This is a corrected version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(6):597-603

Patient information: See related handout on growth faltering.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Growth faltering, previously known as failure to thrive, is a broad term describing children who do not reach their expected weight, length, or body mass index for age. Growth is assessed with standardized World Health Organization charts for children younger than two years and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention charts for children two years and older. Traditional criteria for growth faltering can be imprecise and difficult to track over time; therefore, use of anthropometric z scores are now recommended. These scores can be calculated with a single set of measurements to assess malnutrition severity. Inadequate caloric intake, the most common cause of growth faltering, is identified with a detailed feeding history and physical examination. Diagnostic testing is reserved for those who have severe malnutrition or symptoms concerning for high-risk conditions, or if initial treatment fails. In older children or those with comorbidities, it is important to screen for underlying eating disorders (e.g., avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, anorexia nervosa, bulimia). Growth faltering can usually be managed by the primary care physician. If comorbid disease is identified, a multidisciplinary team (e.g., nutritionist, psychologist, pediatric subspecialists) may be beneficial. Failure to recognize and treat growth faltering in the first two years of life may result in decreased adult height and cognitive potential.

Growth faltering, previously known as failure to thrive, is a broad term used to describe children who fall below their anticipated growth trajectory due to malnutrition.1 Use of the term growth faltering is increasing as a more descriptive and less distressing diagnosis.1,2 Growth faltering affects up to 1 in 10 children and is more common in families of low socioeconomic status, children of refugees, and children with developmental delay.2 Additional risk factors include low birth weight, fetal growth restriction, gastrointestinal disorders, congenital disorders, and infections (e.g., HIV, tuberculosis).1 Growth faltering may result in loss of maximal adult height and cognitive potential if not addressed during the first two years of life.3,4

| Inadequate caloric intake |

| Cleft lip or palate |

| Cultural or religious food restrictions |

| Eating disorders |

| Improperly prepared formula |

| Low supply of breast milk |

| Neglect or abuse |

| Poor latch (e.g., from tongue- or lip-tie) |

| Poor motor coordination (often due to Down syndrome or neuromuscular disorders) |

| Gastroesophageal reflux |

| Gastrointestinal pain (e.g., due to porphyria or constipation) |

| Inadequate absorption of nutrients |

| Celiac disease |

| Congenital disorders of the gastrointestinal tract (e.g., biliary atresia, pyloric stenosis, tracheoesophageal fistula) |

| Inborn errors of metabolism |

| Infections (e.g., parasitic infection, Helicobacter pylori) |

| Inflammatory bowel disease (e.g., Crohn disease, ulcerative colitis) |

| Milk protein allergy |

| Increased metabolic demand |

| Chronic infections (e.g., HIV, tuberculosis, secondary to immunodeficiency) |

| Congenital heart disease |

| Congenital lung disease (e.g., bronchopulmonary dysplasia) |

| Cystic fibrosis |

| Hyperthyroidism |

| Malignancy |

| Renal disease |

| Thyroid disease |

Inadequate intake is most common and primarily occurs in the neonatal period.1 Causes of neonatal weight loss include improperly prepared formula, low supply of breast milk, and poor latching. For older children, causes of inadequate intake include disordered eating, avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder, pervasive refusal syndrome, or feeding disorders of attachment.8–11 Children of any age are at risk of inadequate caloric intake if they have restricted quality or quantity of food resources.8 Up to 14% of U.S. households experience food insecurity, which may only become apparent when growth faltering is diagnosed.12

Inadequate absorption of nutrients and excessive use of energy are less common but should be considered when supporting findings are identified or the child does not improve with increased caloric intake. Conditions associated with inadequate absorption of nutrients include celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, inborn errors of metabolism, milk protein allergy, and congenital changes in structure and function of the gastrointestinal tract13 Causes of growth faltering from excessive use of energy include kidney disease, malignancy, congenital heart and lung disease, and chronic infections (e.g., HIV, tuberculosis).2

Diagnosis

Growth faltering is identified using standardized growth charts from the World Health Organization (WHO) or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) based on patient age. For children younger than two years, the CDC recommends that measurements be adjusted for gestational age at birth and plotted on WHO growth charts. Screening involves careful measurements of weight and length (most accurate with patients wearing nothing or only a clean, dry diaper) and head circumference.2,14 Weight and height should be measured in children older than two years while they are wearing light clothing and no shoes. Use of CDC growth charts is recommended for patients two to 20 years of age.15 Adjusted growth charts are available for children with conditions such as cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, Turner syndrome, and cri du chat syndrome, but these are based on smaller data samples.16 corrected

