Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(5):557-564

Related Letter to the Editor: Compression Stockings May Reduce Postthrombotic Syndrome

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Edema is a common clinical sign that may indicate numerous pathologies. As a sequela of imbalanced capillary hemodynamics, edema is an accumulation of fluid in the interstitial compartment. The chronicity and laterality of the edema guide evaluation. Medications (e.g., antihypertensives, anti-inflammatory drugs, hormones) can contribute to edema. Evaluation should begin with obtaining a basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, thyroid function testing, brain natriuretic peptide levels, and a urine protein/creatinine ratio. Validated decision rules, such as the Wells and STOP-Bang (snoring, tired, observed, pressure, body mass index, age, neck size, gender) criteria, can guide decision-making regarding the possibility of venous thromboembolic disease and obstructive sleep apnea, respectively. Acute unilateral lower-extremity edema warrants immediate evaluation for deep venous thrombosis with a d-dimer test or compression ultrasonography. For patients with chronic bilateral lower-extremity edema, duplex ultrasonography with reflux can help diagnose chronic venous insufficiency. Patients with pulmonary edema or elevated brain natriuretic peptide levels should undergo echocardiography to assess for heart failure. Lymphedema is often a clinical diagnosis; lymphoscintigraphy can be performed if the diagnosis is unclear. Treatment of edema is specific to the etiology. Diuretics are effective but should be used only for systemic causes of edema. Ruscus extract and horse chestnut seed demonstrate moderate-quality evidence to improve edema from chronic venous insufficiency. Compression therapy is effective for most causes of edema.

Edema is a frequent manifestation of systemic illness resulting in maldistribution of total body water. Total body water is divided into intracellular (two-thirds) and extracellular (one-third) compartments. The extracellular compartment is further divided into plasma (one-fourth) and interstitial fluid (three-fourths). Edema is characterized by excess fluid accumulation in the interstitial compartment and occurs because of an imbalance of capillary hemodynamics as a result of one or more of the following mechanisms: increased oncotic pressure of the interstitial space, increased intravascular hydrostatic pressure, increased permeability of the endothelial barrier, decreased oncotic pressure within the capillary, or poor lymphatic drainage.1,2 Although edema is often localized to the extremities, fluid may also accumulate throughout the entire body (anasarca).2

Although limited data are available on the prevalence of lower-extremity edema, recent estimates indicate that approximately 20% of adults older than 50 years have edema.3 Peripheral edema is a common finding in primary care and can be diagnostically challenging. Edema may be a sign of unrecognized systemic disease and can result in functional impairment. Although often characterized as edema, lipedema is more correctly described as maldistribution of fat in the extremities.4 This article focuses on diagnosing and treating localized edema, particularly in the lower extremities.

History and Physical Examination

A detailed history can help narrow the differential diagnosis of edema. Time course and location of symptoms should be determined to help stratify patients based on chronic (more than three months) or acute/subacute (less than three months) edema, as well as unilateral or bilateral edema5 (Table 15–7). The presence of pain suggests deep venous thrombosis (DVT), chronic venous insufficiency (CVI), or complex regional pain syndrome. Patients with CVI report aching and heaviness of extremities.8 Edema that worsens with prolonged standing suggests an underlying venous etiology. The presence of dyspnea or orthopnea should prompt consideration for congestive heart failure (CHF), whereas heat intolerance, fatigue, and weight loss may suggest Graves disease.5–7

| Unilateral | Bilateral | |

|---|---|---|

| Acute | Deep venous thrombosis* Infection Insect or animal bite Ruptured Baker cyst Superficial venous thrombosis Trauma (e.g., ruptured muscle, compartment syndrome, fracture) | Acute congestive heart failure* Medications* Acute cirrhosis Acute renal failure Proximal deep venous thrombosis (e.g., inferior vena cava thrombosis) |

| Chronic | Chronic venous insufficiency* Complex regional pain syndrome Lymphedema Postthrombotic syndrome Proximal vein compression | Chronic congestive heart failure, cirrhosis, or nephrotic syndrome* Chronic venous insufficiency* Lymphedema* Medications* Pregnancy* Pulmonary hypertension* Lipedema Obstructive sleep apnea Thyroid disease |

