This is a corrected version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(4):386-395

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

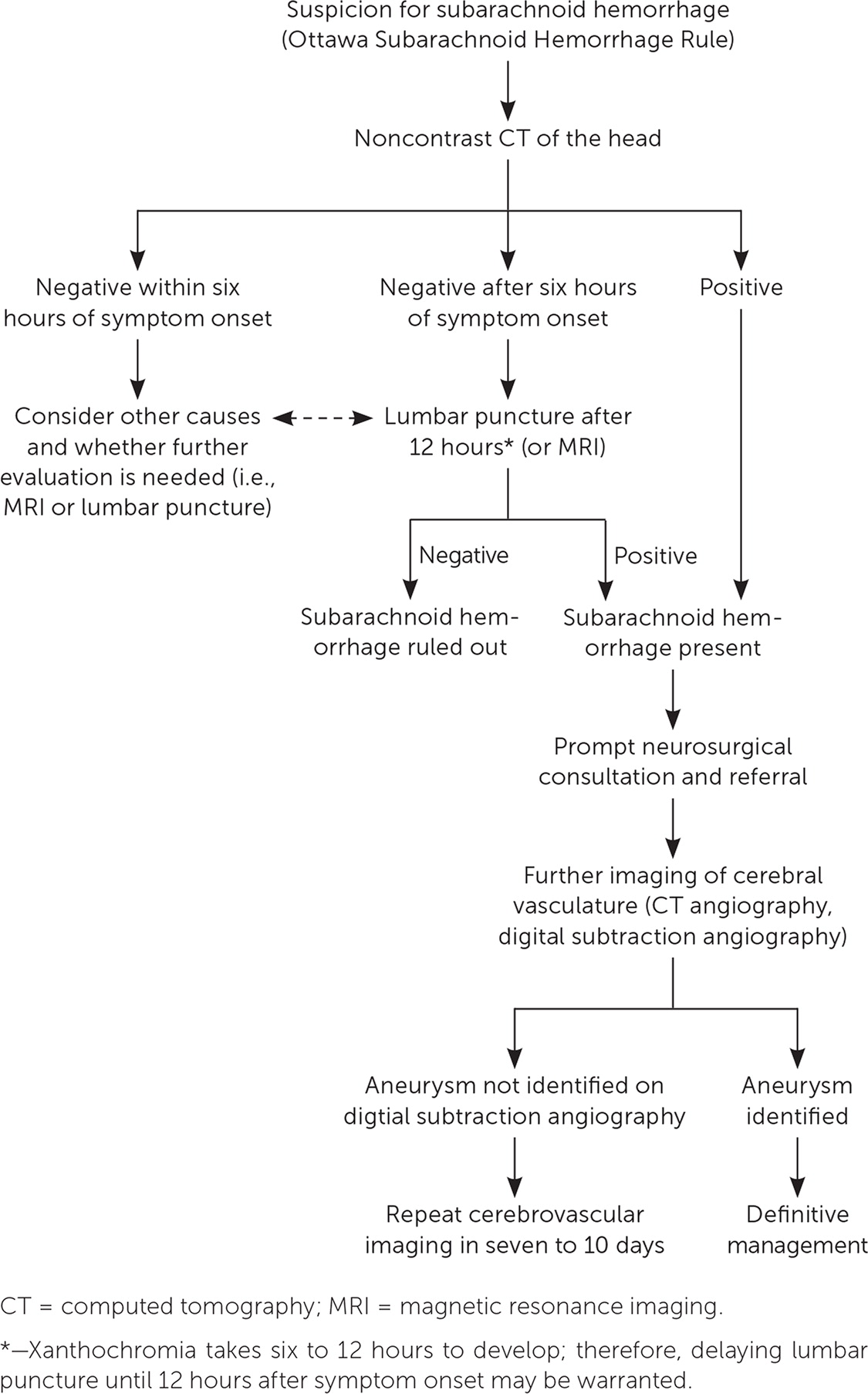

Subarachnoid hemorrhage caused by a ruptured intracranial aneurysm is a neurosurgical emergency with a mortality rate of approximately 50%. Prompt identification and treatment of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage are paramount to reduce mortality, long-term morbidity, and health care burden for survivors. The prevalence of intracranial aneurysms is 2% to 6% of the global population, many of which are found incidentally during workup for an unrelated condition. Screening is not recommended for the general population and should be reserved for patients who have at least one family member with a history of intracranial aneurysm or subarachnoid hemorrhage or when there is a high index of suspicion for those with certain medical conditions associated with an increased incidence of intracranial aneurysms. Physicians who treat patients with headache should be aware of the spectrum of clinical presentation of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage because not all patients present with the classic thunderclap headache. The Ottawa Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Rule is a validated clinical decision tool to help determine which patients with a sudden, acute headache require imaging with noncontrast computed tomography. Based on the results of initial computed tomography and duration of symptoms, the patient may require a lumbar puncture or additional imaging to confirm the diagnosis. Prompt diagnosis of an aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage is essential to patients receiving definitive treatment.

Aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is caused by the rupture of an intracranial aneurysm.1 Most intracranial aneurysms are found incidentally during the workup for another condition. Although intracranial aneurysms are common, only 0.25% of them rupture annually. An aneurysmal SAH is a neurosurgical emergency that results in significant morbidity and mortality.2 Prompt diagnosis and treatment are essential to minimize rebleeding, prevent further neurologic injury, and reduce mortality. The classic symptom of a sudden, severe thunderclap headache is absent in 25% of patients with an aneurysmal SAH; therefore, physicians should have a high index of suspicion in patients presenting with a new or worsening headache. Rapid diagnosis and treatment of aneurysmal SAH require patient stabilization, imaging, and early consultation with a neurosurgeon.3

Epidemiology

Intracranial aneurysms are prevalent in 2% to 6% of the global population, and 1 in 50 Americans has an intracranial aneurysm.2,4 The annual incidence of aneurysmal SAH in the United States is 14.5 per 100,000 people, accounting for 3% of hemorrhagic strokes, and is associated with a 50% mortality rate.1,2,5 Approximately 10% to 15% of patients who have an aneurysmal SAH will die before reaching the hospital, and 30% to 60% never recover from the initial hemorrhage and will die within 30 days.6 Of those who survive, 30% to 50% have significant neurologic morbidity that affects quality of life and contributes to an enormous financial health care burden.4,7–11 Rebleeding from the culprit aneurysm, a major complication of aneurysmal SAH, often occurs in the first 72 hours of the initial hemorrhage and has a 20% to 60% mortality rate. Thirty percent of patients who are admitted with an aneurysmal SAH will rebleed in one to six months if the aneurysm is not properly identified and treated, reinforcing the need for timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment of the aneurysm.12–14

Risk Factors and Screening

Risk factors for the development of an intracranial aneurysm and rupture have been identified and categorized into modifiable and nonmodifiable factors (Table 1).1,8,15–17 Modifiable risk factors include hypertension, tobacco use, consuming more than two alcoholic drinks per day, cocaine use, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus, and possibly insomnia and sleep apnea.15–18

| Modifiable risk factors Alcohol use Cocaine use Diabetes mellitus Hypercholesterolemia Hypertension Sleep apnea Smoking tobacco Nonmodifiable risk factors Family history of intracranial aneurysm in a first-degree relative Female sex Genetic and medical conditions listed in Table 2 Older age | Factors associated with an increased risk of rupture Aneurysms with daughter sac formation Cocaine abuse Growing or giant aneurysms Hypertension Japanese and Finnish descent* Posterior circulation or posterior communicating artery aneurysms Postmenopausal women Smoking tobacco |

The nonmodifiable risk factors for intracranial aneurysm are female sex, older age, and a family history of an intracranial aneurysm or aneurysmal SAH, as well as several other congenital conditions.

The female to male incidence ratio of intracranial aneurysm is 1: 1. This ratio increases, however, after female menopause to 2: 1.19 The increased prevalence in postmenopausal females is likely related to decreasing estrogen levels that lead to lower vascular collagen levels and subsequent weakening of arterial walls.7

The familial occurrence rate for an intracranial aneurysm is 7% to 20% and the risk is 3.6 times higher for those with a family history vs. those without. Patients with one first-degree relative with an intracranial aneurysm have a 4% higher risk of having an intracranial aneurysm, and those with two first-degree relatives have an 8% to 10% higher risk. Patients with autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease are 10% to 13% more likely to have an intracranial aneurysm vs. those without.4 Because of the significant morbidity and mortality associated with aneurysmal SAHs, it has been postulated that early identification and treatment of asymptomatic intracranial aneurysms may be beneficial. However, mathematical screening models demonstrate that global screening for intracranial aneurysms would result in the loss of quality-adjusted life-years and may be harmful due to the excessive annual radiation exposure through frequent imaging.2 Therefore, the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association guidelines do not recommend screening for intracranial aneurysms in the general population.2,5,20 However, screening by computed tomography (CT) angiography or magnetic resonance angiography is reasonable for patients who have at least one family member with a history of intracranial aneurysm.2,5,20 Current screening guidelines also recommend offering screening to patients who have certain medical conditions that increase the risk of developing intracranial aneurysms (Table 22,4,7,21,22).

| Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency Aortic aneurysm Autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease Bicuspid aortic valve Coarctation of aorta Ehlers-Danlos syndrome IV Familial aldosteronism type 1 Fibromuscular dysplasia Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia Intracranial arteriovenous malformation | Klinefelter syndrome Loeys-Dietz syndrome Microcephalic osteodysplastic primordial dwarfism Moyamoya disease Multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 Neurofibromatosis Noonan syndrome Pheochromocytoma Sickle cell anemia or sickle cell disease Tuberous sclerosis |

Anatomy

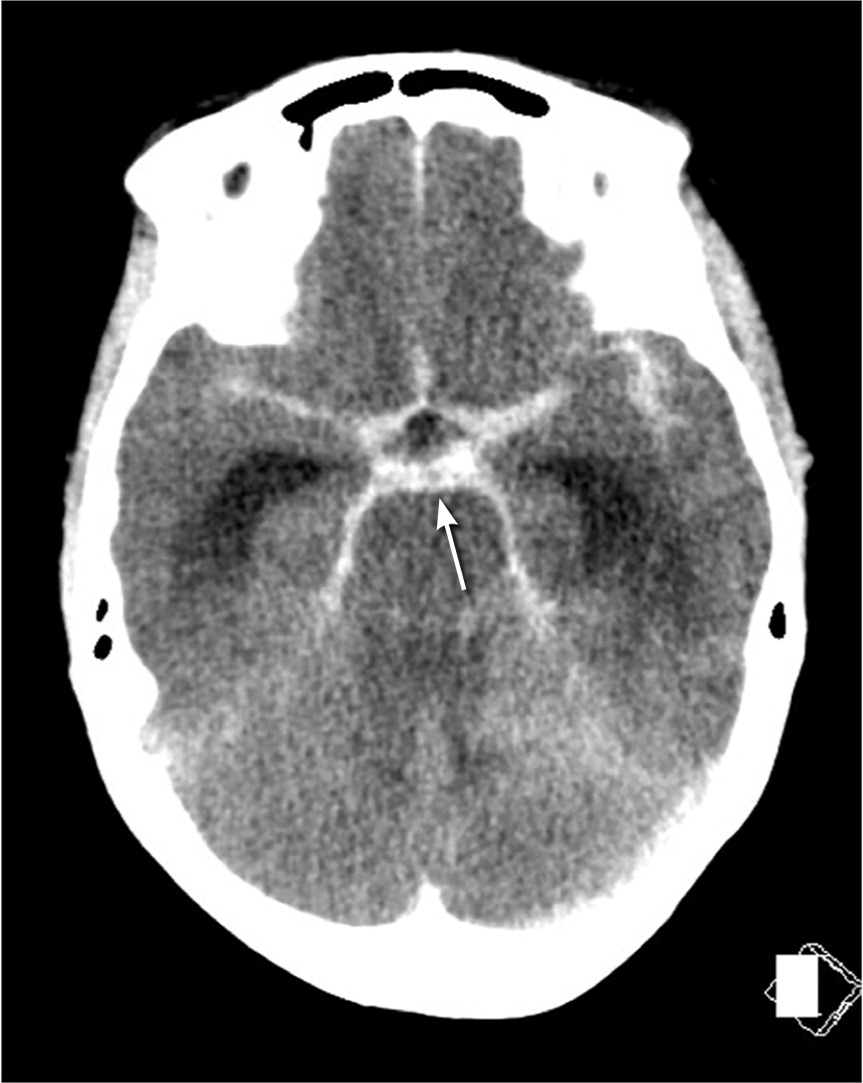

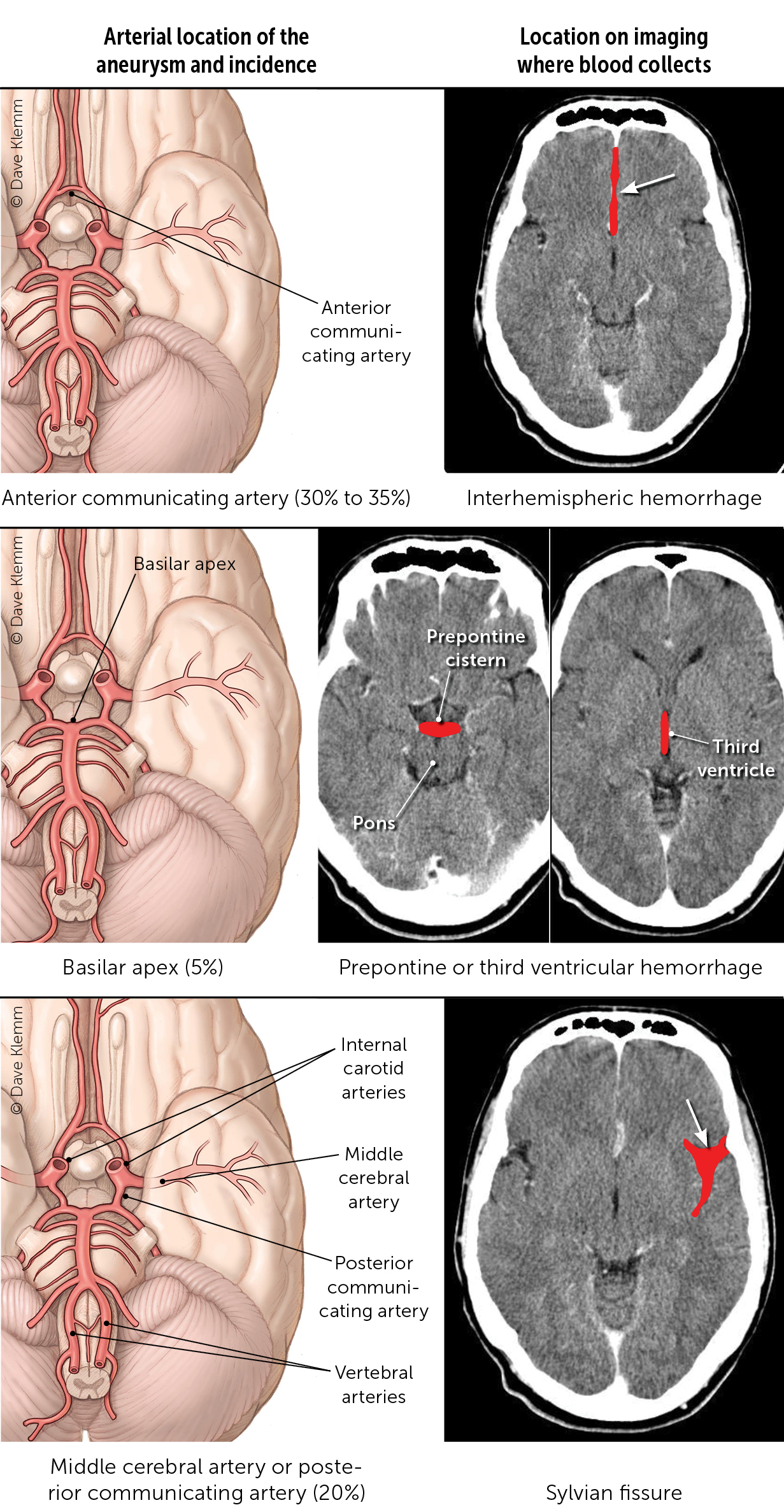

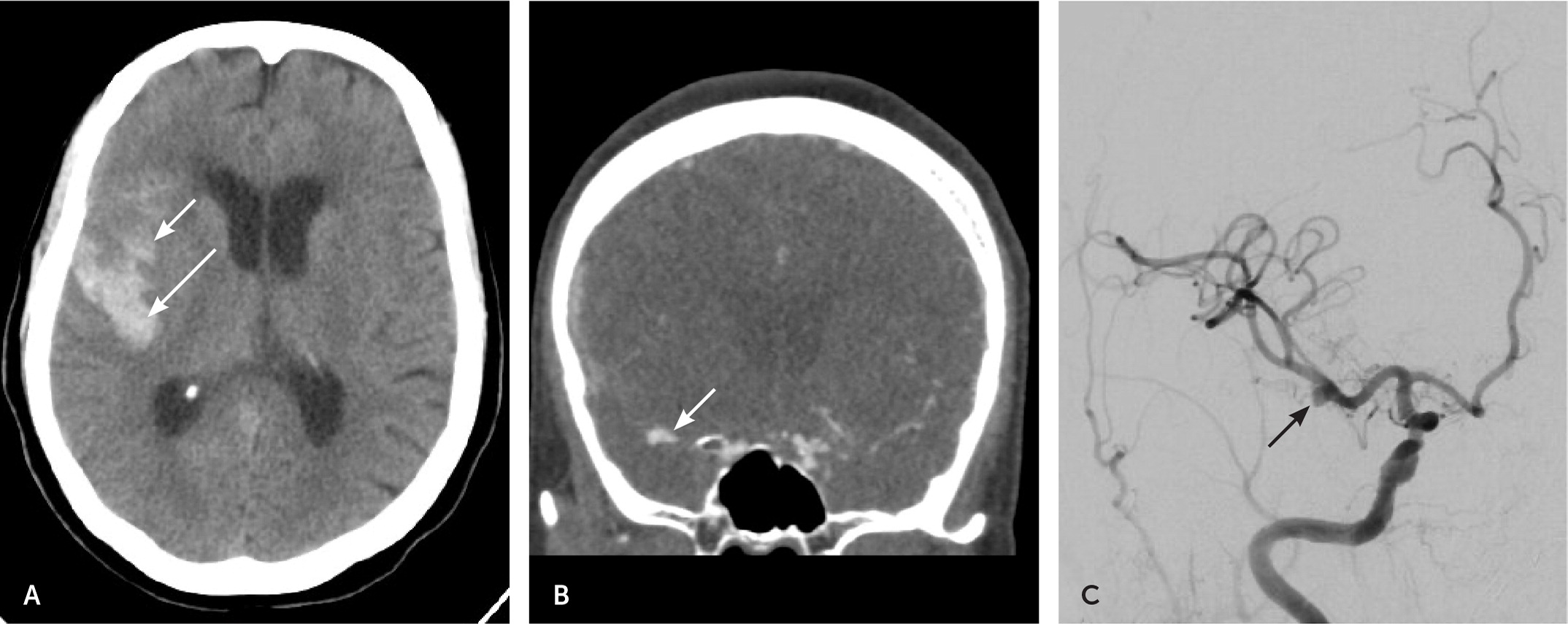

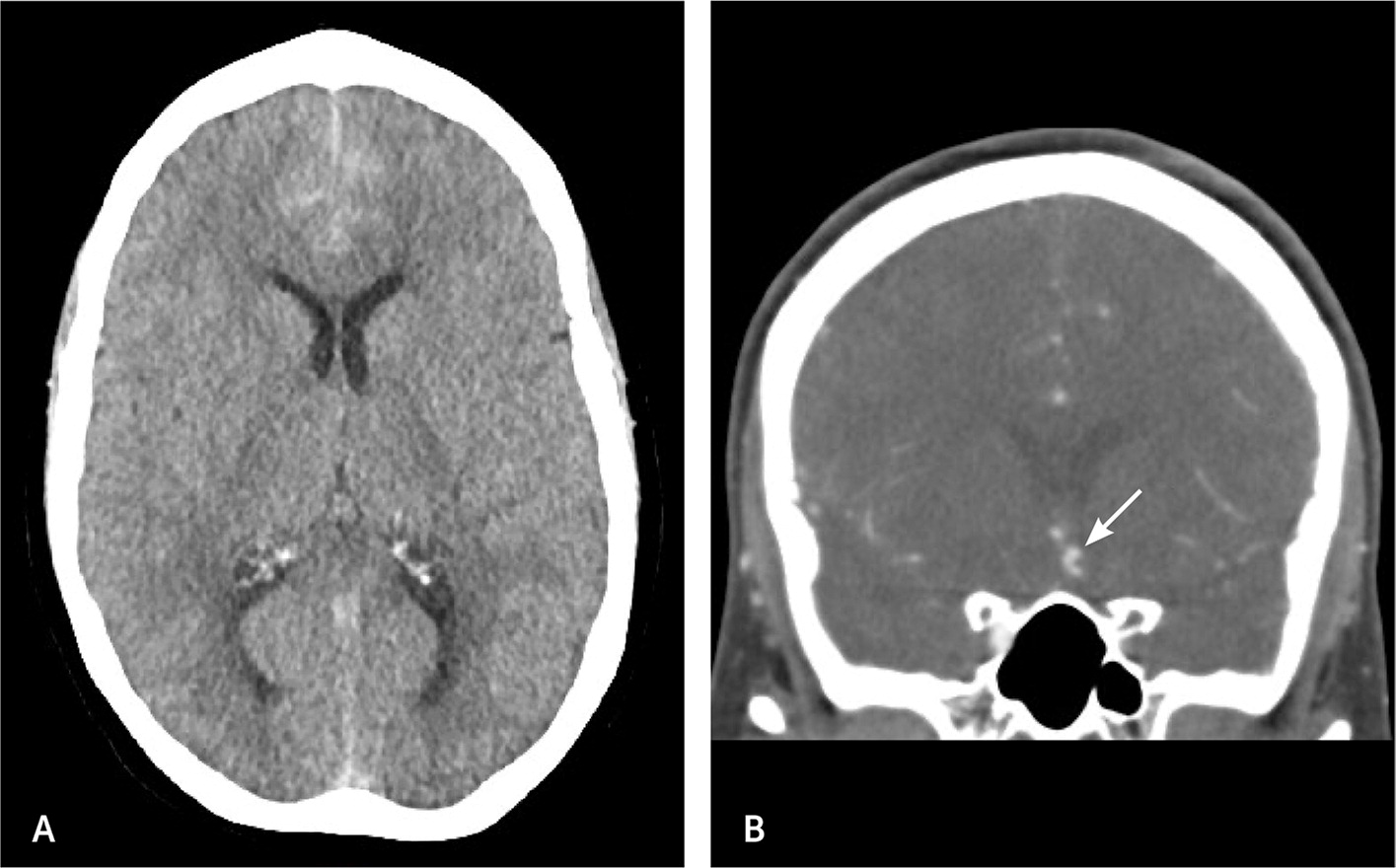

There are four main vessels that provide the entirety of blood flow to the brain, specifically the bilateral internal carotid and vertebral arteries. These arteries converge and have branches that