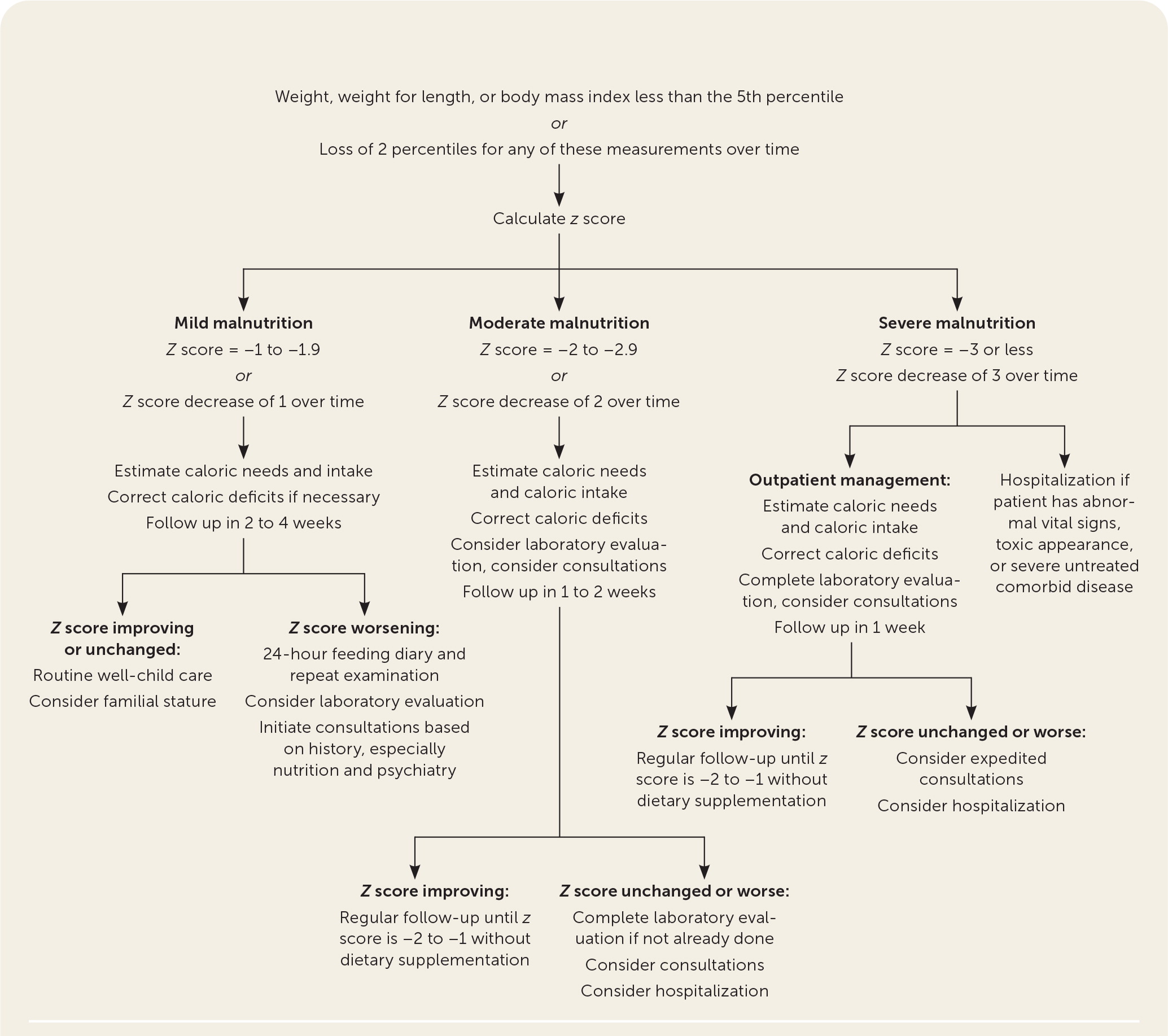

The diagnosis of growth faltering traditionally relied on poorly standardized definitions, which were based solely on growth chart percentiles.6,7 Prior criteria for growth faltering included weight, weight for length, or body mass index (BMI) measurements persistently lower than the 5th percentile or a decrease of any of these measurements by two percentile lines over time. These criteria are no longer recommended for diagnosis.7

Using anthropometric z scores simplifies diagnosis and classification of severity.2,13 Modified z scores (a statistical measurement of standard deviation from WHO and CDC) are calculated from the weight for length or BMI by age. Z scores range from −3 to +3. Negative z scores represent lower growth percentiles, with lower negative values signifying more severe malnutrition.14,16,17 Figure 1 describes how to classify severity of malnutrition using z scores.2,6 Children with z scores that decrease by 1 or more are likely to develop growth faltering, unless the decrease is compensatory for a condition such as large for gestational age at birth. Z scores enable diagnosis with a single set of measurements and better assessment of the response to treatment, especially for children in the 3rd percentile or lower on growth charts.14,16,17 Physicians can use online calculators (https://peditools.org/growthwho and https://peditools.org/growthpedi) to quickly calculate z scores in the clinical setting.18,19

