Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(3):273-281

Patient information: See related handout on posttraumatic stress disorder, written by the authors of this article.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

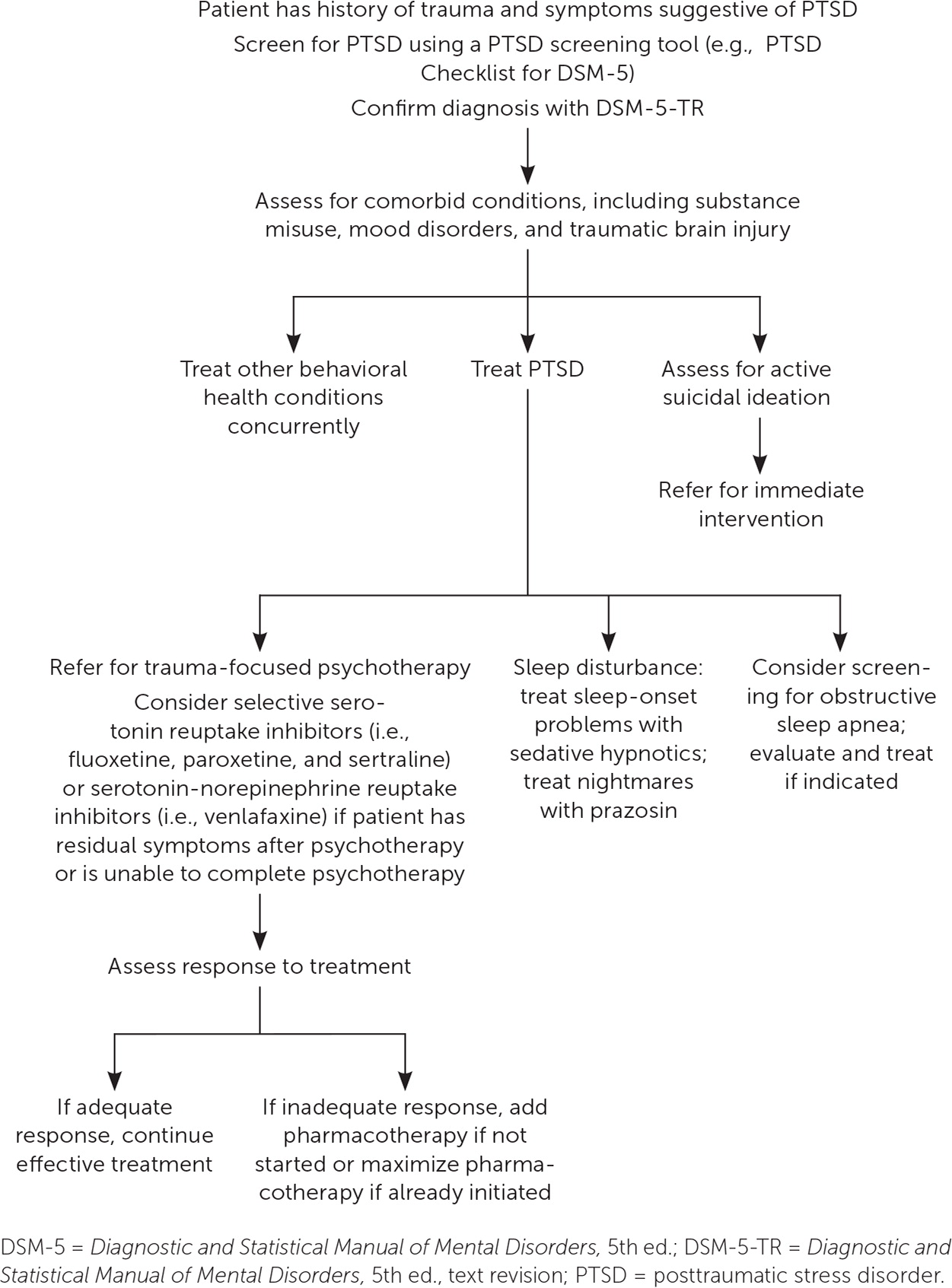

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is common, with a lifetime prevalence of approximately 6%. PTSD may develop at least one month after a traumatic event involving the threat of death or harm to physical integrity, although earlier symptoms may represent an acute stress disorder. Symptoms typically involve trauma-related intrusive thoughts, avoidant behaviors, negative alterations of cognition or mood, and changes in arousal and reactivity. Assessing for past trauma in patients with anxiety or other psychiatric illnesses may aid in diagnosing and treating PTSD. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed., text revision provides diagnostic criteria, and the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 uses these diagnostic criteria to help physicians diagnose PTSD and determine severity. First-line treatment of PTSD involves psychotherapy, such as trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy. Pharmacotherapy is useful for patients who have residual symptoms after psychotherapy or are unable or unwilling to access psychotherapy. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (i.e., fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline) and the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine effectively treat primary PTSD symptoms. The addition of other pharmacotherapy, such as atypical antipsychotics or topiramate, may be helpful for residual symptoms. Patients with PTSD often have sleep disturbance related to hyperarousal or nightmares. Prazosin is effective for the treatment of PTSD-related sleep disturbance. Clinicians should consider testing patients with PTSD for obstructive sleep apnea because many patients with PTSD-related sleep disturbance have this condition. Psychiatric comorbidities, particularly mood disorders and substance use, are common in PTSD and are best treated concurrently.

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is common, occurring in 6% of individuals.1 It is often undetected in patients presenting to primary care.2,3 PTSD can occur in civilian and veteran populations in response to a broad range of traumatic events. PTSD affects people of all ages, and women are twice as likely to receive a diagnosis compared with men.4 Symptoms of PTSD typically involve trauma-related intrusive thoughts, avoidant behaviors, negative alterations of cognition or mood, and changes in arousal and reactivity.5 Two-thirds of patients with PTSD report moderate to severe symptoms.2 PTSD may increase the risk of cardiovascular disease and other medical conditions commonly seen in primary care.6