form the circle of Willis. This high-flow arterial system with numerous branch points leads to turbulent flow and shear stress within the walls of the artery. It is unclear what ultimately weakens the arterial wall, but a combination of genetic, proinflammatory, and patient characteristics (e.g., smoking, atherosclerosis, hypertension) results in aneurysm dilation and progression.9,23 Aneurysms are most commonly located along the anterior communicating, carotid, and middle cerebral arteries. However, aneurysms found in the posterior circulation and posterior communicating arteries have the highest risk of rupture.19,21 When aneurysmal rupture occurs, arterial blood hemorrhages into the subarachnoid cisterns that house the circle of Willis and is typically visible on non-contrast CT of the head (Figure 1). Figure 2 shows the location of blood on imaging based on aneurysm location.16,17,21 [corrected]

Clinical Presentation

Spontaneous, nontraumatic SAH caused by a ruptured intracranial aneurysm is a neurosurgical emergency. Prompt recognition, evaluation, and diagnosis are essential to minimize the high morbidity and mortality associated with aneurysmal SAH.24 Aneurysmal SAH classically presents as a sudden, severe, thunderclap headache that reaches maximum intensity in less than one minute and is commonly described as the worst headache of the patient’s life.25 Hallmark signs and symptoms include onset during exertion, sudden buckling of the legs, transient loss of consciousness, vomiting, photophobia, neck stiffness, or focal neurologic deficits.26–28 Seizure at the onset of a headache is also a strong indicator for aneurysmal SAH.3 Although patients with an aneurysmal SAH typically present with a sentinel or thunderclap headache, many will have milder symptoms and approximately 40% will be neurologically intact on presentation.29,30 Importantly, 10% to 43% of patients will experience a less severe sentinel headache in the days or weeks before an aneurysmal SAH that is caused by early leakage and enlargement of the aneurysm.31

Despite the wide availability of neuroimaging, misdiagnosis of aneurysmal SAH remains high, particularly in patients with no neurologic deficits.32 The most common reasons for misdiagnosis are physicians not recognizing that the patient’s symptoms could be from a ruptured intracranial aneurysm, failure to perform CT and understand its limitations, or failure to perform lumbar puncture when there is a negative CT scan but high suspicion for aneurysmal SAH.28,33

Initial Evaluation

The initial evaluation should include a physical examination to assess the patient’s level of consciousness, presence of focal neurologic deficits, and meningeal signs.34 Retinal or intraocular hemorrhages may be identified if funduscopy is performed. Intraocular hemorrhage from an aneurysmal SAH (Terson syndrome) occurs in up to 46% of patients and is caused by a sudden increase in intracranial pressure. It is associated with a poor prognosis and higher rate of mortality.35,36

