Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(2):193-196

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Case Scenario 1

I am caring for F.N., a 57-year-old patient with stage IV breast cancer who is receiving chemotherapy. F.N. developed a neutropenic fever shortly after their second chemotherapy cycle and was admitted to my hospitalist service. F.N. had an absolute neutrophil count of 600 per μL (0.6 × 109 per L); after 24 hours of intravenous antibiotics, their absolute neutrophil count decreased to 400 per μL (0.4 × 109 per L). They do not want to stay in the hospital and ask to be discharged. I recommend that F.N. remains until their absolute neutrophil count reaches at least 500 per μL (0.5 × 109 per L) and blood cultures are negative after 72 hours. F.N. is genuinely appreciative of the care but states, “My days are numbered, and I want to spend as much time as I can with my family. Thank you for what you have done. I understand the risks of leaving, but I want to go home.”

Case Scenario 2

In the emergency department, I evaluate J.S., a 39-year-old man who was involved in a recreational all-terrain vehicle crash. Diagnostic trauma evaluation reveals a large (greater than 50%) right pneumothorax. He seems a little dis-oriented, and his blood alcohol level is 360 mg per dL (78.16 mmol per L; severely intoxicated). He is tachycardic and tachypneic, and his oxygen saturation is 87% on room air. When offered oxygen by nasal cannula, J.S. refuses and begins acting aggressively toward the hospital staff. When I recommend that he needs a chest tube, he refuses to give consent for the procedure and tells me that he is going to leave. J.S. has no immediate family members with him.

What is my role as a physician when a patient attempts to discharge against medical advice? What should I document if this happens? Are there circumstances in which patients should not be permitted to leave against medical advice?

Commentary

The definition of discharge against medical advice is when a patient decides to leave the hospital or other health care setting (i.e., emergency department, outpatient clinics) before the medical team recommends discharge or disposition.1 The situation occurs in multiple forms, such as patients disappearing after initial evaluation, requesting additional time to consider alternative treatment strategies, politely refusing treatment, or exhibiting hostility toward the health care team. The prevalence of discharge against medical advice is between 1% and 2% of all hospital discharges.2 Patients leaving against medical advice have a two- to fourfold higher readmission rate, increased morbidity and mortality, and are less likely to seek needed follow-up.2–5 Identified risk factors include younger age, being male, lacking medical insurance, lower socioeconomic status, substance use disorder, chronic pain, specific chronic diseases (e.g., HIV/AIDS, heart disease, pancreatitis, sickle cell disease), mental illness, and prior episodes of discharge against medical advice.6,7

How to address these situations is not routinely taught during medical education, and physicians are often distressed by the clinical and ethical challenges and the conflict with their sense of responsibility to patient safety and well-being.8 In addition, physicians may feel frustrated and believe that their clinical judgment has been challenged when patients want to leave. Patients who wish to discharge against medical advice are often labeled as nonadherent, unappreciative of care, and adding to the burdens of an already strained health care system. These situations generally result from an interplay of patient variables and/or institutional factors (e.g., patient feels better after initial treatment and underestimates the situation, including the hospital setting, its policies and staffing, or experiences dissatisfaction with care).7 Additional factors external to the medical encounter include personal, family, or work responsibilities and concern about medical expenses.

No specific guidelines exist for patients who want to leave the hospital prematurely; however, best practices include reducing potential for patient harm, determining capacity, and ensuring mutual understanding of risks and benefits. Strategies to address concern for patients wishing to discharge against medical advice must be individualized. Motivational interviewing with the patient can determine how willing they are to participate in their own care. Recommended general approaches to mitigate discharge against medical advice include treating pain and substance use withdrawal, communicating compassionately and nonjudgmentally, proactively managing concerning physical and emotional symptoms, and considering psychiatric consultation early in hostile or troubled patients.9