Risk factors for DVT should be assessed, including a history of venous thromboembolism, active malignancy, immobilization, or recent surgery.9 Previous radiation or surgery to an extremity may disrupt lymphatic drainage, resulting in lymph-edema.4 A comprehensive review of the patient’s medication list is essential because medications may cause or contribute to edema (Table 2).5–7,10

| Medication class | Examples |

|---|---|

| Antihypertensives | Amlodipine (Norvasc), beta blockers, clonidine, diltiazem, hydralazine, minoxidil, nifedipine |

| Anti-inflammatory drugs | Corticosteroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| Chemotherapy | Cyclophosphamide, cyclosporine (Sandimmune), docetaxel (Taxotere), gemcitabine, targeted immunotherapy |

| Gabapentinoids | Gabapentin (Neurontin), pregabalin (Lyrica) |

| Hormones | Estrogen (Estratest), progesterone, testosterone |

| Thiazolidinediones | Pioglitazone (Actos) |

| Other | Acyclovir, antipsychotics, monoamine oxidase inhibitors |

On physical examination, nonpitting edema suggests pretibial myxedema or later stages of lymphedema, whereas pitting edema is associated with CVI, DVT, or early lymphedema. Pitting edema has been classically graded on a 1 to 4 scale based on depth and rebound time; however, this scale lacks reliability and reproducibility.11 Erythema and tenderness suggest DVT, superficial venous thrombosis, cellulitis, or stasis dermatitis. Lipedema is typically tender, whereas lymphedema often is not. Bilateral lower-extremity edema that spares the dorsum of the feet is highly suggestive of lipedema4 (Figure 1). Stemmer sign, the inability to pinch up a fold of skin of the dorsal second toe, is pathognomonic for advanced lymphedema.4 Skin changes such as stasis dermatitis, hyperpigmentation, medial ankle ulceration, or lipodermatosclerosis (inflammation of subcutaneous fat leading to hyperpigmentation and thickening) are seen in CVI8 (Figure 2). Prominent venous vessels such as telangiectasias, reticular veins, and varicose veins are also common in CVI.8 Hyperkeratosis or verrucous lesions are suggestive of lymphedema4 (Figure 312). Crescent-shaped ecchymosis of the ankle may suggest a ruptured Baker (popliteal) cyst or gastrocnemius muscle.7 The presence of an S3 heart sound (positive likelihood ratio [LR+] = 11.0), abdominojugular reflux (LR+ = 6.4), or jugular venous distention (LR+ = 5.1) increases the likelihood of CHF.13 Common findings for cirrhosis include ascites (LR+ = 7.2) and spider nevi (LR+ = 4.3).14

