This is a corrected version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(3):247-252

Related Letter to the Editor: Airflow Reversibility in Patients With Asthma

Related editorial: Reconsidering the Use of Race in Spirometry Interpretation

Patient information: See related handout on spirometry, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) affect more than 40 million Americans, cost more than $100 billion annually, and together constitute the fourth-leading cause of death in the United States. Distinguishing between asthma and COPD can be difficult; accurate diagnosis requires spirometry that demonstrates a characteristic pattern. Asthma is diagnosed if airway obstruction on spirometry is reversible (greater than 12% and greater than 200 mL improvement in forced expiratory volume in one second [FEV1]) with administration of bronchodilators or through the observation of bronchoconstriction (reduction in FEV1 of 20% or greater) with a methacholine challenge. COPD is diagnosed if airway obstruction (FEV1/forced vital capacity [FEV1/FVC] ratio less than 70%) on spirometry is not reversible with bronchodilators. Although not considered a separate diagnosis, asthma-COPD overlap can be a useful clinical descriptor for patients displaying diagnostic features of both diseases. In these cases, spirometry will show reversibility after administration of bronchodilators, which is consistent with asthma, and the persistent baseline airflow limitation that is more characteristic of COPD. Treatment should follow Global Initiative for Asthma guidelines and Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease guidelines. In patients with asthma-COPD overlap, pharmacotherapy should primarily follow asthma guidelines, but pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches specific to COPD may also be needed.

Asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) affect more than 40 million Americans,1,2 and together these two diseases contribute to more than $100 billion in annual health costs in the United States.3,4 In 2020, more than 4,000 Americans died of asthma, including at least 200 children,5 and more than 150,000 Americans die from COPD each year,6 making chronic lower respiratory disease the fourth-leading cause of death in the United States.7

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Do not diagnose or manage asthma or COPD without spirometry.13,14,17 | C | Choosing Wisely and international consensus guidelines |

| To diagnose asthma, pre- and postbronchodilator spirometry must show obstruction with FEV1 reversibility (> 12% and > 200 mL).13,17 | C | International consensus guidelines |

| Do not screen for chronic obstructive lung disease in asymptomatic adults.26 | B | USPSTF grade D recommendation |

| Diagnosis of COPD requires a lack of reversibility of obstruction (FEV1/FVC ratio < 70%) postbronchodilator.14 | C | International consensus guidelines |

| If overlap of asthma and COPD is suspected, pharmacotherapy should primarily follow asthma guidelines, but pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches to COPD should be considered.14 | C | International consensus guidelines |

Across the spectrum of obstructive lung disease, overlap has long been known to occur.8,9 Clinically, asthma and COPD coexist in many patients who demonstrate increased variability of airflow and incomplete reversibility of airway obstruction.10 Nearly 20% of patients with obstructive lung disease report having more than one lung condition, and this percentage increases with age.11

A new syndrome, asthma-COPD overlap, emerged in the early 2000s, with 15% to 45% of patients who have obstructive lung disease potentially qualifying for the distinction.12 However, major guidelines currently state that any reference to an overlap syndrome is a simple descriptor for patients who have features of both asthma and COPD and that the term does not refer to a specific disease entity.13 Physicians are encouraged to consider asthma and COPD as different disorders that share some common traits and clinical features and may coexist in an individual patient.14

This case-based review focuses on the distinguishing characteristics of asthma and COPD and presents a classic example of asthma-COPD overlap. Previous articles in American Family Physician discuss indications for and interpretation of office spirometry15 and also interpretation of pulmonary function tests.16 It is important to note that Choosing Wisely guidelines recommend that physicians do not diagnose or manage asthma or COPD without spirometry.13,14,17,18 For a full review of evidence-based treatment guidelines, refer to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Expert Panel recommendations, updated in 202017; the Global Initiative for Asthma guidelines, updated in 202213; and the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease guidelines, updated in 2023.14

