Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(3):264-272

Patient information: See related handout on polycystic ovary syndrome.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

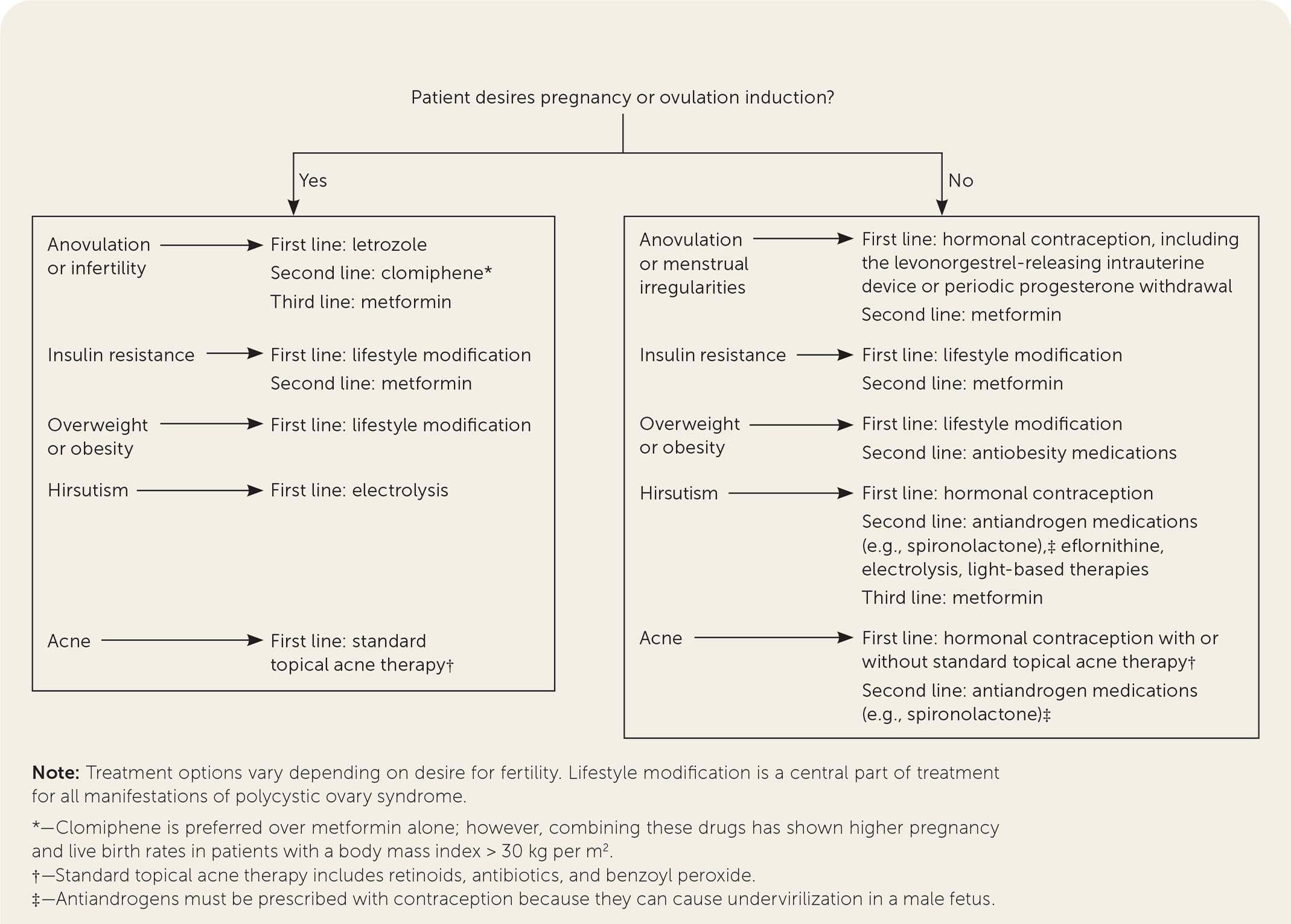

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrinopathy affecting women of childbearing age. Its complex pathophysiology includes genetic and environmental factors that contribute to insulin resistance in patients with this disease. The diagnosis of PCOS is primarily clinical, based on the presence of at least two of the three Rotterdam criteria: oligoanovulation, hyperandrogenism, and polycystic ovaries on ultrasonography. PCOS is often associated with hirsutism, acne, anovulatory menstruation, dysglycemia, dyslipidemia, obesity, and increased risk of cardiovascular disease and hormone-sensitive malignancies (e.g., at least a twofold increased risk of endometrial cancer). Lifestyle modification, including caloric restriction and increased physical activity, is the foundation of therapy. Subsequent management decisions depend on the patient’s desire for pregnancy. In patients who do not want to become pregnant, oral contraceptives are first-line therapy for menstrual irregularities and dermatologic complications such as hirsutism and acne. Antiandrogens such as spironolactone are often added to oral contraceptives as second-line agents. In patients who want to become pregnant, first-line therapy is letrozole for ovulation induction. Metformin added to lifestyle management is first-line therapy for patients with metabolic complications such as insulin resistance. Patients with PCOS are at increased risk of depression and obstructive sleep apnea, and screening is recommended.