Diagnosis

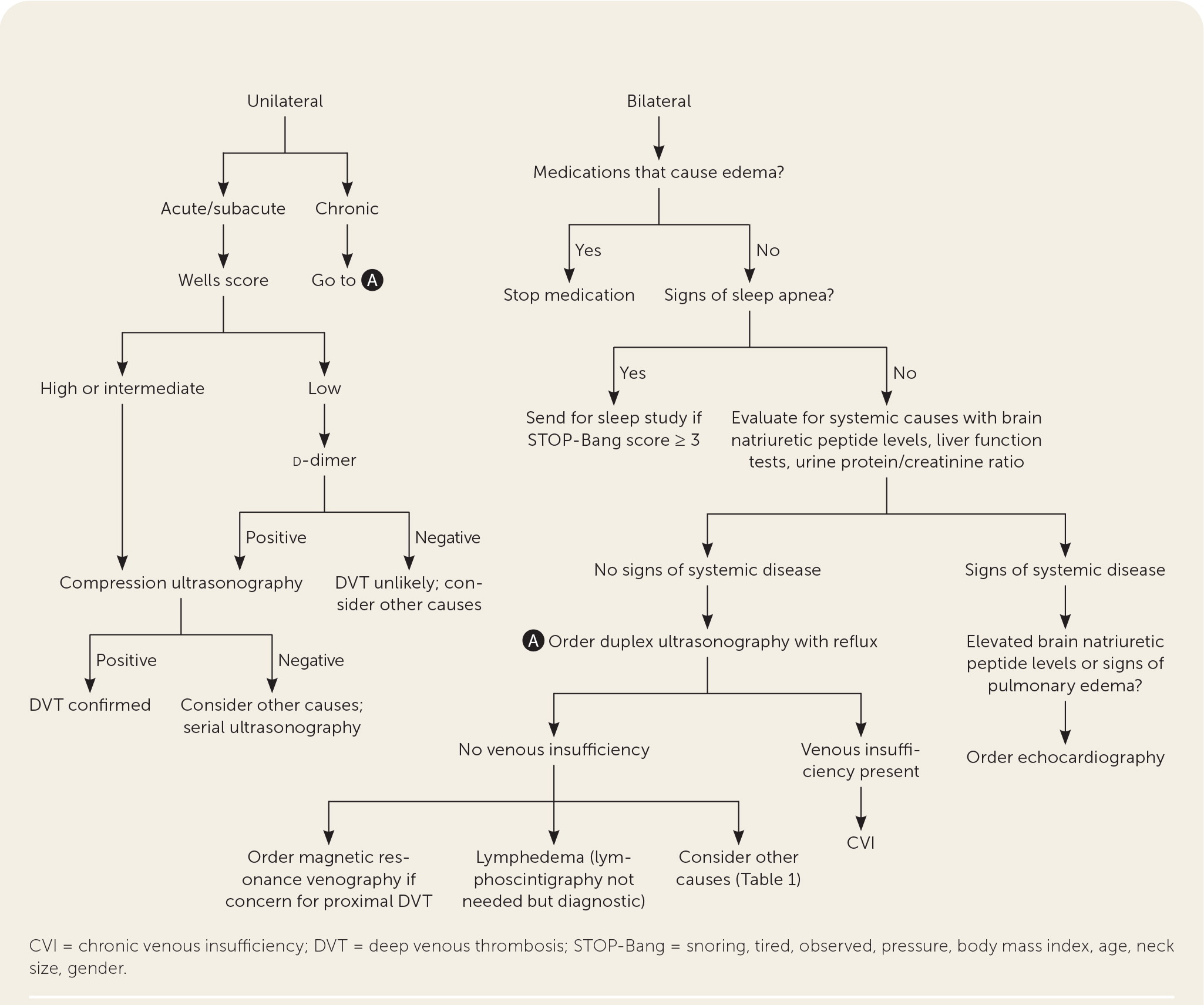

A practical diagnostic approach is to stratify edema based on duration and location to help narrow the differential diagnosis and ensure a cost-effective evaluation (Table 15–7 and Figure 4). Initial laboratory workup should include brain natriuretic peptide levels, thyroid-stimulating hormone, liver function tests, basic metabolic panel, and urine protein/creatinine ratio.5–7

ACUTE/SUBACUTE UNILATERAL EDEMA

Acute lower-extremity edema requires urgent evaluation because several potential causes require timely intervention. DVT, cellulitis, trauma, and hematoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis with acute lower-extremity edema. The Wells criteria should be used to determine the risk of DVT. The Wells score stratifies patients into low (5%), intermediate (17%), and high (17% to 53%) pretest probability for DVT (Table 3).15 A high Wells score (LR+ = 5.2) is more useful than any single clinical feature in diagnosing DVT.16,17 Patients with a low pretest probability of DVT should have d-dimer testing, whereas those with intermediate and high risk should immediately undergo compression ultrasonography18,19 (Figure 4). The d-dimer test is very highly sensitive (96%) but not very highly specific (35%),17 and patients with a positive d-dimer result should subsequently undergo compression ultrasonography. If DVT is ruled out, then alternative etiologies should be considered. If clinical suspicion remains high for DVT, serial ultrasonography should be performed to evaluate for DVT.17 May-Thurner syndrome should be considered in the setting of left lower-extremity edema and DVT. May-Thurner syndrome is an anatomic disorder in which the left common iliac vein is compressed by the right femoral artery, resulting in edema, venous hypertension, and increased risk of DVT.20 Magnetic resonance venography can be used to evaluate for May-Thurner syndrome.21 Recognizing DVT caused by May-Thurner syndrome is important because diagnosis requires advanced imaging, and management may require catheter-directed thrombolysis.20

