This is a corrected version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(4):378-385

Patient information: See related handout on the undescended testicle.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Cryptorchidism refers to an undescended testicle, the most common genitourinary malformation in male children. It is diagnosed with history and physical examination findings, and primary care physicians play a key role in the early identification of the condition. Early surgical intervention reduces the risk of testicular cancer and preserves fertility. Patients should be referred for surgical intervention at six months of age or at the time of diagnosis if the child is older. After surgery, patients require lifelong surveillance and counseling regarding fertility implications and increased risk of testicular conditions. Patients with bilateral undescended testicles that are nonpalpable should undergo endocrinologic evaluation for sexual development disorders. Retractile testicles are a variant of cryptorchidism and should be monitored annually until puberty, when acquired ascent becomes unlikely due to greater testicular volume. Based on expert opinion, all patients with a history of cryptorchidism should undergo annual clinical examination and be taught self-examination techniques for early detection of testicular cancer.

Cryptorchidism is a condition in which a testicle has not descended to its proper position in the scrotum. It is the most common genitourinary malformation in male children and affects 45% of preterm and 1% to 4% of term male infants.1 Cryptorchidism presents unilaterally in 90% of cases, and the right testicle is most often affected.2 The etiology is unknown but is associated with birth weight less than 2,500 g, intrauterine growth restriction, preterm gestational age, and perinatal asphyxia. A family history of cryptorchidism, hormone and sex disorders, and penile abnormality increases the risk of cryptorchidism. The risk is also increased with pregnancies complicated by obesity, advanced maternal age, placental insufficiency, and cesarean delivery.1–3

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Serial examination is recommended for diagnosis of cryptorchidism because the testicle usually descends to the correct location by six months of age.11,26 | C | Systematic review, clinical practice guidelines |

| Imaging is not recommended before consultation with a surgical specialist.1,12,16,27,28 | C | Systematic review, clinical practice guidelines |

| Referral for surgical consultation is recommended by six months of age, or at the time of diagnosis in older patients.1,12,16 | C | Systematic review, clinical practice guidelines |

| Patients with a history of cryptorchidism can be taught how to perform monthly self-examinations for early detection of testicular cancer.1,12,14 | C | Clinical practice guidelines |

Normal Anatomy and Development

Testicular development and descent involve several key stages. Gonadal development originates within a pair of longitudinal ridges called the gonadal ridges. Testicles are primarily composed of mesenchymal tissue and are adjacent to the mesonephros epithelium. Failure of the primordial germ cells to migrate into these ridges leads to gonadal agenesis. Typical gonadal differentiation begins at approximately 5.5 weeks of gestation via the SRY gene, which triggers production of testis-determining factor protein. This protein leads to the differentiation of the primordial gonad into a testicle.4,5

The testicles then migrate from the gonadal ridge to the lumbosacral region near the developing kidneys in the abdominal cavity. Finally, they descend to their destination in the lower half of the scrotum. This occurs in two phases: a transabdominal phase from 8 to 15 weeks of gestation and an inguinoscrotal phase from 25 to 35 weeks of gestation. In the first phase, the testicles migrate to the inguinal ring by the regression of the cranial suspensory ligament. This occurs via testosterone signaling and reorganization of the caudal genitoinguinal ligament by the Leydig cell hormone insulin-like peptide 3. The second phase is driven by androgens and involves concurrent elongation of the processus vaginalis and caudal genitoinguinal ligament from the abdominal inguinal wall to the scrotum. This allows the testicles to migrate to the scrotum. The process is normally complete by 35 weeks of gestation.6–8

