Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(2):152-158

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Skin conditions during pregnancy fall into three categories: benign hormone-related changes, preexisting skin conditions, and pregnancy-specific disorders. Benign hormonal skin changes (e.g., hyperpigmentation, striae gravidarum, hair and nail changes, vascular changes) are common during pregnancy and often improve or resolve postpartum. Topical therapies, including tretinoin, hydroquinone, and corticosteroids, can be helpful in the postpartum treatment of melasma. The severity of preexisting skin conditions such as acne vulgaris, condylomata acuminata, herpes simplex, hidradenitis suppurativa, and psoriasis varies during pregnancy. Treatment options for chronic skin conditions during pregnancy often differ from usual practice because of safety concerns. Discussion of potential risks and benefits is important. Low- to midpotency topical corticosteroids are generally considered safe during pregnancy, whereas extensive use of high-potency corticosteroids may be associated with low birth weight. Pregnancy-specific skin conditions include atopic eruption of pregnancy, polymorphic eruption of pregnancy, pemphigoid gestationis, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, and pustular psoriasis of pregnancy. Conditions that may cause adverse fetal outcomes and require consideration of antenatal fetal surveillance include intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, pemphigoid gestationis, and pustular psoriasis of pregnancy.

Skin conditions during pregnancy fall into three categories: benign hormone-related changes, preexisting skin conditions, and pregnancy-specific disorders. Classification of these conditions has evolved over time and varies in the literature. This article summarizes the most common terminology and groupings of these conditions.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| The most effective treatment for melasma is a combination of topical tretinoin, hydroquinone, and a corticosteroid.4 | B | Cochrane review of low-quality studies |

| In patients with a history of genital herpes simplex, suppressive antiviral therapy should be started at 36 weeks of gestation.9 | C | ACOG clinical guideline |

| Low- to midpotency topical corticosteroids are not associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes.23 | B | Cochrane review of low-quality studies |

| Intrahepatic cholestasis is an indication for fetal monitoring at the time of diagnosis, with delivery at 36 to 37 weeks of gestation.31,32 | C | ACOG clinical guidelines with expert opinion |

Hormonal Skin Changes in Pregnancy

Benign changes to the skin, hair, and nails often occur during pregnancy due to hormone fluctuations and changes in body composition.

HYPERPIGMENTATION

Hyperpigmentation is the most common skin change during pregnancy and is caused by increased levels of progesterone, estrogen, and melanocyte-stimulating hormone.1,2 Darkening of the skin around the nipples, areolae, and genital region can occur as early as the first trimester. Scars, nevi, and freckles on the breasts and abdomen may enlarge as the pregnancy progresses.2 Any changes to nevi that are concerning for malignancy should be biopsied during pregnancy.3

Generalized hyperpigmentation may develop in pregnant patients with lighter skin tones.1 Linea nigra (Figure 1), a vertical, hyperpigmented line on the abdomen, can develop in the second trimester. Patients should be reassured that this is a benign, self-limited change that resolves within a few months of delivery.1

Melasma (Figure 2), or mask of pregnancy, is an irregular darkening of the central face that occurs in up to 75% of patients.2 Because it can worsen with sun exposure, patients should use broad-spectrum sunscreen and avoid prolonged periods in the sun. Melasma resolves postpartum in 90% of cases but can recur with future pregnancies and use of oral contraceptives. Postpartum treatment options include topical tretinoin, hydroquinone, and corticosteroids.2 A 2010 Cochrane review showed that products containing all three drugs are most effective.4

