Am Fam Physician. 2023;107(6):631-641

Patient information: See related handout on supraventricular tachycardia.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

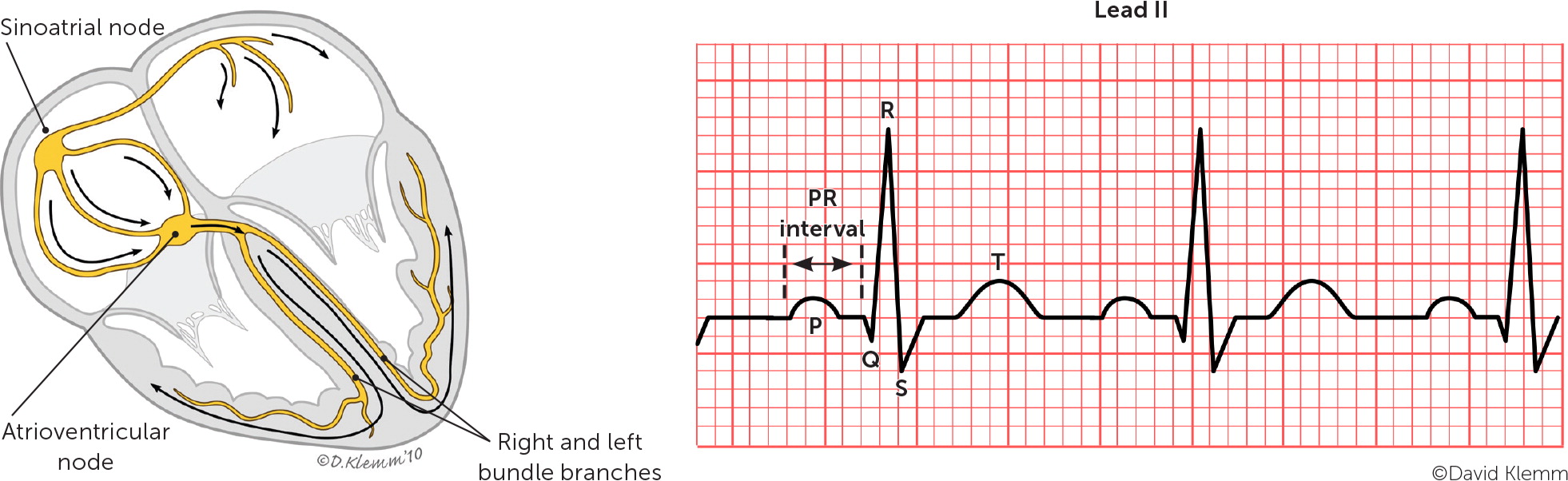

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) is an abnormal rapid cardiac rhythm that involves atrial or atrioventricular node tissue from the His bundle or above. Paroxysmal SVT, a subset of supraventricular dysrhythmias, has three common types: atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia, atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia, and atrial tachycardia. Presenting symptoms may include altered consciousness, chest pressure or discomfort, dyspnea, fatigue, lightheadedness, or palpitations. Diagnostic evaluation may be performed in the outpatient setting and includes a comprehensive history and physical examination, electrocardiography, and laboratory workup. Extended cardiac monitoring with a Holter monitor or event recorder may be needed to confirm the diagnosis. Acute management of paroxysmal SVT is similar across the various types and is best completed in the emergency department or hospital setting. In patients who are hemodynamically unstable, synchronized cardioversion is first-line management. In those who are hemodynamically stable, vagal maneuvers are first-line management, followed by stepwise medication management if ineffective. Beta blockers and/or calcium channel blockers may be used acutely or for long-term suppressive therapy. When evaluating patients for paroxysmal SVTs, clinicians should have a low threshold for referral to a cardiologist for electrophysiologic study and appropriate intervention such as ablation. Clinicians should use a patient-centered approach when formulating a long-term management plan for atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia. Catheter ablation has a high success rate and is recommended as the first-line method for long-term management of recurrent, symptomatic paroxysmal SVT, including Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome.

Supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) refers to tachycardia (i.e., atrial or ventricular rate higher than 100 beats per minute at rest) that involves tissue from the His bundle or above.1 Classically, the term paroxysmal SVT includes most tachycardias, except ventricular tachycardia and atrial fibrillation, with paroxysmal SVT comprising a subset that is characterized by a regular tachycardia having abrupt onset and termination. The prevalence of paroxysmal SVT is 2.29 per 1,000 people in the general population.1,2 Although paroxysmal SVT is a common reason for patients of all ages to visit a physician or emergency department, middle-aged women are most often affected, accounting for an estimated 62% of all cases.2,3