PTSD can be treated in primary care, especially in systems with integrated behavioral health services.7 PTSD presents similarly in people with and without military service, but there are differences. The high prevalence of PTSD shows the importance of diagnosis and treatment by family physicians.

Natural History

PTSD may develop at least one month after a qualifying traumatic event, specifically an event that involves the threat of death or harm to physical integrity. Qualifying traumatic events are common across all ages and socioeconomic groups.8 The pathophysiology of PTSD appears to involve impairment in traumatic memory consolidation, leading to maladaptive neuropsychological responses.9 Patients often report reexperiencing their trauma, which triggers physiologic and psychological responses that present as primary symptoms of the disorder. Although trauma is common, affecting one-half of adults, less than 10% of patients with traumatic experiences develop PTSD.9–11 People with more exposure to traumatic events are more likely to develop and have persistent PTSD and report severe PTSD symptoms.10 This association between cumulative trauma and PTSD partially explains why populations at high risk of recurrent trauma carry a higher PTSD disease burden. For example, patients who identify as LGBTQIA (lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer [or questioning], intersex, asexual) are more likely to experience trauma and develop PTSD compared with their peers.12

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed., text revision (DSM-5-TR) lists the diagnostic criteria for PTSD.5 However, patients often report symptoms beyond the core symptoms in the diagnostic criteria. Although presenting symptoms of PTSD often involve psychological symptoms such as hyperarousal, reexperiencing traumatic events, and sleep disturbance, patients often report somatic complaints, such as gastrointestinal distress or musculoskeletal problems.9 Psychological symptoms of PTSD can be mistaken for anxiety or mood disorders, which are often comorbid with PTSD. This makes diagnosing PTSD challenging and requires physicians to maintain a low threshold for asking about past trauma for a range of symptoms without other psychological or physiologic explanations.

