emergency department. For tooth avulsion, time is important; reimplantation should be attempted within 30 minutes of injury.

Head, neck, and cervical spine injuries are common in athletes of all ages, and the incidence seems to increase with age.1,2 Soft tissue injuries such as neck sprains and strains or facial lacerations are much more common than vertebral fractures and spinal cord injury.1–3 Many of these injuries are self-limited and can be managed on the sideline or in the training room.3 Although catastrophic cervical spine injuries are uncommon, they are associated with significant morbidity and mortality and can have significant lifetime costs.4 When an athlete appears to be injured, the sideline physician must be prepared to provide a focused assessment and treatment plan.

Preparation

Before being on the sideline at a game or practice, it is important to be as prepared as possible in the event of any injury. When covering games at the high school level or higher, athletic trainers are typically present at most games and practices. Many times, they will be the first point of contact if an athlete is injured, and sideline physicians should at least make a quick introduction before the game or practice to establish a plan in the event of any athlete injury.5 Knowledge of the closest trauma center, available resources such as the venue’s emergency action plan, and location of an automated external defibrillator (AED) and spine board are critical. During the game or practice, the sideline physician should have a clear, unobstructed view of the field of play and quick, easy access to the field, if needed.6 Access to a treatment room, where more detailed evaluation and treatment can be administered, should be made available when appropriate and feasible.6 Awareness of supplies available in the athletic trainer bag and training room to assess injured athletes is critical. Examples of supplies include an eye kit, flashlight, and nasal packing material. A more complete list of supplies is provided by a consensus statement on sideline preparedness from several organizations including the American Academy of Family Physicians.7

Neck Injuries

The initial evaluation of an injured athlete with suspected head or neck trauma should include assessment of airway, breathing, circulation, disability, and exposure according to the principles of Advanced Trauma Life Support.3,6,8 This should be followed by a spine evaluation and neurologic assessment using the Glasgow Coma Scale.5

Any athlete not moving, whether conscious, unconscious, or with decreased consciousness, should be considered to have a cervical spine injury3,8 (Table 15,9–11). The cervical spine should be stabilized, and the athlete transferred to a spine board using the log roll or lift and slide maneuver (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AlwFLh36kiE). These maneuvers involve rolling the athlete to the side and transferring them onto the spine board; alternatively, the athlete should be lifted and slid onto the spine board with assistance from trained personnel such as athletic trainers.5,8,12,13 The sideline physician is usually at the head of the athlete providing cervical spine stabilization and providing instruction to other clinicians assisting in stabilizing the athlete.5,8,12,13 The athlete should then be transported to the emergency department by emergency medical services (Table 23,5,8,10–14). In sports such as football and hockey where the athletes are wearing helmets and pads, it is recommended to leave the equipment in place during transfer.5,8,13 If there is altered mental status or an airway needs to be established, the face mask can be removed.5,8 If either the helmet or pads need to be removed, both should be removed together to avoid causing any cervical hyperflexion or hyperextension, and this should be performed by a team of trained personnel comprising at least two or three additional people.5,8 For a demonstration of helmet and pad removal, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HdyGMUJfWWw.

| Bilateral symptoms |

| Decreased consciousness or unconscious athlete |

| Focal tenderness to palpation over cervical spine |

| Paralysis |

| Restricted or apprehensive cervical range of motion |

| Severe neck pain |

| Acute vision changes |

| Cervical spine injury |

| Facial laceration with underlying fracture |

| Hyphema |

| Mandibular fracture |

| Maxillary fracture |

| Orbital fracture |

Stingers and Burners

Stingers are traumatic stretch injuries of one or more cervical nerve roots or the brachial plexus causing a transient neurapraxia,10 most commonly involving the C5 and C6 nerve roots. Symptoms include unilateral upper extremity burning or paresthesia with associated motor weakness in the absence of cervical pain or limited cervical motion that may last from minutes to hours.11,12,15 In some cases, symptoms can take up to two weeks to completely resolve.11,15

It is important to differentiate stingers from more serious cervical spine injuries such as cervical cord neurapraxia, which involves paresthesia in more than one extremity and should be treated with cervical spine stabilization, spine board transfer, and transport to the emergency department.

