Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(6):695-700

Patient information: See related handout on galactorrhea (milk discharge), written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Galactorrhea is the production of breast milk that is not the result of physiologic lactation. Milky nipple discharge within one year of pregnancy and the cessation of breastfeeding is usually physiologic. Galactorrhea is more often the result of hyperprolactinemia caused by medication use or pituitary microadenomas, and less often hypothyroidism, chronic renal failure, cirrhosis, pituitary macroadenomas, hypothalamic lesions, or unidentifiable causes. A pregnancy test should be obtained for premenopausal women who present with galactorrhea. In addition to prolactin and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels, renal function should also be assessed. Medications contributing to hyperprolactinemia should be discontinued if possible. Treatment of galactorrhea is not needed if prolactin and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels are normal and the discharge is not troublesome to the patient. Magnetic resonance imaging of the pituitary gland should be performed if the cause of hyperprolactinemia is unclear after a medication review and laboratory evaluation. Cabergoline is the preferred medication for treatment of hyperprolactinemia. Transsphenoidal surgery may be necessary if prolactin levels do not improve and symptoms persist despite high doses of cabergoline and in patients who cannot tolerate dopamine agonist therapy.

Galactorrhea is the production of breast milk that is not the result of physiologic lactation. The typical milky nipple discharge associated with galactorrhea can result from a variety of causes, including physical stimulation, endocrinopathies, and pituitary disorders. The decision to treat galactorrhea depends on the underlying cause and whether the discharge is troublesome to the patient.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Dopamine agonists are first-line therapy for hyperprolactinemia.13,28 Cabergoline is preferred because it has been shown to more effectively lower prolactin levels and decrease tumor size.29 | A | Consistent, good-quality patient-oriented evidence; one randomized controlled trial; one prospective cohort study |

| Dopamine agonist therapy should be continued for at least two years, after which tapered discontinuation may be attempted if prolactin levels have normalized and tumor size is significantly reduced.32–34 | C | Expert opinion |

| Treatment of galactorrhea is not necessary if trophic hormone levels are normal and the patient has minimal symptoms.13,28 | C | Expert opinion, consensus guideline |

Epidemiology

Discharge from galactorrhea presents one year or more after pregnancy and the cessation of breastfeeding.1

Galactorrhea can occur in postmenopausal women and in men.2

The prevalence of galactorrhea is unknown, but the condition is estimated to occur in about 20% to 25% of women.3

Nipple discharge is the third most common breast-related medical issue after masses and pain.4

Hyperprolactinemia may cause galactorrhea and is more common in women than men. The prevalence of hyperprolactinemia in women varies (0.4% of an unselected population, 5% of patients from a family planning clinic, 9% of women being evaluated for amenorrhea, and 17% of women with polycystic ovary syndrome).5,6

Diagnosis

Galactorrhea is milk production not related to pregnancy or breastfeeding within the past year or a breast abnormality.7

The differential diagnosis of galactorrhea and hyperprolactinemia includes physiologic causes, pharmacologic adverse effects, pituitary and hypothalamic conditions (e.g., prolactinoma), and systemic disease (Table 1).3,5,8–26

Antipsychotics and antidepressants are the medications most commonly associated with galactorrhea. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors account for 95% of cases.18,19

Prolactinomas are classified as microadenomas (less than 1 cm in diameter) or macroadenomas (1 cm or greater in diameter), with a symptomatic prevalence of 40 per 100,000 people and 10 per 100,000 people, respectively.11,21

Microadenomas are more common in premenopausal women, whereas macroadenomas are more common in men and older women.21

Prolactinomas are more common in women 20 to 50 years of age compared with men, at a ratio of 10:1. After 50 years of age, women and men are equally affected.22

| Physiologic |

| Pregnancy |

| Breastfeeding within the past year |

| Breast/nipple stimulation |

| Sexual activity |

| Exercise |

| Chest trauma (e.g., from herpes zoster, nipple rings, burns, or breast surgery) or lesions |

| Seizure (within one to two hours) |

| Pharmacologic |

| Antipsychotics |

| First-generation: phenothiazines, haloperidol |

| Second-generation: amisulpride, risperidone (Risperdal), olanzapine (Zyprexa), quetiapine |

| Antidepressants |

| Serotonergic: paroxetine, fluoxetine, sertraline, fluvoxamine, escitalopram |

| Tricyclic: clomipramine |

| Monoamine oxidase inhibitors: clorgiline, pargyline (not available in the United States) |

