Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(5):549-556

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

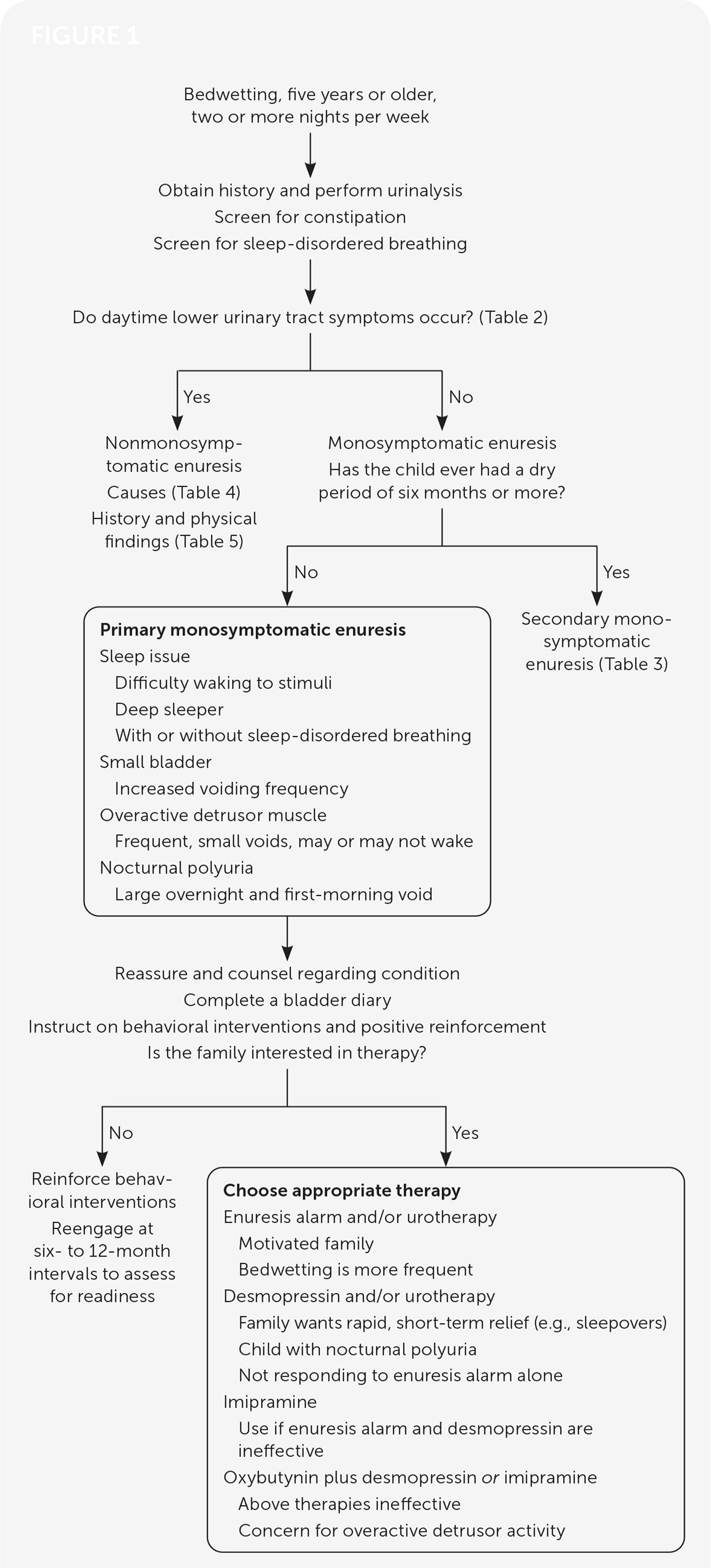

Nocturnal enuresis is defined as nighttime urinary incontinence occurring at least twice weekly in children five years and older. Approximately 14% of children have spontaneous resolution each year without treatment. Subtypes of nocturnal enuresis include nonmonosymptomatic enuresis and primary and secondary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis. Monosymptomatic enuresis is characterized by nighttime bedwetting without daytime urinary incontinence. Pathophysiology of primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis may be due to sleep arousal disorder, overproduction of urine, small bladder storage capacity, or detrusor overactivity. Children with nonmonosymptomatic enuresis have daytime and nighttime symptoms resulting from a variety of underlying etiologies. An in-depth history is an integral component of the initial evaluation. For all types of enuresis, a comprehensive physical examination and urinalysis should be performed to help identify the cause. It is important to reiterate to the family that bedwetting is not the child’s fault. Treatment should begin with behavioral modification, which then progresses to enuresis alarm therapy and oral desmopressin. Enuresis alarm therapy is more likely to produce long-term success; desmopressin yields earlier symptom improvement. Treatment of secondary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis and nonmonosymptomatic enuresis should primarily focus on the underlying etiology. Pediatric urology referral should be made for refractory cases in which underlying genitourinary anomalies or neurologic disorders are more likely.

