Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(6):585-596

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Acute abdominal pain, defined as nontraumatic abdominal pain lasting fewer than seven days, is a common presenting concern with a broad differential diagnosis. The most common causes are gastroenteritis and nonspecific abdominal pain, followed by cholelithiasis, urolithiasis, diverticulitis, and appendicitis. Extra-abdominal causes such as respiratory infections and abdominal wall pain should be considered. Pain location, history, and examination findings help guide the workup after ensuring hemodynamic stability. Recommended tests may include a complete blood count, C-reactive protein, hepatobiliary markers, electrolytes, creatinine, glucose, urinalysis, lipase, and pregnancy testing. Several diagnoses, such as cholecystitis, appendicitis, and mesenteric ischemia, cannot be confirmed clinically and typically require imaging. Conditions such as urolithiasis and diverticulitis may be diagnosed clinically in certain cases. Imaging studies are chosen based on the location of pain and index of suspicion for specific etiologies. Computed tomography with intravenous contrast media is often chosen for generalized abdominal pain, left upper quadrant pain, and lower abdominal pain. Ultrasonography is the study of choice for right upper quadrant pain. Point-of-care ultrasonography can aid in the prompt diagnosis of several etiologies of acute abdominal pain, including cholelithiasis, urolithiasis, and appendicitis. In patients who have female reproductive organs, diagnoses such as ectopic pregnancy, pelvic inflammatory disease, and adnexal torsion should be considered. If ultrasonography results are inconclusive in pregnant patients, magnetic resonance imaging is preferred over computed tomography when available.

Acute abdominal pain is defined as pain lasting fewer than seven days and accounts for up to 10% of emergency department visits.1 In one large study of patients presenting to the emergency department with recent abdominal pain, 20 conditions accounted for up to 70% of the causes, but more than 150 etiologies were diagnosed.2 Acute gastroenteritis (10.8%) and non-specific abdominal pain (10.4%) were the most common diagnoses, followed by cholelithiasis (4.5%), urolithiasis (4.3%), diverticulitis (3.8%), and appendicitis (3.8%).2 Extra-abdominal causes were common. About 10% of patients had a urinary etiology, and 10% of patients 65 years and older had a respiratory cause.2 Table 1 lists causes of acute abdominal pain by location.3

| Pain location | Possible diagnoses |

|---|---|

| Any location | Common: constipation, hernia, herpes zoster, IBD, IBS or functional abdominal pain, mesenteric adenitis, peritonitis, and small bowel obstruction Less common: abdominal wall pain, mesenteric ischemia, neoplasm, opioid withdrawal, sickle cell crisis, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis Pregnancy: placental abruption, uterine rupture Rare: rectus sheath hematoma |

| Epigastric | Common Biliary: cholangitis, cholecystitis, cholelithiasis Gastric: esophagitis, gastric or duodenal ulcer/perforation, gastritis Pancreatic: mass, pancreatitis Common, normally associated with chest pain Cardiac: angina, myocardial infarction, pericarditis Less common Vascular: aortic dissection, mesenteric ischemia, ruptured aortic aneurysm Rare Vascular: median arcuate ligament syndrome |

| Left lower quadrant | Common Colonic: colitis, diverticulitis, IBD, IBS Gynecologic: adnexal torsion, ectopic pregnancy, ovulation pain/ovarian cyst rupture, PID Renal: pyelonephritis, urolithiasis Rare Colonic: appendicitis (situs inversus) |

| Left upper quadrant | Common Gastric: esophagitis, gastric or duodenal ulcer/perforation, gastritis Pancreatic: mass, pancreatitis Pulmonary: pneumonia Renal: nephrolithiasis, pyelonephritis Common, normally associated with chest pain Cardiac: angina, myocardial infarction, pericarditis Less common Vascular: aortic dissection, mesenteric ischemia Rare Vascular: splenic vein thrombosis |

| Periumbilical | Common Colonic: early appendicitis, IBS Gastric: esophagitis, gastric or duodenal ulcer/perforation, gastritis Less common Vascular: aortic dissection, mesenteric ischemia, ruptured aortic aneurysm Umbilical and incisional hernia |

| Right lower quadrant | Common Colonic: appendicitis, colitis, diverticulitis, IBD, IBS Gynecologic: adnexal torsion, ectopic pregnancy, ovulation pain/ovarian cyst rupture, PID Renal: pyelonephritis, urolithiasis Rare Colonic: epiploic appendagitis |