STRIAE GRAVIDARUM

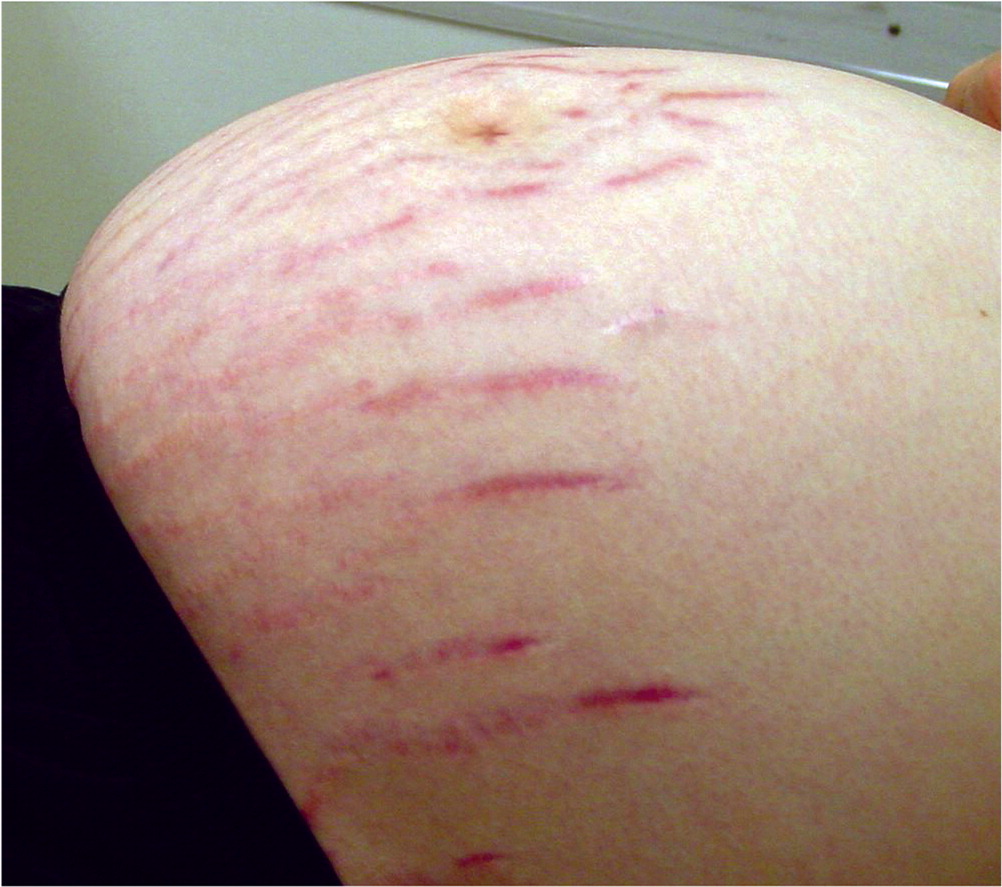

Striae gravidarum (Figure 35), also known as striae distensae or stretch marks, occur in 55% to 90% of pregnancies.6 These red or purple marks appear on the abdomen (most common), breasts, buttocks, and extremities.5 Underlying causes include mechanical stretching, genetic factors, and hormonal changes (e.g., estrogen, relaxin).6

Striae gravidarum are more common in women with younger age, higher prepregnancy body mass index, excessive weight gain during pregnancy, or a family history of the condition and in those who have newborns with a higher birth weight.6 They usually develop in the third trimester of singleton pregnancies and can be self-limited, fading postpartum.6 Over-the-counter topical treatments to prevent or reduce stretch marks have limited evidence of effectiveness. Common treatments include cocoa butter, vitamin E, olive oil, almond oil, and aloe vera.5,6 Topical products containing Centella asiatica or hyaluronic acid combined with daily massage may offer a modest preventive benefit.6 Postpartum treatment options include topical tretinoin, laser therapy, microdermabrasion, radiofrequency, and microneedling.6

HAIR AND NAIL CHANGES

Most pregnant people experience a thickening of scalp hair due to an increased anagen phase, and some develop mild to moderate hirsutism on the face, limbs, and back.1,2 Most pregnant people experience some degree of telogen effluvium postpartum that lasts up to 12 to 18 months. Rare changes such as male pattern baldness and hypertrichosis can occur in the antepartum or postpartum period due to increases in androgenic hormones.1

Nails tend to grow more quickly during pregnancy and may become more brittle; however, this resolves after delivery. Some pregnant patients are more susceptible to onychomycosis; patients should be encouraged to maintain good nail hygiene.1

VASCULAR CHANGES

Vascular changes related to increased estrogen levels include dilation, proliferation, and congestion of blood vessels, particularly small vessels. Spider angiomas (i.e., red, raised lesions located on the face, neck, arms, and chest) develop in up to 67% of pregnant people, with 75% of cases resolving postpartum.1,2 Palmar erythema occurs in up to 67% of pregnant people and is more common in those with lighter skin tones.2 Varicosities may be present in 40% of pregnant patients, and the condition may not resolve postpartum.2