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Vagal maneuvers are recommended to terminate SVT in hemodynamically stable patients.1,11,15,16 | B | Consensus guidelines from the ACC and ESC; meta-analysis evaluating a modified Valsalva maneuver; Cochrane review with insufficient evidence |

| If vagal maneuvers fail, intravenous adenosine may be used in hemodynamically stable patients as a therapeutic agent in narrow complex tachycardia or as a diagnostic and therapeutic agent in undifferentiated wide complex tachycardia without preexcitation.1,11 | C | Consensus guidelines from the ACC and ESC |

| Brugada criteria can be used to distinguish between SVT with aberrant conduction and ventricular tachycardia.1 | C | Consensus guidelines from the ACC |

| Catheter ablation is generally recommended for recurrent, symptomatic SVT.1,11 | C | Consensus guidelines from the ACC and ESC |

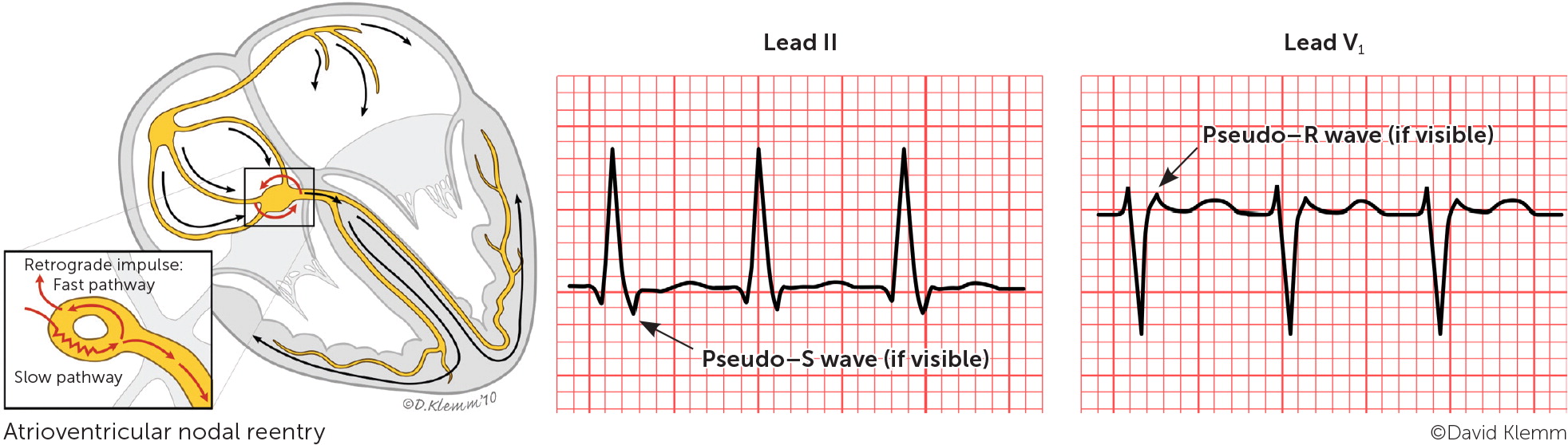

Paroxysmal SVT is classified based on the location of the reentrant circuit. The most common types are atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia, atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia, and atrial tachycardia, which are illustrated in Figure 1.4 A high index of suspicion is needed in the primary care setting because paroxysmal SVT commonly occurs without underlying cardiac disease.

Causes of Paroxysmal SVT

Paroxysmal SVT is usually not associated with structural heart disease, especially in young people. Cardiac comorbidities such as coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure, cardiomyopathy, and valvular heart disease are more common in patients with paroxysmal SVT who are older than 50 years.2 Uncommon cardiac causes include congenital/structural heart disease; myocardial scarring from diseases such as sarcoidosis and tuberculosis; prior atrial surgeries; primary electrical disorders such as long QT syndrome; and presence of accessory pathways, including familial preexcitation syndrome.2 Reentrant tachycardias can also be triggered by hyperthyroidism, electrolyte disturbances, excessive intake of caffeine or alcohol, and use of certain medications or recreational drugs. Possible triggers are listed in Table 1.

| Alcohol Anemia Caffeine Drugs Antipsychotics Bronchodilators Cannabinoids Catecholamines | Corticosteroids Decongestants Inotropes Loop diuretics Stimulants Vasodilators | Electrolyte abnormalities Exercise Fever (infection, sepsis) Hyperthyroidism Hypovolemia |

Types of Paroxysmal SVT

ATRIOVENTRICULAR NODAL REENTRANT TACHYCARDIA

The most common type of paroxysmal SVT is atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia, accounting for about two-thirds of all cases.5 This type can present at any age but is more common in young adults and in women.5,6 Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia is caused by a reentry circuit formed by the atrioventricular node and perinodal atrial tissue.7 It typically involves dual electrical pathways, one slow and one fast. An episode of typical atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia may be triggered by a critically timed premature atrial contraction that leads to retrograde conduction up the fast pathway from the atrioventricular node to the atria. The retrograde impulse depolarizes the atria forming a repetitive, self-propagating circuit with a rapid and regular ventricular response. Because retrograde atrial activation and antero-grade ventricular activation occur almost simultaneously, P waves are usually hidden on electrocardiography (ECG). However, if there is relatively delayed retrograde conduction, P waves may be seen as part of the terminal QRS complex (retrograde P waves) forming a pseudo–R deflection in lead V1 and a pseudo–S wave in the inferior leads.