| Right upper quadrant | Common Biliary: cholangitis, cholecystitis, cholelithiasis Pulmonary: embolus, pleurisy, pneumonia Renal: nephrolithiasis, pyelonephritis Less common Colonic: appendicitis, colitis, diverticulitis Hepatic: abscess, hepatitis, mass Rare Gynecologic: Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome (inflammation of the liver capsule secondary to PID) |

| Suprapubic | Common Colonic: appendicitis, colitis, diverticulitis, IBD, IBS Gynecologic: ectopic pregnancy, PID Renal: cystitis, pyelonephritis, urinary retention, urolithiasis |

| Other causes of acute abdominal pain not mentioned above | Rare: abdominal migraine, angioedema (hereditary and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor induced), gastric or intestinal volvulus, heavy metal poisoning, immunoglobulin A vasculitis, intussusception, Meckel diverticulum (diverticulitis or obstruction), porphyria, renal or splenic infarction |

Diagnosis

Clinicians should rapidly identify patients with hemodynamic instability, signs of peritonitis, or pain out of proportion to physical examination findings because these patients often need urgent resuscitation or surgery.4 Once hemodynamic stability has been confirmed, history and examination help narrow the differential diagnosis. Table 2 lists the value of selected symptoms and signs in presentations of acute abdominal pain.3,5–14 Approximately 10% of primary care patients with abdominal pain of any duration require immediate treatment.15 That proportion in patients with acute pain is likely higher. Delayed or missed diagnoses are associated with increased morbidity and mortality.16 For example, immunocompromised patients are more likely to have atypical presentations and opportunistic infections, which can lead to a delay in diagnosis and resulting complications.17

| Finding | LR+ | LR− | 5% pretest probability (%) | 25% pretest probability (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finding present | Finding absent | Finding present | Finding absent | |||

| Abdominal wall pain (chronic setting)5 | ||||||

| Carnett sign | 6.5 | 0.25 | 25 | 1 | 68 | 8 |

| Combination of localized pain (fingertip) or fixed pain location and superficial tenderness or tenderness ≤ 2.5 cm diameter or positive Carnett sign | 28 | 0.15 | 60 | 1 | 90 | 5 |

| Appendicitis6,7 | ||||||

| Fever | 1.9 | 0.58 | 9 | 3 | 39 | 16 |

| Migration of pain from the periumbilical area to the right lower quadrant of the abdomen | 3.2 | 0.5 | 14 | 3 | 52 | 14 |

| Pain before vomiting8 | 1.2 | 0.24 | 6 | 1 | 28 | 7 |

| Psoas sign | 2.4 | 0.9 | 11 | 5 | 44 | 23 |

| Rebound tenderness | 2 | 0.54 | 10 | 3 | 40 | 15 |

| Right lower quadrant pain | 7.3 to 8.5 | 0 to 0.28 | 28 | 1 | 71 | 9 |

| Right lower quadrant point tenderness (McBurney sign)9,10 | 3.4 | 0.4 | 15 | 2 | 53 | 12 |

| Rigidity | 3.8 | 0.82 | 17 | 4 | 56 | 21 |

| Rovsing sign9,10 | 2.5 | 0.7 | 12 | 4 | 45 | 19 |

| Bowel obstruction11 | ||||||

| Abdominal distention | 5.8 | 0.4 | 23 | 2 | 66 | 12 |

| Abdominal distention in combination with increased bowel sounds, vomiting, constipation, or previous abdominal surgery* | 9.2 to 13.5 | 0.5 to 0.7 | 33 | 3 | 75 | 13 |

| Colic | 2.9 | 0.8 | 13 | 4 | 49 | 20 |

| Constipation | 8.8 | 0.6 | 32 | 3 | 75 | 16 |

| Pain decreases after vomiting | 4.3 | 0.8 | 18 | 4 | 59 | 21 |

| Previous abdominal surgery12 | 3.9 | 0.2 | 17 | 1 | 57 | 6 |

| Cholecystitis | ||||||

| Murphy sign13 | 15.6 | 0.4 | 78 | 2 | > 99 | 10 |

| Right upper quadrant tenderness | 1.6 | 0.4 | 8 | 2 | 35 | 12 |

| Diverticulitis14 | ||||||

| Clinical impression of diverticulitis | 32 | 0.33 | 63 | 2 | 91 | 10 |

Factors including race, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status often influence the diagnostic evaluation. In a retrospective study examining what prompted emergency department physicians to perform computed tomography (CT) in the evaluation of acute abdominal pain, symptoms reported by Black and Hispanic patients were 26% and 56% less likely to be categorized as high acuity, and these patients were one-half as likely to have CT performed compared w ith White patients.18 Understanding health disparities is critical in preventing delayed or missed diagnoses and the inappropriate use of imaging.19