Findings on the pelvic examination include vaginal erythema (Chadwick sign) and a purplish/bluish discoloration of the cervix caused by congestion of the pelvic vessels (Goodell sign).5 Edema or hyperemia of the gingiva, especially later in pregnancy, can lead to worsening gingivitis, and all pregnant patients should receive regular dental care.2

Preexisting Skin Conditions

| Condition | Effects | Selected treatments in pregnancy |

|---|---|---|

| Acne vulgaris 7 | Worsens, especially in the second and third trimesters | Topical therapies: benzoyl peroxide, azelaic acid, antibiotics (erythromycin 2%, clindamycin 1%) Severe cases: oral antibiotics (e.g., erythromycin) or oral corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone at < 20 mg per day for ≤ 1 month) and procedural interventions (e.g., pulsed light therapy) |

| Condylomata acuminata8 | Enlargement of lesions | Cryotherapy, laser therapy Extensive or refractory cases: imiquimod, surgical excision |

| Herpes simplex9 | Of those with a history of recurrent genital herpes simplex, 75% have an outbreak during pregnancy | Suppressive antiviral therapy with acyclovir or valacyclovir at 36 weeks of gestation Cesarean delivery if there are active genital lesions or prodromal symptoms at time of labor |

| Hidradenitis suppurativa 10,11 | Improves in pregnancy: 24% Worsens in pregnancy: 20% Worsens postpartum: 60% | Topical benzoyl peroxide, clindamycin 1% solution, oral antibiotics (e.g., cephalexin, amoxicillin/clavulanate, clindamycin, metronidazole [Flagyl], rifampin) Severe cases: intralesional corticosteroids (e.g., triamcinolone), laser-based treatment, surgical excision, TNF inhibitors |

| Pityriasis rosea 12–14 | More common in pregnancy Higher miscarriage rate with onset earlier in pregnancy | Supportive care |

| Psoriasis 15–17 | Usually improves in pregnancy and worsens postpartum | Emollients and low- to midpotency topical corticosteroids followed by ultraviolet B phototherapy Severe cases: TNF inhibitors, cyclosporine, systemic corticosteroids |

ACNE VULGARIS

Acne is the most common condition that may be affected by pregnancy. Increased androgen levels can worsen acne, especially in the second and third trimesters.

Topical therapies (e.g., benzoyl peroxide, azelaic acid, antibiotics) are preferred and considered safe for the treatment of mild to moderate acne during pregnancy. For more severe disease, a short course of oral antibiotics (e.g., erythromycin) or corticosteroids (e.g., prednisone) and procedural interventions (e.g., pulsed light therapy) are likely safe.7

CONDYLOMATA ACUMINATA

Condylomata acuminata (genital warts), usually caused by human papillomavirus 6 or 11, may enlarge during pregnancy. Cryotherapy is the first-line treatment during pregnancy, with laser therapy as a second-line option. Imiquimod or surgical excision may be considered for extensive or refractory cases. Podophyllotoxin derivatives are generally thought to be unsafe during pregnancy.8 The presence of genital condylomata does not preclude a vaginal birth unless there are large lesions that could obstruct the pelvic outlet or present unacceptable bleeding risk.18

HERPES SIMPLEX

Herpes simplex is a common infection that causes herpes labialis, gingivostomatitis, keratoconjunctivitis, and genital disease. Among patients with a history of recurrent genital herpes simplex, 75% will experience at least one recurrence during pregnancy. The highest risk of vertical transmission is when the patient's first infection occurs in the third trimester.

Pregnant patients with a history of genital herpes should be offered suppressive antiviral therapy (i.e., acyclovir or valacyclovir) starting at 36 weeks of gestation and continuing through delivery. Cesarean delivery is recommended if there are active genital lesions or prodromal symptoms at the time of labor.9

HIDRADENITIS SUPPURATIVA

Hidradenitis suppurativa is an immune-mediated skin condition involving inflammatory nodules, abscesses, and cysts that are complicated by fistulous tracts.19 A 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis showed that 24% of women with this condition improved during pregnancy, whereas 20% worsened; 60% experienced a postpartum flare-up.10 Topical benzoyl peroxide, clindamycin, and oral antibiotics such as cephalexin or amoxicillin/clavulanate are considered safe for the treatment of mild disease in pregnancy. Intralesional corticosteroids, laser-based treatment, surgical excision, and tumor necrosis factor inhibitors may be options for more severe disease.11