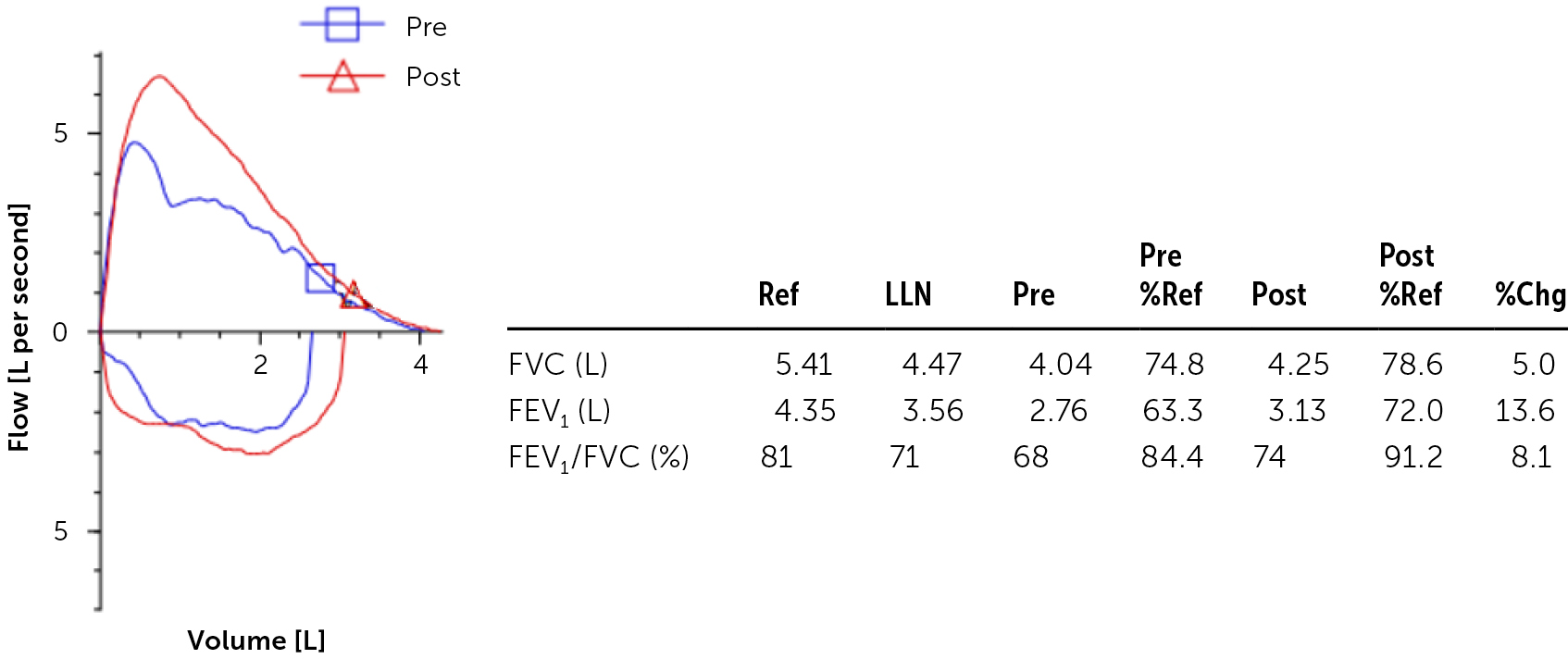

Case 1

A 42-year-old woman with a 12-month history of mild shortness of breath associated with some intermittent wheezing during upper respiratory tract infections presents for a follow-up visit. She does not smoke. She was not diagnosed with asthma as a child but used inhalers before physical education class and has a history of atopic dermatitis and allergic rhinitis. Office spirometry reveals a reduced forced expiratory volume in one second/forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) ratio of 68%, with improvement in FEV1/FVC to 74% and FEV1 improvement of 13.6% after a bronchodilator is given (Figure 1). [corrected]

Asthma is a heterogenous disease with respiratory symptoms such as wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, cough, and reduced expiratory lung function on spirometry that varies over time and in intensity.13 Risk factors for asthma include preterm birth, having respiratory symptoms since childhood, family history of asthma or allergies, personal history of allergic rhinitis or eczema, tobacco exposure, and obesity.13

