Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(4):396-403

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Approximately 1.8 billion people will cross an international border by 2030, and 66% of travelers will develop a travel-related illness. Most travel-related illnesses are self-limiting and do not require significant intervention; others could cause significant morbidity or mortality. Physicians should begin with a thorough history and clinical examination to have the highest probability of making the correct diagnosis. Targeted questioning should focus on the type of trip taken, the travel itinerary, and a list of all geographic locations visited. Inquiries should also be made about pretravel preparations, such as chemoprophylactic medications, vaccinations, and any personal protective measures such as insect repellents or specialized clothing. Travelers visiting friends and relatives are at a higher risk of travel-related illnesses and more severe infections. The two most common vaccine-preventable illnesses in travelers are influenza and hepatitis A. Most travel-related illnesses become apparent soon after arriving at home because incubation periods are rarely longer than four to six weeks. The most common illnesses in travelers from resource-rich to resource-poor locations are travelers diarrhea and respiratory infections. Localizing symptoms such as fever with respiratory, gastrointestinal, or skin-related concerns may aid in identifying the underlying etiology.

Globally, it is estimated that 1.8 billion people will cross an international border by 2030.1 Although Europe is the most common destination, tourism is increasing in developing regions of Asia, Africa, and Latin America.2 Less than one-half of U.S. travelers seek pretravel medical advice. It is estimated that two-thirds of travelers will develop a travel-related illness; therefore, the ill returning traveler is not uncommon in primary care.3 Although most of these illnesses are minor and relatively insignificant clinically, the potential exists for serious illness. The advent of modern and interconnected travel networks means that a rare illness or nonendemic infectious disease is never more than 24 hours away.4 Travelers over the past 10 years have contributed to the increase of emerging infectious diseases such as chikungunya, Zika virus infection, COVID-19, mpox (monkeypox), and Ebola disease.3

Evaluation

Although most travel-related illnesses are self-limiting and do not require medical evaluation, others could be life-threatening.5 The challenge for the busy physician is successfully differentiating between the two. Physicians should begin with a thorough history and clinical examination to have the highest probability of making the correct diagnosis. Travelers at the highest risk are those visiting friends and relatives who stay in a country for more than 28 days or travel to Africa. Most travel-related illnesses become apparent soon after arriving home because incubation periods are rarely longer than four to six weeks.3,6 The most common illnesses in travelers from resource-rich to resource-poor locations are travelers diarrhea and respiratory infections.7,8 The incubation period of an illness relative to the onset of symptoms and the length of stay in the foreign destination can exclude infections in the differential diagnosis (eTable A).

| Tropical disease | Incubation period |

|---|---|

| Chikungunya, cutaneous larva migrans, dengue, influenza, leptospirosis, meningococcal disease, plague, travelers diarrhea, typhus, viral respiratory tract infections, yellow fever, Zika virus | < 10 days |

| African trypanosomiasis, amebiasis, babesiosis, brucellosis, hemorrhagic fever, Plasmodium falciparum, scrub typhus, tetanus, typhoid fever | 10 to 21 days |

| Filariasis, HIV, Plasmodium ovale, Plasmodium vivax, rabies, tuberculosis, viral hepatitis, visceral leishmaniasis | > 21 days |

General questions should determine the patient’s pertinent medical history, focusing on any unique factors, such as immunocompromising illnesses or underlying risk factors for a travel-related medical concern. Targeted questioning should focus on the type of trip taken and the travel itinerary that includes accommodations, recreational activities, and a list of all geographic locations visited (Table 13,6,9 and Table 23,6). Patients should be asked about any medical treatments received in a foreign country. Modern travel itineraries often require multiple stopovers, and it is not uncommon for the casual traveler to visit several locations with different geographically linked illness patterns in a single trip abroad.

| Type of travel | Key questions | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Adventure tourism | Where were the places visited (e.g., rural, urban)? What were the types of exposures (e.g., animals, water, insects)? | Adventure tourism is increasing throughout the world. Travelers may be exposed to austere environments (e.g., weather extremes) and local water or foods in more rural areas. |

| Humanitarian | Was there an illness or disease outbreak during travel? What types of medications were taken abroad? | Personal health may decline during medical missions due to difficult working conditions. Health care professionals are at risk of unique infections. |

| Mass gatherings | What were the dates and places visited? | Mass gatherings increase the risk of certain types of infections (e.g., influenza, COVID-19, measles). |

| Medical tourism | What type of procedure or medical care was provided (e.g., surgery, blood transfusions, tattoos, piercings)? | People may travel to another country for medical care or surgery. Antibiotic resistance is a global issue. Approximately 30% of international travelers return with an antimicrobial-resistant bacterium, most notably extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing bacteria, with Escherichia coli being the most common.9Travel to Southeast Asia, southern Asia, and North Africa is the biggest risk factor for acquiring an antimicrobial-resistant bacterium.9 |

| Sex tourism | Were there new sex partners while traveling? What protection was used? | Sexually transmitted infections are common among sex workers. Drug-resistant infections (e.g., gonorrhea) are increasing globally. |

| Visiting friends and relatives | What type of prophylaxis was received before travel? | Visiting friends and relatives in their home country presents unique challenges: Travelers tend to stay longer and visit more rural areas. Travelers may not think they can become ill due to living there in the past and may not have taken prophylactic medications or been vaccinated. Travelers may consume more local foods or drinks. Partial immunity to malaria decreases over time (two to three years). |

| Location | Disease |

|---|---|

| Caribbean | Acute histoplasmosis, chikungunya, dengue, leptospirosis, malaria, Zika virus |

| Central America | Chikungunya, coccidioidomycosis, dengue, enteric fever, histoplasmosis, leishmaniasis, leptospirosis, malaria (primarily Plasmodium vivax), Zika virus |

| South America | Bartonellosis, chikungunya, dengue, enteric fever, histoplasmosis, leptospirosis, malaria (primarily P. vivax), Zika virus |

| South Central Asia | Chikungunya, dengue, enteric fever, malaria (primarily nonfalciparum), scrub typhus |

| Southeast Asia | Chikungunya, dengue, leptospirosis, malaria (primarily nonfalciparum) |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | African trypanosomiasis, chikungunya, dengue, enteric fever, Katayama fever, malaria (primarily Plasmodium falciparum), meningococcal meningitis, rickettsial diseases (primary cause of fever in southern Africa) |

Travel History

Travelers visiting friends and relatives are at a higher risk of travel-related illnesses and more severe infections.10,11 These travelers rarely seek pretravel consultation, are less likely to take chemoprophylaxis, and engage in more risky travel-related behaviors such as consuming food from local sources and traveling to more remote locations.3 Overall, travelers visiting friends and relatives tend to have extended travel stays and are more likely to reside in non–climate-controlled dwellings.