PITYRIASIS ROSEA

Pityriasis rosea is an acute, self-limited condition appearing as an erythematous, scaly rash over the trunk and limbs that may be related to reactivation of human herpesvirus 6 or 7. It occurs three times more often during pregnancy than nonpregnancy (18% vs. 6%).12 Symptoms last an average of 45 days during pregnancy, and treatment is supportive.12

Previous case series have reported a higher rate of miscarriage (62%) when pityriasis rosea develops in the first 15 weeks of gestation.13,14 However, a more recent pooled case series suggests that miscarriage, preterm birth, and low birth weight may be less common outcomes than previously thought.20 Additional risk factors for adverse outcomes include increased human herpesvirus 6 levels assessed by polymerase chain reaction, presence of enanthema, systemic symptoms, and involvement of more than 50% of the body.21,22

PSORIASIS

Psoriasis is a chronic, immune-mediated condition manifesting as scaly plaques, mostly on the scalp and extensor surfaces.19 Pregnancy's effect on disease severity is variable, with most patients improving during pregnancy and worsening postpartum.15,16 Many therapeutic options are contraindicated in pregnancy, although some patients discontinue therapies that may be safe.19 A 2015 Cochrane review showed no association between topical corticosteroids of any potency and birth defects, premature birth, or low Apgar score, although there was a possible association between extensive use of high-potency agents and low birth weight.23

Initial management of psoriasis during pregnancy includes emollients and low- to midpotency topical corticosteroids followed by ultraviolet B phototherapy. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, cyclosporine, and systemic corticosteroids may be considered after the first trimester for severe cases.17

Pregnancy-Specific Skin Conditions

| Condition | Clinical findings | Timing of onset and resolution | Fetal risk | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atopic eruption of pregnancy 1,24 | Pruritic eczematous papules with variation in distribution of lesions | Onset: first or second trimester Resolution: two to three months postpartum | Increased risk of atopic disease in infancy | Emollients Topical corticosteroids Oral antihistamines Ultraviolet B phototherapy |

| Polymorphic eruption of pregnancy 24–26 | Urticarial papules on the abdomen, particularly in striae gravidarum, but sparing umbilicus region; lesions coalesce into plaques | Onset: third trimester or immediately postpartum Resolution: within four to six weeks | None | Topical corticosteroids Oral antihistamines Oral corticosteroids in severe cases |

| Pemphigoid gestationis25–27 | Intense pruritus and polymorphic lesions that develop into bullae Starts on abdomen, spreading to the thighs, palms, soles | Onset: second or third trimester Resolution: late third trimester | Preterm birth Small for gestational age Passive antibody transfer leads to mild, transient lesions in 10% of newborns | Topical corticosteroids Oral antihistamines Oral corticosteroids in severe cases Fetal surveillance may be considered |

| Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy 24,26,28 | Severe pruritus without primary skin lesions Secondary excoriation Increased serum bile acids and liver function test results | Onset: second or third trimester Resolution: within six weeks postpartum | Preterm birth Intrapartum fetal distress Intrauterine fetal demise | Ursodeoxycholic acid (ursodiol) Oral antihistamines Fetal surveillance at diagnosis Delivery at 36 to 37 weeks of gestation |

| Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (impetigo herpetiformis)29,30 | Pustules on intertriginous areas that spread centrifugally to the extremities, sparing the face, palms, and soles Lesions coalesce into plaques and desquamate Usually nonpruritic | Onset: third trimester Resolution: postpartum | Placental insufficiency Fetal demise | Systemic corticosteroids Antibiotics for secondary infection Cyclosporine Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors (infliximab) Ultraviolet B phototherapy Fetal surveillance recommended |

ATOPIC ERUPTION OF PREGNANCY

Atopic eruption is a common benign, pruritic condition associated with immunologic changes in pregnancy that encompasses multiple entities, including prurigo of pregnancy, eczema of pregnancy, and pruritic folliculitis of pregnancy. Prurigo of pregnancy presents as erythematous papules on the extensor surfaces and abdomen, whereas eczema of pregnancy affects the face, chest, and flexural surfaces of the extremities. Pruritic folliculitis is less common and presents as diffuse, erythematous follicular papules on the abdomen, arms, chest, and back. Onset often occurs before the third trimester and symptoms resolve postpartum. There is no evidence of adverse perinatal outcomes; however, there may be an increased risk of atopic skin disease in infants.1 Treatment is symptomatic, using emollients, topical corticosteroids, and oral antihistamines, with ultraviolet B phototherapy available for severe cases.24