In addition to these preemptive measures, establishing trust is imperative. Simple efforts such as personal introductions, sitting—not standing—in front of the patient, active listening, avoiding interruptions, asking open-ended questions, and displaying empathy can help to establish mutual respect and avoid inciting or exacerbating conflict. Negotiating and compromising may allow the physician to pursue treatment while affording the patient some sense of autonomy and confidence. Involving significant family members may recruit additional encouragement and facilitate agreement to complete treatment plans. Ethics committees, psychiatry consultation, and hospital legal counsel (where available) are generally reserved for life-threatening cases. Using manipulation and threats of poor outcome, expressing frustration, and displaying anger are strongly discouraged. Physicians and medical staff must not imply that the patient's decision will result in financial penalties; this implication is false and represents financial coercion. Nevertheless, in one study, 44% of attendings and 69% of residents believed that discharge against medical advice would result in nonpayment from health insurance, and attendings who believed this were significantly more likely to convey this false statement to patients.10 A single-center retrospective study (n = 453) over a 10-year period demonstrated no cases of payment refusal based on the insured patient's decision to discharge against medical advice.10

Assessing a patient's decision-making capacity becomes critically important when the pivotal moment arrives and the patient expresses desire to discharge against medical advice. It should be noted that not all threats to discharge against medical advice are supported by equally committed intentions. One study showed that feelings of anger and anxiety in these situations can mask feelings of helplessness.11 Physicians have an ethical obligation to prove that a patient lacks capacity; this obligation can be met through a formal capacity assessment. Although many health care professionals feel inadequate and request psychiatric evaluation, these consultations often are unnecessary because the purpose of the medical capacity assessment in this context is simply to answer the question, “Should we respect the patient's wishes?”

The physician should assess the four abilities a patient must possess to provide routine informed consent. Is the patient capable of (1) understanding information about their current health condition, (2) appreciating implications of proposed treatment options, (3) exhibiting logical reasoning about these options, and (4) communicating a choice?12 If the patient still chooses to leave after capacity has been established, they should be asked to sign a waiver, and the process of discharging the patient against medical advice may proceed. Rather than considering this to be the end of the contractual relationship between the physician and the patient, the physician, with the patient's involvement, should formulate a plan to coordinate appropriate outpatient follow-up and adequate transition of care.13 Proper documentation should be recorded. Table 1 contains recommendations to consider when documenting the discharge.14

| Assess the patient |

| Assessment of decision-making capacity |

| Risks and benefits of proposed treatment |

| Investigate |

| Discussion of patient refusal and reasoning |

| Explain |

| Discussion of alternative plan with risks and benefits |

| Discharge instructions (e.g., follow-up, outpatient medications, return precautions) |

| Document |

| Medical screening examination |

| Decision-making capacity assessment |

| Efforts to negotiate and/or recruit family or friends |

| Efforts to locate if no discharge conversation occurred (e.g., emergency contacts, police, if necessary) |

Case Resolution

In Case 1, F.N. chooses to forego additional inpatient intravenous antibiotic therapy for their neutropenic fever in favor of something of greater personal value to them: spending time with loved ones at home. F.N. clearly verbalizes the risks and benefits, their reasoning is sound, and they understand how the consequences of their decision apply to their medical condition; F.N. fulfills the requirements of informed consent. A reasonable strategy to optimize care is to continue treating F.N. as an outpatient with appropriate oral antibiotics and establishing follow-up within 48 hours.

In Case 2, J.S. has several distinguishing features. First, his alcohol levels indicate severe intoxication that could incapacitate his decision-making abilities. Second, although he states that he refuses treatment, his reasoning is impaired, and his appreciation of the situation is not well-communicated. The patient's vital signs are concerning, and any further deterioration could indicate tension pneumothorax, hemodynamic instability, or other serious condition requiring life-saving treatment, even in the absence of consent. In this setting, the physician could attempt to locate a surrogate decision maker or request ethics committee consultation to determine whether involuntary detainment is necessary.