If the athlete does not have bilateral symptoms, has complete resolution of symptoms within five minutes, has a normal neurologic examination, and demonstrates full range of motion and strength, there is a possibility of returning to play in the same game or practice at the sideline physician’s discretion.15,16 All other cases require evaluation for underlying injury or pathology before permitting return to play once symptoms have resolved.16 Athletes with recurrent stingers have a high risk of underlying pathology and require evaluation and imaging.11

Head Injuries

With the advent of helmet use in many sports, there has been a noticeable decrease in the incidence of serious and fatal head injuries such as skull fractures, subdural hematomas, and facial injuries.17,18 However, this has not completely eliminated head injuries because not all sports require helmet use, and injuries such as concussion cannot be prevented by helmets or other protective equipment.

Concussion

A sport-related concussion is a traumatic brain injury induced by biomechanical forces.19 It can involve a direct blow to the head or neck or a blow anywhere on the body that transmits an impulsive force to the head. There can be associated short-lived neurologic impairment.19 Concussion is among the most common head and neck injuries in athletes.20 If a concussion is suspected, the athlete should be removed immediately from the field of play and should not return to play on the same day.19 Focused rapid assessment can be done on the sideline or in a treatment room. Assessment involves neuropsychological testing and postural stability testing.19 Sideline assessment tools, such as the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool, 5th edition (https://scat5.cattonline.com), are commonly used to assist in making the diagnosis. Athletes should undergo a graduated return to physical activity. Further detailed information on concussion can be found in a previous American Family Physician article19 and at https://www.cdc.gov/headsup/providers/index.html.

Lacerations

Lacerations are the most encountered facial injury in child athletes, but the incidence has decreased with the use of full facial protection.2,3,14,21 After checking airway, breathing, and circulation to assess if the patient is stable or unstable, a quick determination should be made about whether the injury can be managed in the training room or requires treatment in an emergency department setting. Hemostasis should be obtained by applying direct pressure with two fingers on the wound, and all facial lacerations should be irrigated with sterile saline and carefully examined for the presence of foreign bodies.10,14 Suture closure of a simple laceration is recommended for planned in-game return because there is less chance of the wound reopening; otherwise, surgical adhesives may be used if the athlete will not return to play.14,21 For scalp lacerations, closure with staples is appropriate.3 Lacerations of the eyelid, vermilion border of the lips, and helical rim of the ear should be sutured by an experienced clinician to prevent poor outcomes.10 Facial lacerations should be carefully investigated for any underlying fracture or nerve injury (commonly the facial and trigeminal nerves). If there is a facial laceration with underlying fracture, it should be covered with a moist gauze, and the patient should be transported to the emergency department for further treatment14 (Table 23,5,8,10–14).

Facial Fractures

Nasal bone fractures are the most common sport-related facial fracture.10,14 Immediate closed reduction of a grossly deformed nose is not always necessary and should be done only if there is a possibility of airway compromise and if the sideline physician has training in this type of closed reduction.14 There may be concurrent epistaxis, and this can be treated with direct pressure, packing, and nasal decongestant spray.10 Orbital bone, mandibular, and zygoma fractures can also occur but are less common than nasal bone fractures. Orbital fractures should include checking for signs of infraorbital hypoesthesia, decreased extraocular movements, and diplopia (Table 312,14). Any suspected orbital fracture requires emergency care. Maxillary fractures may present with a step off on palpation of the palate. For mandibular fractures, the sideline physician should have the athlete bite down to check for malocclusion. There can be airway compromise with mandibular fractures, and patients require monitoring until stabilization.10,14 The presence of maxillary or mandibular fracture would require transportation to the emergency department for further treatment by a specialist10,14 (Table 23,5,8,10–14 ).

| Asymmetric perception of light brightness |

| Blood or clot in anterior chamber |

| Decreased extraocular movement (especially when looking up) |

| Diplopia |

| Infraorbital hypoesthesia |

| Irregular pupil |

| Reduced vision |

When evaluating for facial fractures in the field, initial steps include palpating bony prominences bilaterally, comparing the height of zygoma bones, and checking for facial asymmetry.14 Having a systematic approach to palpation can help avoid missing any subtle injuries. The order of palpation should be: supraorbital and lateral orbital rims, infraorbital rims, zygoma, zygomatic arches, nasal bones, maxilla, and mandible.14

