Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(6):604-612

Patient information: See related handout on COPD.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) affects nearly 6% of Americans. Routine screening for COPD in asymptomatic adults is not recommended. Patients with suspected COPD should have the diagnosis confirmed with spirometry. Disease severity is based on spirometry results and symptoms. The goals of treatment are to improve quality of life, reduce exacerbations, and decrease mortality. Pulmonary rehabilitation improves lung function and increases patients' sense of control, and it is effective for improving symptoms and reducing exacerbations and hospitalizations in patients with severe disease. Initial pharmaceutical treatment is based on disease severity. For mild symptoms, initial treatment with a long-acting muscarinic antagonist is recommended. If symptoms are uncontrolled with monotherapy, dual therapy with a long-acting muscarinic antagonist/long-acting beta2 agonist combination should be initiated. Triple therapy with a long-acting muscarinic antagonist/long-acting beta2 agonist/inhaled corticosteroid combination improves symptoms and lung function more than dual therapy but increases pneumonia risk. Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors and prophylactic antibiotics can improve outcomes in some patients. Mucolytics, antitussives, and methylxanthines do not improve symptoms or outcomes. Long-term oxygen therapy improves mortality in patients with severe resting hypoxemia or with moderate resting hypoxemia and signs of tissue hypoxia. Lung volume reduction surgery reduces symptoms and improves survival in patients with severe COPD, whereas a lung transplant improves quality of life but does not improve long-term survival.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) affects nearly 6% of Americans, although state prevalence varies from 3% to 12%.1 Mortality from COPD has been slowly decreasing in men, and approximately 0.1% of men and women in the United States die from COPD.2 Globally, COPD is estimated to affect approximately 1 in 10 people.3

| A meta-analysis reviewing triple therapy with ICS/LAMA/LABA combinations showed an NNT of 16 to reduce one exacerbation in 12 months and a number needed to harm of 64 to cause one episode of pneumonia in 12 months compared with LAMA/LABA combinations. |

| A 2020 Cochrane review found phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors modestly improve lung function and reduce symptoms and the likelihood of COPD exacerbations, with an NNT of 17 to prevent one exacerbation over 39 weeks vs. placebo. |

| Prophylactic treatment with a macrolide antibiotic reduces COPD exacerbations, with an NNT of 4 to prevent one exacerbation over 50 weeks. In contrast, prophylaxis with tetracyclines and fluroquinolones demonstrates no benefit but increased harms. The long-term effect of antibiotic resistance is not known. |

| Clinical recommendations | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| A diagnosis of COPD should be confirmed with spirometry.3–6 | C | Consensus guidelines based on expert opinion |

| Physicians should avoid routine screening for COPD in asymptomatic adults.3–6,13 | C | Guidelines and consensus statements; the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force gives COPD screening a D rating |

| LAMAs should be used as the initial treatment for COPD in patients with mild symptoms and few exacerbations, with LABAs as an alternative.3,4,20 | B | Consensus guidelines based on RCTs that show more benefit from LAMA than LABA monotherapy, although LAMA/LABA combinations are more effective than monotherapy |

| Long-term oxygen therapy should be offered to patients with COPD and severe resting hypoxemia.4,30,31 | B | Consensus guidelines based on a meta-analysis of five studies |

| Long-term oxygen therapy should not be used in patients with moderate resting, nocturnal, or exertional hypoxemia.4,30–32 | B | Consensus guidelines and an RCT |

| Patients with COPD should be vaccinated for influenza and pneumococcal pneumonia.35–38 | A | Cochrane reviews demonstrating reduction in pneumonia with pneumococcal vaccination, exacerbations with influenza vaccination, and a large retrospective trial demonstrating reduction in mortality with influenza vaccination |

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| For patients recently discharged from the hospital receiving supplemental home oxygen for an acute illness, do not renew the prescription without assessing the patient for ongoing hypoxemia. | American College of Chest Physicians/American Thoracic Society |