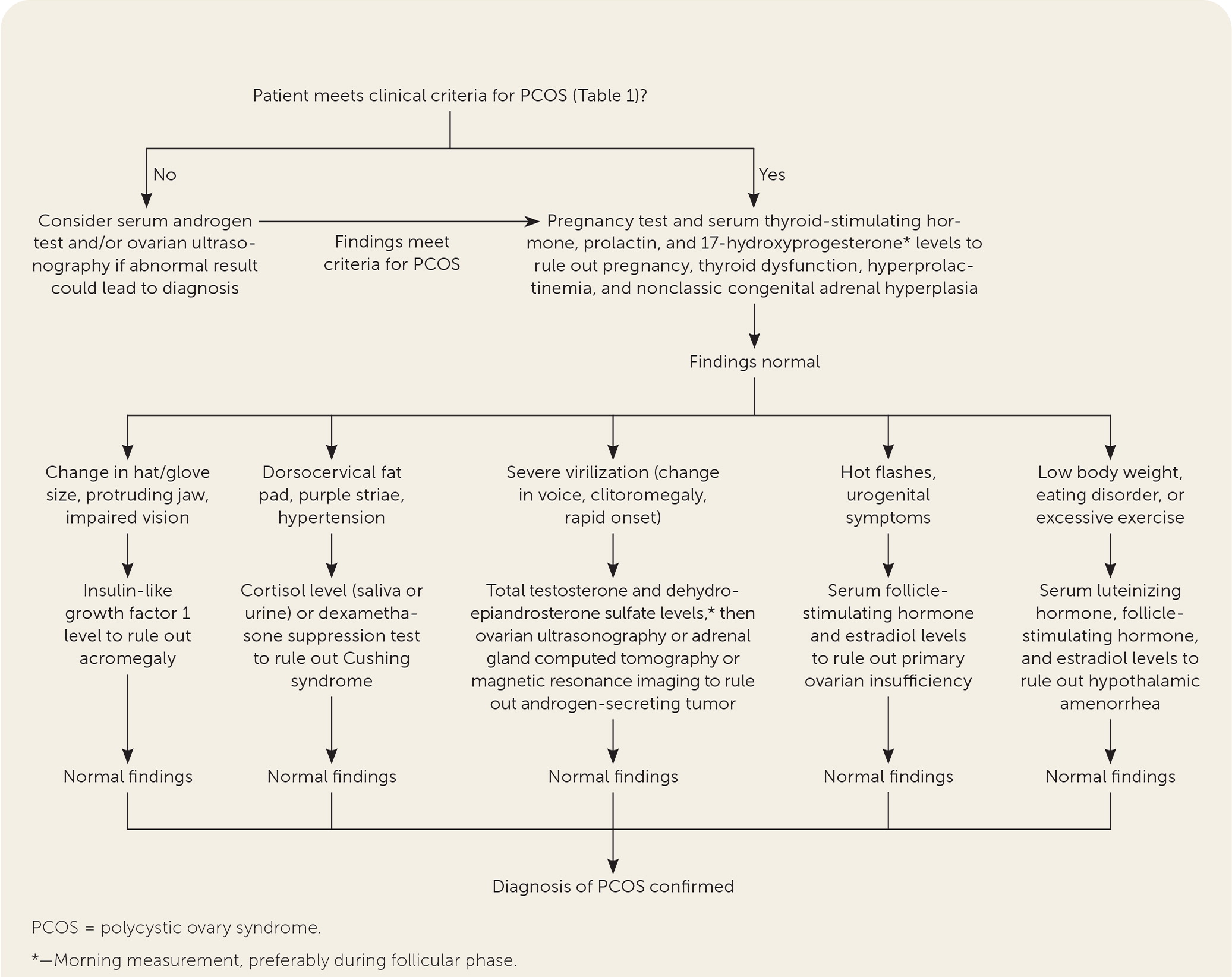

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is the most common endocrinopathy affecting women of childbearing age, with a prevalence between 8% and 13%.1 The pathophysiology of PCOS is complex and multifactorial, including genetic and environmental factors that contribute to deficient signaling in the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis and to ovarian and adrenal hyperandrogenism. Metabolic, dermatologic, and gynecologic features of PCOS are thought to be subsequent manifestations of insulin resistance. This article presents evidence-based answers to common questions about the diagnosis and management of PCOS. Figure 12–4 and Figure 22,4,5 are algorithms for the diagnosis and management of PCOS.

| In 2018, the International PCOS Network unanimously upheld the 2003 Rotterdam diagnostic criteria (Table 1). |

| Individuals with PCOS have a twofold to threefold increased prevalence of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus and a nearly fourfold increased prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea compared with those who do not have PCOS. |

| A 2019 Cochrane review concluded that lifestyle interventions for PCOS may reduce free androgen index, body weight, and body mass index and increase sex hormone–binding globulin levels. |

How Does PCOS Present?