Nocturnal enuresis, defined as involuntary bedwetting at least twice weekly in children five years and older,1 affects 15% to 20% of children by five years of age.2 Children with enuresis have lower self-esteem, lower self-confidence, and decreased quality of life compared with children who do not have enuresis.3,4 Each year, 14% of children will experience spontaneous resolution, with sharp decreases in incidence among older children (1% to 2% by 17 years of age) and adults (0.5% to 1%), according to cross-sectional data.2 Severe enuresis (nightly, heavy wetting or daytime symptoms) is less likely to resolve spontaneously; early intervention is key to resolution.5 Treatment improves patients’ health-related quality of life scores, including self-esteem, emotional well-being, and relationships with friends and family.6 Familial disposition is the biggest risk factor for enuresis; children from families without a history of enuresis have an incidence of 15%, whereas children from families with a history of enuresis have a 44% and 77% likelihood of developing enuresis if one or both parents were enuretic, respectively.2 Enuresis tends to resolve in first-degree relatives at similar ages.1,7,8 Additional risk factors for nocturnal enuresis are listed in Table 1.9,10 This article addresses common questions about nocturnal enuresis.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Initial laboratory workup in children with enuresis should include a urinalysis.1,15 | C | Consensus statement and expert opinion |

| Daytime lower urinary tract symptoms and constipation should be treated before initiating nocturnal enuresis therapy.1,17 | C | Consensus statement and expert opinion |

| Children with enuresis and obstructive sleep apnea should be evaluated by a pediatric otorhinolaryngologist for consideration of adenotonsillectomy.25,26 | A | Good-quality meta-analysis and prospective cohort study |

| Enuresis alarm therapy is effective in the treatment of monosymptomatic enuresis in children.1,27 | A | Good-quality meta-analysis and randomized controlled trials |

| Desmopressin therapy is effective for the treatment of monosymptomatic enuresis in children but has a high relapse rate.28,29 | A | Good-quality meta-analysis and randomized controlled trials |

| Adenotonsillar hypertrophy |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder |

| Being male (affected twice as often as females) |

| Bladder dysfunction |

| Constipation |

| Daytime enuresis (diurnal enuresis) |

| Developmental delay |

| Emotional stress |

| Encopresis |

| Family history of nocturnal enuresis |

| Sleep deprivation |

What Is the Difference Between Monosymptomatic and Nonmonosymptomatic Nocturnal Enuresis?

Nocturnal enuresis can be divided into two subtypes: monosymptomatic, in which nighttime bedwetting is the only symptom, and nonmonosymptomatic enuresis, which includes the presence of daytime lower urinary tract symptoms with bedwetting1 (Table 21,11). Monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis can be subdivided into primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis, where there has never been six months of continuous dry nights, and secondary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis, where a period of six months of continuous nighttime dryness existed and then bedwetting recurred.1

| Dysuria |

| Frequency |

| Hesitancy |

| Incontinence |

| Low or high daytime voiding volumes (voiding fewer than four or more than seven times per day) |

| Straining to void |

| Urgency |

| Weak stream |

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis may be attributed to sleep arousal disorder, nocturnal polyuria, low bladder storage capacity, or detrusor overactivity. Children with sleep arousal disorders have a harder time waking in response to normal bladder cues. These children have more fragmented and nonrestorative sleep.12–14 Nocturnal polyuria and large volume voids are present when the kidneys do not concentrate urine appropriately. The formal evaluation of polyuria includes weighing sheets or diapers and measuring the first-morning void volume. Factors contributing to polyuria include drinking large volumes before bedtime; ingestion of large amounts of solute, such as salt or sugar; and decreased vasopressin release from the pituitary at night.1 Underlying bladder issues, including low bladder storage capacity and detrusor overactivity, may also cause enuresis.1 Secondary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis is more likely to have an underlying pathologic cause and may be the first sign of a new medical issue. Common causes of secondary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis2 are listed in Table 3.1,15,16

| Acute renal failure |

| Constipation |

| Diabetes insipidus |

| New-onset diabetes mellitus |

| Stress (e.g., addition of a new sibling, bullying, parental deployment, parental discord) |