HISTORY

The patient's description of pain, location, acuity, temporal course, and previous similar episodes helps narrow the diagnosis. The pattern of pain radiation and migration over time is helpful. Abrupt or excruciating abdominal pain must be urgently considered for conditions listed in Table 3.20 Extra-abdominal conditions such as respiratory infection, testicular torsion, or systemic conditions such as diabetic ketoacidosis can also present with abdominal pain.2,20 Obtaining a menstrual history and asking about pelvic cramping, vaginal bleeding, and sexual activity are essential in patients who have female reproductive organs. The timing of the last known void may suggest urinary retention.

| Aortic dissection |

| Intra-abdominal hemorrhage |

| Ischemia of a solid or hollow organ |

| Obstruction of a biliary or ureteral duct |

| Perforation of hollow organ |

| Rupture of aortic aneurysm |

Conditions causing acute abdominal pain often have associated symptoms that help differentiate their etiologies. Nausea and vomiting are commonly associated symptoms; however, they are more likely in acute gastroenteritis, small bowel obstruction, appendicitis, and ileus. Left lower quadrant pain, anorexia, nausea without vomiting, change in bowel habits, and fever suggest diverticulitis.14,21 Acute cholecystitis can present with fever, nausea, vomiting, and, less commonly, jaundice.13 In small bowel obstruction, bloating, constipation, and obstipation are common.22 Other symptoms that can focus the evaluation include hematemesis, hematochezia, hematuria, and dysuria.

Elements of the medical, surgical, social, and family histories can provide clues to help identify the cause (e.g., nonsteroidal analgesic use should increase suspicion for gastritis or peptic ulcer disease). Previous abdominal surgery, radiation, Crohn disease, or malignancy should prompt consideration of small bowel obstruction.22,23

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

Examination of the patient with acute abdominal pain should start by rapidly assessing clinical status. Abnormal vital signs such as fever, tachycardia, and hypotension help identify patients at the highest risk. During the history and physical examination, stillness can suggest peritonitis, or writhing can suggest biliary or renal colic.20 The abdominal examination begins with an inspection followed by auscultation, percussion, and palpation. Abdominal inspection may find scars, distention, rash, or a pulsatile mass.20,22 Auscultation of high-pitched or mechanical bowel sounds may be noted with small bowel obstruction.12 Absent bowel sounds are an alarm symptom in patients with suspected mesenteric ischemia or small bowel obstruction with strangulation. A high index of suspicion is more important than examination findings in diagnosing these conditions because bowel sounds play a limited role in diagnosis.4 Focal percussion tenderness is a sensitive, less painful test for peritoneal irritation than palpation.20 Light and deep palpation beginning away from the site of described pain assesses for tenderness, masses, organomegaly, hernias, and ascites. Rebound tenderness, involuntary guarding, and pain with heel tap or cough suggest peritonitis. Adequate analgesia may facilitate the examination by enhancing patient comfort without sacrificing sensitivity.24,25 Older people, immunocompromised patients, and people with obesity often have more subtle physical presentations.4

Pain location and specific examination maneuvers help narrow the differential diagnosis. Signs of acute cholecystitis include right upper quadrant tenderness, mass, and abrupt cessation of inspiration due to pain during right upper quadrant palpation (Murphy sign). However, no single clinical finding can exclude acute cholecystitis in patients with acute right upper quadrant pain.13 In patients with left lower quadrant pain, clinical suspicion of diverticulitis has a positive predictive value of up to 65%.14,21 The Carnett sign (tenderness to palpation increases when the supine patient flexes their abdomen by raising their legs or shoulders) increases the likelihood that pain originates in the abdominal wall. The Carnett sign can diagnose chronic abdominal wall pain but is not accurate enough to exclude acute intra-abdominal pathology.5,26 A pelvic examination is essential in patients who have female reproductive organs presenting with lower abdominal pain to evaluate for adnexal masses and pelvic inflammatory disease. Classically taught examination findings, including the Rovsing sign, psoas sign, and obturator sign, have low sensitivity for appendicitis, but modestly increase the likelihood of appendicitis when present.6,7,9,10