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of COPD requires spirometry showing nonreversible obstruction during exhalation, with a ratio of less than 0.7 for forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1)/forced vital capacity (FVC) after bronchodilator use.3–5 COPD is suggested when patients present with dyspnea, a chronic cough, or sputum production and a history of recurrent lower respiratory tract infections with or without exposure to risk factors.3 COPD is not diagnosed clinically, but in a patient with history and examination findings consistent with signs and symptoms of COPD, spirometry should be performed.3–6 Relying on symptoms without performing spirometry increases the risk of misdiagnosis and can lead to delayed diagnosis or treatment.7 The differential diagnosis for COPD is listed in Table 1.8

| Disease | Distinguishing features | Disease | Distinguishing features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma Bronchiectasis Chest wall disorders Congestive heart failure Cystic fibrosis Diffuse panbronchiolitis Interstitial lung disease Lung cancer Medication adverse effects | Worsens due to environmental factors; typically diagnosed in patients younger than 40 years Dilated bronchi, productive cough, purulent sputum, and recurrent respiratory infections on chest imaging Examination findings, such as kyphoscoliosis Cardiomegaly, dry nonproductive cough, history of heart disease, and reduced ejection fraction Typically diagnosed at birth with progressive symptoms since birth Immunocompromise Restrictive defect on spirometry Worsening cough with constitutional symptoms, including weight loss and night sweats Symptoms begin after introduction of causative agent (e.g., angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, amiodarone) | Mesothelioma Nontuberculous mycobacteria infection Obliterative bronchiolitis Pulmonary arterial hypertension Tracheal stenosis Tuberculosis Upper airway obstruction (tracheal tumor) Vocal cord dysfunction | Restrictive lung pattern with associated computed tomography findings and exposure to causative agent Bronchiectasis, cavities, hemoptysis, nodules on imaging, and weight loss Progressive cough and symptoms despite treatment; computed tomography demonstrating air trapping without emphysematous changes Dyspnea and fatigue, with possible signs of cor pulmonale High-pitched inspiratory sounds High risk of exposure, including occupational and travel, with radiographic findings of upper lung cavitation Hoarseness and difficulty swallowing Hoarseness, difficulty breathing, may only tolerate short distances of activity |

Although asthma typically presents before 40 years of age and worsens with environmental factors, patients may have an overlap of asthma and COPD. This is discussed in a recent American Family Physician article.9 The presence of alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency increases the risk of developing COPD, and testing should be considered in individuals diagnosed before 45 years of age or in those without a significant history of exposure to risk factors.3,4

Tobacco use is the largest risk factor for COPD, and with more pack-years, the likelihood of COPD increases. A positive likelihood ratio (LR+) of 10 or more and a negative likelihood ratio (LR–) of less than 0.1 are large and conclusive regarding the likelihood of a disease (an explanation of LRs is available at https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/journals/afp/Likelihood_Ratios.pdf). A more than 40-pack-year smoking history has a LR+ of 8.3 but a LR− of only 0.8.