Screening

Because of the considerable overlap between PTSD and other behavioral health disorders, differentiating PTSD from other disorders can be challenging. Routinely inquiring about past trauma in new patients with undifferentiated anxiety or mood symptoms may aid in diagnosing and treating PTSD. Despite the high prevalence of PTSD, there are no standardized recommendations for universal adult screening. It is recommended that all veterans be screened for PTSD annually for five years after separation from service, then once every five years thereafter.13 A previous American Family Physician article on care of the military veteran has more information on screening (https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2019/1101/p544.html).

Prevention

Although intervention after trauma is an opportunity to prevent PTSD, there is no consensus on how to prevent PTSD for patients with traumatic exposures. A single session debriefing is not effective at preventing PTSD development.14 However, early psychological treatments may be helpful. A Cochrane review found low-certainty evidence that multiple early interventions reduced the likelihood of PTSD diagnosis at three to six months after trauma (number needed to treat = 12; 95% CI, 8 to 67), but these interventions may not be effective at one year.15 Many medications have been proposed to reduce the likelihood of PTSD after trauma, but most show no evidence of benefit. A 2022 Cochrane review found that hydrocortisone, propranolol, and gabapentin do not prevent PTSD development after a traumatic exposure.16

Acute Stress Disorder

Acute stress disorder presents with symptoms similar to those of PTSD but occurs exclusively within four weeks of traumatic exposure. It is a risk factor for PTSD; one-half of people diagnosed with acute stress disorder will develop PTSD. However, most individuals with PTSD are not diagnosed with acute stress disorder.17 Patients with acute stress disorder should receive trauma-focused cognitive behavior therapy because it reduces the risk of long-term symptoms and PTSD.18 Patients with symptoms of acute stress disorder lasting longer than one month should be evaluated for PTSD.

Diagnosis of PTSD

Table 1 lists the DSM-5-TR criteria for PTSD.5 Trauma exposure is the hallmark criterion of PTSD. Traumas vary, but interpersonal violence, such as sexual assault, physical assault, or military combat, is most likely to lead to PTSD development.19 Patients do not need to have experienced the trauma directly to meet the criteria. Indirect exposure by witnessing an event or exposure to details of an event can be sufficiently traumatic. Criteria B, C, D, and E organize the symptoms of PTSD. Persistent psychological impairments include hyperarousal, avoidance, intrusive thinking, and negative cognition or mood related to the past traumatic experience. Many patients with PTSD have sleep impairment, and symptoms typically present as difficulty falling or staying asleep and sleep disturbances, including nightmares.

A. Exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence in one (or more) of the following ways:

Note: Criterion A4 does not apply to exposure through electronic media, television, movies, or pictures, unless this exposure is work related. |

B. Presence of one (or more) of the following intrusion symptoms associated with the traumatic events, beginning after the traumatic events occurred:

|

C. Persistent avoidance of stimuli associated with the traumatic events, beginning after the traumatic events occurred, as evidenced by one or both of the following:

|

D. Negative alterations in cognitions and mood associated with the traumatic events, beginning or worsening after the traumatic event occurred, as evidenced by two (or more) of the following:

|

E. Marked alterations in arousal and reactivity associated with the traumatic events, beginning or worsening after the traumatic events occurred, as evidenced by two (or more) of the following:

|

| F. Duration of the disturbance (Criteria B, C, D, and E) is more than 1 month. |

| G. The disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning. |

| H. The disturbance is not attributable to physiological effects of a substance (e.g., medication, alcohol) or another medical condition. |

| Specify whether: With dissociative symptoms: The individual’s symptoms meet the criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder, and in addition, in response to the stressor, the individual experiences persistent or recurrent symptoms of either of the following:

Note: to use this subtype, the dissociative symptoms must not be attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (e.g., blackouts, behavior during alcohol intoxication) or another medical condition (e.g., complex partial seizures). |

| Specify if: With delayed expression: If the full diagnostic criteria are not met until at least 6 months after the event (although the onset and expression of some symptoms may be immediate). |