Laboratory Testing

A complete blood count evaluates leukocytes, platelets, and indices of anemia. Abnormalities can suggest an infectious, inflammatory, or hemorrhagic process. An elevated C-reactive protein level suggests inflammation or infection and may help assess condition severity.12,20,27 Neither white blood cell nor C-reactive protein tests are diagnostic because no level can reliably confirm or exclude appendicitis.28 In the appropriate clinical context, lipase levels greater than three times the upper limit of normal suggest pancreatitis, but the condition is possible with a normal lipase level.20,29,30 Hepatobiliary markers such as transaminase, bilirubin, lactate dehydrogenase, and alkaline phosphatase levels help identify hepatic or ischemic disease processes. Blood urea nitrogen and creatinine values suggest prerenal, intrarenal, or postrenal etiologies of acute kidney injury. Urinalysis findings may indicate urinary tract infection or urolithiasis. The absence of hematuria does not exclude urolithiasis because 16% of patients with a confirmed diagnosis do not have microscopic hematuria.31 Strained urine collects stones for subsequent analysis. In patients with suspected sepsis or mesenteric ischemia, serum lactate should be checked even though the level may be normal in early sepsis.20

Imaging

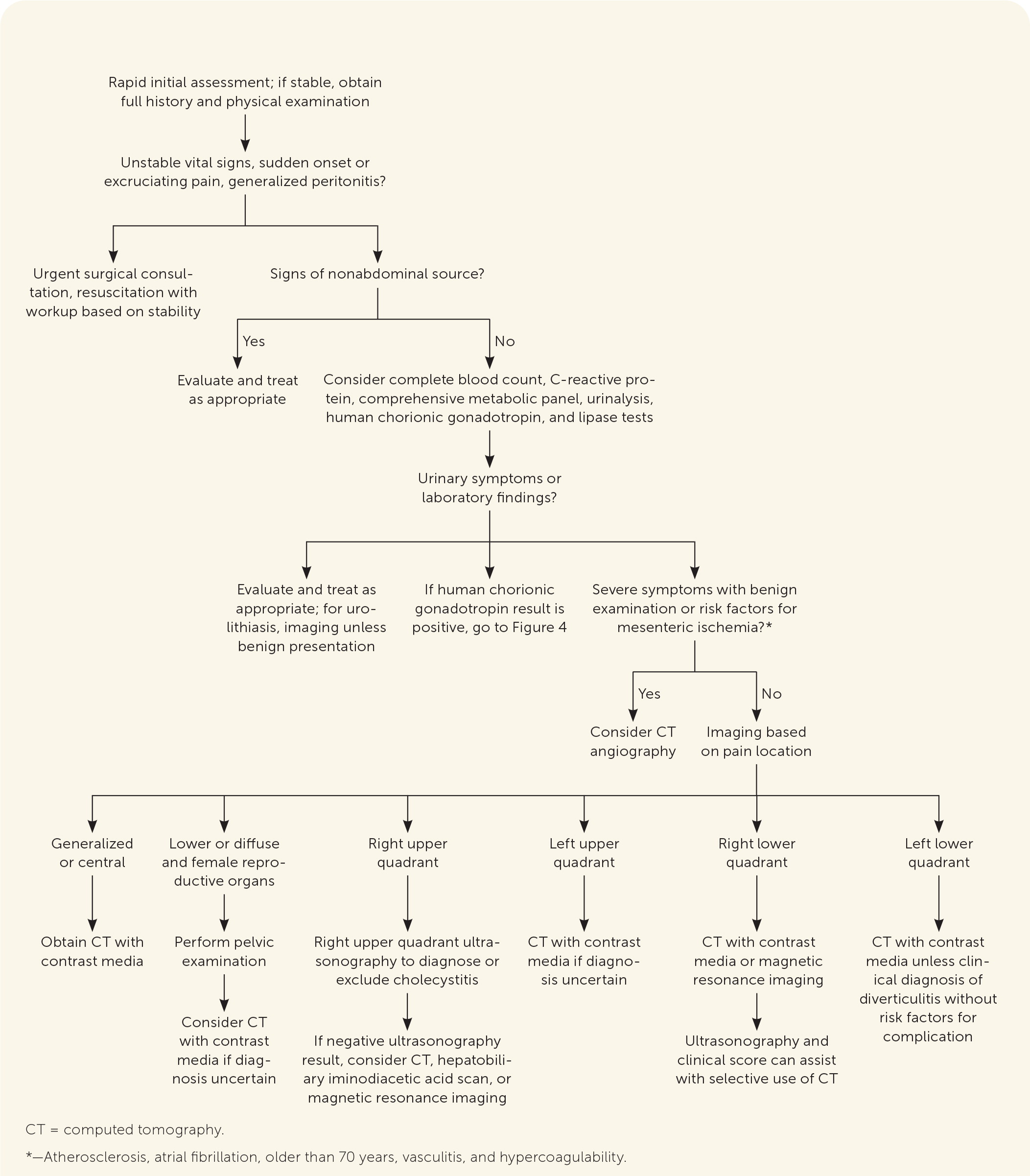

Imaging is needed in many presentations of acute abdominal pain. Clinical judgment, patient demographics, pain location, institutional protocols, and service availability affect the choice of imaging. The American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria are expert guidelines based on current evidence to help guide imaging choice.32 CT and ultrasonography have supplanted the routine use of plain radiography; however, plain radiography has a role in resource-limited settings when perforation, small bowel obstruction, or foreign bodies are suspected.20 The benefits of ultrasonography include rapid assessment and lack of radiation. Potential limitations include operator skill level, patient body habitus, bowel gas, and discomfort during scanning. Table 4 lists imaging choices by pain location.33–39 Table 5 lists clinical conditions potentially detectable by point-of-care ultrasonography (POCUS) by pain location.40–46 Figure 1 provides a diagnostic approach to acute abdominal pain in the nonpregnant adult.4,12,13,20,41,43,47–53

| Location of pain | Clinical conditions |

|---|---|

| Epigastric | Aortic aneurysm,40 cholecystitis,41,42 cholelithiasis, pericarditis40 |

| Flank, pelvic | Ectopic pregnancy,40 nephrolithiasis43 |

| Generalized | Aortic aneurysm,40 perforation40 |

| Left lower quadrant | Appendicitis,44 diverticulitis,45,46 ectopic pregnancy,40 urolithiasis43 |