| Urinary tract infection |

Nonmonosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis occurs in 15% to 30% of children with enuresis.17 It is usually attributed to an underlying pathologic cause; common causes are listed in Table 4.1,17 Diagnosis and treatment of the underlying pathology causing the daytime symptoms should occur before nocturnal enuresis therapy.17 Children with nonmonosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis have a higher incidence of comorbid psychological disorders, including attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, conduct disorder, developmental delay, oppositional defiant disorder, and separation anxiety.17–20

| Chronic kidney disease |

| Constipation |

| Diabetes mellitus |

| Overactive bladder |

| Spinal dysraphism |

| Underlying neurologic disorder |

| Urethral sphincter dysregulation |

| Urinary tract malformation |

| Urinary tract obstruction |

What Should Be Included in the Evaluation of Nocturnal Enuresis?

History and physical examination help guide the evaluation, treatment, and prognosis of nocturnal enuresis. The history helps differentiate between monosymptomatic and nonmonosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis and helps identify underlying comorbidities. The physical examination is usually normal in monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis but is helpful in differentiating the etiology of nonmonosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis. If nonmonosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis or secondary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis is suspected, a urinalysis should be performed to rule out urinary tract infections.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

In primary monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis, important initial questions in the history should evaluate readiness and motivation for change. How disruptive is enuresis to the child and family? How motivated is the family in working toward a resolution? Has the family tried positive reinforcement, scheduled waking, or withholding liquids at bedtime?21

The physician must assess the degree and frequency of bedwetting to help evaluate the severity of the enuresis. How frequent are the episodes (e.g., how many times per night, week, or month)? At what time of the night does the bed-wetting occur? Are the voids large or small? Does the child have a large first-morning void? Has the child ever had a six-month period of dry nights?1

A voiding chart (noting daytime lower urinary tract symptoms, daytime or nighttime incontinence for at least one week, and voiding volumes and fluid intake for two days) may be helpful in directing therapy and addressing secondary causes.1,11,15 The physician should ask about family stressors, areas of conflict with treatment, negative discipline techniques, and abuse.8

| Findings | Suggested conditions |

|---|---|

| Failure to thrive, growth delay, polydipsia, polyuria | Diabetes insipidus, diabetes mellitus, kidney disease |

| Allergic shiners, daytime somnolence, enlarged tonsils, gasping while sleeping, mouth breathing, snoring | Sleep apnea |

| Daytime lower urinary tract symptoms, enlarged bladder, labial adhesions, recurrent urinary tract infections, urethra abnormalities (hypospadias, meatal stenosis, phimosis) | Neurogenic bladder, structural abnormality, or urinary dysfunction Current symptoms of dysuria require immediate evaluation for possible urinary tract infection |

| Hard stools, infrequent stooling, stool ball | Constipation |

| Poor anal tone, sacral anomalies (lipoma above gluteal cleft, sacral dimple, tuft of hair) | Neurogenic bladder, spinal anomaly |

| Perianal excoriations, vulvovaginitis | Sexual abuse |

| Abnormal gait, lower extremity reflex abnormalities, lower limb hypo- or hypertonia, sensory deficits | Neurologic disorder |

| Difficulties with attention, global developmental delay, hyperactivity | Comorbid behavioral issue or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder |

What Are the First‐Line Treatments for Enuresis Once Secondary Causes Have Been Addressed?

First-line treatments include enuresis alarms and desmopressin. Behavioral modification is likely better than placebo, but it is more effective when used in conjunction with enuresis alarms. In nonmonosymptomatic enuresis, focus on underlying disorders before treating the enuresis. Enuresis alarms are most successful when families are motivated, and they provide a higher cure rate than when using desmopressin. The use of desmopressin is effective, but a high relapse rate occurs after discontinuation.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

It is important not to hold the family culpable in their child’s illness and to assess motivation for treatment.1 Behavioral modification modalities are reasonable options and may be offered when the family is not ready for a trial of other first-line therapies. They are beneficial when positive and reward focused and are possibly more effective than placebo.21,23,24 Effectiveness increases when used in conjunction with enuresis alarms.23 Behavioral modification such as basic bladder training (urotherapy) includes targeted fluid intake (30 to 50 mL per kg per day and avoiding drinking one to two hours before bedtime), timed bladder emptying every three hours while awake, proper positioning when voiding, and treating constipation.24 Patients with sleep-disordered breathing should be evaluated for possible adenotonsillectomy by a pediatric otorhinolaryngologist because nocturnal enuresis may partially or completely resolve after surgical intervention.25,26