| Antihypertensives: verapamil, methyldopa, reserpine |

| Narcotics: opioids, cocaine |

| Antiemetics: metoclopramide, domperidone |

| Protease inhibitors: ritonavir, saquinavir |

| Pathologic |

| Pituitary: prolactinoma, acromegaly, Cushing disease, compressive effect (non–prolactin-secreting macroadenoma, Rathke cyst) |

| Hypothalamic |

| Tumors: craniopharyngiomas, meningioma, germinoma, gliomas, metastatic disease |

| Infiltrative diseases: sarcoidosis, Langerhans cell histiocytosis, tuberculosis |

| Neuroaxis irradiation |

| Systemic diseases: primary hypothyroidism, chronic renal failure, cirrhosis, adrenal insufficiency |

SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS

Galactorrhea typically presents as bilateral, nonbloody, milk white nipple discharge involving multiple ducts.7 The discharge may be clear or greenish.

Symptoms of galactorrhea are a result of hyperprolactinemia and may include changes in menstruation (amenorrhea, hypo- or hypermenorrhea, irregular cycles, oligomenorrhea), decreased libido, infertility, erectile dysfunction, or gynecomastia.10,16

Pituitary or hypothalamic lesions may present as headaches or vision changes due to compression of the optic chiasm and surrounding structures.24

Galactorrhea may also be associated with signs and symptoms of underlying hypothyroidism, chronic renal failure, or cirrhosis.5