Eye Injury

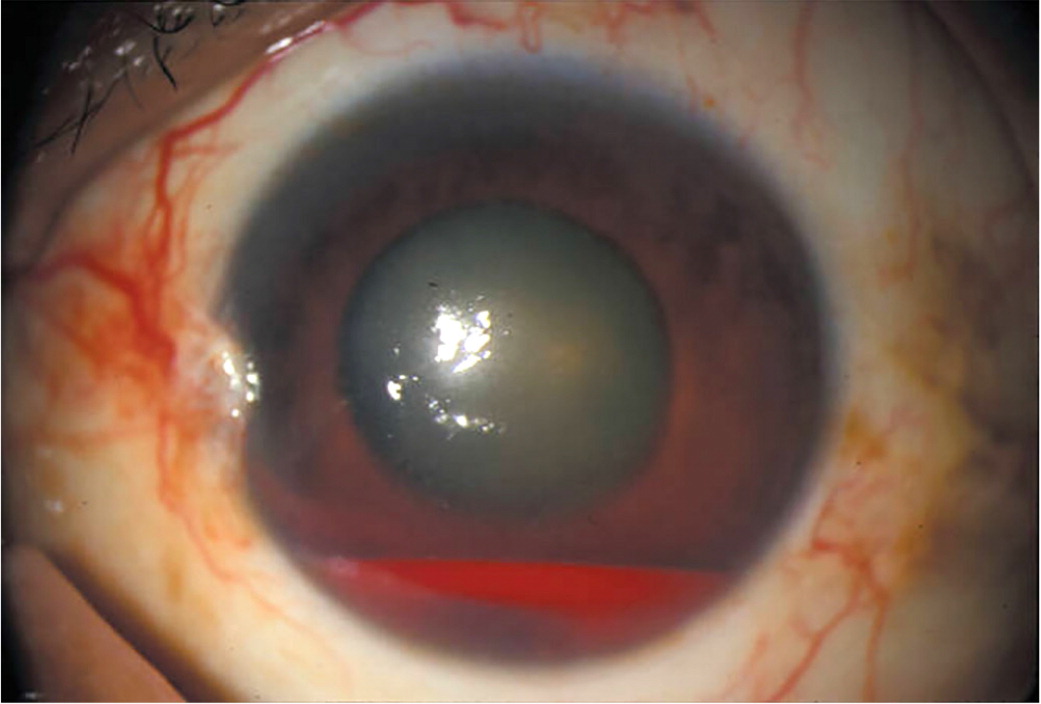

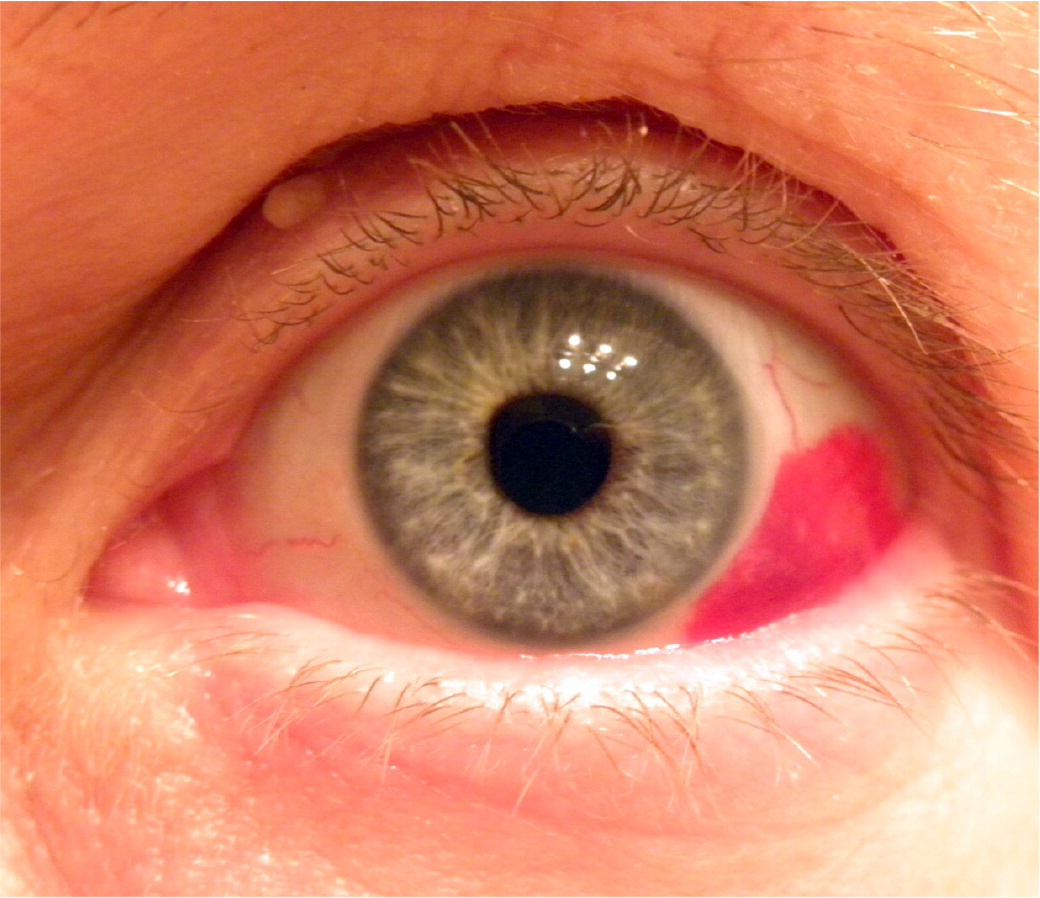

Suspected orbital or retinal injuries require careful examination with a light source such as a flashlight. After initial examination for swelling, laceration, and orbital rim step off, the sideline physician should also do a visual acuity test, check pupillary size and response, and check visual fields.10,14 The athlete should be asked if the light is brighter in one eye compared with the other because this can be a sign of optic nerve injury.10 Traumatic hyphema (Figure 122), or blood in the anterior chamber, is a common complication of blunt or penetrating injury to the eye and can result in permanent vision loss.12 Athletes with hyphema require immediate transportation to the emergency department. Hyphema should be differentiated from subconjunctival hemorrhage (Figure 223), which involves conjunctival blood vessel rupture and spares the anterior chamber of the eye. Because subconjunctival hemorrhage is usually self-limited and resolves in seven to 10 days, athletes can usually return to the field if they have no vision changes.12

Athletes presenting with sharp tearing pain or sensation of a foreign body in their eye may have a corneal abrasion. If the athlete is wearing contact lenses, they should be removed, and the athlete can return to play if they can safely manage without corrective lenses.12 If there is evidence of red flags such as vision changes, decreased pupillary response to light, or an irregular pupil, the athlete should be transported to the emergency department for further evaluation12 (Table 23,5,8,10–14 