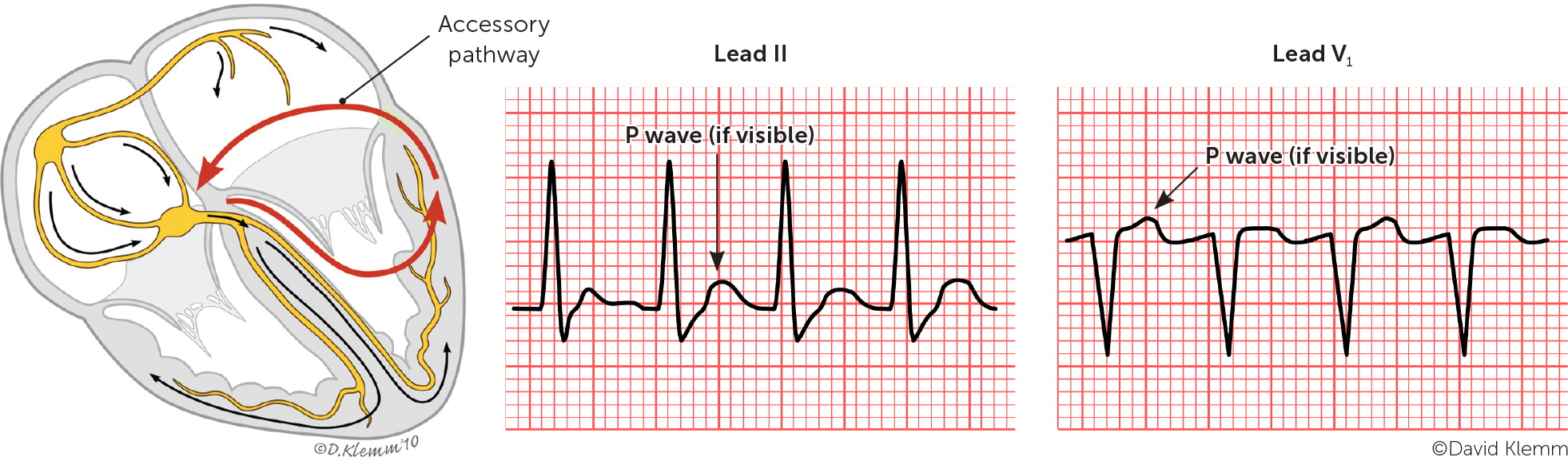

ATRIOVENTRICULAR REENTRANT TACHYCARDIA

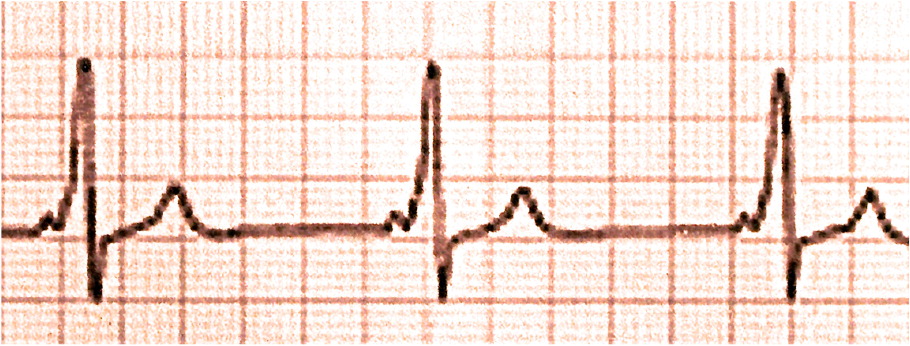

Atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia is the second most common type of paroxysmal SVT overall (approximately 30% of all cases) and the most common type in children.8 This type is a reentrant circuit tachycardia mediated by an accessory pathway. The atrioventricular accessory pathway consists of shared proximal (atrial) and distal (ventricular) tissues that form a reentrant circuit with the normal atrioventricular conduction system when triggered by a premature atrial or ventricular beat. The accessory pathway may conduct an electrical impulse in the anterograde or retrograde direction. Pathologic anterograde conduction through the accessory pathway that reaches the ventricle before the impulse through the atrioventricular node causes ventricular preexcitation. A delta wave (slurring of the QRS complex) is present on ECG in most cases of anterograde accessory tracts (Figure 23).