Patients with PCOS may be asymptomatic, or they may have multiple metabolic, dermatologic, or gynecologic manifestations. Patients often present with signs of hyperandrogenism, irregular menses, or infertility.3,4 PCOS may be suspected after the incidental discovery of multiple ovarian cysts on ultrasonography, although most patients with incidentally detected polycystic ovaries on imaging do not have PCOS.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

In a meta-analysis of 24 studies of unselected adult women, approximately 13% had hirsutism, 11% had hyperandrogenemia, 28% had polycystic ovaries, and 15% had oligoanovulation.6 Polycystic ovaries are often nonpathologic, found in as many as 62% of patients with normal ovulation; this percentage declines with age.7 Even without PCOS, 9% to 14% of women of childbearing age have irregular menses, 10% have hirsutism, and 12% have infertility (i.e., the failure to conceive within 12 months of initiating unprotected intercourse).8–10 The prevalence of these conditions in the general population underscores the importance of meeting more than one of the Rotterdam criteria for diagnosis of PCOS.

What Is the Recommended Diagnostic Evaluation?

A clinical diagnosis of PCOS can generally be made with a history, a physical examination, and basic laboratory testing. There is no single diagnostic test for PCOS. Instead, clinical criteria are used, most commonly the 2003 Rotterdam criteria (Table 1). 4,11–14 After disorders with overlapping features have been excluded, the diagnosis of PCOS in adults requires the presence of at least two of the three Rotterdam criteria: oligoanovulation, hyperandrogenism, and polycystic ovaries on ultrasonography.