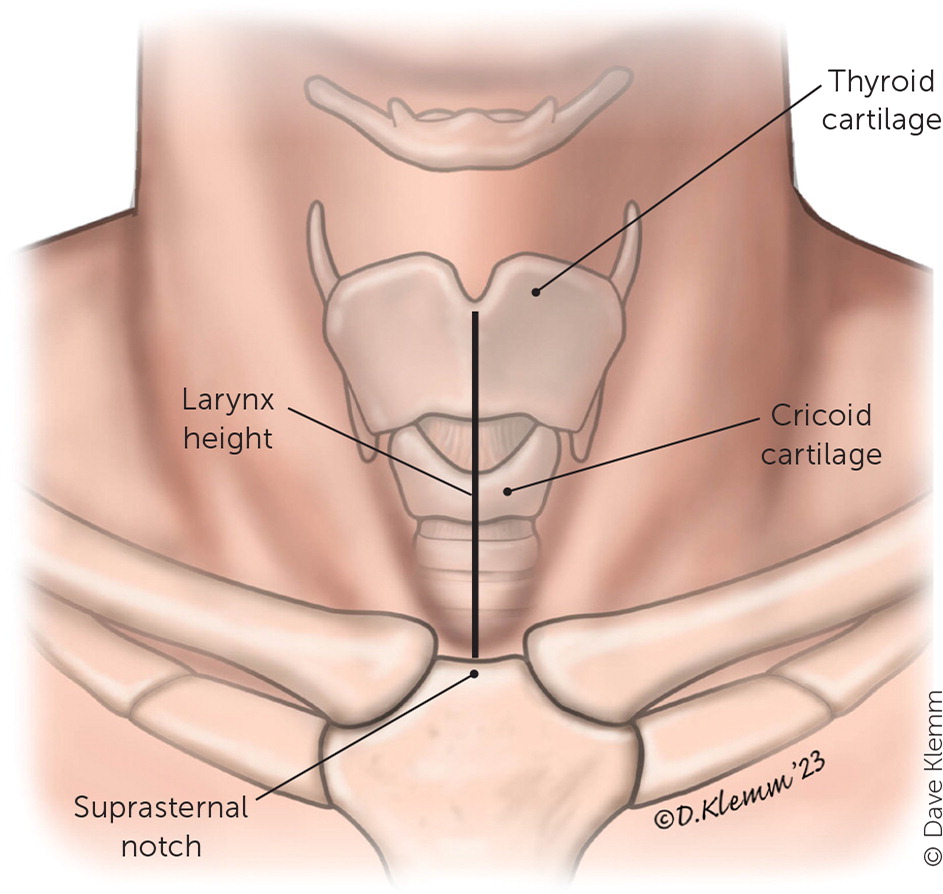

Other findings suggestive of COPD include a self-reported history of COPD (LR+ = 7.3; LR− = 0.5), maximum laryngeal height of 4 cm or less (LR+ = 2.8; LR− = 0.8), and patient age of 45 years or older (LR+ = 1.3; LR− = 0.4).10,11 A patient who has a 40-pack-year smoking history, a self-reported history of COPD, a maximum laryngeal height of 4 cm or less (Figure 1), and who is 45 years or older has a LR+ of 220 for the diagnosis of COPD.3 Examination findings, such as percussion hyperresonance, paradoxical abdominal movement, use of accessory muscles, and pursed lip breathing, are not sensitive or specific for COPD.12

Screening

Assessment of Disease Severity

Disease severity is classified based on spirometry results (Table 23) and a combined assessment of exacerbation history and symptom severity.3,6 The Modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scale or the COPD Assessment Test can be used to assess symptom severity.3 Patients are grouped based on the GOLD combined assessment (GOLD groups A, B, and E). Initial therapy is based on COPD severity, which is determined by the number of exacerbations and hospitalizations over the past 12 months and the results of a symptom assessment tool (Table 33).

| Postbronchodilator FEV1/FVC ratio | Postbronchodilator FEV1 (% of predicted) | Severity grade |

|---|---|---|

| < 0.7 | ≥ 80 | Mild |

| < 0.7 | 50 to 79 | Moderate |

| < 0.7 | 30 to 49 | Severe |

| < 0.7 | < 30 | Very severe |

| GOLD group | Classification description | Initial treatment |

|---|---|---|

| A | Zero or one moderate exacerbation per year not leading to hospital admission Modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scale score of 0 to 1 COPD Assessment Test score of < 10 | LAMAs are preferred; LABAs may be used as an alternative |

| B | Zero or one moderate exacerbation per year not leading to hospital admission Modified Medical Research Council Dyspnea Scale score of ≥ 2 COPD Assessment Test score of ≥ 10 | LAMA/LABA combination |

| E | Two or more moderate exacerbations or one or more exacerbations leading to hospitalization per year | LAMA/LABA combination; can consider LAMA/LABA/ICS combination, especially if blood eosinophils are 300 cells per μL (0.30 × 109 per L) or more |