The combination of a delta wave, short PR interval, prolonged QRS complex, and arrhythmias involving antero-grade conduction via the accessory pathway is called Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome. The most common arrhythmias in patients with this syndrome are anterograde reciprocating tachycardia (approximately 80% of cases) and atrial fibrillation (20% to 30% of cases).9 The most serious manifestation of Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome is sudden cardiac death secondary to atrial fibrillation with pre-excitation that conducts rapidly to the ventricle over the accessory pathway resulting in ventricular fibrillation. Of note, concealed accessory pathways conduct only in the retrograde direction and therefore do not produce delta waves. Atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia can occur without the Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome pattern when the accessory pathway is retrograde and/or does not create a delta wave.

Atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia may have an orthodromic or antidromic pattern of conduction. In the orthodromic type, the impulse is conducted in the anterograde direction through the natural conduction system, depolarizing the ventricles. After conduction through the ventricles, the impulse travels in the retrograde direction through the accessory pathway to the atria, where depolarization occurs and a repetitive, self-propagating circuit with a rapid and regular ventricular response is formed. ECG typically shows a ventricular rate ranging from 150 to 250 beats per minute, a narrow QRS complex, inverted P waves, and an RP interval that is usually less than one-half of the tachycardia RR interval. In the antidromic form of atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia, premature atrial beats are blocked by the atrioventricular node but have anterograde conduction through the accessory pathway causing ventricular depolarization. After conduction through the ventricles, the impulse travels in the retrograde direction through the His bundle and atrioventricular node to the atria, completing the reentrant loop. ECG shows a ventricular rate ranging from 150 to 200 beats per minute, a wide QRS complex, inverted P waves, an RP interval that is usually more than one-half of the tachycardia RR interval, and a short PR interval.

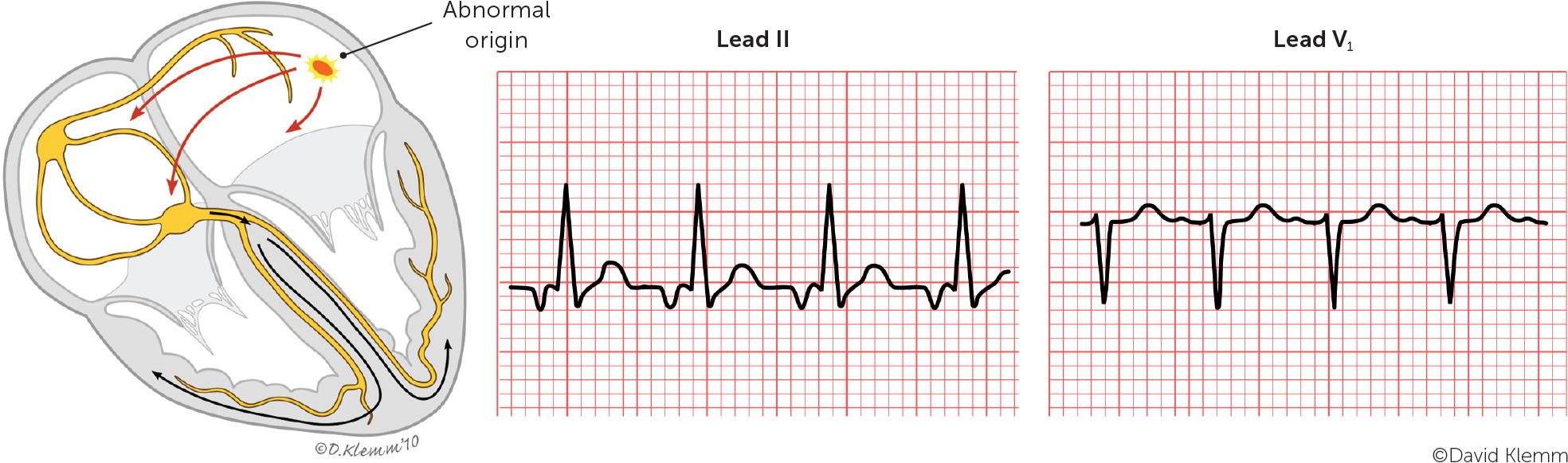

ATRIAL TACHYCARDIA

Atrial tachycardia is the least common type of paroxysmal SVT, accounting for about 10% of cases.2 It is often found in otherwise healthy young adults. Focal atrial tachycardia originates from a single site outside the sinus node within the atria and may be caused by a focal area of increased automaticity or microreentrant circuits within the atrial tissue. Focal atrial tachycardia typically presents as a regular atrial rhythm (rate greater than 100 beats per minute) with a 1: 1 ratio of atrioventricular conduction, meaning there is one atrial beat for every one ventricular beat. Atrial tachycardia due to increased automaticity often involves a warm up phenomenon in which the atrial rate abruptly increases over the first five to 10 seconds of the episode, and it may occur in repetitive, short bursts.10 In contrast, atrial tachycardia due to microreentry typically starts and stops abruptly. These characteristics may be detectable with ambulatory monitoring and can help to distinguish atrial tachycardia from sinus tachycardia, which requires a longer time to speed up and slow down. P wave morphology may differ from that in the patient's baseline ECG or may appear normal depending on the site of origin. Leads V1 and II are most useful in assessing P wave morphology. Typically, the PR interval is normal, and the RP interval is longer than the PR interval.