| Diagnosis | Testing |

|---|---|

| Acromegaly | Insulin-like growth factor 1 level |

| Androgen-secreting tumor | Calculated free testosterone level, free androgen index, or calculated bioavailable testosterone level, ideally using high-quality measurement techniques such as liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry or extraction chromatography immunoassays Dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate |

| Cushing syndrome | Cortisol level (saliva or urine) or dexamethasone suppression test |

| Exogenous androgens | Inhibin B level |

| Genetic defects in insulin action | A1C level, oral glucose tolerance test |

| Hyperprolactinemia | Prolactin level |

| Nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia | 17-hydroxyprogesterone level (measurement taken in the morning, preferably during follicular phase) |

| Primary hypothalamic amenorrhea | Follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, and estradiol levels, ideally on day 3 |

| Primary ovarian insufficiency | Follicle-stimulating hormone and estradiol levels |

| Thyroid disease | Thyroid-stimulating hormone level using third-generation test |

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

In 2018, the International PCOS Network unanimously upheld the 2003 Rotterdam criteria for diagnosis of PCOS.4 Hyperandrogenism can be diagnosed clinically in female patients by the presence of excessive acne, androgenic alopecia, hirsutism (terminal hair in a male-pattern distribution), or seborrhea.3,13 Patients can be evaluated biochemically for hyperandrogenism at least three months after stopping hormonal contraception.4,14

Evaluation of androgen levels in female patients is further complicated by the lack of standardized testosterone assays in the United States.15 The International PCOS Network recommends checking a calculated free testosterone level, free androgen index, or calculated bioavailable testosterone level, based on results of high-quality measurement techniques such as liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry or extraction chromatography immunoassays.4

How Is PCOS Diagnosed in Adolescents?

Because the Rotterdam criteria for PCOS in adults overlap with normal pubertal physiologic changes, the diagnosis in adolescents requires the presence of both oligoanovulation and hyperandrogenism for at least two years postmenarche.4,11 Ultrasound findings are not recommended as a diagnostic criterion in adolescents because polycystic ovaries can be a part of normal ovarian morphology in this age group. The International PCOS Network recommends waiting until at least eight years after menarche to consider ultrasound findings in the diagnosis of PCOS.4

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Oligoanovulation is common in the two years following menarche because of immaturity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis. By the third year postmenarche, regular cycles (occurring every 21 to 45 days) are established in 95% of adolescents, although irregular cycles can persist for up to five years even in those without PCOS.11,16

The International PCOS Network and the International Consortium of Pediatric Endocrinology agree that a diagnosis of PCOS in adolescents requires the presence of both oligoanovulation and hyperandrogenism for at least two years postmenarche.4,11 Polycystic ovary morphology, depending on the criteria used, is present in 30% to 40% of healthy adolescents.17

What Testing for Common Comorbidities Should be Performed?

| Assess glycemic status at baseline using OGTT, fasting plasma glucose level, or A1C level; repeat every one to three years* |

| Counsel patient about smoking cessation, if applicable |

| Obtain fasting lipid profile in all patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (repeat based on hyperlipidemia and global cardiovascular disease risk) |

| Perform blood pressure measurement annually (or more often based on global cardiovascular disease risk) |

| Screen for cancer according to universal recommendations (no additional screening recommended) |

| Screen for depression |

| Screen for sleep apnea |

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Patients with PCOS often have abnormal lipid levels, and the syndrome is independently associated with a 37% greater risk of hypertension, even after adjusting for other comorbidities.18,19 Individuals with PCOS have a twofold to threefold increased prevalence of prediabetes and type 2 diabetes mellitus, a nearly fourfold increased prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea, and a more than twofold increased prevalence of depression and anxiety compared with those who do not have PCOS.20–22

Although individuals with PCOS have at least a twofold increased risk of endometrial cancer compared with the general population, the absolute risk is relatively low.23 Routinely screening patients with PCOS for endometrial cancer is not recommended, but physicians should maintain a low threshold to evaluate for this malignancy. Transvaginal ultrasonography, endometrial biopsy, or both are recommended for patients with prolonged amenorrhea or abnormal uterine bleeding, especially those who are overweight.4

How Should Menstrual Irregularities in Patients With PCOS Be Treated?