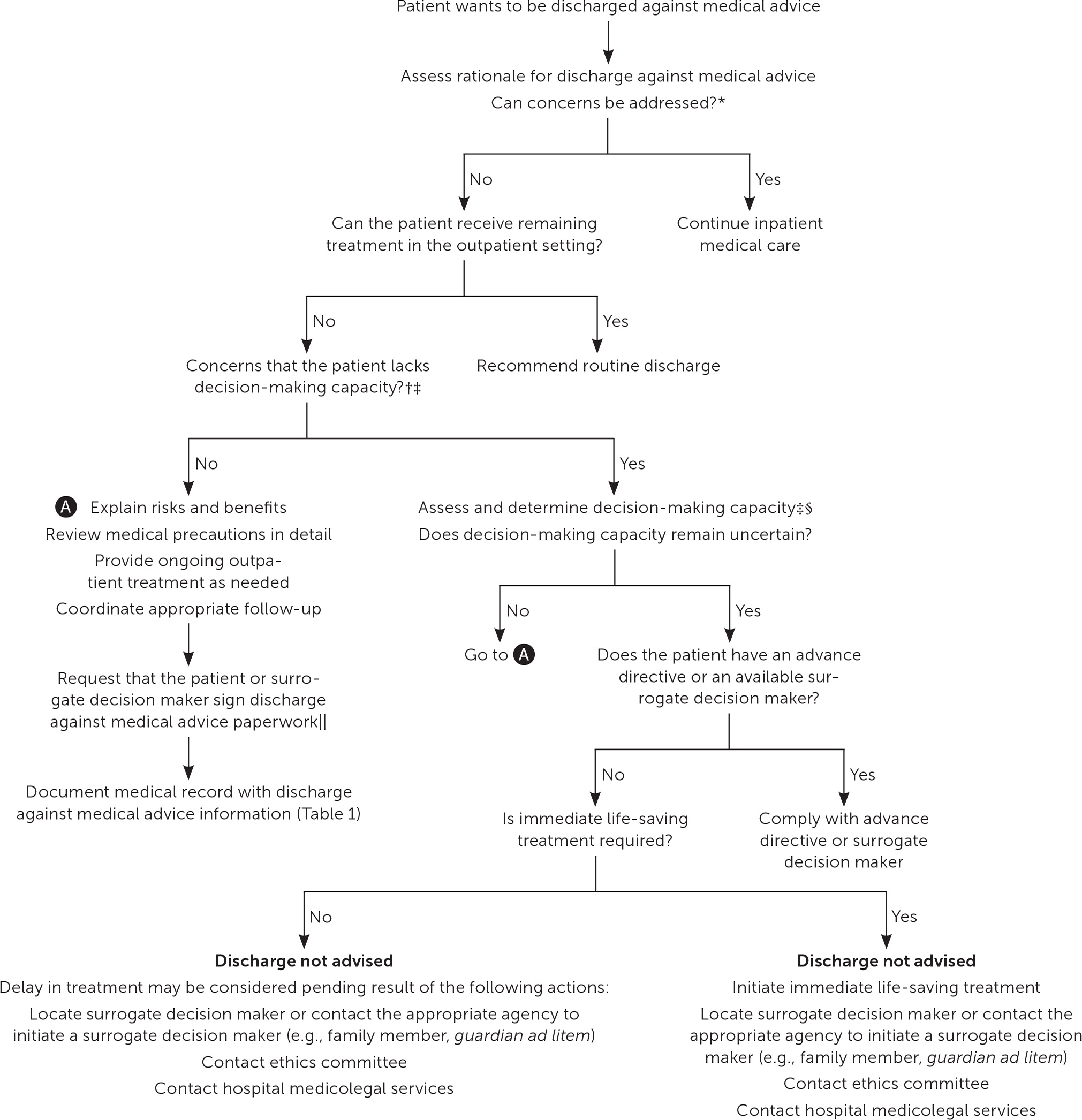

For all patients who pursue discharge against medical advice, the physician must conduct due diligence to ensure the patient has the best chances of success in choosing further treatment. Physicians should attempt to mitigate future negative encounters by anticipating greater demands from those with substance use disorder, recognizing that patients may be feeling helpless or discouraged when they initially propose to discharge against medical advice, and engaging the patient in patient-centered conversation to find the best path forward by taking the patient's values into consideration. Figure 1 provides an approach to patients wishing to discharge against medical advice.15,16

The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the U.S. Department of the Army, U.S. Department of Defense, the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, or the U.S. government.