Evaluation

HISTORY

The clinical manifestations of paroxysmal SVT vary, and many patients are asymptomatic. Key considerations in the patient's history include a family history of the condition; the onset, duration, and frequency of symptoms; a perception of palpitations; and triggers and relieving factors.11 A variety of symptoms have been associated with paroxysmal SVT (Table 211,12) and may provide the first diagnostic clue. Table 3 includes the differential diagnosis for narrow complex tachycardia. In some patients, particularly young women, paroxysmal SVT may be misdiagnosed as panic or anxiety attacks leading to a delay in diagnosis. An underlying psychiatric history has also been associated with a delay in appropriate diagnosis of paroxysmal SVT.4,13

| Diagnosis | Rhythm | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| Atrial fibrillation | Irregularly irregular | Atrial tissue |

| Atrial flutter | Regularly irregular | Atrial tissue |

| Atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia | Regular | Perinodal atrial tissue (dual atrioventricular nodal pathways) |

| Atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia | Regular | Accessory atrioventricular conduction pathway |

| Focal atrial tachycardia | Regular | Atrial tissue |

| Inappropriate sinus tachycardia | Regular | Atrial tissue (sinoatrial node) |

| Intra-atrial reentrant tachycardia | Regular | Atrial tissue |

| Junctional ectopic tachycardia | Regular | Atrioventricular node/His bundle |

| Multifocal atrial tachycardia | Irregularly irregular | Atrial tissue |

| Nonparoxysmal junctional tachycardia | Regular | Atrioventricular node/His bundle |

| Postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome | Regular | Atrial tissue (sinoatrial node) |

| Sinoatrial nodal reentrant tachycardia | Regular | Atrial tissue (sinoatrial node) |

| Sinus tachycardia | Regular | Atrial tissue (sinoatrial node) |

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

The in-office evaluation of paroxysmal SVT should include a physical examination and ECG (Table 44), ideally completed when tachycardia is occurring.11 Additional cardiac testing can be performed if tachycardia is not occurring at the time of presentation, including transthoracic echocardiography, Holter monitor testing, wireless extended cardiac monitoring, or the rare use of an implantable loop recorder. The laboratory workup should include a complete blood count to evaluate for anemia or infection, a basic metabolic panel to evaluate for electrolyte abnormality, and thyroid function testing.11 Additional workup based on the patient's cardiac risk factors can include stress testing for cardiac ischemia or electrophysiologic studies.11 Patients found to have paroxysmal SVT should be referred to a cardiologist for confirmatory testing and treatment.

| System or test | Possible findings | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Focused physical examination | ||

| Cardiovascular | Murmur, friction rub, third heart sound | Valvular heart disease, pericarditis, heart failure |

| Respiratory | Crackles | Heart failure |

| Endocrine | Enlarged or tender thyroid gland | Hyperthyroidism, thyroiditis |

| In-office testing | ||

| Vital signs | Hemodynamic instability, fever | Induce tachycardia |

| Orthostatic blood pressure | Autonomic or dehydration issues | Induce tachycardia |

| Electrocardiography | Preexcitation | Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome |

| Wide vs. narrow QRS complex | Type of paroxysmal SVT (Figure 1) vs. ventricular tachycardia | |

| Q wave | Ischemia | |

| Other findings | Type of paroxysmal SVT (Figure 1) | |

| Laboratory testing | ||

| Complete blood count | Anemia, infection | All can cause tachyarrhythmia |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone level | Hyperthyroidism | |

| Basic metabolic panel | Electrolyte abnormality | |

| B-type natriuretic peptide level | Congestive heart failure | |

| Cardiac enzyme levels | Myocardial infarction, myocardial ischemia | |

| Additional diagnostic testing | ||

| Chest radiography | Cardiomegaly | Congestive heart failure, cardiomyopathy |

| Transthoracic echocardiography | Structural aberrations | Identify structural abnormality, baseline assessment |

| Ambulatory electrocardiography monitoring | Aberrant rhythm, frequency, duration | Type of tachyarrhythmia |