Validated clinical decision tools are available to determine which patients with headache are at high risk of aneurysmal SAH and should receive prompt neuroimaging. The Ottawa SAH Rule is widely used to help physicians identify patients at risk for an aneurysmal SAH who present with a headache without neurologic deficits. The Ottawa SAH Rule is appropriate for patients older than 15 years with new, severe, nontraumatic headaches that reach maximum intensity within an hour. It is not appropriate for those with new neurologic deficits or a history of aneurysms, SAH, tumors, or recurrent headaches. Patients with at least one of the following variables should be referred for immediate imaging: 40 years and older, neck pain or stiffness, witnessed loss of consciousness, onset during exertion, thunderclap headache, and limited neck flexion on examination. It has been found to be 99.5% to 100% sensitive and approximately 8% to 24% specific.37,38 Although originally designed and studied in the emergency department, it is a useful tool for physicians in an outpatient setting.

Diagnostic Imaging

Noncontrast CT of the head is the imaging modality of choice in the initial evaluation of aneurysmal SAH in patients presenting with a sudden onset headache.26,39 It is nearly 100% sensitive and specific if performed within six hours of symptom onset, and 86% to 97% sensitive if performed within six to 72 hours.12,40–42

Appreciating vascular neuroanatomy allows the physician to better differentiate aneurysmal SAH from other types of intracranial hemorrhage seen on noncontrast CT.

SAH can have a variety of appearances on imaging depending on the underlying etiology. Aneurysmal SAH is commonly seen on noncontrast CT as a hyperdense collection of blood in the subarachnoid cisterns43 (Figure 3 and Figure 4). Alternatively, SAH caused by trauma typically shows blood along the brain convexity. Although hemorrhage caused by arteriovenous malformation may have a subarachnoid component, a ruptured arteriovenous malformation is more likely to be associated with an intraparenchymal or intraventricular hemorrhage and frequently shows calcifications on imaging.44

Epidural and subdural hematomas are common, hyperdense findings seen on CT, not to be confused with SAH. Epidural hematomas tend to occur in younger patients following a traumatic event and are associated with a lucid interval.45 Transection of the middle meningeal artery due to a temporal bone fracture is the most common cause of epidural hematoma. On non-contrast CT, an epidural hematoma appears as a hyperdense convex- or lentiform-shaped lesion that does not extend beyond the suture lines (Figure 5) and has a vastly different appearance than a SAH.

Subdural hematomas occur secondary to significant rotational forces that tear bridging veins that travel from the cerebral cortex through the subdural space and into the venous sinuses.46 A subdural hematoma on CT appears as a hyperdense or hypodense (depending on chronicity), concave- or crescent-shaped lesion adjacent to the brain parenchyma (Figure 6). It is important to understand the radiographic difference between these pathologies because patients with a ruptured intracranial aneurysm are frequently found comatose or unresponsive, and the precise history may not be apparent.

Additional Evaluation

Patients with a negative CT scan obtained promptly following headache onset and who are neurologically intact may not need a lumbar puncture for cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis due to the high sensitivity of CT and low sensitivity of lumbar puncture in the acute time frame.13,41,47 If the initial noncontrast head CT scan is negative and there is a high index of suspicion for aneurysmal SAH, a lumbar puncture should be considered ideally within six to 12 hours of symptom onset.47 Findings from lumbar puncture that are consistent with aneurysmal SAH are elevated opening pressure, erythrocytosis that does not decline from tubes 1 to 4 (discordant with what is seen in a traumatic tap), and the presence of xanthochromia.20,40,41,48 Xanthochromia is the yellowing of the CSF and takes approximately six to 12 hours to develop after hemorrhage. It is caused by the presence of bilirubin in the CSF from red blood cell dilution and degradation.25 Xanthochromia is preferably detected by spectrophotometry but may be done by visual inspection if spectrophotometry is not available.48,49 Visual detection of xanthochromia is performed by comparing a vial of CSF with a vial of water held against a bright light and a white background.50

If the initial head CT scan is negative, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be an acceptable alternative to lumbar puncture in the evaluation of aneurysmal SAH, especially in patients presenting days following headache onset.20 Time constraints and availability may limit the utility of MRI in the early evaluation of aneurysmal SAH. MRI is also limited in detecting SAH in the anterior midbrain (perimesencephalic region), which accounts for 38% of nontraumatic SAH.51,52 Therefore, in certain clinical situations, even if the MRI is negative, a lumbar puncture should be considered.