Enuresis alarms are highly effective, compared with control (nonfunctioning alarm) or no treatment, at reducing the number of wet nights (mean deviation = −2.68 nights; 95% CI, −4.59 to −0.78), at achieving 14 consecutive dry nights (relative risk [RR] = 7.23; 95% CI, 1.40 to 37.33), and maintaining dryness after discontinuation of treatment (RR = 9.67; 95% CI, 4.74 to 19.76).27 They are typically offered in children older than six years and are most effective when family motivation is high.1,27 These include acoustic devices that produce a loud sound when moisture is detected by a sensor in the patient’s bed or underwear, training the child to respond to wetness in hopes of linking that sensation to bladder fullness.1,27 These alarms work best when enuresis is frequent and the family is well educated on how to respond to the device.1,15 Children may not respond to the alarm and may need to be awakened by parents or lifted from the bed (without waking) and taken to the bathroom to finish emptying their bladder.1,15 Follow-up is important two to three weeks after initiation. If no improvement is seen after six weeks, additional therapies should be offered. Discontinuation should be considered after 14 consecutive dry nights and can be restarted if relapse occurs.1 It is reasonable to revisit the use of an enuresis alarm every two years if not initially successful.1

Desmopressin, an analogue of vasopressin (Pitressin) that temporarily decreases nighttime urine production, is the only U.S. Food and Drug Administration–approved drug for enuresis.28,29 Adverse effects of orally administered desmopressin (e.g., water toxicity, hyponatremia) are rare. Intranasal desmopressin is no longer approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treatment of nocturnal enuresis secondary to high incidences of hyponatremia.29 Dosages for medications1 are shown in Table 6.15,28–33 Response rates are high compared with placebo (1.34 fewer wet nights a week; 95% CI, 1.11 to 1.57), and failure to achieve 14 consecutive dry nights is lower (RR = 0.84; 95% CI, 0.79 to 0.91).28 Desmopressin was noted to have a higher relapse rate compared with enuresis alarms (65% vs. 46%; RR = 1.42; 95% CI, 1.05 to 1.91).28

| Drug | Dosing | Serious reactions | Contraindications | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Desmopressin (tablet) Nasal formulation not recommended Melt tablets are available outside the United States | 0.2 to 0.6 mg, take 30 to 60 minutes before bedtime Start with 0.2 mg and increase by 0.2 mg every 14 days until effective dose reached (maximum dose: 0.6 mg nightly) | Hyponatremia, water toxicity (presenting as headache, nausea, vomiting, seizures), thrombus, anaphylaxis | Hypersensitivity to drug, known hypercoagulopathy, polyuria, polydipsia, renal impairment, electrolyte impairment Consider holding for acute illnesses | Safe medication, especially in its oral form To prevent serious adverse effects, fluid intake should be limited to 250 mL in the evening, with no fluid intake one hour before the medication is taken until at least eight hours after Response should be assessed every two weeks and continued at effective dosage; after three months tapering can be considered Often used as needed for special occasions (e.g., sleepovers, summer camp) |

| Imipramine (tablet) | Six to 12 years of age 10 to 50 mg nightly; start with 10 mg and increase by 10 mg every one to two weeks until effective dose reached (maximum dosage: 50 mg nightly) Older than 12 years 10 to 75 mg nightly; start with 10 mg and increase by 10 to 25 mg nightly every one to two weeks (maximum dosage: 75 mg nightly) | Cardiotoxicity, unstable arrhythmia (ventricular), mood (hallucinations/mania), and motor (extrapyramidal symptoms) changes | Hypersensitivity to drug/class, long QT syndrome, history of syncope or palpitations, family history of sudden cardiac arrest, caution in patients with existing seizure or movement disorder Caution in patients with existing mood disorders, including depression, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia | Screening electrocardiography for long QT syndrome recommended before starting Should be given one hour before bedtime; therapeutic response should be assessed one month after starting; can use in combination with desmopressin if not initially effective To prevent drug tolerance, consider one- to two-week drug holiday every third month of treatment When discontinuing, must taper (reduce dose by 50% every one to two weeks) to prevent withdrawal adverse effects |

| Oxybutynin (tablet) Immediate- and extended-release forms available | Immediate-release dosage for children five years and older Start at 2.5 mg nightly, can increase to 5 mg nightly after one week Extended-release form for children six years and older Start at 5 mg daily, increase by 5 mg weekly as needed (maximum dosage: 20 mg daily) | Allergic reactions (angioedema/anaphylaxis), hallucinations, psychosis, seizures, tachycardia | Hypersensitivity to drug/class, history of urinary retention or obstruction | Immediate-release form should be given one hour before bedtime Extended-release form should be given at the same time every day; consider extended-release form if daytime lower urinary tract symptoms are present Treatment effects may not be immediate and should be assessed one to two months after starting Can be used as monotherapy but is often used with desmopressin if it is not effective alone and with no adverse effects Consider gradually tapering every third successful treatment month If child develops dysuria while taking the medication, consider assessing for urinary retention If wet nights return after initial success while taking the medication, consider evaluating for and treating constipation |