During the clinical history, inquiries should be made about pretravel preparations, including chemoprophylactic medications, vaccinations, and personal protective measures such as insect repellents or specialized clothing.12,13 Accurate knowledge of previous preventive strategies allows for appropriate risk stratification by physicians. Even when used thoroughly, these measures decrease the likelihood of certain illnesses but do not exclude them.6 Adherence to dietary precautions and pretravel immunization against typhoid fever do not necessarily eliminate the risk of disease. Travelers often have no control over meals prepared in foreign food establishments, and the currently available typhoid vaccines are 60% to 80% effective.14 Although all travel-related vaccines are important, the two most common vaccine-preventable illnesses in travelers are influenza and hepatitis A.12,15

Travel duration is also an important but often overlooked component of the clinical history because the likelihood of illness increases directly with the length of stay abroad. The longer travelers stay in a non-native environment, the more likely they are to forego travel precautions and adherence to chemoprophylaxis.3 The use of personal protective measures decreases gradually with the total amount of time in the host environment.3 A thorough medical and sexual history should be obtained because data show that sexual contact during travel is common and often occurs without the use of barrier contraception.16

Clinical Assessment

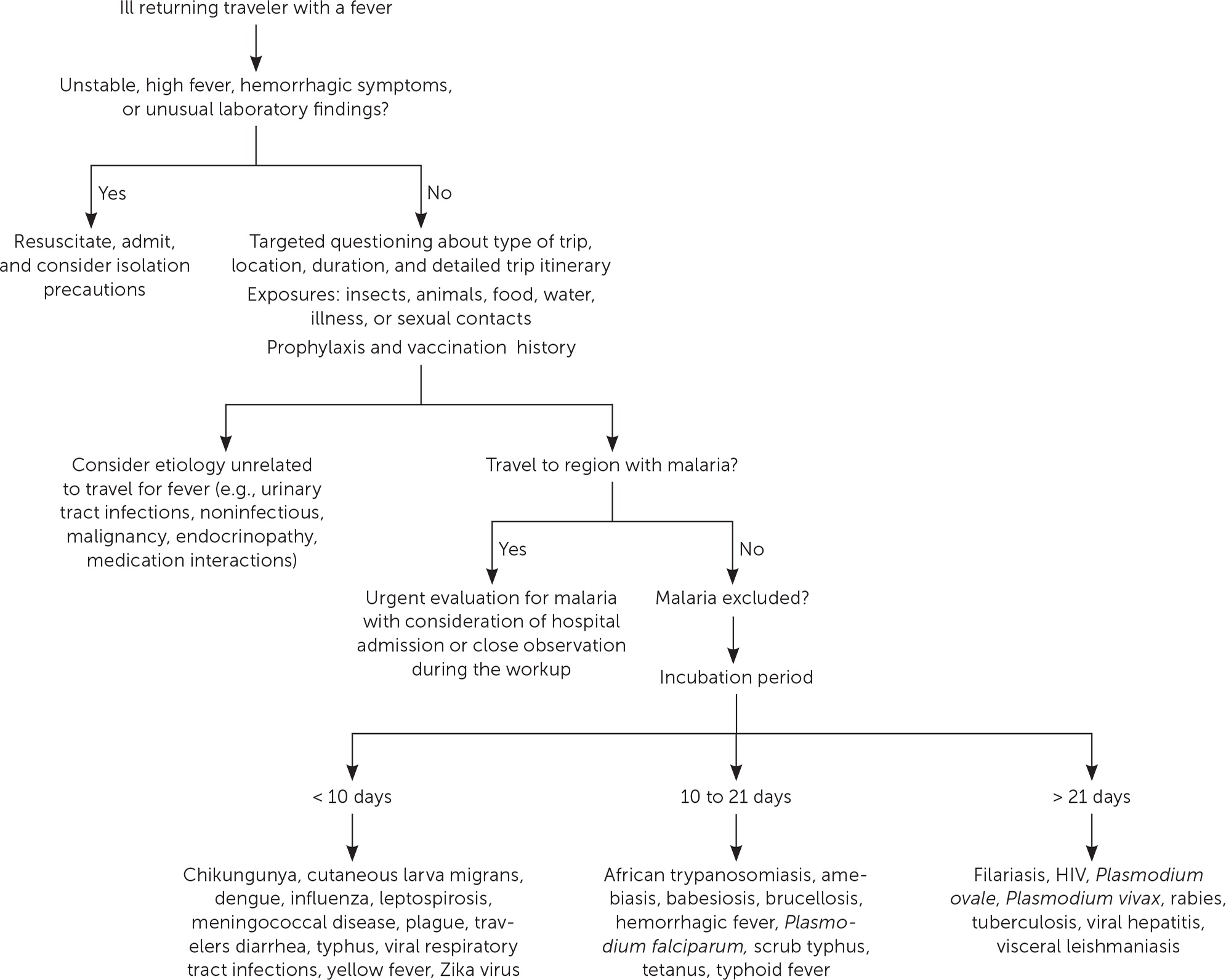

The severity of the illness helps determine if the patient should be admitted to the hospital while the evaluation is in progress.3 Patients with high fevers, hemorrhagic symptoms, or abnormal laboratory findings should be hospitalized or placed in isolation (Figure 1). For patients with a higher severity of illness, consultation with an infectious disease or tropical/travel medicine physician is advised.3 Patients with symptoms that suggest acute malaria (e.g., fever, altered mental status, chills, headaches, myalgias, malaise) should be admitted for observation while the evaluation is expeditiously completed.13