| Left upper quadrant | Nephrolithiasis,43 pericarditis,40 pneumonia40 |

| Periumbilical | Aortic aneurysm,40 early appendicitis44 |

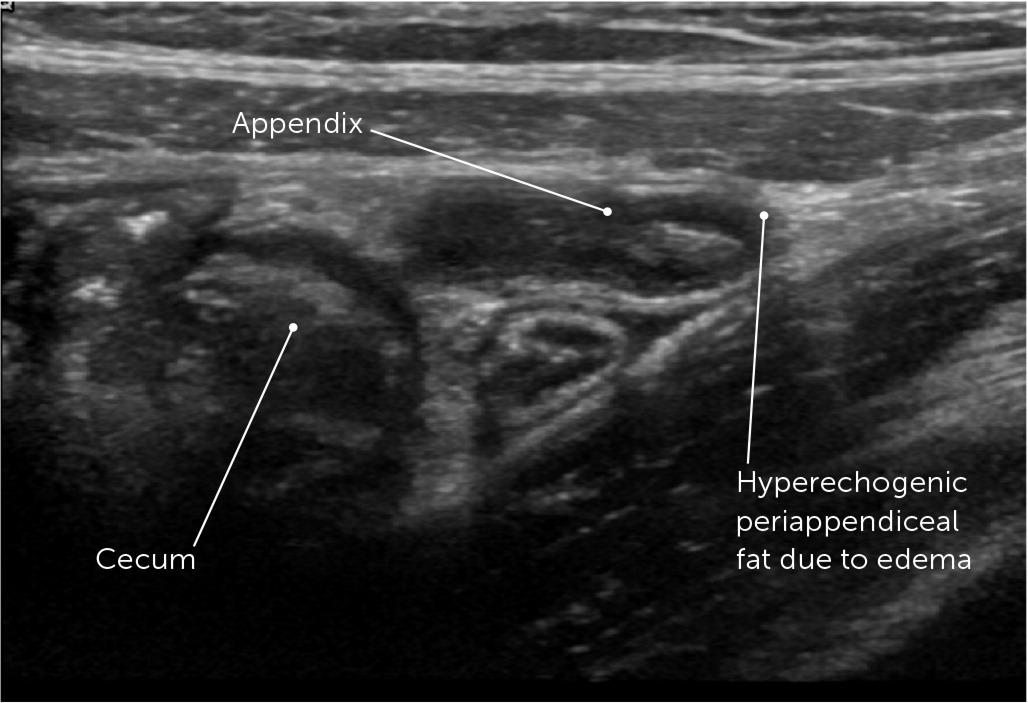

| Right lower quadrant | Appendicitis44 (Figure 3), diverticulitis,45,46 ectopic pregnancy,40 urolithiasis43 |