Evaluation

Once the diagnosis and severity of growth faltering are established, a focused history and physical examination guide further evaluation and treatment. Obtaining a feeding history (Table 22,7) is critical for children with growth faltering. For breastfed infants, this should include duration of feedings, frequency of feedings, and concerns about milk supply or latching. For formula-fed infants, the feeding history should include the type of formula, how it is stored and mixed, and any difficulties in obtaining formula.2 For children older than six months, physicians should inquire about solid food intake, even though nutrition should mostly come from breast milk or formula until about 12 months of age.20 Families should also be asked about the child's voiding and stooling habits, and signs of feeding difficulties such as back arching, coughing, diaphoresis, or gagging.13

| What is the child being fed? Breast milk or formula Age started on whole milk Age started on solids A typical meal A typical snack Sugary drinks and snacks Vitamin supplementation How often is the child feeding? During the daytime and through the night Meals with snacks in between Symptoms after feedings? Spitting up Emesis Abdominal pain Diarrhea | How does feeding occur? Alone or while being held In a high chair Separate from the family While watching a screen Symptoms during feeds? Difficulty latching Aspiration Fatigue Dysphagia Cultural considerations? Dietary-based practices (fasting) Dietary restrictions | Are there specific food preferences? Textures Phobias Selectivity Are there additional psychosocial factors? Access to nutrition Knowledge or beliefs about food Financial resources Running water and electricity Food preparation and storage Use of supplemental nutrition programs (SNAP, WIC) Disordered eating |

A 24-hour food diary is especially important to clarify feeding history in children older than 12 months.1,2,7 Physicians should ask parents specifically about intake of juices (often of low nutritional value), frequent snacking, picky eating, and food aversions. Developmental milestones should be assessed in children 18 months or older, including use of a validated screening tool for autism spectrum disorder (e.g., Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers, Revised with Follow-Up [https://mchatscreen.com]).2,14 Children with autism spectrum disorder have a four times higher incidence of gastrointestinal symptoms and are prone to behavioral feeding difficulties that increase the risk of malnutrition.2

For adolescents, a detailed social history using the SSHADESS mnemonic (strengths, school, home, activities, drugs, emotions/eating, sexuality, safety) screens for disordered eating (i.e., anorexia nervosa, bulimia).21 In children of all ages, family participation in social programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) raises concern for food insecurity.2 Family history of gastrointestinal disease, atopy, developmental disorders, and mental health disorders can guide further evaluation.13

In children with growth faltering, the physical examination should focus on vital signs, muscle mass, fat deposition, hair thinning, and skin changes.2 Slowing of growth in head circumference may be a late finding in severe malnutrition or suggest genetic syndromes.2 Measuring midarm circumference helps assess fat deposition and can be plotted on standardized charts available from WHO (three to 23 months of age) or CDC (two to 20 years of age), which are available at https://peditools.org/whoskin and https://peditools.org/cdcmuac. These measurements are not required for diagnosis or treatment.2 Clinicians should monitor for signs of nonaccidental trauma, including burns or injuries in various stages of healing. Other concerning examination findings relevant to growth faltering include tooth decay, tonsillar enlargement, neurologic abnormalities, dysmorphisms that suggest genetic syndromes, cardiac murmur, and organomegaly.2,13 Diagnostic studies for growth faltering are not necessary initially if history and physical examination findings are normal.7

Initial Treatment

In children with mild to moderate malnutrition without signs of specific illness, nutrition interventions can be monitored in a primary care setting.2,6,13 First-line treatment includes behavioral interventions and increased caloric intake.13 If initial interventions fail, tests to consider include complete blood count, chemistry panel, celiac screening if exposed to gluten, lead level, iron studies, urinalysis, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate.2,5,8 If there is concern for aspiration or swallow dysfunction, upper gastrointestinal fluoroscopy may be helpful.2 If history suggests absorption disorders, consultation with pediatric gastroenterology for endoscopy should be considered.2 Electrocardiography, echocardiography, or genetic screening may be performed based on the evaluation findings.