Treatment

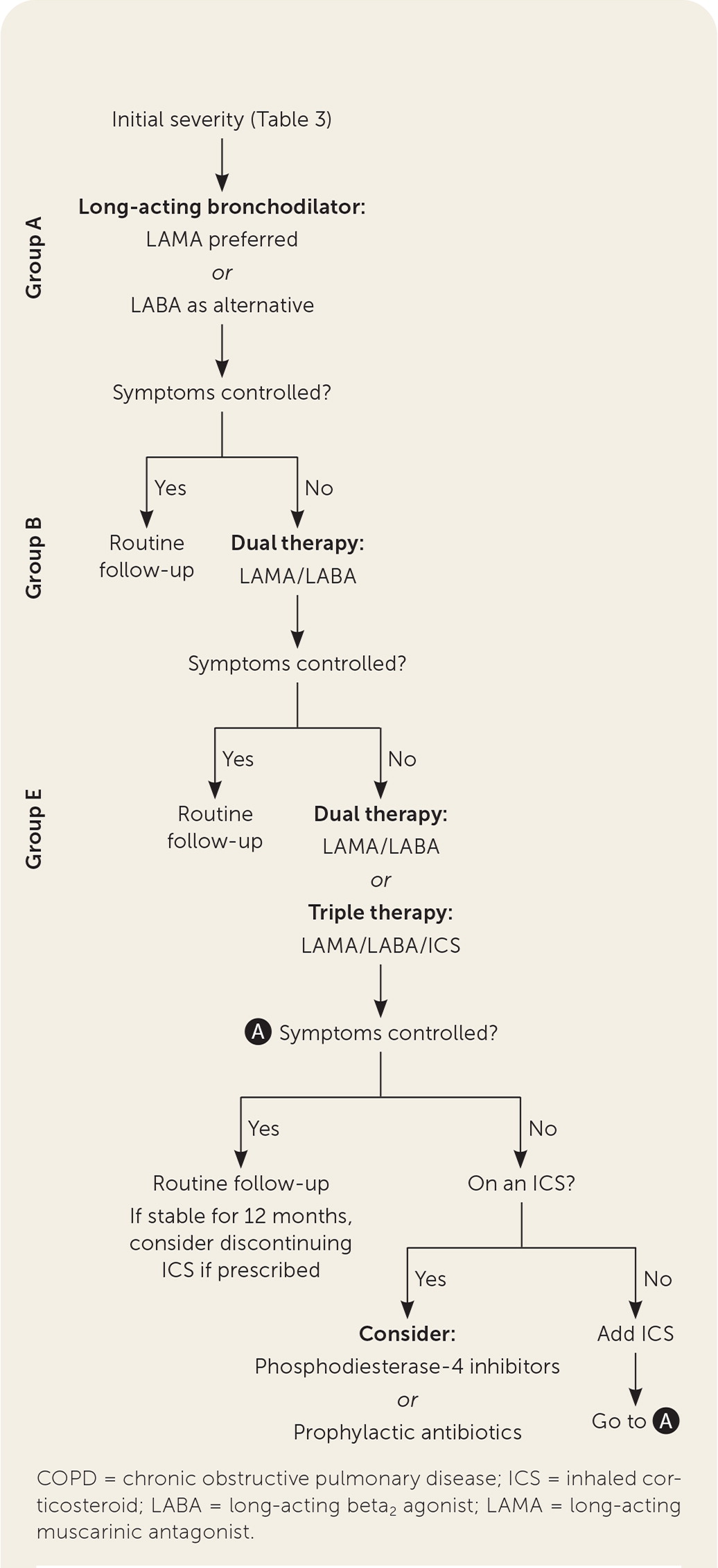

The goals of treatment are slowing progression of COPD, reducing symptoms and exacerbations, decreasing mortality, and improving quality of life. Treatment of COPD can include pulmonary rehabilitation, smoking cessation, medication, long-term oxygen therapy, and surgery. Pharmacotherapy for COPD is shown in Table 4.14 Treatment should be approached in a stepwise fashion based on symptom severity (Figure 2).

| Medication | Medication delivery | Dosage | Serious adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Short-acting muscarinic antagonist | |||

| Ipratropium (Atrovent) | Multidose inhaler | 2 puffs four times per day | Anaphylaxis, angle-closure glaucoma, hypersensitivity reaction, paradoxical bronchospasm |

| Long-acting muscarinic antagonists | |||

| Aclidinium (Tudorza) | Dry powder inhaler | 1 puff two times per day | Anaphylaxis, angle-closure glaucoma, hypersensitivity reaction, paradoxical bronchospasm |

| Glycopyrrolate (Seebri) | Dry powder inhaler | 1 puff two times per day | |

| Tiotropium (Spiriva) | Dry powder inhaler; soft mist inhaler | 2 puffs per day | |

| Umeclidinium (Incruse Ellipta) | Dry powder inhaler | 1 puff per day | |

| Short-acting beta2agonists | |||

| Albuterol | Multidose inhaler | 2 puffs every four to six hours as needed | Anaphylaxis, angina, arrhythmia, cardiac arrest, hyperglycemia, hypersensitivity reaction, hypertension, hypokalemia, hypotension, paradoxical bronchospasm |

| Levalbuterol (Xopenex) | Multidose inhaler | 2 puffs every four to six hours as needed | |

| Long-acting beta2agonists | |||

| Arformoterol (Brovana) | Nebulizer | 12 mcg every 12 hours | Angina, arrhythmia, asthma exacerbation, asthma-related death (treatment without concurrent inhaled corticosteroid), cardiac arrest, hyperglycemia, hypersensitivity reaction, hypertension, hypokalemia, hypotension, paradoxical bronchospasm U.S. Food and Drug Administration boxed warnings (salmeterol only): increased risk of asthma-related death when used as monotherapy; increased risk of asthma-related hospitalizations in children and adolescents when used as monotherapy |