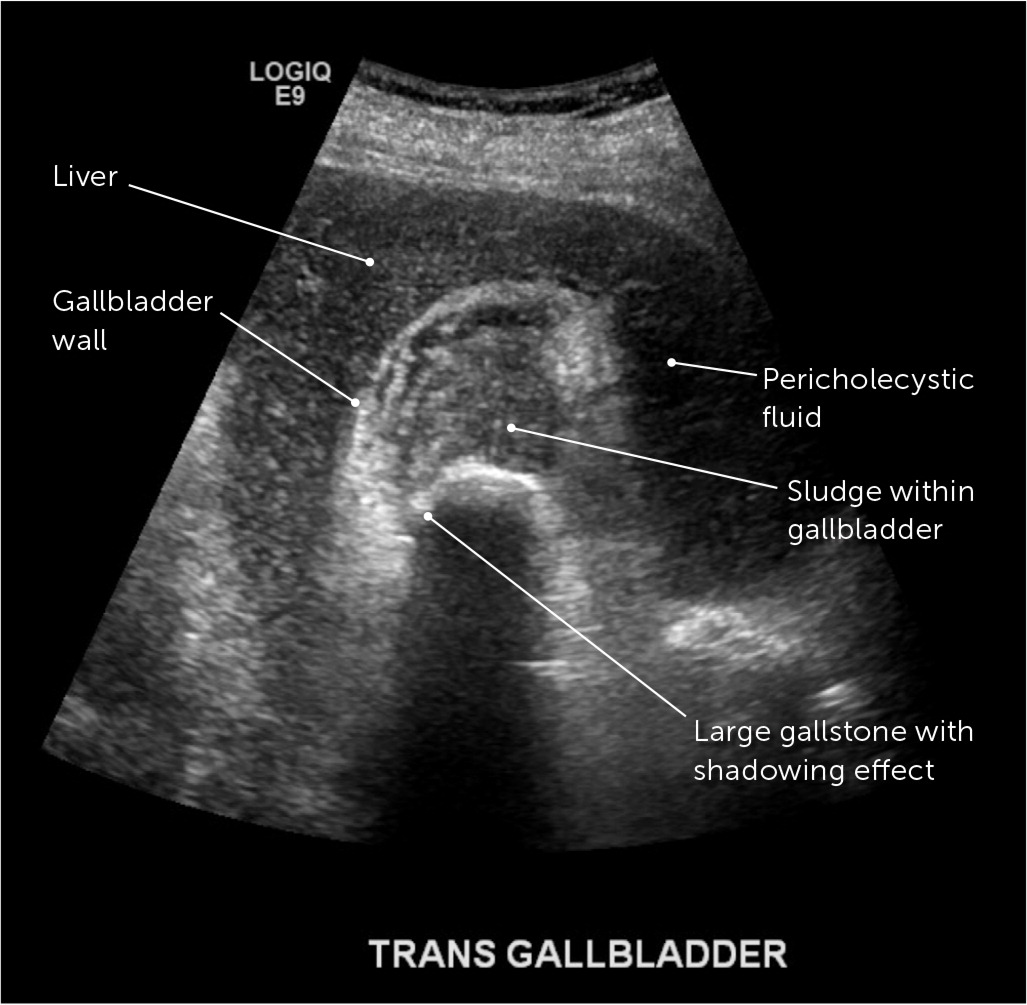

| Right upper quadrant | Appendicitis,44 pneumonia,40 cholecystitis41,42 (Figure 2), cholelithiasis, diverticulitis,45,46 nephrolithiasis43 |

| Suprapubic, lower abdomen | Appendicitis,44 distended bladder, diverticulitis,45,46 ectopic pregnancy,40 urolithiasis43 |