Many tools can assist physicians in making an accurate diagnosis. The GeoSentinel is a worldwide data collection network for the surveillance and research of travel-related illnesses; however, this service requires a subscription. The network can guide physicians to the most likely illness based on geographic location and top diagnoses by geography.4 For example, Plasmodium falciparum malaria is the most common serious febrile illness in travelers to sub-Saharan Africa.17

Ill returning travelers should have a laboratory evaluation performed with a complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, and C-reactive protein. Additional testing may include blood-based rapid molecular assays for malaria and arboviruses; blood, stool, and urine cultures; and thick and thin blood smears for malaria.3 Emerging polymerase chain reaction technologies are becoming widely available across the United States. Multiplex and biofilm array polymerase chain reaction platforms for bacterial, viral, and protozoal pathogens are now available at most tertiary health care centers.4 Multiplex and biofilm platforms include dedicated panels for respiratory and gastrointestinal illnesses and bloodborne pathogens. These tests allow for real-time or near real-time diagnosis of agents that were previously difficult to isolate outside of the reference laboratory setting.

Table 3 lists common tropical diseases and associated vectors.3,6,18 Physicians should be aware of unique and emerging infections, such as viral hemorrhagic fevers, COVID-19, and novel respiratory pathogens, in addition to common illnesses. Testing for infections of public health importance can be performed with assistance from local public health authorities.19 In cases of short-term travel, previously acquired non–travel-related conditions should be on any list of applicable differential diagnoses. References on infectious diseases endemic in many geographic locations are accessible online. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Travelers’ Health website provides free resources for patients and health care professionals at https://www.cdc.gov/travel.

| Type of vector or animal exposure | Associated disease | Special considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Bat | COVID-19, histoplasmosis, Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus, Nipah virus, rabies, viral hemorrhagic fevers, other emerging infections | Nearly all fatal rabies cases in the United States are due to bat bites or exposures All travelers exposed to bats should seek medical attention for possible rabies prophylaxis |

| Cat | Bartonella henselae, Capnocytophaga canimorsus, Pasteurella multocida, tetanus, toxoplasmosis | Cat bites likely to be infected due to deeper penetration and the anaerobic nature of the wound Exposure to young kittens |

| Dog | Ancylostoma (hookworm), C. canimorsus, Echinococcus (tapeworm), leptospirosis, Pasteurella, rabies, stool pathogens (Salmonella, Campylobacter, Giardia), tetanus, Toxocara canis (round worm) | Capnocytophaga bacteria cause rapid disease progression in people who are asplenic Cutaneous larva migrans (from Ancylostoma) is a common skin condition in returning travelers Most common transmission of rabies in developing countries |

| Flea | Murine typhus, rickettsial diseases, Yersinia pestis | Barrier precautions and chemical repellants used Exposure to rodents |

| Flies | African trypanosomiasis, enteric diseases acting as fomites, leishmaniasis, loiasis, onchocerciasis | Blackflies, the vector of river blindness, typically bite during the day and live near rapidly flowing water Sand flies, the vector for leishmaniases, can easily pass through holes in ordinary bed nets |

| Lice | Borrelia recurrentis, rickettsial diseases such as Rickettsia prowazekii | Exposure to homeless migrants or displaced persons |

| Livestock | Anthrax, brucellosis, Coxiella burnetii, cysticercosis, tetanus | 2% of all emergency department visits for seizures in the United States are associated with neurocysticercosis18 |

| Miscellaneous | Camels: Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus Mite: scrub typhus Rabbits: tularemia Reduviid bug: Chagas disease Reptiles: Salmonella | Chagas: an estimated 300,000 people in the United States are infected; acquired in Mexico and South America18 Exposure to reptilian pets |

| Mosquito | Chikungunya, dengue, Japanese encephalitis, malaria, West Nile virus, yellow fever, Zika virus | Barrier precautions and chemical repellants used Pretravel prophylaxis used |

| Poultry | Chlamydophila psittaci, influenza, Mycobacterium avium | Exposure to exotic birds |

| Primate | B virus, hepatitis A, mpox (monkeypox), tetanus, viral hemorrhagic fever | B virus is transmitted by Old World macaque monkeys; 70% mortality rate in humans (encephalomyelitis) if not treated |

| Rodent | Hantavirus, Lassa fever, leptospirosis, plague, pulmonary syndrome, rat-bite fever, rickettsial diseases | Exposure to rodents Exposure to rodent urine and droppings |

| Tick | African tick-bite fever, babesiosis, C. burnetii, Lyme disease, rickettsial diseases, tularemia | Barrier precautions and chemical repellants used Postbite prophylaxis used |

Febrile Illness

A fever typically accompanies serious illnesses in returning travelers. Patients with a fever should be treated as moderately ill. One barrier to an accurate and early diagnosis of travel-related infections is the nonspecific nature of the initial symptoms of illness. Often, these symptoms are vague and nonfocal. A febrile illness with a fever as the primary presenting symptom could represent a viral upper respiratory tract infection, acute influenza, or even malaria, typhoid, or dengue, which are the most life-threatening. According to GeoSentinel data, 91% of ill returning travelers with an acute, life-threatening illness present with a fever.20 All travelers who are febrile and have recently returned from a malarious area should be urgently evaluated for the disease.13,21 Travelers who have symptoms of malaria should seek medical attention, regardless of whether prophylaxis or preventive measures were used. Suspicion of P. falciparum malaria is a medical emergency.13 Clinical deterioration or death can occur in a malaria-naive patient within 24 to 36 hours.22 Dengue is an important cause of fever in travelers returning from tropical locations. An estimated 50 million to 100 million global cases of dengue are reported annually, with many more going undetected.23 eTable B lists the most common causes of fever in the returning traveler.