DIAGNOSTIC TESTING

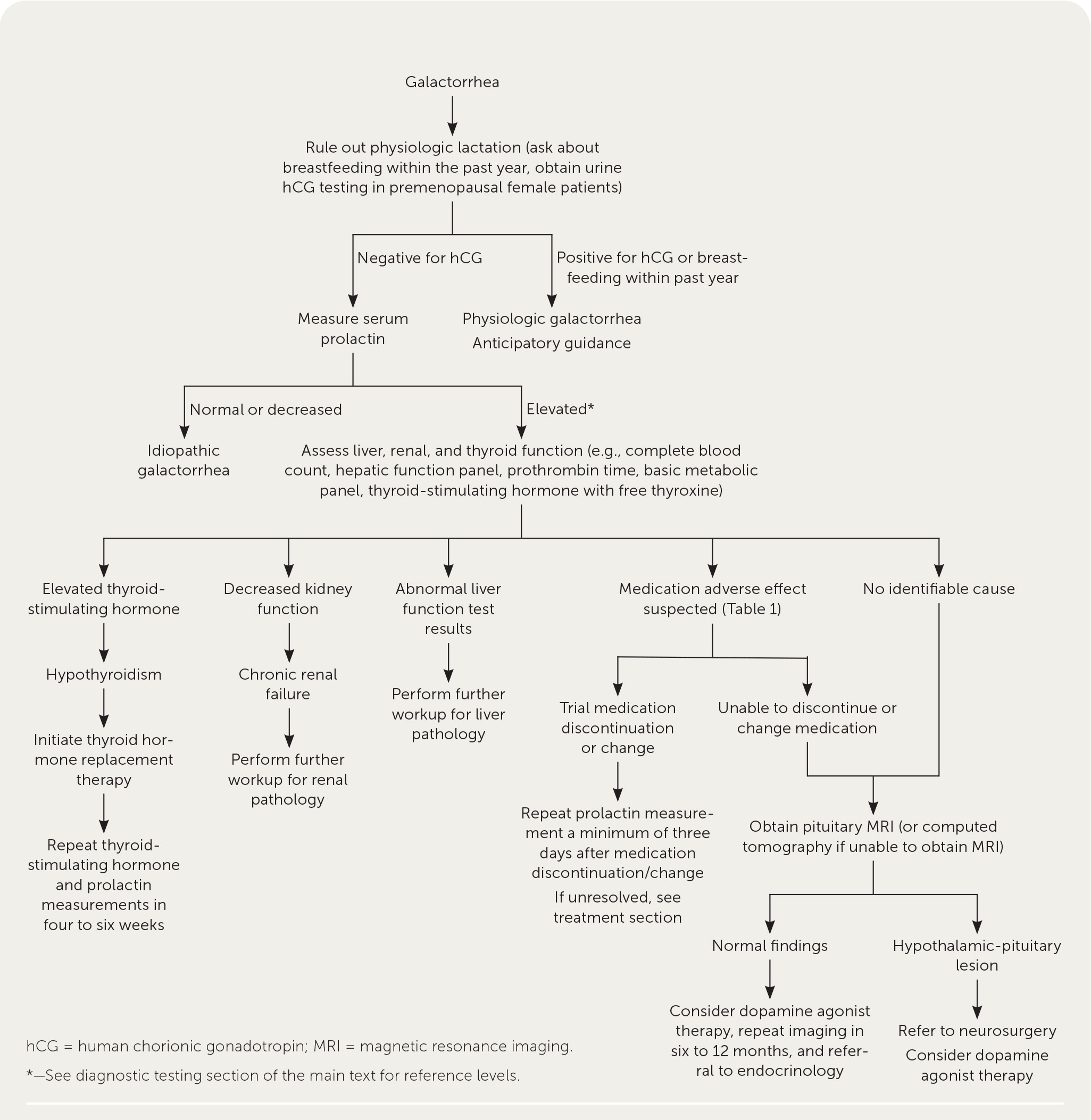

A suggested approach to the evaluation of galactorrhea is summarized in Figure 1.5,11–14

The first step in the evaluation of premenopausal women is to rule out physiologic lactation by asking about breastfeeding and pregnancy within the past year and obtaining a urine pregnancy test. During a normal pregnancy, serum prolactin rises to 200 to 500 ng per mL (200 to 500 mcg per L).5

All patients should receive an ophthalmologic examination, including visual acuity, pupil, fundus, and ocular motor assessment, evaluation for ptosis, and visual field assessment to check for compression of the optic chiasm by pituitary or hypothalamic lesions.25

If galactorrhea is confirmed, serum prolactin measurement and medication history should be completed.17

Because exercise and nipple stimulation can elevate serum prolactin levels, they should be avoided for at least 30 minutes before the measurement.17

According to one laboratory, prolactin levels are elevated if greater than 30 ng per mL (30 mcg per L) in nonpregnant premenopausal females, greater than 20 ng per mL (20 mcg per L) in postmenopausal women, and greater than 18 ng per mL (18 mcg per L) in males.26 These values may differ depending on the laboratory.

The degree of prolactin elevation can indicate possible etiologies, although there can be exceptions. A prolactin level less than 100 ng per mL (100 mcg per L) is associated with drug-induced hyperprolactinemia, systemic disease, or microadenoma, whereas a prolactin level greater than 250 ng per mL (250 mcg per L) is highly suggestive of a macroadenoma.17

If prolactin is elevated, further testing should be performed to rule out systemic etiologies, including thyroid-stimulating hormone with free thyroxine for primary hypothyroidism; liver function testing (complete blood count, hepatic function panel, and prothrombin time) for cirrhosis; and basic metabolic panel for chronic renal failure.5,16

If the cause of hyperprolactinemia is unclear after laboratory evaluation and review of medications, pituitary imaging is recommended to assess for pituitary and hypothalamic lesions.15,16

Pituitary imaging should include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain with and without contrast (contrast-enhanced MRI has 90% sensitivity), or computed tomography of the brain with contrast if MRI is unavailable.22,27

Treatment

PROLACTINOMA

The goal of treatment is to resolve hypogonadal symptoms and reduce tumor size if symptoms are causing significant morbidity (e.g., headache, impotence, infertility, osteoporosis, visual field defects). Galactorrhea itself usually is not an indication for treatment.13,28

Dopamine agonists (e.g., cabergoline and bromocriptine [Parlodel]) are first-line therapy for hyperprolactinemia caused by a prolactinoma.13,28

Cabergoline more effectively lowers prolactin levels and decreases tumor size than bromocriptine.29 In an open-label trial, tumors were reduced at 24 months in 82% of patients with macroadenomas and 90% of patients with microadenomas who used cabergoline, compared with 46% and 57% of patients, respectively, who used bromocriptine.29

The usual dosage of cabergoline is 0.25 to 2 mg orally once per week or in a divided dose twice per week. Common adverse effects include nausea, dizziness, and headache. Cabergoline may exacerbate psychosis or decrease the effectiveness of antipsychotics.30

The usual dosage of bromocriptine is 2.5 to 15 mg orally once per day or in a divided dose twice per day. The adverse effects are similar to cabergoline.31

The dose of cabergoline or bromocriptine is gradually increased until the prolactin level normalizes.13