Management of menstrual irregularities and other manifestations depends on the desire for pregnancy. In patients with PCOS and oligomenorrhea who do not want to get pregnant, menses should be induced at least every three to four months to decrease the risk of endometrial cancer.4 The first-line therapy is hormonal contraception. Long-term contraception with a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device or implant is ideal for patients who have difficulty adhering to oral contraceptives or those with contraindications to estrogen. In patients who do not desire contraception, periodic cyclic progesterone withdrawals (i.e., micronized progesterone, 200 mg orally per day for 10 to 14 days, or medroxyprogesterone, 5 to 10 mg orally per day for five to 10 days) are an option for inducing menses.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Nearly two-thirds of people with PCOS do not ovulate regularly.24 Although the optimal strategy for preventing endometrial cancer in these patients is unknown, the International PCOS Network recommends a practical approach that includes oral contraceptives or progestin therapy for induction of menses in patients with cycles longer than 90 days.4 A 2020 Cochrane review found that levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine devices are more effective than oral progesterone for reducing the risk of endometrial hyperplasia progressing to endometrial cancer.5

What Lifestyle Behaviors Should Be Recommended for Patients With PCOS?

Multicomponent lifestyle intervention, including nutritional counseling, calorie-restricted diet, exercise (Table 44) , and behavioral strategies, is recommended for all patients with PCOS who are overweight. No specific energy-equivalent diet appears to be superior; therefore, dietary changes should be tailored to food preferences. Weight loss exceeding 5% of initial body weight has been linked to clinical improvement in fertility and metabolic parameters, but dietary intervention improves health and quality of life even in the absence of weight loss. Physicians should explain the purpose of attempted weight loss, with attention to minimizing stigma and negative self-thoughts. Smoking cessation is recommended for all patients with PCOS who smoke.

| Age group | Physical activity | Strength training |

|---|---|---|

| Adolescents | 60 minutes per day of moderate- to vigorous-intensity activity in bouts of ≥ 10 minutes | At least three times per week |

| Adults 18 to 64 years of age | 150 minutes per week of moderate-intensity activity 75 minutes per week of vigorous-intensity activity | At least two times per week on nonconsecutive days |

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2018 systematic review found no significant differences among various diets for most outcomes. However, overall, diets aimed at restricting calories benefited patients with PCOS, independent of weight loss.3,4 A 2019 Cochrane review concluded that lifestyle interventions may reduce free androgen index, body weight, and body mass index (BMI) and increase sex hormone–binding globulin levels.25 No studies included in the systematic reviews addressed the effect of lifestyle interventions on live birth or miscarriage. The American Society for Reproductive Medicine and the European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology recommend that patients receive counseling on lifestyle modification, including modest weight loss and physical activity, before interventions for ovulation induction are considered.26 A secondary analysis of two randomized controlled trials found that delaying ovulation-inducing pharmacotherapy until after patients achieve approximately 6% weight loss in a 16-week intervention resulted in a statistically significant increase in rates of ovulation and live birth.27

What Is the First-Line Drug Therapy for Metabolic Manifestations of PCOS?

Metformin is the first-line drug therapy for metabolic manifestations of PCOS such as insulin resistance, although it is likely inferior to lifestyle modification, especially for prevention of diabetes.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2018 systematic review found that metformin (median daily dosage of 1,500 mg) is superior to placebo for the management of weight and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels in patients with PCOS and a BMI greater than 25 kg per m2 and for the management of fasting glucose, cholesterol, and triglyceride levels regardless of BMI.4 An eight-month randomized controlled trial showed that a 2,500-mg daily dosage has minimal additional benefits over a 1,500-mg daily dosage.28

What Is the First-Line Drug Therapy for Menstrual Manifestations of PCOS?