| Infectious disease | Geographic range | Incubation period | Clinical manifestation/diagnosis | Treatment | Special considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African sleeping sickness (Trypanosoma brucei) | Rural sub-Saharan Africa | 1 to 3 weeks | Nonspecific febrile illness with headache, myalgia, malaise Chancre at site of bite typically appears within a few days Central nervous symptoms (sleep disturbances, mental status changes) occur within a few weeks to months after infection Diagnosis via parasite identification in specimens of blood, chancre, lymph node, or cerebrospinal fluid | Suramin, melarsoprol, eflornithine are available through the CDC Physicians should contact the CDC for dosing and treatment guidance | Tsetse flies bite during the day; most U.S. cases come from visiting national parks or game reserves Fatal if not treated |

| Anthrax (Bacillus anthracis) | Global in wild and domestic herbivores | 1 to 7 days; may take up to 17 days | Cutaneous disease comprises 95% of worldwide cases Gram stain or PCR testing | Ciprofloxacin or doxycycline with the administration of anthrax antitoxins or monoclonal antibodies | Consider in travelers with unexplained fever and a new rash (painless papule that develops into black eschar in approximately 10 days) Associated with exposure to animal hides Mortality rate of naturally occurring inhaled anthrax is 30% to 45% Considered a category A bioterrorism agent |

| Brucellosis | Global | 2 to 4 weeks; may present up to 6 months after exposure | Nonspecific flulike symptoms Blood culture should be obtained; serologic testing is the most used technique | Doxycycline with rifampin for at least 6 weeks | Most common human infection is through consuming unpasteurized dairy products; may also be from hunting or exposure to livestock birth |

| Cat-scratch disease (Bartonella henselae) | Global | 1 to 3 weeks | Fever with papule at site of exposure Painful lymph nodes may develop proximal to site of injury Based on clinical history Serology can confirm the diagnosis; PCR test or culture from lymph node may help with diagnosis | Most cases are self-limiting and resolve without treatment Antibiotics may be used (e.g., tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole) | Young kittens are of particular concern |

| Chikungunya | Africa, Asia, the Americas, Pacific Islands | 3 to 7 days; may take up to 12 days | High fever (102°F [> 38.9°C]), maculopapular rash on trunk or extremities, and diffuse joint pain Diagnosis via testing for antibodies and nucleic acid amplification; confirmatory testing is available through the CDC | Supportive care with rest, fluids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs No antiviral available | Some patients may have relapse or worsening rheumatologic symptoms several months after illness resolves |

| Dengue | Global in tropical regions Outbreaks have occurred in Hawaii, Florida, Texas | 5 to 7 days | 40% to 80% of infections are asymptomatic or cause only mild flulike symptoms 5% of cases are life-threatening Diagnosis is based on the presence of 2 or more clinical features (nausea, vomiting, myalgias, positive tourniquet test, or leukopenia) and travel to an endemic region Severe dengue warning signs include abdominal pain, persistent vomiting, fluid accumulation, mucosal bleeding, lethargy, restlessness, liver enlargement, and postural hypotension Diagnosis via molecular and serologic testing Must report cases to state and public health authorities | No specific antiviral available Supportive therapy initiated quickly can decrease the risk of mortality from severe dengue to < 0.5% Avoid nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs due to anticoagulant properties | Perinatal transmission is possible, typically when mother is infected at time of birth Dengue may be spread via breastfeeding A vaccine is available but only for those who have had laboratory-confirmed dengue disease Immunization without past infection increases the risk of severe disease |

| Ebola | Sub-Saharan Africa | 2 to 21 days | Nonspecific fever, headache, arthralgia; late stages include multiorgan failure and hemorrhage Diagnosis via antigen detection assays, PCR, or direct virus isolation | Isolation and supportive care Experimental monoclonal antibodies | Contact with infected bodily fluids from a human or zoonotic contact from an infected bat or nonhuman primate Vaccine available for Zaire ebolavirus only |

| Hantavirus | Hantavirus pulmonary syndrome (Americas) Hantavirus renal syndrome (global) | 9 to 33 days | Nonspecific fever, headache, and arthralgia with later findings of acute respiratory distress syndrome or hemorrhagic fever with renal failure Diagnosis via serologic testing and PCR | Supportive care Ribavirin may be used early in hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome | Contact with urine or feces of rodents |

| HIV | Global | 10 days for the acute phase | Nonspecific flulike symptoms; can be widely variable Diagnosis via combination antigen/antibody assay; most develop a positive result 6 weeks after infection | Prompt treatment with antiretrovirals Postexposure prophylaxis must be started within 72 hours of exposure | Travelers who are taking pre-exposure prophylaxis should have proper documentation because these medications can cause confusion in countries that do not allow entry to those with HIV |

| Japanese encephalitis | Asia and Western Pacific; most common in rural agricultural areas | 5 to 15 days | Most cases are asymptomatic or cause nonspecific symptoms of fever, headache, nausea, and vomiting Less than 1% develop encephalitis Neurologic, cognitive, or psychiatric deficits are common among survivors of encephalitis Confirmed via molecular studies on serum or cerebrospinal fluid Must report cases to state and public health authorities | No antiviral available Treatment is mainly supportive | Vaccine preventable Primarily a disease of children in endemic regions |

| Leptospirosis | Global | 2 to 30 days | 90% of all infections are asymptomatic or self-limiting febrile disease Severe disease consists of hepatic and renal failure, jaundice, hemorrhage, meningitis Confirmed with molecular and serologic tests Must report cases to state and public health authorities | Antimicrobial therapy should be initiated as soon as possible, even without a positive test result, if there is a high clinical suspicion Doxycycline for mild disease Intravenous penicillin is recommended for severe disease | Increased incidence in urban areas of developing countries after heavy rainfalls Found in adventure travelers |

| Lyme disease | Southern Scandinavia into the northern Mediterranean, northern China, Russia, Mongolia, northeastern United States | 3 to 30 days | Characteristic rash, erythema migrans, within 30 days of exposure; may cause neurologic and cardiac complications if untreated Diagnosis is mainly clinical but can be confirmed with serologic assays | Most patients can be treated with doxycycline or amoxicillin | Prophylaxis with oral doxycycline as a single 200-mg dose if initiated within 72 hours of tick removal |