Spirometry is central to distinguishing between asthma and other forms of obstructive lung disease.13,15 However, people with asthma often have normal lung function in the absence of an exacerbation, making a diagnosis on the first attempt challenging. If clinical suspicion for asthma or COPD is high despite normal results on initial spirometry, it is reasonable to repeat spirometry later. If the FEV1/FVC ratio is reduced on initial spirometry, it suggests an obstructive process, and a bronchodilator response should be tested. Substantial reversibility after bronchodilator use, defined as an increase in FEV1 of greater than 12% and greater than 200 mL, is consistent with asthma.13,17 A nonreversible or only mildly reversible obstructive pattern suggests an alternate diagnosis and may lead to additional evaluation.19

In a patient with a normal FEV1/FVC ratio, asthma cannot be confirmed or ruled out because of the intermittent nature of the disease process. The expiratory airflow limitation is variable over time and in magnitude. Bronchoprovocation testing such as the methacholine challenge is useful in this situation because it induces airway hyperresponsiveness. Methacholine is nebulized in increasing concentrations ranging from 0.016 to 16 mg per mL with each dose, followed by spirometry.20 A reduction in FEV1 of at least 20% at low levels of methacholine administration (i.e., 4 mg per mL) is consistent with asthma.17,20

Spirometry remains underused as a diagnostic tool, despite its proven superiority over history and physical examination alone.18 Barriers to the use of spirometry include a lack of knowledge of clinical practice guidelines recommending its use,21,22 low levels of comfort with conducting and interpreting the tests,23,24 and time and financial constraints.

For many adults with a diagnosis of obstructive lung disease but no formal testing, obtaining spirometry data can influence chronic disease management. A Canadian study found that 33% of adults with a preexisting asthma diagnosis without office spirometry or pulmonary function tests exhibited repeatedly normal spirometry results and were able to wean off respiratory medications.25 Of those, only 2.9% had resumed treatment after one year of follow-up.25