| Formoterol | Nebulizer | 20 mcg every 12 hours | |

| Olodaterol (Striverdi Respimat) | Multidose inhaler | 2 puffs per day | |

| Salmeterol | Dry powder inhaler | 1 puff every 12 hours | |

| Short-acting beta2agonist/short-acting muscarinic antagonist combination | |||

| Albuterol/ipratropium | Nebulizer; soft mist inhaler | Nebulizer: 3 mL four times per day Inhaler: 1 puff four times per day | Anaphylaxis, angina, angle-closure glaucoma, arrhythmia, asthma-related death (treatment without concurrent inhaled corticosteroid), cardiac arrest, hyperglycemia, hypersensitivity reaction, hypertension, hypokalemia, hypotension, paradoxical bronchospasm |

| Long-acting beta2agonist/long-acting muscarinic antagonist combinations | |||

| Formoterol/aclidinium (Duaklir Pressair) | Dry powder inhaler | 1 puff every 12 hours | Same adverse effects as individual classes listed above |

| Formoterol/glycopyrrolate (Bevespi Aerosphere) | Multidose inhaler | 2 puffs two times per day | |

| Olodaterol/tiotropium (Stiolto Respimat) | Multidose inhaler | 2 puffs per day | |

| Vilanterol/umeclidinium (Anoro Ellipta) | Dry powder inhaler | 1 puff per day | |

| Long-acting beta2agonist/inhaled corticosteroid combinations | |||

| Formoterol/budesonide (Symbicort) | Multidose inhaler | 2 puffs two times per day | Adrenal suppression (long-term use), anaphylaxis, arrhythmia, asthma exacerbation, asthma-related death (treatment without concurrent inhaled corticosteroid), cardiac arrest, cataracts (long-term use), Churg-Strauss syndrome, eosinophilia, growth suppression (long-term use in children), hypercorticism (long-term use), hyperglycemia, hypersensitivity reaction, hypertension, hypokalemia, hypotension, immunosuppression (long-term use), open-angle glaucoma (long-term use), osteoporosis (long-term use), paradoxical bronchospasm |

| Formoterol/mometasone (Dulera) | Multidose inhaler | 2 puffs two times per day | |

| Salmeterol/fluticasone | Dry powder inhaler | 1 puff every 12 hours | |

| Vilanterol/fluticasone (Breo Ellipta) | Dry powder inhaler | 1 puff per day | |

| Triple combination therapy (inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting muscarinic antagonist/long-acting beta2agonist) | |||

| Budesonide/glycopyrrolate/formoterol (Breztri Aerosphere) | Multidose inhaler | 2 puffs two times per day | Same adverse effects as individual classes listed above |

| Vilanterol/umeclidinium/fluticasone (Trelegy Ellipta) | Dry powder inhaler | 1 puff per day | |

| Macrolide antibiotics | |||

| Azithromycin | Oral tablet | 250 mg per day or 500 mg three times per week | Arrhythmia (not shown in studies for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, although only 12-month length), diarrhea, pancreatitis, tinnitus, vertigo U.S. Food and Drug Administration boxed warning (both medications): may cause fatal arrhythmias |

| Erythromycin | Oral tablet | 500 mg two times per day | |

| Phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitor | |||

| Roflumilast (Daliresp) | Oral tablet | 500 mcg per day | Atrial fibrillation, hypersensitivity reaction, pancreatitis, renal failure, severe diarrhea, suicidality |

PULMONARY REHABILITATION

Pulmonary rehabilitation is a structured program involving multidisciplinary health care teams that provide exercise training and education, nutrition counseling, and behavioral and mental health support. A Cochrane review showed that pulmonary rehabilitation improves dyspnea, fatigue, and emotional well-being and increases the patient's sense of control over the management of their disease.15 Functional benefits of pulmonary rehabilitation showed an average increase of 44 meters in the six-minute walk test, which is considered clinically significant. Patients with high symptom burden, impaired quality of life, a recent hospitalization, or who are at high risk of exacerbations are candidates for pulmonary rehabilitation.3,16 A meta-analysis of pulmonary rehabilitation following hospital admission after a COPD exacerbation showed reduced overall mortality, hospital stay, and readmissions. Improvements in quality of life and exercise capacity are maintained for at least 12 months.17