Effectiveness may be improved by restricting desmopressin therapy to monosymptomatic enuresis, limiting fluid intake to 200 mL in the last hour before bedtime, and using only in children with nocturnal polyuria.1 Therapy should be discontinued if no improvement is seen after one to two weeks of treatment.1,15 If effective, treatment can be continued for years with periodic drug holidays to see whether natural resolution has occurred.1,15 Desmopressin may also be used only as needed during special occasions when it is important for the child to remain dry (e.g., sleepovers, summer camp).1,15 Combining desmopressin with enuresis alarm therapy, compared with desmopressin alone, leads to fewer wet nights (0.88 fewer wet nights per week; 95% CI, 0.38 to 1.38).27

What Treatment Strategies Should Be Offered When Enuresis Alarm Therapy and/or Desmopressin Is Not Successful?

When first-line therapies are not successful, the physician should evaluate for comorbidities, such as constipation, sleep disorders, or behavioral issues, and address these. Medications such as anticholinergics and tricyclic anti-depressants, especially in combination with first-line therapies, may be effective. Pediatric urology consultation should be considered in refractory cases. Figure 1 shows an algorithm for treating nocturnal enuresis in children.1,14–17,21–24,27–32

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

When first-line therapies fail to achieve dry nights, reevaluate and address secondary causes (e.g., constipation, behavioral issues, sleep-disordered breathing).1,15 Additional medications useful in treating monosymptomatic enuresis include imipramine and oxybutynin30,33 (Table 615,28–33). Imipramine has several effects benefiting enuresis, including antispasmodic and central nervous system effects.33 Imipramine may be used as monotherapy if desmopressin has been ineffective or in conjunction with oxybutynin.30,33 Compared with placebo, imipramine results in one fewer wet nights per week (mean deviation = −0.95; 95% CI, −1.40 to −0.50) and fewer children unable to achieve 14 consecutive dry nights (78% vs. 95%; RR = 0.74; 95% CI, 0.61 to 0.90).30 When imipramine plus oxybutynin is compared with placebo, fewer children are unable to achieve 14 consecutive dry nights while taking the placebo (33% vs. 78%; RR = 0.43; 95% CI, 0.23 to 0.78).30 Adverse effects of imipramine include dry mouth, mood changes, and cardiotoxicity. Electrocardiography to rule out long QT syndrome is prudent before starting.33

Oxybutynin as monotherapy is not recommended, but it may be used to treat monosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis in conjunction with desmopressin or imipramine.31,33 One retrospective study showed a 92.2% (P < .05) resolution of enuresis after six months of treatment compared with 79.5% (P < .05) with desmopressin alone.32 Relapse after cessation of treatment was not studied. Effectiveness is likely due to bladder antispasmodic properties and may provide benefit in nonmonosymptomatic enuresis cases with daytime lower urinary tract symptoms.33

Refractory cases should be referred to a pediatric urologist for further workup and consideration of alternate medication regimens, peripheral electrostimulation, or botulinum toxin injections into the detrusor muscle.1,15 Medications with possible effectiveness but high adverse-effect profiles include indomethacin, diazepam (Valium), mirabegron (Myrbetriq), and atomoxetine (Strattera).31 Hypnosis, psychotherapy, acupuncture, and chiropractic care have also been studied but only in small trials.34

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Baird, et al.35; Ramakrishnan36; Thiedke37; and Cendron.38

Data Sources: We searched Essential Evidence Plus, PubMed, and Google Scholar. Key words included enuresis, nocturnal enuresis, bedwetting, risk factor for enuresis, enuresis treatment, monosymptomatic enuresis, non-monosymptomatic enuresis, desmopressin, bed alarm, mirabegron, enuresis long-term outcomes, and enuresis clinical guidelines. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, and medical society guidelines. Recommendations were derived from International Children’s Continence Society’s guidelines and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence clinical guideline on bedwetting in under 19s. Search dates: December 2021 to August 2022.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the U.S. Air Force, or the U.S. government.