Nonpregnant patients with nonlocalized acute abdominal pain usually warrant an abdominopelvic CT with intravenous contrast media, especially if fever or neutropenia is present because these may suggest abscess, atypical infection, or tumor.36

Ultrasonography is the first choice for evaluation of patients with right upper quadrant pain.37,38 Because of the limitations of individual clinical findings to diagnose cholecystitis, a clinical score incorporating history, examination, and ultrasonography findings improves diagnostic accuracy and may expedite management.41,42 Table 6 lists diagnostic scores for the evaluation of adults.41,42,52 Figure 2 shows ultrasonography findings in cholecystitis. Hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scanning or CT can confirm the diagnosis when ultrasonography is equivocal.13,54,55

| Condition | Clinical score | Criteria | Points | Score value | Positive likelihood ratio | Negative likelihood ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cholecystitis | Bedside acute cholecystitis score41,42 | Postprandial symptoms Right upper quadrant tenderness | 1 1 | Radiographic ultrasonography | ≥ 4 ≥ 6 | 6.1 14.3 | 0.08 0.37 |

| Murphy sign (clinical or sonographic) Ultrasonography findings: Gallbladder wall thickening (> 3 mm) Visible gallstones | 2 2 3 | Point-of-care ultrasonography | ≥ 2 ≥ 4 ≥ 7 | 1.5 2.7 10 | Uncertain* 0.16 0.58 | ||

| Urolithiasis | CHOKAI score52 | Nausea or vomiting Hydronephrosis on ultrasonography Microscopic hematuria Prior urolithiasis Assigned male at birth Age < 60 years Pain for < 6 hours | 1 4 3 1 1 1 2 | ≥ 6 | 9.3 | 0.08 |

In left upper quadrant pain, CT with intravenous contrast media is the test of choice if the diagnosis is uncertain.35 In a study of consecutive patients in the emergency department with left upper quadrant pain, CT was nondiagnostic in 73% of cases, with the most common discharge diagnoses after nonspecific abdominal pain (61%) being urolithiasis (5%) and gastritis/gastric ulcer (5%).35

Diverticulitis is a leading diagnosis in patients with acute left lower quadrant pain, especially in patients older than 65 years.2 A clinical diagnosis of diverticulitis is reasonable for patients who are immunocompetent without risk factors for complicated diverticulitis.21,47,56 The American College of Physicians recommends imaging in patients with diagnostic uncertainty or risk factors for complicated diverticulitis.47 These risk factors include symptoms for more than five days, signs of peritonitis or obstruction, rectal bleeding, history of multiple occurrences, and immunocompromise.21,47 CT is the modality of choice.21,34 POCUS can identify uncomplicated diverticulitis and patients who require additional imaging.45,56

In patients with right lower quadrant pain, abdominopelvic CT with intravenous contrast media is the most accurate stand-alone test and the current standard of care in the United States.9,33 Routine ultrasonography and selective CT,57,58 routine ultrasonography with selective CT or clinical score–guided observation,48,59,60 and POCUS with selective CT are used in other countries.9,44 Clinical scoring tools studied include the Alvarado score, Appendicitis Inflammatory Response score, and the Adult Appendicitis score.48,59 A systematic review found routine ultrasonography with selective CT superior to routine CT in sensitivity and decreased radiation exposure by one-half, but with a lower specificity.58 Only CT or magnetic resonance imaging reliably identifies patients eligible for medical management of appendicitis.48 Figure 3 shows ultrasound findings in acute appendicitis.