Management

SHORT-TERM OR URGENT MANAGEMENT

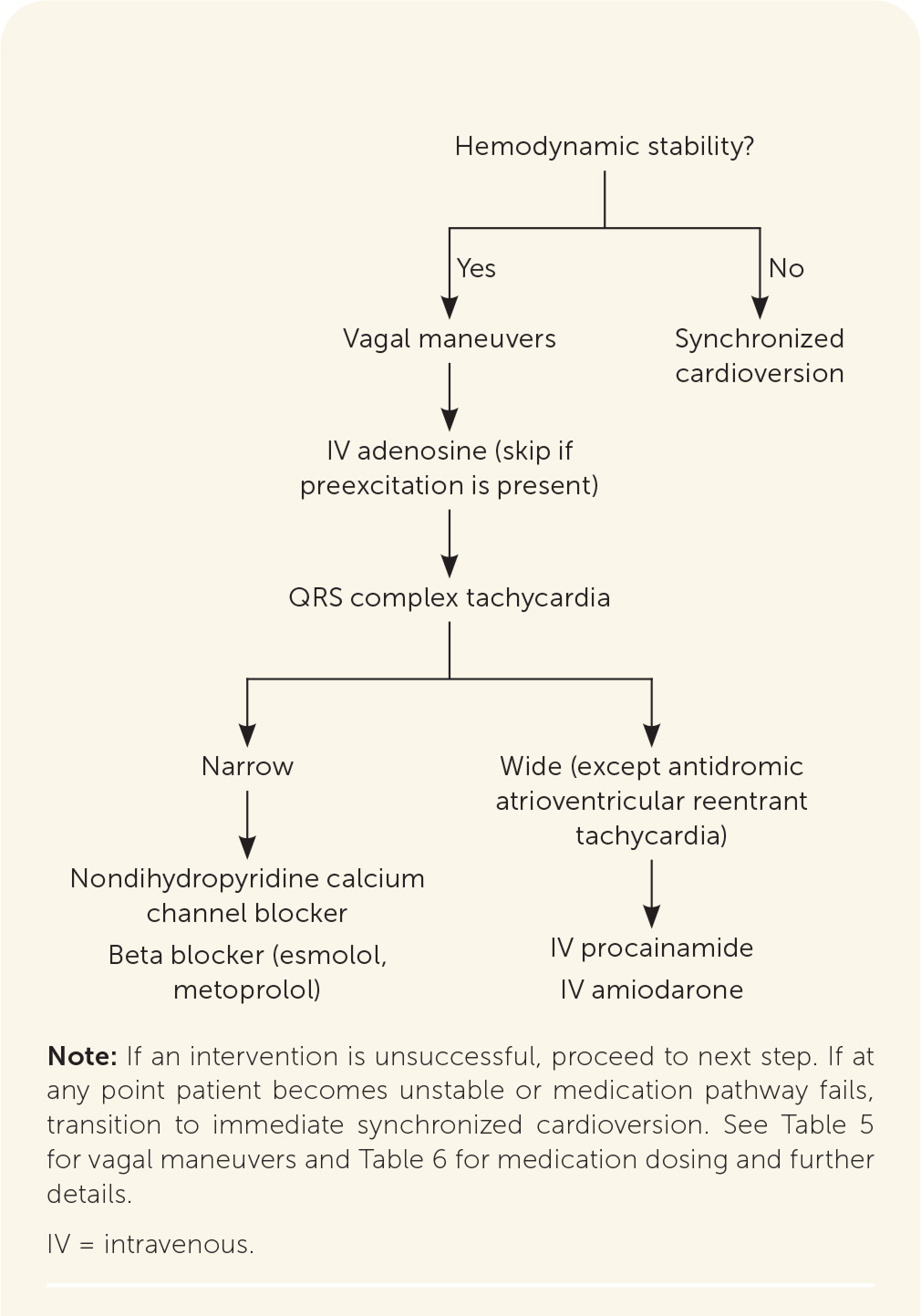

The first step in acute management of paroxysmal SVT is to determine whether it is narrow or wide QRS complex tachycardia. Acute management of narrow complex paroxysmal SVT, particularly if symptomatic, is similar across the subtypes and best initiated immediately in an emergency department or hospital setting. Synchronized cardioversion is the first-line emergent treatment in patients who are hemodynamically unstable.11 If this is unsuccessful, use of Advanced Cardiovascular Life Support pathways should be considered. Vagal maneuvers (Table 511) are first-line management for those who are hemodynamically stable, with an estimated effectiveness rate of 19% to 54%.1,11,15,16 If vagal maneuvers are unsuccessful, a stepwise approach to medication management is recommended (Figure 311 and Table 63,11,17,18).