| Malaria (Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium knowlesi, Plasmodium malariae, Plasmodium ovale, Plasmodium vivax) | Africa, Southeast Asia, South Asia, South and Central America, and Caribbean | Approximately 7 days Presentation may be delayed for several months after leaving an endemic region | Fevers, chills, headaches, myalgias, and malaise; may also present as fever without a specific or obvious cause or gastrointestinal symptoms in children | Uncomplicated disease World Health Organization recommends artemisinin combination therapy Severe disease: intravenous artesunate | All febrile travelers who have recently returned from a malarious area should be evaluated for malaria P. falciparum causes most severe disease; most prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa P. knowlesi is an emerging infection associated with severe disease; common in Southeast Asia P. vivax and P. ovale require treatment against hypnozoites due to dormant liver stage; obtain glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency levels because primaquine and tafenoquine are associated with hemolytic anemia P. malariae typically causes milder symptoms. |

| Plague | Global | 1 to 6 days | 3 presentations (bubonic, pneumonic, septicemic); bubonic is the most common Rapid fever and swollen lymph nodes Diagnosis via isolation of bacterium, PCR, or culture techniques | Antimicrobial therapy with streptomycin or gentamicin, or ciprofloxacin or doxycycline | Overall risk is low in casual travelers |

| Polio | Global; increased risk in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Syria, Democratic Republic of the Congo | 3 to 6 days for nonparalytic polio 7 to 21 days for paralytic polio | Most cases are asymptomatic or lead to nonspecific self-limiting symptoms Less than 1% of cases lead to paralysis | Supportive management | Vaccine preventable Before traveling to a polio-endemic region, adults who completed a primary immunization series should receive a single lifetime booster |

| Q fever (Coxiella burnetii) | Global with the highest prevalence in Africa and the Middle East | 2 to 3 weeks | Nonspecific flulike symptoms Diagnosis may be clinical; there are serologic, PCR, and staining techniques for confirmation | Doxycycline or fluoroquinolones Pregnant patients and children: trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole | 50% of cases are mild or asymptomatic Exposure to livestock via aerosols |

| Rabies | Global | Variable based on area of exposure but typically weeks to months | Nonspecific prodromal phase with fever to an acute and progressive encephalitis Once clinical symptoms appear, death is imminent | No specific treatment Considered universally fatal | Pre-exposure vaccination for those at higher risk Postexposure prophylaxis depends on previous vaccination (2 doses for those who received pre-exposure prophylaxis and 4 for those who did not) Rabies exposure is estimated at 200 per 100,000 travelers All patients with mammal bites should be medically evaluated Bat bites are of significant concern and warrant postexposure prophylaxis |

| Rickettsiaceae prowazekii and Rickettsiaceae typhi (endemic typhus) | Central Africa; Asia; North, Central, and South America | 7 to 14 days | Nonspecific symptoms, fever, headache, myalgia, red maculopapular rash on trunk Multiorgan failure may occur Clinical diagnosis but may include serology | Doxycycline is highly effective | Incidence increased in overcrowded areas |

| Rickettsial diseases (Rickettsia, Orientia, Ehrlichia, Neorickettsia, Neoehrlichia, Anaplasma) | Global | 7 to 14 days | Nonspecific symptoms, fever, headache, myalgia, red maculopapular rash on trunk Eschar at bite site may occur Multiorgan failure may occur Clinical diagnosis but may include serology | Doxycycline is highly effective | No vaccine is available Antibiotics are not recommended for prophylaxis Avoid contact with animals |

| Scrub typhus (Orientia tsutsugamushi) | Southeast Asia, rural areas in Australia | 10 days | Nonspecific symptoms, fever, headache, myalgia, rash, eschar may develop at bite site Multiorgan failure may occur Clinical diagnosis but may include serology, culture, and PCR | Doxycycline is highly effective | Prophylaxis with oral doxycycline |

| Tetanus (Clostridium tetani) | Global | 10 days; may take up to 21 days | Muscle spasms at injury site that may develop into more generalized spasms with lockjaw Diagnosis is based on clinical history; there is no confirmatory testing | Hospitalization, surgical consultation for wound debridement, supportive care, tetanus immune globulin | Contact with animal saliva (bites) and soil contaminated with animal excrement Vaccine preventable, and all travelers should verify immunization status |

| Tickborne encephalitis | Europe, Asia | 4 to 28 days | Most cases are asymptomatic Nonspecific febrile illness with headache, malaise, and myalgias Some cases cause aseptic meningitis, encephalitis, or myelitis Severity increases with age Diagnosis typically via serology | Supportive care | Most cases occur in Russia, April through November No vaccine is approved in the United States |

| Toxoplasmosis | Global | 5 to 23 days | Nonspecific flulike illness Immunocompromised hosts may develop chorioretinitis, encephalitis, pneumonitis, or disseminated disease Diagnosis typically via serology | Supportive care Treatment with antimicrobials (pyrimethamine, sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine, folinic acid) are typically reserved for pregnant or immunocompromised patients in consultation with infectious disease specialists | Risk factors include exposure to cats, extensive exposure to soil, eating undercooked meat or shellfish, and drinking untreated water |

| Yellow fever | Sub-Saharan Africa, tropical South America | 3 to 6 days | Most cases are asymptomatic or a self-limiting nonspecific febrile illness with headache, myalgia, malaise Approximately 12% of cases develop into severe disease, jaundice, hemorrhagic symptoms, and multiorgan failure (30% to 60% mortality rate) Diagnosis via serology and virus isolation Must report cases to state and public health authorities | Supportive care | Vaccine preventable: recommended for people older than 9 months traveling to endemic regions Some countries mandate proof of vaccine Vaccine provides lifetime immunity |

| Zika virus | Latin America, Caribbean, Africa, Asia, Western Pacific | 3 to 14 days | Most cases are asymptomatic or a self-limiting febrile illness Similar presentation to dengue with maculopapular rash, arthralgia, or conjunctivitis Severe disease is uncommon Diagnosis via serology Must report cases to state and public health authorities | Supportive care | In utero transmission may lead to microcephaly Full range of disabilities is not yet known Pregnant patients should avoid travel to endemic regions If traveling to endemic regions, male partners of pregnant patients should wear barrier protection throughout the duration of pregnancy |