Acute onset flank pain may indicate urolithiasis. An expert consensus panel applied systematic review findings and endorsed no imaging in patients younger than 35 years with typical symptoms, hematuria, pain relief with analgesics, and a previous stone history.43 POCUS, formal ultrasonography, or clinical scores that combine clinical, laboratory, and POCUS findings aid diagnosis in equivocal patients.43,61,62 Stone-protocol CT may be reserved for patients who are more likely to have a complicated disease (e.g., patients older than 50 years without a previous stone history; age older than 75 years; those with intractable pain, abdominal tenderness, or fever).43

GYNECOLOGIC

Adnexal torsion, a gynecologic emergency, often presents with nonspecific symptoms of lower abdominal pain. Nausea, vomiting, peritoneal signs, white blood cell counts greater than 11,000 per μL (11 × 109 per L), ovarian edema, and free fluid on pelvic ultrasonography increase the likelihood of surgically confirmed adnexal torsion, with a hemorrhagic ovarian cyst being the most common alternative diagnosis.49 Pelvic inflammatory disease should be considered in patients with risk factors for sexually transmitted infections and symptoms of lower abdominal pain, vaginal discharge, and adnexal or cervical motion tenderness.

PREGNANCY

A pregnancy test should be performed in all premenopausal women with acute abdominal pain, including patients using a reliable form of contraception. If positive, pelvic ultrasonography should be performed to determine the pregnancy location. If an intrauterine or ectopic pregnancy is not confirmed by transvaginal ultrasonography, ectopic pregnancy cannot be excluded, and pregnancy of unknown location is diagnosed. Determining the etiology of pregnancy of unknown location typically requires serial ultrasonography and human chorionic gonadotropin levels. The risk of ectopic rupture in patients followed for pregnancy of unknown location is as low as 0.03%.63 The M6 model, which uses immediate human chorionic gonadotropin and progesterone levels followed by repeat human chorionic gonadotropin testing at 48 hours, can predict with 96% sensitivity if a pregnancy of unknown location is a failed, intrauterine, or ectopic pregnancy.64 Heterotopic pregnancy, a co-occurring intrauterine and ectopic pregnancy, is rare, occurring in 1 in 4,000 to 1 in 30,000 naturally achieved pregnancies, but affects as many as 1 in 100 pregnancies achieved through in vitro fertilization.63

When appendicitis is suspected during pregnancy, ultrasonography is the initial imaging modality. Ultrasonography has a sensitivity of 78% and specificity of 75% for acute appendicitis but lower sensitivity in the third trimester.65 Magnetic resonance imaging has a sensitivity of 92% and specificity of 98% for acute appendicitis in pregnancy and should be considered when ultrasonography findings are inconclusive.66–68 If magnetic resonance imaging is unavailable, CT is recommended, even in early pregnancy, because CT radiation exposure is typically lower than levels associated with congenital malformations.67 Fetuses exposed to CT have low, dose-related increased rates of childhood cancer.57 Figure 4 describes an approach to the diagnosis of acute abdominal pain in pregnancy.3,64

OLDER PATIENTS

Older patients with abdominal pain are less likely to be diagnosed with nonspecific abdominal pain and more likely to be diagnosed with systemic illnesses, including diverticulitis, cholelithiasis, mesenteric ischemia, and urinary retention.2,69 Patients older than 65 years with peritonitis are one-half as likely to manifest the characteristic signs of rebound tenderness or guarding.69 CT may be more useful in older patients with acute abdominal pain because one large retrospective analysis showed that imaging changes treatment plans more than 65% of the time.70 Acute mesenteric ischemia, which commonly presents with severe pain and an unrevealing examination, is also more common in older patients. The higher rates of atherosclerosis and atrial fibrillation in older patients are risk factors because approximately 50% of acute mesenteric ischemia events are caused by emboli.50 If mesenteric ischemia is suspected, CT angiography is indicated, even in patients with renal insufficiency, because delayed or missed diagnosis is more detrimental than intravenous contrast media exposure.50,51

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Cartwright and Knudson,3 and Lyon and Clark.71

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed using medical subject headings and the key words abdominal pain, acute, adult, aging, women, developmental disabilities, and special populations limited to English and human between January 1, 2000, and February 1, 2022. Most of the retrieved studies used self-identified race and gender categories but were not always explicit about the method. PubMed was also searched using the previous terms and was limited to guidelines. Relevant citing and referenced articles were reviewed. Also searched were the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Effective Healthcare Reports, the Cochrane database, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, and Essential Evidence Plus. Search dates: February 1, 2022, and March 28, 2023.

We acknowledge Ann Emmel for her literature searches, and Dan Sutton, MD; David Baumann, MD; Ben Jarman, MD; Jody Riherd, MD; and Ron Dommermuth, MD, for their reviews of the manuscript.