| Carotid sinus massage (5 to 10 seconds) |

| Diving reflex (up to 30 seconds): patient submerges face in cold water or bags of ice are placed on the nose and forehead |

| Valsalva maneuvers (10 to 15 seconds): patient bears down against a closed glottis or blows through a straw or 10-mL syringe |

| Medication | Class | Characteristics | Action/uses | Dosage | Adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short-term | |||||

| Adenosine | IIe | Endogenous purine nucleotide, depresses nodal conduction | Terminates SVT, therapeutic and diagnostic in wide complex tachycardia | 6 mg IV, rapid push; can repeat with 12 mg if needed | Vasodilation leading to facial flushing, hypotension, chest discomfort, dyspnea |

| Amiodarone | IIIa | Potassium channel blocker, prolongs repolarization | May be used for a wide complex tachycardia that does not respond to adenosine | Loading dose: 150 mg IV over 10 minutes; can repeat, then 1 mg per minute for 6 hours, then 0.5 mg per minute for 18 hours; continue for a total loading dose of up to 10 g | Toxicity with long-term use |

| Diltiazem, verapamil | IVa | Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blocker, slows atrioventricular nodal conduction, negative inotrope | Decreases heart rate, terminates SVT | Diltiazem: 0.25 mg per kg IV over 2 minutes; after 15 minutes, can repeat with 0.35 mg per kg dose Verapamil: 5 to 10 mg (0.075 to 0.15 mg per kg) IV over 2 minutes; repeat with 10 mg (0.15 mg per kg) at 30 minutes after first dose | Bradycardia, hypotension, conduction disturbance, cutaneous hypersensitivity reactions, use with caution in patients with heart failure |

| Esmolol, metoprolol | IIa | Beta blocker | Decreases heart rate, terminates SVT | Esmolol: loading dose of 500 mcg per kg IV over 1 minute, then 50 mcg per kg per minute Metoprolol: 5 mg IV over 1 to 2 minutes; repeat every 5 minutes as needed to a maximum dose of 15 mg | Bradycardia, hypotension (esmolol) |

| Procainamide | Ia | Sodium channel blocker, prolongs action potential duration | Useful for wide complex tachycardia in hemodynamically stable patients | Loading dose: 10 to 17 mg per kg IV at a rate of 20 to 50 mg per minute Maintenance infusion: 1 to 4 mg IV per minute | Hypotension; avoid in patients with congestive heart failure or prolonged QT interval |

| Ibutilide | IIIa | Potassium channel blocker, prolongs repolarization | Atrial fibrillation/flutter | ≥ 60 kg: 1 mg IV over 10 minutes; may be repeated once; discontinue as soon as arrhythmia terminates | Avoid in patients with prolonged QT interval, proarrhythmic effects |

| Long-term | |||||

| Diltiazem, verapamil | IVa | Calcium channel blocker | Prevents SVT | Diltiazem: 240 to 360 mg orally per day Verapamil: 240 to 480 mg orally per day | Bradycardia, conduction disturbance, cutaneous hypersensitivity reactions, use with caution in patients with heart failure |

| Flecainide | Ic | Sodium channel blocker, slows conduction | Prevents SVT | 50 mg orally every 12 hours; increase by 50 mg twice daily at 4-day intervals to a maximum of 300 mg per day | Proarrhythmic effects, conduction disturbance, dizziness, visual disturbance, worsening of heart failure, use with caution among patients with structural or ischemic heart disease |

| Metoprolol | IIa | Beta blocker | Decreases heart rate | Immediate release (metoprolol tartrate): 25 to 200 mg orally twice per day Extended release (metoprolol succinate): 50 to 400 mg orally per day | Bradycardia, sinus pause, atrioventricular block, bronchospasm, fatigue, hypoglycemia, sexual dysfunction |

| Propafenone (Rythmol) | Ic | Sodium channel blocker, slows conduction | Prevents SVT | Immediate release: 150 mg orally every 8 hours; can be increased every 3 to 4 days to 225 to 300 mg every 8 hours Extended release: 225 mg orally every 12 hours; can be increased every 5 days to a maximum of 425 mg every 12 hours | Dizziness, nausea, unusual taste, proarrhythmic effects, hypotension; do not use in patients with ischemic or structural heart disease, wide QRS complex, or atrioventricular blocks |

If vagal maneuvers fail, intravenous adenosine may be used in hemodynamically stable patients as a therapeutic agent in narrow complex tachycardia or as a diagnostic and therapeutic agent in undifferentiated wide complex tachycardia without preexcitation.1,11 Additionally, adenosine should not be used in patients having preexcitation (a shortened PR interval with or without a delta wave), and the clinician should proceed to next steps in management,19 as outlined in Figure 3.11

All wide complex tachycardias warrant caution and should be treated as ventricular tachycardia until proven otherwise; medication management for paroxysmal SVT is potentially harmful if used in ventricular tachycardia.11,20 Brugada criteria (Table 73) can be used to distinguish between paroxysmal SVT with aberrant conduction and ventricular tachycardia.1 If a wide QRS complex tachycardia is identified in hemodynamically stable hospitalized patients, intravenous procainamide can be used as a first-line treatment. It has been shown to be more effective at terminating tachycardia within 40 minutes of use compared with intravenous amiodarone and has fewer adverse cardiac effects.11 Alternatives for short-term management of antidromic atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia include intravenous ibutilide, oral flecainide, or oral propafenone (Rythmol).11 Ultimately, if intravenous medications fail, stable paroxysmal SVT should be treated the same as if it were unstable, using synchronized cardioversion.