Surveillance during treatment should include prolactin measurements every three months and a repeat MRI after one year (or earlier if prolactin levels continue to rise or new symptoms develop).13

Regular visual field examinations are indicated for macroadenomas that possibly involve the optic chiasm.13

Because concurrent abnormalities in thyroid-stimulating hormone and luteinizing hormone or follicle-stimulating hormone are common, monitoring for these abnormalities is an essential part of treatment.13

Dopamine agonist therapy should continue for at least two years, after which tapered discontinuation may be attempted if prolactin levels have normalized and tumor size is significantly reduced.32–34

The risk of hyperprolactinemia recurrence after at least two years of treatment with a dopamine agonist is as high as 66%. A higher risk of recurrence is associated with larger tumor size and shorter treatment duration.34

Follow-up after treatment should include prolactin measurement every three months for the first year and annually thereafter. MRI should be repeated if prolactin levels increase.13

Transsphenoidal surgery is indicated if prolactin levels do not improve and symptoms persist despite high doses of cabergoline and in patients who cannot tolerate dopamine agonist therapy.13 Five years after surgery, 76% of patients are disease-free.35

Potential complications of transsphenoidal surgery include hypopituitarism, diabetes insipidus, cerebrospinal fluid leak, and local infection.36

PREGNANCY

Dopamine agonist therapy should be discontinued if a patient becomes pregnant.13

If dopamine agonist therapy must be used during pregnancy, bromocriptine is preferred.37

The risk of significant tumor growth during pregnancy is very low (less than 3%) in patients with microadenomas.38

Because the pituitary gland transiently increases in volume during pregnancy, it may be reasonable to continue dopamine agonist therapy if a macroadenoma is impinging on the optic chiasm.13,39

The risk of symptomatic pituitary enlargement during pregnancy in patients who have not undergone prior debulking surgery is 31%.28 These patients should be referred to an endocrinologist experienced in the management of pituitary tumors.

IDIOPATHIC HYPERPROLACTINEMIA

Treatment indications and methods for idiopathic hyperprolactinemia are the same as for prolactinoma-related hyperprolactinemia (i.e., dopamine agonists).34

MEDICATION-INDUCED HYPERPROLACTINEMIA

Symptomatic medication-induced hyperprolactinemia is managed by discontinuing the causative medication if possible.

If it is unclear whether a medication is causing hyperprolactinemia, the medication should be paused or transitioned to a new medication for at least three days prior to remeasurement of prolactin.13

If the suspected medication cannot be discontinued, an MRI is necessary to rule out a prolactin-secreting tumor before attributing hyperprolactinemia to use of the medication.13

If an MRI does not reveal a cause for hyperprolactinemia and the suspected medication is an antipsychotic that cannot be stopped or substituted, there are mixed recommendations on the use of dopamine agonists to treat these patients. Although prolactin level may improve, the addition of a dopamine agonist may worsen psychosis control.13

Because aripiprazole works as both a dopamine agonist and antagonist, it may be better tolerated than antipsychotics and is a possible treatment adjunct.40

CONSERVATIVE MANAGEMENT

Treatment of galactorrhea is not necessary if trophic hormone levels are normal and the patient has minimal symptoms.13,28

Nipple stimulation may perpetuate galactorrhea. Over-evaluation should be avoided in such circumstances.

Nursing pads can be used to manage moisture from nipple discharge. Although most pads are best suited for use with bras, some brands have an adhesive backing that can be placed directly onto clothing.

Patients with microadenomas, amenorrhea, and nonbothersome galactorrhea may choose treatment with combined low-dose oral contraceptives (and annual surveillance of prolactin level) or a dopamine agonist. Oral contraceptives are less costly and have a more favorable side effect profile.13

Premenopausal patients with hyperprolactinemia, normal menstrual cycles, and manageable galactorrhea do not require treatment. These patients should have periodic clinical reassessment and prolactin measurements. An MRI should be obtained if there is clinical evidence of a mass or if prolactin levels steadily increase.22 A similar approach can be used with postmenopausal patients with a microadenoma and manageable galactorrhea.22

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Huang and Molitch,1 Leung and Pacaud,41 and Peña and Rosenfeld.42

Data Sources: Essential Evidence Plus, the Cochrane database, and the PubMed Clinical Queries database were searched using the terms galactorrhea and nipple discharge. Additional PubMed searches and secondary research tools such as DynaMed, UpToDate, and Google Scholar were also reviewed. Search date: February 2022.