Once aneurysmal SAH is detected, CT angiography or digital subtraction angiography should be performed to visualize the cerebral vasculature, identify the culprit aneurysm, and guide treatment.51 Although digital subtraction angiography is the preferred method for imaging the cerebral vascular anatomy and is superior to CT angiography at detecting small aneurysms, it is associated with a 1.8% higher risk of neurologic complications or rebleeding because it is more invasive.53,54 If the culprit aneurysm or specific source of bleeding is not initially identified, which occurs in approximately 15% of cases, repeat digital subtraction angiography should be considered after seven days.52 The patient remains in the hospital during this period and is monitored closely. Timely, safe, and precise identification and characterization of the culprit aneurysm are essential to guide treatment and prevent rebleeding. An algorithm for the evaluation of SAH is shown in Figure 7.17,45

Clinical Assessment Tools

Standardized grading scales for aneurysmal SAH are used to estimate disease severity and provide prognostic information (Table 3).19,55,56 The most used clinical scales are the Hunt and Hess and World Federation of Neurological Surgeons scales.19,25,55 Because of the clinical severity and associated high morbidity, patients with Hunt and Hess scale grade 5 typically do not receive treatment to secure their aneurysm until they show neurologic improvement. The Modified Fisher scale is a radiologic scale used to grade the amount of subarachnoid blood on CT and correlates with the risk of cerebral vasospasm that results in cerebral ischemia and stroke.56 Higher scores on any of these scales correlate with increasing SAH severity and poorer long-term outcomes. [corrected]

| Hunt and Hess scale | Grade | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Clinical condition | No or mild headache, no or minimal nuchal rigidity | Moderate to severe headache, nuchal rigidity, no neurologic deficits other than possible cranial nerve palsy | Drowsiness, confusion, mild focal deficit | Stupor, moderate to severe hemiparesis | Comatose, decerebrate rigidity |

| Modified Fisher scale | Grade | ||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Subarachnoid hemorrhage | None | Thin (< 1 mm) | Thin | Thick (> 1 mm) | Thick |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage | None | None | Present | None | Present |

| World Federation of Neurological Surgeons scale | Grade | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Glasgow Coma scale | 15 | 13 to 14 | 13 to 14 | 7 to 12 | < 7 |

| Neurologic examination | No motor deficit | No motor deficit | With focal motor deficit | With or without motor deficit | With or without motor deficit |

Treatment and Prognosis

After initial assessment and medical stabilization, which should include endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation, if needed, systolic blood pressure should be monitored by an arterial line and kept at less than 140 mm Hg to decrease the risk of aneurysmal rebleeding. The patient should be maintained in a euvolemic state and started on antiepileptic medication and nimodipine to prevent seizures and minimize the risk of rebleeding.57,58 Detailed treatment options are outside the scope of this article but include open craniotomy for aneurysm clipping, bypass, or wrapping and endovascular treatments such as coiling, stent-assisted coiling, or flow diversion.8 Patients should be cared for in an appropriate facility staffed with neurosurgeons and endovascular and neurocritical care specialists.20

Despite advances in diagnostic imaging and treatment, there are still high rates of mortality and morbidity associated with aneurysmal SAH. Multiple independent factors play a role in the outcome and include, but are not limited to, the size and severity of the initial hemorrhage; patient age; intracranial complications, such as rebleeding, delayed cerebral ischemia, or hydrocephalus; and treatment-related complications.6

Early diagnosis provides the best chance of a positive outcome for a patient with aneurysmal SAH. Clinicians caring for patients who present with a headache should be aware of the spectrum of presentation of aneurysmal SAH, clinical assessment tools, and appropriate neuroimaging modalities to minimize the likelihood of missing a SAH.

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Cohen-Gadol and Bohnstedt.33

Data Sources: A PubMed search was performed for meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, and clinical reviews. Key search terms were intracranial aneurysms (IA), subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), aneurysm subarachnoid hemorrhage (aSAH), and thunderclap headache. Essential Evidence Plus and UpToDate were also searched. Whenever possible, if studies used race and/or gender as patient categories but did not define how these categories were assigned, they were not included in our final review. If studies that used these categories were determined to be essential and therefore included, limitations were explicitly stated in the manuscript. Search dates: September and November 2022, and June 2023.