| Findings on electrocardiography | Criterion present? |

|---|---|

| 1. RS complex absent from all precordial leads | Yes: VT present |

| No: proceed to 2 | |

| 2. RS complex present and R to S interval > 100 milliseconds in one precordial lead | Yes: VT present |

| No: proceed to 3 | |

| 3. Atrioventricular dissociation present | Yes: VT present |

| No: proceed to 4 | |

| 4. Morphologic criteria for VT present in precordial leads V1 to V2 and V6 | Yes: VT present |

| No: supraventricular tachycardia with aberrant conduction is diagnosed by exclusion |

LONG-TERM MANAGEMENT

When evaluating a patient with known or suspected paroxysmal SVT in the outpatient setting, there should be a low threshold for referral to a cardiologist for electrophysiologic study and appropriate intervention such as ablation (Table 83). Ablation is a safe, potentially curative procedure recommended in contemporary guidelines for recurrent, symptomatic paroxysmal SVT.1,11 Not all patients should undergo electrophysiologic study and ablation, but all patients should know that there may be a curative option.

| High-risk occupation or activity (e.g., pilot, truck driver, heavy equipment operator, scuba diver, sky diver, rock climber) |

| Known structural heart disease |

| Preexcitation or delta wave |

| Symptoms not controlled with current medication management |

| Syncopal episodes |

| Uncertainty about diagnosis |

| Uncertainty about management, including consideration for ablation |

| Wide QRS complex |

Atrioventricular Nodal Reentrant Tachycardia. Clinicians should use a patient-centered approach when formulating a long-term management plan for atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia. In addition to considering patient preference, treatment decisions depend on symptom severity, frequency of the arrhythmia, medication tolerance, and comorbidity. Among patients with infrequent episodes of tachycardia and tolerable symptoms, it may be reasonable to defer ablation or long-term pharmacotherapy.11 About 50% of these patients will eventually become asymptomatic.21 Patients who decline ablation and pharmacotherapy should be educated on vagal maneuvers to terminate any recurrent arrhythmias, and treatment should be reconsidered at follow-up.

Catheter ablation is considered first-line management for symptomatic, recurrent atrioventricular nodal reentrant tachycardia.11 Ongoing pharmacologic therapy may not be needed after the procedure. For patients who are not candidates for catheter ablation or prefer not to undergo the procedure, long-term suppressive pharmacotherapy with nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers or beta blockers may be considered.11 There are limited data comparing the effectiveness of these agents; therefore, choice of agent may be determined based on patient factors such as baseline heart rate, blood pressure, and comorbidity. In patients who cannot tolerate nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers or beta blockers and do not want to pursue catheter ablation, antiarrhythmic drugs may be considered with the assistance of a cardiologist.

Atrioventricular Reentrant Tachycardia. For symptomatic, recurrent atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia, catheter ablation should be considered for first-line management.11 Patients with this finding should be referred to a cardiologist to discuss individual risks, benefits, and contraindications pertaining to the procedure. If ablation is not desirable or feasible in patients who have antidromic atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia without ischemic or structural heart disease, propafenone or flecainide may be considered for long-term treatment.11 In patients with orthodromic atrioventricular reentrant tachycardia, no signs of preexcitation on ECG, and no history of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, beta blockers or nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers may be considered.11

Patients with Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome should be referred to a cardiologist for electrophysiologic study and possible ablation. In patients with asymptomatic pre-excitation (a Wolff-Parkinson-White ECG pattern), cardiology referral can help with risk stratification, particularly in those who have high-risk occupations or are competitive athletes.11 Catheter ablation may be considered in asymptomatic patients with high-risk features identified on electrophysiologic testing.11

Focal Atrial Tachycardia. Similar to patients with the other types of paroxysmal SVTs, patients with focal atrial tachycardia who have infrequent, brief arrhythmias with minimal symptoms may not require ongoing therapy. Guidelines recommend catheter ablation for recurrent focal atrial tachycardia, especially if it is incessant or causing cardiomyopathy.11 If ablation is not desired or feasible, clinicians can consider initial pharmacotherapy with a beta blocker; a nondihydropyridine calcium channel blocker in patients who do not have reduced ejection fraction due to heart failure; or propafenone or flecainide in patients who have ischemic or structural heart disease.11

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Helton3; Colucci, et al.4; and Hebbar and Hueston.22

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms supraventricular tachycardia, treatment, and management. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Essential Evidence Plus and DynaMed were also searched. Review of literature included consensus treatment guidelines from the United States and Europe. Search Dates: May 2022 and May 2023.