Respiratory Illness

Respiratory infections are common in the United States and throughout the world. Ill returning travelers with respiratory concerns are statistically most likely to have a viral respiratory tract infection.24 Influenza circulates year-round in tropical climates and is one of the most common vaccine-preventable illnesses in travelers.3,12 Influenza A and B frequently present with a low-grade fever, cough, congestion, myalgia, and malaise. eTable C lists the most common causes of respiratory illnesses in the returning traveler.

| Infectious disease | Geographic range | Incubation period | Clinical manifestation/diagnosis | Treatment | Special considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 | Global | 3 to 10 days | Most cases are asymptomatic or self-limiting, although some cause severe pulmonary illness or systemic disease Initial presentation is nonspecific flulike illness; pneumonia sometimes develops Primarily a laboratory diagnosis with antigen or real-time PCR testing widely available | Most cases are self-limiting and require no treatment other than supportive care For those at high risk, consider oral antiviral therapy or human monoclonal antibody infusions | COVID-19 standard and bivalent vaccines are available |

| Diphtheria (Corynebacterium diphtheriae) | Global | 2 to 5 days | Respiratory and cutaneous manifestations Gradual onset with respiratory diphtheria; mild flulike symptoms with sign of a pseudomembrane 2 to 3 days after symptoms (a firm, gray membrane that can extend into the trachea) Diagnosis is mainly clinical, but bacterium can be isolated | Equine diphtheria antitoxin Treatment with erythromycin or penicillin | Vaccine preventable After primary series and childhood and adolescent booster, then booster doses are administered every 10 years with tetanus Must report cases to state and public health authorities |

| Histoplasmosis | Global | 3 to 17 days | Most cases are asymptomatic or mild, self-limiting, nonspecific flulike illness Pulmonary histoplasmosis may present with high fever, nonproductive cough, malaise Diagnosis via culture, serology, and molecular techniques | Most cases are self-limiting and require no treatment other than supportive care For immunocompromised patients, consider fluconazole or itraconazole; for severe cases, amphotericin B | Avoid high-risk activities such as investigating areas occupied by bats |

| Influenza | Global | 1 to 4 days | Most cases are asymptomatic or mild, self-limiting, nonspecific respiratory illness Primarily a laboratory diagnosis with antigen or real-time PCR testing widely available | Most cases are self-limiting and require no treatment other than supportive care For those at high risk, consider oral or intravenous antiviral therapy | Most common vaccine-preventable illness in travelers Influenza has seasonal variation but circulates year-round at the equator |

| Legionella | Global | 2 to 10 days | Legionnaires disease can cause severe pneumonia with fatality rates up to 10% Pontiac fever is the milder form with nonspecific flulike symptoms Diagnosis via urinary antigen test is ideal, with culture and PCR options available | Fluroquinolones or macrolides Patients with Pontiac fever typically do not require antimicrobial therapy | Most common sources of transmission are air conditioners, showerheads, hot tubs, and fountains Travelers older than 50 years, former or current smokers, and those with chronic lung disease or who are immunocompromised are at highest risk |

| Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus | Arabian Peninsula | 2 to 14 days | Clinical course is not fully understood Nonspecific flulike symptoms that may develop into severe acute respiratory syndrome and multiorgan failure; asymptomatic cases have been documented Diagnosis is aided by PCR | Supportive care only | 35% of confirmed cases are fatal |

| Tuberculosis | Global | Approximately 10 weeks | Approximately 10% of immunocompetent people with tuberculosis progress to clinical disease Primarily affects the lungs, but it can affect any organ Diagnosis via tuberculin skin test, QuantiFERON, culture, or chest radiography | Drug-susceptible, drug-resistant, multidrug-resistant, and extensively drug-resistant strains | Bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccine is available for children out-side of the United States |

| Valley fever (coccidioidomycosis) | Western United States, Mexico, Latin America | 7 to 21 days | Most cases are asymptomatic or self-limiting, although some cause pulmonary illness or systemic disease Initial presentation is nonspecific flulike illness Pneumonia and chronic lung disease may develop Diagnosis is clinical but may include serology, culture, PCR | Most cases are self-limiting and require no treatment other than supportive care For immunocompromised patients, consider fluconazole or itraconazole | Outbreaks have been associated with outdoor dust in areas such as construction, military training, and archeologic study sites |

Gastrointestinal Illness

Gastrointestinal symptoms account for approximately one-third of returning travelers who seek medical attention.25 Most diarrhea in travelers is self-limiting, with travelers diarrhea being the most common travel-related illness.7 Diarrhea linked to travel in resource-poor areas is usually caused by bacterial, viral, or protozoal pathogens.

The most often encountered diarrheal pathogens are enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli and enteroaggregative E. coli, which are easily treated with commonly available antibiotics.26 Physicians should be aware of emerging antibiotic resistance patterns across the globe. The CDC offers up-to-date travel information in the CDC Yellow Book.3 Although patients are often concerned about parasites, they should be reassured that helminths and other parasitic infections are rare in the casual traveler.3

The disease of concern in the setting of gastrointestinal symptoms is typhoid fever. Physicians should be aware that typhoid fever and paratyphoid fever are clinically indistinguishable, with cardinal symptoms of fever and abdominal pain.3 Typhoid fever should be considered in ill returning travelers who do not have diarrhea, because typhoid infection may not present with diarrheal symptoms. The likelihood of typhoid fever also correlates with travel to endemic regions and should be considered an alternative diagnosis in patients not responding to antimalarial medications. A diagnosis of enteric fever can be confirmed with blood or stool cultures. Although less common, community-acquired Clostridioides difficile should be considered in the differential diagnosis in the setting of recent travel and potential antimicrobial use abroad.27

Another important travel-related pathogen is hepatitis A due to its widespread distribution in the developing world and the small pathogen dose necessary to cause illness. Hepatitis A is a more serious infection in adults; however, many U.S. adults have been vaccinated because the hepatitis A vaccine is included in the recommended childhood immunization schedule.28 eTable D lists the most common causes of gastrointestinal illnesses in the returning traveler.