Although diagnosis of PTSD is based on the DSM-5-TR criteria, several assessment tools have been created based on these criteria. The diagnostic standard for office-based assessment of PTSD is the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale for DSM-5 (CAPS-5), a 30-item diagnostic tool based on DSM-5 criteria; it takes up to one hour to administer.20 The 20-item PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) is a self-reported scale validated against the CAPS-5 that can diagnose PTSD and grade severity.21 The PCL-5 is validated for use in civilian and military populations and is available at https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp.22 Initial and subsequent evaluations should include suicide risk assessment because PTSD is a strong risk factor for suicidal ideation and suicide completion.23 A diagnostic tool using DSM-5 criteria is also available at https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/10211/dsm-5-criteria-posttraumatic-stress-disorder.

Treatment of Psychological Symptoms

PSYCHOTHERAPY

Table 2 presents an overview of PTSD treatment. Psychotherapy is the preferred initial treatment for PTSD and should be offered to all patients.25–28 Trauma-focused psychotherapies have high-quality empirical support in the literature and show a superior reduction in PTSD symptoms with a large effect size compared with pharmacotherapy or non–trauma-focused therapies.29–33 Trauma-focused psychotherapy centers around the experience of past traumatic events to aid in psychological processing of the events and changing unhelpful or mal-adaptive beliefs about past trauma.34 Trauma-focused psychotherapy is a broad category that represents a wide range of manualized therapies, such as cognitive behavior therapy, cognitive therapy, prolonged exposure, and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing. Trauma-focused psychotherapy usually consists of weekly to biweekly sessions lasting 60 to 90 minutes over a period of six to 12 weeks. Most trauma-focused psychotherapy modalities are proven effective and recommended by the American Psychological Association’s clinical practice guideline.26 If patients do not have access to trauma-focused psychotherapy, non–trauma-focused therapies can be effective, although to a lesser extent. Cognitive behavior therapy for PTSD delivered via the internet is effective, although there is less evidence to support its use.35

| Psychotherapy | Pharmacotherapy | Concurrent treatment |

|---|---|---|

| First line: trauma-focused psychotherapy Strongly recommended by the American Psychological Association: prolonged exposure, cognitive processing therapy Conditionally recommended by the American Psychological Association: brief eclectic psychotherapy, narrative exposure therapy, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing | First line: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (i.e., fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (i.e., venlafaxine) | Sleep disturbance: prazosin Obstructive sleep apnea: screen and treat Comorbidities: treat according to specific disorder |

| If trauma-focused psychotherapy is unavailable: stress inoculation training, present-centered therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy | Second line: mirtazapine, tricyclic antidepressants (i.e., imipramine, amitriptyline) |

INITIAL PHARMACOTHERAPY

Pharmacotherapy is important in the treatment of PTSD. Despite the effectiveness of trauma-focused psychotherapy, up to one-half of patients with PTSD have residual symptoms after treatment.25 Pharmacotherapy is also important for patients who lack access to behavioral health services or prefer pharmacotherapy over psychotherapy. Patients with co-occurring major depressive disorder may be less likely to respond to psychotherapy without pharmacotherapy.36 Therefore, pharmacotherapy is a first-line treatment option for these patients.27

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, including fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline, and the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor venlafaxine are the most effective pharmacologic treatments for PTSD. Paroxetine and fluoxetine are moderately effective in reducing PTSD symptoms.25–28,33,37 Paroxetine and venlafaxine are moderately effective in inducing PTSD remission.33 Sertraline is less effective than paroxetine and venlafaxine for reducing symptoms, and there are no data supporting its use for inducing remission. Despite the benefits of paroxetine, patients are more likely to discontinue this medication due to tolerability issues.37

When starting pharmacotherapy, clinicians should discuss medication risks and the probable need for repeated dose increases. By assessing patient response regularly, physicians can titrate medications to the maximum tolerated dose. Patients who do not respond to treatment after eight to 12 weeks of taking a medication at the maximum tolerated dose should switch to another medication.25