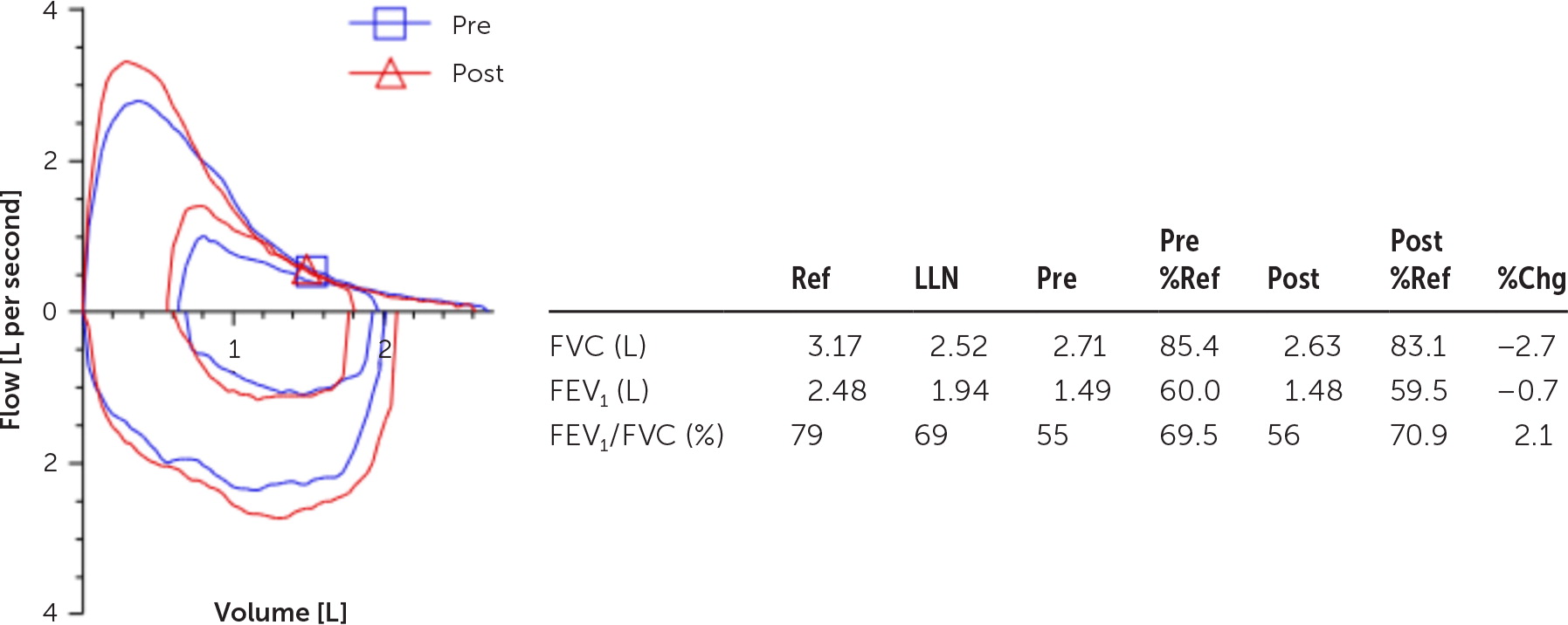

Case 2

A 54-year-old woman with a 30-pack-year smoking history presents with several months of chronic wheeze, productive cough, and decreased exercise tolerance due to shortness of breath. She is trying to quit smoking and says that she does not have significant exposure to environmental allergens. Office spirometry shows an FEV1/FVC ratio of 55% and little to no reversibility after administration of a bronchodilator (Figure 2).

Tobacco use is the most common risk factor for COPD; however, genetic factors such as alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency and other environmental exposures, including outdoor, occupational, and indoor air pollution, have also been recognized as risk factors for lung injury.14 In patients with respiratory symptoms such as dyspnea and chronic cough, history of recurrent lower respiratory tract infections, and history of exposure to risk factors, COPD should be considered.14 In patients without any of these respiratory symptoms, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force does not recommend using spirometry to screen for COPD.26

Histologically, COPD is characterized by chronic inflammation with eventual loss of small airways and lung elasticity with mucociliary dysfunction.14 Spirometry performed with prebronchodilator and postbronchodilator treatment values is essential to diagnosis because chronic respiratory symptoms can occur for other reasons. The hallmark of COPD is a persistent baseline FEV1/FVC ratio of less than 70% with a lack of reversibility post broncho dilator.14