| Infectious disease | Geographic range | Incubation period | Clinical manifestation/diagnosis | Treatment | Special considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amebiasis (Entamoeba histolytica) | Global, particularly in the tropics | 1 to 2 weeks | Fever, right upper quadrant pain, weight loss Microscopy, serology, and PCR | Metronidazole | May spread to liver May be sexually transmitted |

| Campylobacteriosis (Campylobacter species ) | Global | 2 to 4 days | Frequent bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting may mimic inflammatory bowel disease or appendicitis Diagnosis is aided by serology, isolation of bacterium in stool studies or PCR Must report cases to state and public health authorities | Self-limiting disease process; however, antimicrobials limit duration of illness Fluoroquinolones are typically used; in areas with resistance to fluoroquinolones, azithromycin is the next best option | One of the most common causes of diarrhea worldwide with low inoculation dose May cause Guillain-Barré syndrome 1 to 3 weeks after onset of symptoms |

| Chagas disease | Mexico, Central and South America | 1 week | Localized swelling at inoculation site; however, most cases are asymptomatic; infection remains throughout life Diagnosis is aided by direct visualization of parasite, serology, and PCR techniques | Nifurtimox (Lampit) and benznidazole All acute cases must be treated | 30% of patients develop chronic symptoms that usually affect the heart Presentation includes arrhythmias and cardiomyopathy May also cause megacolon |

| Cholera (Vibrio cholerae) | Southern and Southeast Asia, Africa, Caribbean | 2 hours to 5 days | Watery diarrhea, “rice-water stools,” nausea, and vomiting Stool culture | Rehydration is the most important treatment (< 1% of cases are fatal if proper rehydration is performed) Doxycycline is first-line treatment, although drug resistance is emerging | Minimal risk when proper handwashing, food, and water recommendations are followed Rapid dehydration possible Vaccine available to those traveling to endemic regions |

| Giardiasis (Giardia) | Global | 1 to 2 weeks | Greasy diarrhea (2 to 5 loose stools per day), abdominal pain, nausea Fever and vomiting are uncommon Diagnosis via stool studies or PCR | Metronidazole | Top 10 diagnosis in ill travelers returning to the United States Backpackers who spend longer times in rural areas are at increased risk by drinking water from untreated sources |

| Hepatitis A | Global with a high prevalence in Asia and Africa | Average is 28 days | Nonspecific fever, fatigue, anorexia, and abdominal pain Jaundice may be seen, symptoms last weeks to months, severe cases may lead to liver failure Diagnosis via serology | Supportive care | Vaccine preventable and should be offered to all susceptible travelers Vaccine is considered safe for pregnant individuals |

| Hepatitis B | Global with a high prevalence in Asia and Africa | Average is 90 days | Nonspecific fever, fatigue, anorexia, abdominal pain Jaundice may be seen Diagnosis via serology | Supportive care for acute infections Antiviral medication for chronic infections | Major cause of chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma globally Vaccine preventable and should be offered to all susceptible travelers |

| Hepatitis C | Global with a high prevalence in eastern Europe, Africa, Asia | 2 to 24 weeks | Nonspecific fever, fatigue, anorexia, and abdominal pain Jaundice may occur Serologic testing and PCR for confirmation | Supportive care for acute infections Antiviral medication for chronic infections | When seeking medical care abroad, ensure equipment has been properly sterilized Blood donors throughout Africa are not routinely screened for hepatitis C Acquiring tattoos abroad increases risk |

| Leishmaniasis (visceral) | Most cases are from India, East Africa, Brazil Old World: Middle East, Southwest and Central Asia, Africa, southern Europe New World: Mexico, Central and South America | Weeks to months | May be abrupt or gradual onset with fever, abdominal pain, hepatosplenomegaly, and pancytopenia Diagnosis is clinical, aided by culture, light microscopy, and molecular techniques | Treatment should be in consultation with infectious disease, tropical medicine, and CDC experts Amphotericin B is typically used in the United States; other agents include miltefosine and pentostam | Most common in rural areas with exposure to sand flies The highest risk of exposure is during dusk and dawn Untreated cases are typically fatal |

| Loeffler syndrome (Ascaris lumbricoides) | Global | Variable; usually 4 to 8 weeks | Asymptomatic to vague abdominal pain or discomfort, nausea, bloating, and change in stool patterns | Treatment of choice is albendazole | Transient respiratory symptoms in the initial phase of the infection |

| Strongyloides stercoralis | Tropics | 2 to 4 weeks | Most infections are asymptomatic Localized, pruritic, erythematous papular rash at the site of exposure May develop pneumonitis, diarrhea, and eosinophilia Diagnosis is aided by serology and direct visualization from stool studies | Ivermectin | Prevention is key: wear shoes when walking in areas where human or animals may have defecated |

| Taenia solium (cysticercosis) | Global | Latent period may last months to years | Most common clinical manifestations are seizures and increased intracranial pressure Rule out disease in any adult who has new-onset seizures Neuroimaging with computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging followed by serologic testing | Treatment in consultation with infectious disease, tropical medicine, or CDC experts Supportive care and anticonvulsants Surgical therapy may be needed in some cases Albendazole may be used in some cases | Uncommon in travelers but seen regularly in immigrants from endemic regions (Latin America, Asia, Africa) |

| Travelers diarrhea (enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli) | Global | 2 to 10 days | Frequent, loose, watery bowel movements with abdominal cramping, bloating, and malaise Stool culture and PCR assays | Generally self-limiting illness, antibiotics often not necessary Loperamide Antibiotics to limit downtime while traveling Ciprofloxacin and azithromycin are common options | Serious illness is rare |

| Typhoid and paratyphoid fever (Salmonella typhi and Salmonella paratyphi) | Global with particular concern for travelers to Africa, southern and Southeast Asia | 6 to 30 days | Gradual onset with fever, abdominal pain, nausea vomiting, diarrhea, and malaise Fever spikes in the afternoons, especially on the third and fourth days after symptoms appear May be confused with malaria Diarrheal symptoms may not be present Blood culture is the standard for diagnosis | Fluroquinolones have been treatment of choice; however, there is emerging resistance, especially in Southeast Asia Azithromycin or ceftriaxone should be used for fluoroquinolone-resistant infections | Vaccine preventable for S. typhi There is currently no vaccine available for S. paratyphi Extremely drug-resistant S. typhi and S. paratyphi are of grave importance, with 60% of child travelers requiring hospitalization Vaccination is critical for prevention; most hospitalized patients were not vaccinated |