| Signs or symptoms | Scoring |

|---|---|

| Active malignancy within the past 6 months | + 1 |

| Paralysis, paresis, or recent plaster immobilization of the lower extremities | + 1 |

| Recent immobility for > 3 days or major surgery in the past 12 weeks | + 1 |

| Calf swelling > 3 cm in comparison to contralateral leg | + 1 |

| Collateral superficial veins present (nonvaricose) | + 1 |

| Entire lower-extremity edema | + 1 |

| Localized tenderness along deep venous system | + 1 |

| Pitting edema that is confined to the symptomatic lower extremity | + 1 |

| History of DVT | + 1 |

| Alternative diagnosis at least as likely as DVT | − 2 |

| Score interpretation (prevalence of DVT) | |

| 0: low risk (5%) | |

| 1 to 2: intermediate risk (17%) | |

| ≥ 3: high risk (17% to 53%) |

ACUTE/SUBACUTE BILATERAL EDEMA

Acute bilateral lower-extremity edema may be due to decompensated CHF, nephrotic syndrome, medications, or proximal venous obstruction. Echocardiography should be performed in patients with elevated brain natriuretic peptide levels or signs of pulmonary edema (e.g., orthopnea, dyspnea on exertion) to assess for heart failure. Medications can result in edema shortly after initiation, and a detailed medication review should be performed10 (Table 25–7,10).

CHRONIC EDEMA

Chronic unilateral lower-extremity edema is less common but can be seen in CVI, complex regional pain syndrome, postthrombotic syndrome, and lymphedema. Causes of chronic bilateral lower-extremity edema include CVI, lymphedema, obstructive sleep apnea, pregnancy, chronic CHF, chronic nephrotic syndrome, cirrhosis, medications, and lipedema. Lower-extremity edema commonly occurs in patients with obstructive sleep apnea22,23; use of the validated STOP-Bang (snoring, tired, observed, pressure, body mass index, age, neck size, gender) questionnaire should be considered to screen for obstructive sleep apnea.24

If systemic causes (i.e., CHF, nephrotic syndrome, obstructive sleep apnea, medications) are ruled out or less likely, evaluation should focus on lymphedema and CVI. Examination findings can help differentiate CVI from lymphedema. Duplex ultrasonography with reflux can diagnose CVI by demonstrating venous insufficiency or obstruction.25 If the diagnosis of lymphedema is unclear, lymphoscintigraphy may be warranted.5,26,27 Although lymphoscintigraphy is the test of choice for lymphedema, it may be impractical because it is invasive, time intensive, painful, and often unavailable outside tertiary centers.26,27

Management

The management of edema depends on the etiology, but several general principles apply in managing all causes of edema. Discontinuing or switching medications that result in edema may improve swelling (Table 25–7,10). For patients taking calcium channel blockers, adding an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor may reduce peripheral edema.28 Compression therapy is helpful for most causes of lower-extremity edema. Before initiating compression therapy, an ankle-brachial index should be performed in patients at risk of peripheral artery disease because compression stockings are contraindicated in such patients.8 No evidence supports the use of diuretics in treating nonsystemic causes of edema.

CHRONIC VENOUS INSUFFICIENCY

CVI treatment aims to promote venous return to the heart. First-line therapy for CVI is compression therapy, often achieved using graduated compression stockings.8 Other options for compression therapy include elastic bandages, adjustable compression garments, and intermittent pneumatic compression.8 Graduated compression stockings exert higher pressures at the ankle and progressively lower pressures at the calf.8 Graduated compression stockings with a 20 to 40 mm Hg pressure have been shown to reduce edema, pain, and ulceration caused by CVI.8,29 Elastic bandages and adjustable compression garments are alternatives for patients who cannot tolerate compression stockings.8