Oral contraceptives are first-line drug therapy for oligomenorrhea. The lowest effective estrogen dose, such as 20 to 30 mcg of ethinyl estradiol or its equivalent, is preferred, with attention to contraindications in the general population and to PCOS-specific risk factors such as elevated BMI, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension. Higher-dose (35 mcg) ethinyl estradiol preparations should not be considered for first-line therapy because of adverse effects, including increased risk of venous thromboembolism.4 In adolescents, oral contraceptives with 30 mcg of ethinyl estradiol may preserve peak bone mineral density, although the effect on fracture risk is unknown.29

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use may assist when reviewing comorbidities and choosing an optimal contraceptive strategy in patients with PCOS.30 Metformin should be considered second-line drug therapy for oligomenorrhea.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2014 systematic review and meta-analysis found that the estrogen dose and progestin type used in an oral contraceptive do not influence the decline of total and free testosterone levels.31 However, a 2018 systematic review suggests that oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel, norethindrone, or norgestimate are associated with the lowest risk of thromboembolism.4 A systematic review found that oral contraceptives with less than 30 mcg of ethinyl estradiol are associated with lower bone mineral density in adolescents, although an increase in fracture risk was not observed.29 Oral contraceptives are superior to metformin for menstrual regulation in adolescents and adults.4

What Is the First-Line Drug Therapy for Dermatologic Manifestations of PCOS?

Oral contraceptives are first-line drug therapy for hirsutism, acne, and androgen-related alopecia, with similar effectiveness among various preparations. Antiandrogens such as spironolactone are second-line drug therapy for hirsutism and acne but should not be used without contraception because it can cause undervirilization in a male fetus. Metformin is considered third-line therapy.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

The authors of a 2018 systematic review recommend considering the addition of antiandrogens such as spironolactone to treat hirsutism, acne, and androgen-related alopecia in PCOS only if at least six months of oral contraceptive use and cosmetic therapies alone do not sufficiently improve symptoms.4 When oral contraceptives are contraindicated or poorly tolerated, another form of effective contraception should be used with antiandrogens.4 A 2020 Cochrane review concluded that metformin may be less effective than oral contraceptives for reducing hirsutism in patients with PCOS, particularly in those with a BMI of 25 to 30 kg per m2.32

What Is the First-Line Drug Therapy for Women With PCOS Who Want to Become Pregnant?

Letrozole is preferred over clomiphene for ovulation induction.4 Patients should be counseled about the elevated risk of a multiple pregnancy with use of either of these drugs.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A 2018 systematic review concluded that letrozole, an aromatase inhibitor, is superior to clomiphene with respect to the ovulation rate per patient, pregnancy rate per patient and per cycle, and live birth rate per patient.4 The systematic review and a related meta-analysis found no difference between letrozole and clomiphene regarding the ovulation rate per cycle, multiple pregnancy rate per patient, or miscarriage rate per patient.4,33 A 2014 randomized controlled trial found that the rate of multiple pregnancy was 3.4% with letrozole and 7.4% with clomiphene, although the difference did not reach statistical significance.34 Table 5 compares letrozole and clomiphene.33–35

| Comparison | Letrozole | Clomiphene |

|---|---|---|

| Drug class | Aromatase inhibitor | Selective estrogen receptor modulator |

| Line of therapy for ovulation induction | First line | Second line |

| Typical treatment | 2.5 mg orally per day for five days Typically start on day 3 of menstrual cycle (day 2 to 5 is acceptable)* If pregnancy is not achieved, repeat the above dosage; if still no success, increase to 5 mg daily Maximum dosage is 7.5 mg daily | 50 mg orally per day for five days Typically start on day 3 of menstrual cycle (day 2 to 5 is acceptable)* May repeat up to six cycles Maximum dosage is 100 mg daily |

| Approximate monthly cost† | $2 (generic) or $125 (brand) for five 2.5-mg tablets | $6 (generic; brand no longer available) for five 50-mg tablets |

| Live birth rate‡ | Higher with letrozole vs. clomiphene | |

| Risk of multiple pregnancy§ | No statistical difference between letrozole and clomiphene | |

| Risk of miscarriage | No statistical difference between letrozole and clomiphene |

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Williams, et al.2; Radosh36; Richardson37; and Hunter and Sterrett.38

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key term polycystic ovary syndrome. The search included meta-analyses, systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. A search was also performed using Essential Evidence Plus. Search dates: March and May 2022 and January 2023.