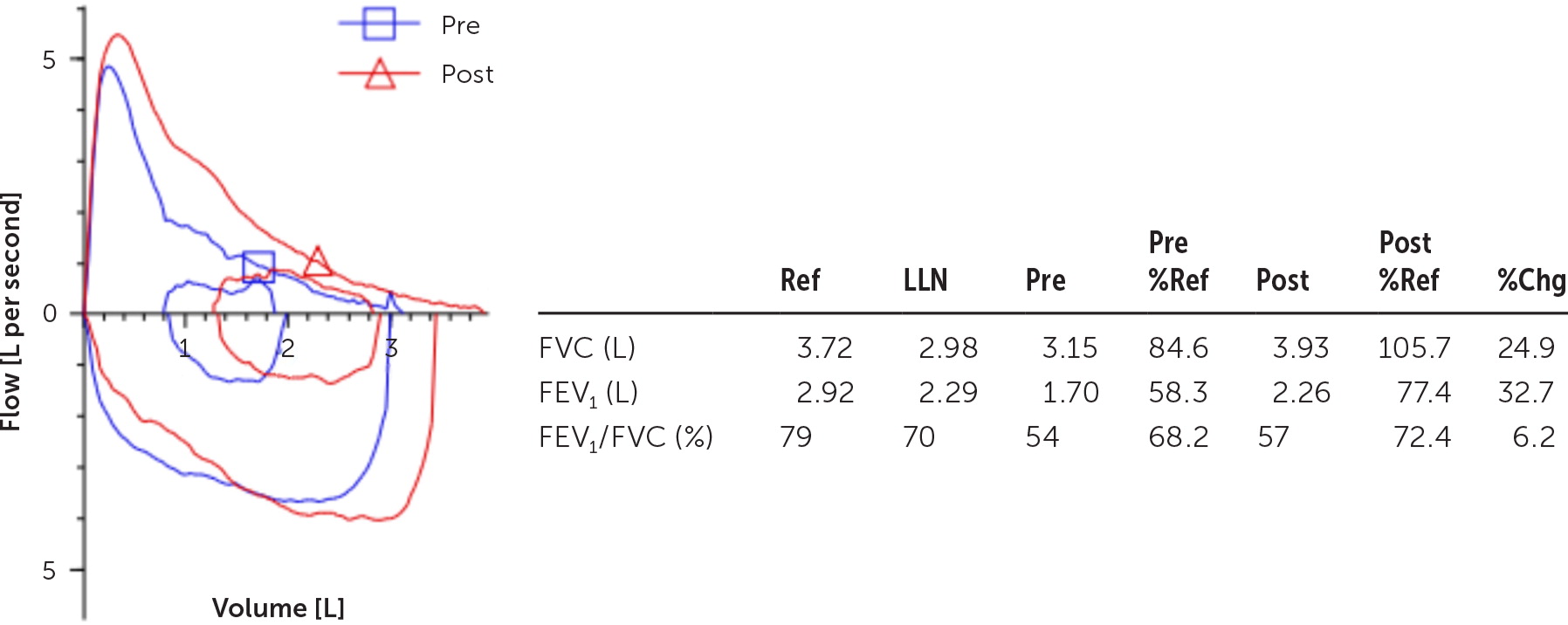

Case 3

A 67-year-old man with a 40-pack-year smoking history presents for a wellness visit. His medical history includes asthma and allergic rhinitis. He quit smoking 11 years ago after beginning to experience daily shortness of breath. He sees a pulmonologist, and a recently performed allergy panel showed high response to cat dander and dust mites. Office spirometry shows an FEV1/FVC ratio of 54% prebronchodilator and 57% postbronchodilator and an improvement in FEV1 of 560 mL, or 32.7% with bronchodilator (Figure 3).

| Characteristics | Asthma | COPD | Asthma-COPD overlap |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk factors | Preterm birth, tobacco exposure, obesity, allergic rhinitis, atopic dermatitis, family history of allergies or asthma13 | Tobacco use; genetic factors such as alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency; exposure to outdoor, occupational, and indoor air pollution14 | Combination of asthma and COPD risk factors is typical14 |

| Symptoms | Wheezing, shortness of breath, chest tightness, and cough that vary over time and in intensity13 | Dyspnea, chronic cough, recurrent lower respiratory tract infections14 | Combination of asthma and COPD symptoms is typical14 |

| Spirometry | May show obstruction (FEV1/FVC ratio reduced), but reversibility (> 12% and > 200 mL) is seen with bronchodilator use13 | Persistent FEV1/FVC ratio of < 70% with a lack of reversibility postbronchodilator14 | FEV1/FVC ratio reduction persists after bronchodilator, but reversibility is seen and meets asthma criteria14 |

Patients with active asthma are 12.5 times more likely to develop COPD as they get older 27 because of the years long airway remodeling process that leads to persistent obstruction,12 and about one in four patients with COPD have concomitant asthma.28 In an Australian study of 278 patients with obstructive lung disease, 37% of patients with asthma also met COPD criteria.29 In patients with an overlap of asthma and COPD, spirometry will demonstrate diagnostic features of both diseases. Persistently impaired baseline expiratory airflow limitation will coexist with FEV1 reversibility after bronchodilator use.

Asthma-COPD Overlap

Asthma-COPD overlap is not a distinct clinical entity but can be a useful descriptor for a patient who has clinical features and spirometry results consistent with both asthma and COPD13 (Table 11,2,13,14). In patients with asthma-COPD overlap, pharmacotherapy should primarily follow asthma guidelines,13 but pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic approaches to COPD may also be needed.14

Health maintenance is an important part of medical care for patients with chronic lung disease. This includes recommending smoking cessation and ensuring patients are current on vaccinations, including influenza, pneumococcus, tetanus, diphtheria, acellular pertussis, herpes zoster, and COVID-19. Pulmonary rehabilitation has also demonstrated improvements in quality of life and exercise tolerance for patients with COPD and asthma.14,30

Data Sources: A search was conducted using PubMed, Essential Evidence Plus, the Global Initiatives for Asthma (GINA) and Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) guidelines, and reference lists in retrieved articles. Key words: asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Search dates: May 2022 to January 2023.

The authors thank Trent W. McCain, MD, and Ravi T. Chandran, MD, pulmonologists with Prisma Health–Upstate, for their assistance in the procurement of the spirometry data used in the cases and figures in this article.