In addition to compression therapy, weight loss, physical therapy, and phlebotonics may improve CVI. Weight loss from bariatric surgery reduces edema and ulcers associated with CVI.30 Phlebotonics are a group of agents that promote venous return. A Cochrane review concluded with moderate certainty that horse chestnut seed can slightly reduce edema from CVI and is generally safe.31 Ruscus extract has also been shown to reduce edema and pain in patients with CVI.8,32 A Cochrane review demonstrated that pentoxifylline effectively treats venous ulcers.33 Patients with persistent symptoms should be referred to a vascular specialist to discuss invasive therapies (e.g., sclerotherapy, venous ablation procedure).34

LYMPHEDEMA

Treatment of lymphedema is challenging, often requiring a multifaceted approach with combined decongestive therapy (i.e., compression therapy, manual lymphatic drainage, exercise, and skin care).26 Compression therapy is initially accomplished using inelastic compression bandages because they more rapidly improve edema compared with elastic compression stockings.26,35 After edema improves, patients can transition to compression stockings (40 mm Hg or greater).26 A prospective trial of patients using intermittent pneumatic compression showed improved edema and functional status; however, there are no recent large randomized controlled trials on the use of intermittent pneumatic compression.36

Manual lymphatic drainage is a technique where specialized therapists massage the lower extremity to promote lymphatic flow. A 2015 Cochrane review demonstrated that adding manual lymphatic drainage to compression bandages reduces swelling.37 Manual lymphatic drainage should be started simultaneously with initial compression therapy. Exercise should be encouraged in patients with lymphedema because it promotes lymphatic flow by activating surrounding muscles.26 Patients with lymphedema are prone to skin infections, and they should monitor their skin and use moisturizers. Patients with persistent or progressive symptoms should be referred to a lymphatic surgeon to evaluate for tissue debulking or lymphovenous bypass surgery. A recent systematic review found that lymphovenous bypass reduces limb circumference by 1.9 to 2.4 cm.38

DEEP VENOUS THROMBOSIS

For most patients with a new DVT, oral factor Xa inhibitors can be used as first-line agents and should be continued for at least three months.39 Patients with recurrent or unprovoked venous thromboembolism may require a longer duration of anticoagulation, depending on their bleeding risk.39,40 Postthrombotic syndrome develops in 25% to 50% of patients after DVT and is characterized by edema, pain, and skin changes.41 A 2017 Cochrane review showed that compression stockings prevent the development of post-thrombotic syndrome (relative risk = 0.62).42 A different Cochrane review concluded with low certainty that patients with known postthrombotic syndrome may have improved edema with the use of compression stockings.43

SYSTEMIC DISEASE

Patients with CHF, cirrhosis, and nephrotic syndrome require a multifaceted treatment approach, which includes the use of diuretics. In patients with diuretic-resistant CHF, torsemide (Demadex) should be considered over furosemide (Lasix). A recent meta-analysis of patients with CHF compared the two medications, demonstrating that torsemide reduced the risk of hospitalization (number needed to treat = 23), improved New York Heart Association functional status (number needed to treat = 5), and lowered cardiac mortality (number needed to treat = 40).44 Patients with ascites from cirrhosis should be started on a 5:2 ratio of spironolactone and furosemide.45

LIPEDEMA

Lipedema is a rare condition, and no high-quality evidence exists for its treatment. A small, randomized controlled trial with 30 participants showed that combined decongestive therapy may improve pain and reduce limb volume.46

PREGNANCY

Edema associated with pregnancy can be treated with conservative measures. Patients should be advised to reduce time on their feet, elevate their legs, lie on their left side (relieves uterine pressure from the inferior vena cava), and wear compression stockings.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Trayes, et al.12; and O’Brien, et al.47

Data Sources: A PubMed search was performed for meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, and clinical reviews. Key search terms were edema, peripheral edema, lower-extremity edema, medication-associated edema, pitting edema, chronic venous insufficiency, lymphedema, lipedema, lipodermatosclerosis, and obstructive sleep apnea. Also reviewed were the Cochrane database, JAMA Evidence, ACCESSSS Smart Search, Essential Evidence Plus, and UpToDate. Search dates: January and October 2022.