POLYMORPHIC ERUPTION OF PREGNANCY

Onset typically occurs in the third trimester or immediately postpartum. Urticarial lesions appear on the abdomen, particularly within the striae gravidarum but spare the umbilical region (differentiating it from pemphigoid gestationis).25,26 Lesions coalesce into plaques and spread to the buttocks and thighs, becoming generalized in severe cases. The rash can evolve into a polymorphic appearance with vesicular, eczematous, and targetoid lesions.24

Treatment is aimed at relieving pruritus using topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines. Oral corticosteroids may be used in severe cases. Lesions typically resolve within four to six weeks of onset without adverse maternal or fetal outcomes. Recurrence in subsequent pregnancies is uncommon except in a multiple pregnancy.24,25

PEMPHIGOID GESTATIONIS

Pemphigoid gestationis (see Figure 5 is a previous AFP article) occurs in 1 out of 60,000 pregnancies.27 Similar in pathogenesis to bullous pemphigoid, it is an autoimmune response against hemidesmosomal proteins affecting the dermis and epidermis.24,27 It occurs primarily in multiparous patients during the second or third trimester. Typical presentation is intense pruritus and polymorphic lesions that develop into bullae.25

Skin lesions start on the abdomen (including the umbilical region) and can spread to the thighs, palms, and soles. Bullae often resolve late in the third trimester but can flare up after delivery.27 Management includes topical corticosteroids and oral antihistamines, with more severe cases requiring oral corticosteroids. Recurrence is common and can be more severe in subsequent pregnancies or with other hormone fluctuations (e.g., oral contraceptive use).26,27

INTRAHEPATIC CHOLESTASIS OF PREGNANCY

Intrahepatic cholestasis occurs in 0.2% to 2% of pregnancies.28 It presents in the second or third trimester as debilitating pruritus affecting the palms and soles, with eventual generalized symptoms. There are no associated primary skin lesions, although secondary excoriation can develop. Jaundice occurs in 10% of patients two to four weeks after the onset of pruritus. Vitamin K deficiency and coagulopathy from malabsorption may also develop.24 Diagnosis is based on clinical history and elevation of serum bile acids. Other hepatic findings (e.g., bilirubin, alanine transaminases) may be mildly abnormal.24,26

Maternal prognosis is good, with symptoms resolving within six weeks postpartum. Multiple fetal complications due to high bile acid levels, including preterm delivery, intrapartum fetal distress, and fetal demise, have been reported.26,28 Treatment is aimed at alleviating pruritus and reducing serum bile acid concentrations with ursodeoxycholic acid (ursodiol); however, there are limited data indicating that this reduces adverse fetal outcomes.26 The risk of fetal adverse events correlates with the degree of bile acid elevation. Current guidelines recommend fetal monitoring at diagnosis, with delivery at 36 to 37 weeks of gestation.31,32

PUSTULAR PSORIASIS OF PREGNANCY

Pustular psoriasis of pregnancy (see Figure 6 in a previous AFP article), also called impetigo herpetiformis, is a rare disorder considered to be a variant of generalized pustular psoriasis.29 The condition appears in the third trimester as pustules on intertriginous areas that spread centrifugally to the extremities, sparing the face, palms, and soles. Lesions quickly coalesce into large plaques and desquamate.30 They are usually nonpruritic. Systemic complications may develop, including secondary infection, shock, hypocalcemia, and hypoalbuminemia. Fetal complications include increased risk of placental insufficiency and fetal demise. Fetal surveillance is recommended.29,30

Treatment includes high-dose systemic corticosteroids and antibiotics if needed for infected lesions. Cyclosporine or infliximab may be recommended for severe cases.30 Lesions typically resolve after delivery but may recur in subsequent pregnancies.

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Tunzi and Gray.5

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms pregnancy and skin conditions. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Also searched were the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality evidence reports, the Cochrane database, and Clinical Key. Search dates: January to March 2022, and November 2022.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Air Force, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.