SMOKING CESSATION

Smoking cessation is first-line treatment in patients with COPD who continue to smoke tobacco.3–5 For patients not ready to quit smoking, starting varenicline (Chantix) increases smoking cessation at six months with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 6 (95% CI, 5 to 9) compared with waiting for readiness.18 In addition to the risk of lung cancer from smoking, COPD increases lung cancer risk proportional to COPD severity.19 Current smokers who have COPD have 4.5 times the lung cancer risk of smokers without COPD.19

INHALED BRONCHODILATORS

Long-acting inhaled bronchodilators are the recommended initial treatment for COPD to reduce or prevent symptoms.3 Long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) increase health status, improve symptoms and the effectiveness of pulmonary rehabilitation, and reduce the number of exacerbations and hospitalizations.3 Long-acting beta2 agonists (LABAs) act on lung tissue for 12 to 24 hours and improve dyspnea, exacerbation rates, health status, and number of hospitalizations.3 LAMAs and LABAs do not affect mortality. LAMAs and LABAs are the initial treatments for GOLD group A patients (i.e., those with few exacerbations and mild symptoms). LAMAs are preferred over LABAs, if tolerated, due to better evidence of benefit.3,4,20 When used as combination therapy, LAMAs plus LABAs improve lung function and reduce symptoms and exacerbation rates compared with LAMA or LABA monotherapy.21 Combination therapy is recommended for patients who are classified as GOLD groups B and E.3

Short-acting bronchodilators can sometimes improve episodic dyspnea or breathlessness. Short-acting beta2 agonists and short-acting muscarinic antagonists have a duration of action of four to six hours and are not recommended for maintenance therapy if symptoms occur frequently.22

INHALED CORTICOSTEROIDS

Inhaled corticosteroids (ICS) are not recommended as monotherapy in COPD. They do not improve mortality or FEV1 and increase the risk of oropharyngeal candidiasis and pneumonia.3,20,23 In conjunction with long-acting inhaled bronchodilators, ICS triple therapy decreases COPD exacerbation frequency and improves quality of life.3,23 A meta-analysis reviewing triple therapy with ICS/LAMA/LABA combinations showed an NNT of 16 to reduce one exacerbation in 12 months and a number needed to harm (NNH) of 64 for one episode of pneumonia in 12 months compared with LAMA/LABA combinations.24 Triple therapy reduces exacerbations and improves lung function compared with ICS/LABA or LAMA/LABA combinations in patients 40 years and older with symptomatic COPD and no more than one moderate or severe exacerbation in the past year.24,25 In patients with COPD who have blood eosinophil counts of 300 cells per μL (0.30 × 109 per L) or more, adding an ICS further reduces exacerbations but also increases the risk of pneumonia. Consider discontinuing the ICS if patients have been stable for 12 months.20

PHOSPHODIESTERASE-4 INHIBITORS

Phosphodiesterase-4 (PDE-4) inhibitors reduce pulmonary inflammation by inhibiting the breakdown of intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate. Roflumilast (Daliresp), a PDE-4 inhibitor used in the treatment of COPD, reduces moderate and severe exacerbations in patients with severe to very severe COPD who have frequent exacerbations, especially those with a history of hospitalization for acute exacerbation.3 A 2020 Cochrane review found that PDE-4 inhibitors modestly improved lung function and reduced symptoms and the likelihood of COPD exacerbations with an NNT of 17 to prevent one exacerbation over 39 weeks compared with placebo.26 Most studies in the review used PDE-4 inhibitors as monotherapy in patients with symptoms of bronchitis. Although there are limited data for the use of PDE-4 inhibitors in conjunction with LAMA/LABA and LAMA/LABA/ICS combinations, they are recommended for adjunctive therapy after optimizing inhaled medications.3,4,20

PROPHYLACTIC ANTIBIOTICS

The use of prophylactic antibiotics for patients with COPD is not common but can be considered on an individual basis to reduce exacerbations.3,4,20 A Cochrane review showed that prophylactic treatment with a macrolide antibiotic reduced COPD exacerbations with an NNT of 8 to prevent one exacerbation over 50 weeks.27 Antimicrobial resistance to prophylactic antibiotics has been shown. Several studies reported resistance, but no pooled analysis has been completed to demonstrate the amount of resistance developed.27,28 The GOLD guidelines caution that macrolides may cause QTc prolongation and antibiotic resistance. Prophylaxis with tetracyclines and fluroquinolones shows no benefit and increased harms.27 Prophylactic antibiotic therapy should be reserved for patients with frequent exacerbations who have been optimized on inhaled therapies.