and Table 312,14). During transport, the patient’s head should be kept still and the affected eye covered with a cup or shield, being careful to avoid any pressure on the globe.10,12 Required use of appropriate ocular protection can significantly decrease the incidence of traumatic eye injury during athletic activity.

Dental Injuries

Although mouthguards reduce the incidence of dental injuries, such injuries can still occur even with mouthguard use.10,12,14 If there is a tooth avulsion, the tooth should be handled by the crown to avoid damaging the root.10,12 The avulsed tooth should be rinsed with sterile saline and reimplanted in the socket and stabilized by having the athlete gently bite down on overlying gauze.10,12 Alternatively, the tooth can be transported in milk, a balanced salt solution, or saliva. If the tooth cannot be reimplanted, the athlete can return to play in 48 hours; if the tooth is reimplanted, return to play should be delayed two to four weeks.12 Tooth reimplantation must be done as quickly as possible because reimplantation within 30 minutes results in 90% or greater tooth survival, whereas a two-hour delay in reimplanting has a less than 5% probability of tooth survival.10,12

Data Sources: The Cochrane database, PubMed clinical query, Essential Evidence Plus, Clinical Evidence, and UpToDate were searched with the key words: sport head injuries, sport neck injuries, cervical spine athletic injuries, sport facial injuries, sport lacerations, spine board transfer, sideline injury management, athletic head injuries, and athletic eye injuries. Search dates: December 2021, January 2022, and July 2022.