Dermatologic Concerns

Dermatologic concerns are common among returning travelers and include noninfectious causes such as sun overexposure, contact with new or unfamiliar hygiene products, and insect bites. The most common infections in returning travelers with dermatologic concerns include cutaneous larva migrans, infected insect bites, and skin abscesses. Cutaneous larva migrans typically presents with an intensely pruritic serpiginous rash on the feet or gluteal region.3 Questions about bites and bite avoidance measures should be asked of patients with symptomatic skin concerns; however, physicians should remember that many bites go unnoticed.29

Formerly common illnesses in the United States are common abroad, with measles, varicella-zoster virus infection, and rubella occurring in child and adult travelers.3 Measles is considered one of the most contagious infectious diseases. More than one-third of child travelers from the United States have not completed the recommended course of measles, mumps, and rubella vaccines at the time of travel due to immunization scheduling. One-half of all measles importations into the United States comes from these international travelers.30 Measles should always be considered in the differential because of the low or incomplete vaccination rates in travelers and high levels of exposure in some areas abroad. eTable E lists the most common infectious causes of dermatologic concern in the returning traveler.

| Infectious disease | Geographic range | Incubation period | Clinical manifestation/diagnosis | Treatment | Special considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B virus (herpesvirus B) | Africa, Asia, South America, Caribbean | Usually within 1 month but may be as early as 3 to 7 days | Vesicular-like rash near inoculation site with flulike symptoms; neurologic symptoms are a late manifestation Diagnostic testing of human specimens is performed only at the National B Virus Resource Center | Postexposure prophylaxis with valacyclovir or acyclovir Intravenous acyclovir or ganciclovir (Cytovene) once B virus infection has been diagnosed | Fewer than 50 cases have been documented in the United States since 1932 Encephalomyelitis is often fatal despite treatment |

| Cutaneous larva migrans (Ancylostoma) | Macaque monkeys are the natural reservoir (Asia and Africa) | 1 to 5 days but may take up to 1 month | Eruption with erythematous tracking (serpiginous) that is intensely pruritic The feet and gluteal regions are the most common sites Clinical diagnosis only | Self-limiting with symptomatic treatment Rash resolves within 6 weeks Albendazole is very effective | Use barrier clothing when on beaches Avoid exposure to cat and dog feces |

| Leishmaniasis (cutaneous) | Old World: Middle East, Southwest and Central Asia, Africa, and southern Europe New World: Mexico, Central and South America | 1 to 6 months | Small papules that develop into a nonhealing open sore with a raised border and central ulceration Lesions are usually painless Diagnosis is clinical, aided by culture, light microscopy, and molecular techniques | Treatment should be based in consultation with infectious disease or tropical medicine specialists Miltefosine may be used for New World species; do not use in those who are pregnant or breastfeeding Pentostam is available through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for intravenous treatment | Most common in rural areas with exposure to sand flies The highest risk of exposure is during dusk and dawn Mucosal leishmaniasis typically develops from untreated cutaneous leishmaniasis years later May affect the nose, sinuses, and, less often, the mouth |

| Loa loa (loiasis) | West or Central Africa | 3 to 4 years | Calabar swellings (erythematous, pruritic nodules noted under the skin) Microscopy of blood for the visualization of microfilariae | Treatment of choice is diethylcarbamazine combined with ivermectin Treatment should be based in consultation with infectious disease or tropical medicine specialists | — |

| Measles | Global | 7 to 21 days | Nonspecific flulike illness with a maculopapular rash developing around 14 days after exposure (3 to 7 days after prodrome starts) Koplik spots: small white spots on the inside of the buccal mucosa Diagnosis via serology, polymerase chain reaction, or isolation of virus Must report positive cases to public health authorities | Supportive care Vitamin A supplementation is recommended for cases in the developing world | Vaccine preventable Typically the patient is contagious from 4 days before until 4 days after rash onset One of the most contagious viruses known; humans are the only natural host |

| Meningococcal meningitis (Neisseria meningitidis) | Endemic to West and Central Africa | 1 to 10 days | Clinical manifestations ranging from asymptomatic, dermatologic manifestations such as petechiae, to severe systemic/neurologic disease | Many antimicrobial treatment options available; treatment should be based in consultation with infectious disease specialists | Vaccines are widely available, targeting A, B, C, Y, W-135 Seasonal variance noted in Africa Meningitis belt in sub-Saharan Africa; extends from Senegal to Ethiopia |

| Mpox (monkeypox) | Global | 5 to 17 days | Prodrome fever followed by vesicular rash that can involve palms and soles Significant lymphadenopathy Polymerase chain reaction can help with diagnosis | Treatment is mainly supportive because lesions resolve by 2 to 4 weeks Tecovirimat (Tpoxx) for severe cases | Ongoing 2022 outbreak in Europe and Americas spread most often via sexual contact |

| River blindness (Onchocerca volvulus) | Sub-Saharan Africa, Brazil, Venezuela, Yemen | Approximately 18 months | Intensely pruritic, papular dermatitis, lymphadenitis, subcutaneous nodules, and ocular involvement that may lead to blindness Diagnosis is aided by visualization of worms on biopsy | Ivermectin | Travelers typically present with a rash |

| Scabies | Global | 2 to 6 weeks, although symptoms may appear sooner if previously had scabies | Clinical diagnosis with characteristic rash in skinfolds | Topical permethrin or oral ivermectin | Higher prevalence in travelers who are abroad > 2 months Treat close contacts |

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed using the key words prevention, diagnosis, treatment, travel related illness, surveillance, travel medicine, chemoprophylaxis, and returning traveler treatment. The search was limited to English-language studies published since 2000. Secondary references from the key articles identified by the search were used as well. Also searched were the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Cochrane databases. Search dates: September 2022 to November 2022, March 2023, and August 2023.

The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the U.S. Army, the U.S. Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.