MUCOLYTICS AND ANTITUSSIVES

Mucolytics may reduce exacerbations by approximately one in three years of treatment. Because there are limited data, it may be difficult to identify which patients may benefit. Anti-tussives are not recommended for long-term management of COPD because there is no evidence of benefit.3

METHYLXANTHINES

Methylxanthines (e.g., theophylline) act on lung tissue through two mechanisms: as a nonselective PDE-4 inhibitor or a bronchodilator. Because of a low therapeutic ratio, low toxicity thresholds, and significant interactions with other commonly used medications, methylxanthines are not generally recommended.3,29

ORAL CORTICOSTEROIDS

Oral corticosteroids have a high adverse effect profile and are used primarily as an adjunctive treatment for acute exacerbations in hospitalized patients or those seen in the emergency department. They are not recommended for routine use in the daily management of COPD.3,4,20 Oral corticosteroids do not reduce symptoms, exacerbations, or hospitalizations but increase adverse effects with an NNH of 6.20

LONG-TERM OXYGEN THERAPY

The American Thoracic Society, U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, and U.S. Department of Defense recommend long-term oxygen therapy for patients with COPD and severe resting hypoxemia (partial pressure of oxygen of 55 mm Hg or less or oxygen saturation of 88% or less).4,30,31 Hypoxemia is measured after the patient has been breathing room air for 30 minutes at rest. Long-term oxygen therapy reduces mortality in people who meet the criteria for severe resting hypoxemia. When there are signs of tissue hypoxia, including a hematocrit level of 55% or more, cor pulmonale, or pulmonary hypertension, long-term oxygen therapy is recommended with a partial pressure of oxygen of more than 55 mm Hg or oxygen saturation of 88% or more.4,30,31 Patients should use oxygen therapy for at least 15 hours per day with a target oxygen saturation between 88% and 92%.30 Long-term oxygen therapy is not beneficial for patients with COPD and moderate resting hypoxemia without tissue hypoxemia. It does not improve outcomes or quality of life in exertional hypoxemia.4,30,31 In a limited study, nocturnal oxygen therapy did not appear to improve outcomes in patients with isolated nocturnal hypoxemia.32

Surgery

Lung volume reduction surgery is expensive and associated with high mortality; however, it may be appropriate in some cases. Patients with severe upper-lobe emphysema and low exercise capacity who underwent lung volume reduction surgery had improved survival rates compared with pharmacologic treatment after 12 months.33 Those who underwent lung volume reduction had an increased six-minute walk distance compared with the control group.33 In severe COPD, lung transplantation increases health status and lung capacity without affecting survival.34 Less invasive bronchoscopic interventions to reduce end-expiratory volume improved exercise tolerance, health status, and lung function at six to 12 months.3 Those who may benefit from lung volume reduction surgery should be referred to a pulmonologist for evaluation before surgical intervention.4

Vaccinations

In addition to routine adult vaccinations, adults 19 to 64 years of age who smoke or have COPD should receive one dose of the 15- or 20-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV15 or PCV20), and those who receive PCV15 should receive a dose of the 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccha-ride vaccine (PPSV23) at least one year later.35 Pneumococcal vaccination reduces the severity of community-acquired pneumonia and acute COPD exacerbations.36 Annual vaccination with the inactivated influenza vaccine reduces exacerbations and mortality.37,38

Prognosis

A simple tool for estimating prognosis in COPD is the BODE (body mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise) Index for COPD Survival, available at https://www.mdcalc.com/calc/3916/bode-index-copd-survival. It is recommended that those with a low body mass index be offered nutrition support.3

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Gentry and Gentry8; Lee, et al.39; Grimes, et al.40; and Hunter and King.41

Data Sources: PubMed and Cochrane databases were searched using the key terms chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, management, treatment, prognosis, LABA, LAMA, beta agonists, muscarinic, oxygen therapy, surgery, and vaccines. We also searched Essential Evidence Plus, Clinical Evidence, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence websites. Search dates: May through August 2022 and April 15, 2023.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Air Force, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, U.S. Department of Defense, or U.S. government.