Correcting a caloric deficit is usually sufficient to improve growth faltering. For newborns, initial loss of up to 10% of birth weight is expected, and 5% of breastfed infants lose more than this. Birth weight usually recovers by 14 days of life. Intervention is typically not needed unless weight loss persists beyond 21 days.1,2 For children with growth faltering, the first step in treatment is to estimate the daily calories needed for appropriate growth, which is compared with estimated current daily intake (Table 322). Estimated breast milk ingested per feeding can be calculated using the amount of milk pumped by the mother. Breast milk contains approximately 22 kcal per ounce, whereas standard formulas contain an estimated 19 to 20 kcal per ounce when mixed correctly.23,24

| Age (months) | Boys | Girls | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expected weight gain (g per day) | Estimated caloric requirements (kcal per kg per day) | Expected weight gain (g per day) | Estimated caloric requirements (kcal per kg per day) | |

| Birth to 1* | 35 | 113 | 28 | 107 |

| 1 to 3 | 29 | 104 | 24 | 101 |

| 3 to 6 | 15 | 81 | 15 | 83 |

| 6 to 9 | 10 | 79 | 9 | 78 |

| 9 to 12 | 8 | 80 | 7 | 79 |

| 12 to 18 | 9 | 82 | 9 | 80 |

| 18 to 24 | 7 | 82 | 7 | 80 |

| 24 to 36 | 4 to 10 | 84 | 4 to 10 | 81 |

If breast milk supply is insufficient for adequate growth, formula supplementation may be needed. Because the health benefits are well documented, breastfeeding should continue with formula supplementation. Lactation consultation can help mothers continue to breastfeed, but no behavioral interventions or alternate feeding techniques have high-quality evidence of increased breast milk supply or infant weight gain.20,25,26 There is no evidence that high-fat formulas improve growth over standard formulas.27 Human breast milk fortifiers are effective for low-birth-weight infants in neonatal intensive care but are unproven outside of hospitalization.28,29 In formula-fed infants, calorie-dense preparations can improve catch-up growth. Table 4 provides an example of how to mix a more concentrated formula.30–32 However, due to varying scoop sizes, it is best to consult the manufacturer's website for specific concentration recipes.7,30 Families using programs such as SNAP or WIC require physician documentation to receive additional support for the cost of formula. In older infants, breastfeeding can be supplemented with cereals or formula to stimulate growth.30 Treatment of malnutrition is critical for neurodevelopment, especially in the first two years, but the optimal pace for correction has not been established.4

| Calories (kcal) per oz | Water (oz) | Formula | Final volume (oz) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Powdered formula | |||

| 22 | 5.5 | 3 scoops | 6 |

| 24 | 5 | 3 scoops | 5.5 |

| 26 | 3 | 2 scoops | 3.5 |

| 27 | 8.5 | 6 scoops | 10 |

| Liquid formula | |||

| 22 | 13 (1 can) | 11 oz | 24 |

| 24 | 13 (1 can) | 9 oz | 22 |

| 26 | 13 (1 can) | 7 oz | 20 |

| 27 | 13 (1 can) | 6 oz | 19 |

In older children with caloric deficits, emphasis should be on a balanced diet, which includes increasing healthy fats and protein while limiting added sugars to 6 teaspoons (25 grams) or less daily.33 Appetite stimulants, such as cyproheptadine, can be beneficial for children with excessive energy metabolism (e.g., due to cystic fibrosis), but the benefits in children with general growth faltering are unclear.34

A systematic review of vitamin D supplementation in healthy and mal-nourished children showed little effect on infant or child growth when given during pregnancy or from birth until five years of age. However, vitamin D is recommended for breast-feeding infants to prevent rickets.14,35,36 Vitamin deficiencies that have been associated with malnutrition (e.g., iron, zinc) should be treated.2

Further Evaluation and Treatment

In children with severe malnutrition (z score of −3 or less) or who do not respond to initial treatment, a multidisciplinary approach (e.g., nutritionist, psychologist, pediatric subspecialists) can decrease caregiver stress and reduce severity of malnutrition, especially in children with comorbidities such as autism spectrum disorder, food avoidance, or eating disorders.2 Hospitalization is a last resort for treatment of growth faltering. Common indications for hospitalization include parental distress, outpatient treatment failure, and acute concern for the child.1–3,6,7,10,15,23 Children with severe comorbid illness and growth faltering may also require hospitalization for diagnosis or treatment of the underlying condition. Interventional strategies (e.g., nasogastric tube feeding) are reserved for patients with refractory disease or serious comorbidities.1

Children should be monitored regularly during treatment until consistent improvement in growth trajectory is demonstrated. For severe cases, close monitoring continues until the child reaches a z score of −2 to −1 without additional dietary supplementation.2 Growth is generally monitored weekly for infants one to six months of age and every other week for infants six to 12 months of age to allow sufficient time for response to treatment between measurements.1 Once growth faltering is corrected, children can return to routine growth monitoring at well-child examinations.

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Homan7; Cole and Lanham37; and Krugman and Dubowitz.38

Data Sources: A PubMed search was conducted using the key terms failure to thrive, growth faltering, and faltering growth. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. We also searched the Cochrane database and Essential Evidence Plus. In addition, references in these resources were searched and reviewed when appropriate. Search dates: March to June 2022, and April 2023.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.