ADDITIONAL PHARMACOTHERAPY

Other medications may be helpful as alternate or supplemental therapy for patients who experience only partial benefit from pharmacotherapy. The atypical antipsychotics risperidone (Risperdal) and olanzapine (Zyprexa) slightly improve PTSD-related symptoms.33 Risperidone has the most evidence, mainly in the military population.38,39 Patients taking risperidone may have extrapyramidal symptoms or movement disorder–related toxicity, and both risperidone and olanzapine could cause significant metabolic-related toxicity.40 Aripiprazole appears to be effective for PTSD treatment and has fewer metabolic risks.40–42

Treatment of Sleep Disturbance

PSYCHOTHERAPY

PHARMACOTHERAPY

Sedative hypnotic agents, such as benzodiazepines, the nonbenzodiazepine z-drugs (i.e., eszopiclone [Lunesta], zaleplon, and zolpidem), and trazodone may help patients with sleep disturbance. The misuse potential and chronic long-term effects of benzodiazepines make them less desirable. Patients with PTSD who are taking sedative hypnotic agents are less likely to respond to cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia.47 PTSD-related sleep impairment is often chronic, increasing the risk of long-term sedative hypnotics use. Cognitive behavior therapy for insomnia is recommended before prescribing these medications.27

If patients experience mid-sleep awakening due to hyper-arousal or nightmares, the alpha1 antagonist prazosin may reduce symptoms by decreasing sympathetic nervous tone during sleep. [corrected] A recent randomized controlled trial showed that prazosin did not reduce nightmare occurrence or improve sleep quality compared with placebo, but a systematic review that included this trial demonstrated that prazosin reduced nightmares without improving overall symptoms or sleep quality.48,49

OBSTRUCTIVE SLEEP APNEA

Obstructive sleep apnea is common in patients with PTSD. Three-fourths of patients with PTSD have sleep apnea on polysomnography, and nearly one-half have at least moderate obstructive sleep apnea.50 Continuous positive airway pressure reduces nightmares and improves daytime symptoms in patients with PTSD and obstructive sleep apnea.51 Adherence to continuous positive airway pressure is lower when patients have PTSD, increasing the importance of monitoring. Physicians should consider asking about barriers to continuous positive airway pressure adherence and offer counseling.50 Oral mandibular repositioning devices are effective for patients with mild to moderate obstructive sleep apnea. In a study of veterans with PTSD, oral devices were nearly as effective as continuous positive airway pressure and were used for an average of two hours more each night.52 Patients unable to adhere to continuous positive airway pressure may benefit from these oral devices as alternative therapies.

Behavioral Health Comorbidities

Most patients with PTSD have comorbidities. Physicians should evaluate for and treat behavioral health comorbidities concurrently when diagnosing patients with PTSD. Diagnosis of additional disorders should not preclude treatment of PTSD.27 Depression co-occurs in up to one-half of all patients with PTSD and is more common in veterans and survivors of interpersonal violence.53 Patients with PTSD and depression are more likely to require pharmacotherapy to improve symptoms.36

Substance use disorders are common in patients with PTSD and 40% of patients with PTSD meet criteria for alcohol use disorder.54 Patients with PTSD and substance use report more functional impairment and have twice the suicide risk of patients with PTSD alone.55,56 PTSD and substance use disorder should be treated concurrently.57 Trauma-focused psychotherapy may be less effective when PTSD is complicated by substance use.58 However, a recent study shows that cognitive processing therapy reduces PTSD symptoms and drinking in patients with alcohol use disorder.59

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Warner, et al.24

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed using the key terms PTSD, trauma-related disorders, treatment, psychological treatment, pharmacotherapy, and comorbidities. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Effective Healthcare Reports and the Cochrane database were also searched. We reviewed guidelines from the American Psychological Association, American Psychiatric Association, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Studies that used race and/or gender as patient categories but did not define how these categories were assigned were not included in our final review. Search dates: March 28, 2022, and December 16, 2022.