Classification

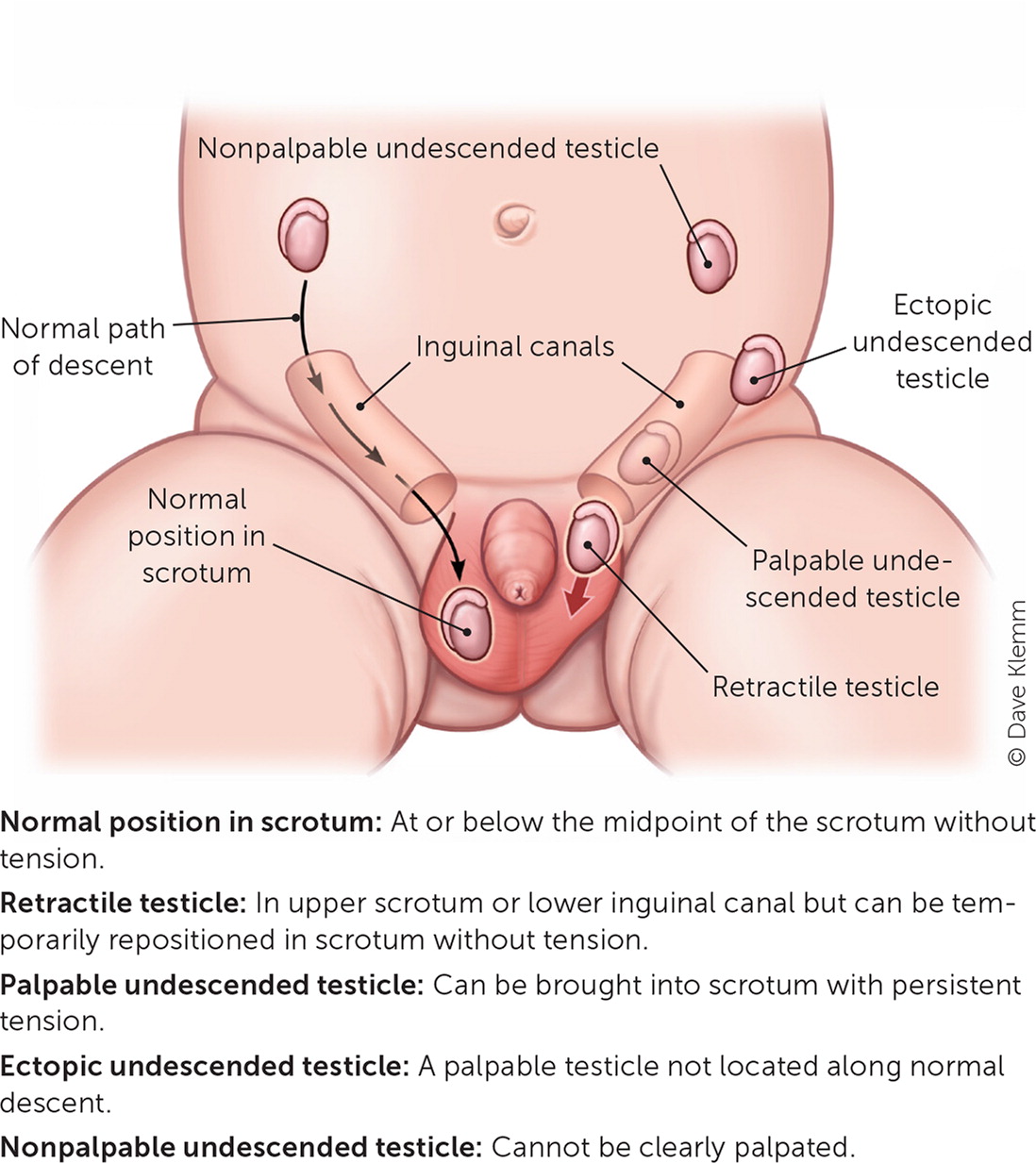

It is important to identify whether cryptorchidism presents as a palpable or nonpalpable testicle because each type has distinct evaluation and management recommendations. Nonpalpable testicles are less common and may present as completely absent or in a location that is not clearly appreciated on clinical examination. Palpable testicles are noted in approximately 80% of cryptorchidism cases.1,9,10 The four types of palpable testicles are retractile, undescended, acquired undescended, and ectopic undescended (Table 1).1,11

| Type | Location | Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Retractile | Upper scrotum or lower inguinal canal | Can be maintained within the scrotum with tension Intermittently positioned within the groin |

| Undescended | Not in the scrotum, at least halfway below its midpoint | Can be moved into the upper scrotum but requires constant tension to remain in this position; immediately retracts after release |

| Acquired undescended | Not in the scrotum, at least halfway below its midpoint | Also known as ascended testicle Was previously noted as palpable and in the correct position |

| Ectopic undescended | Not in the line of embryologic descent | Distal to the external inguinal ring Most commonly located in the superficial inguinal pouch Rarely found in the contralateral scrotum or prepubic, femoral, or perianal areas |

Evaluation

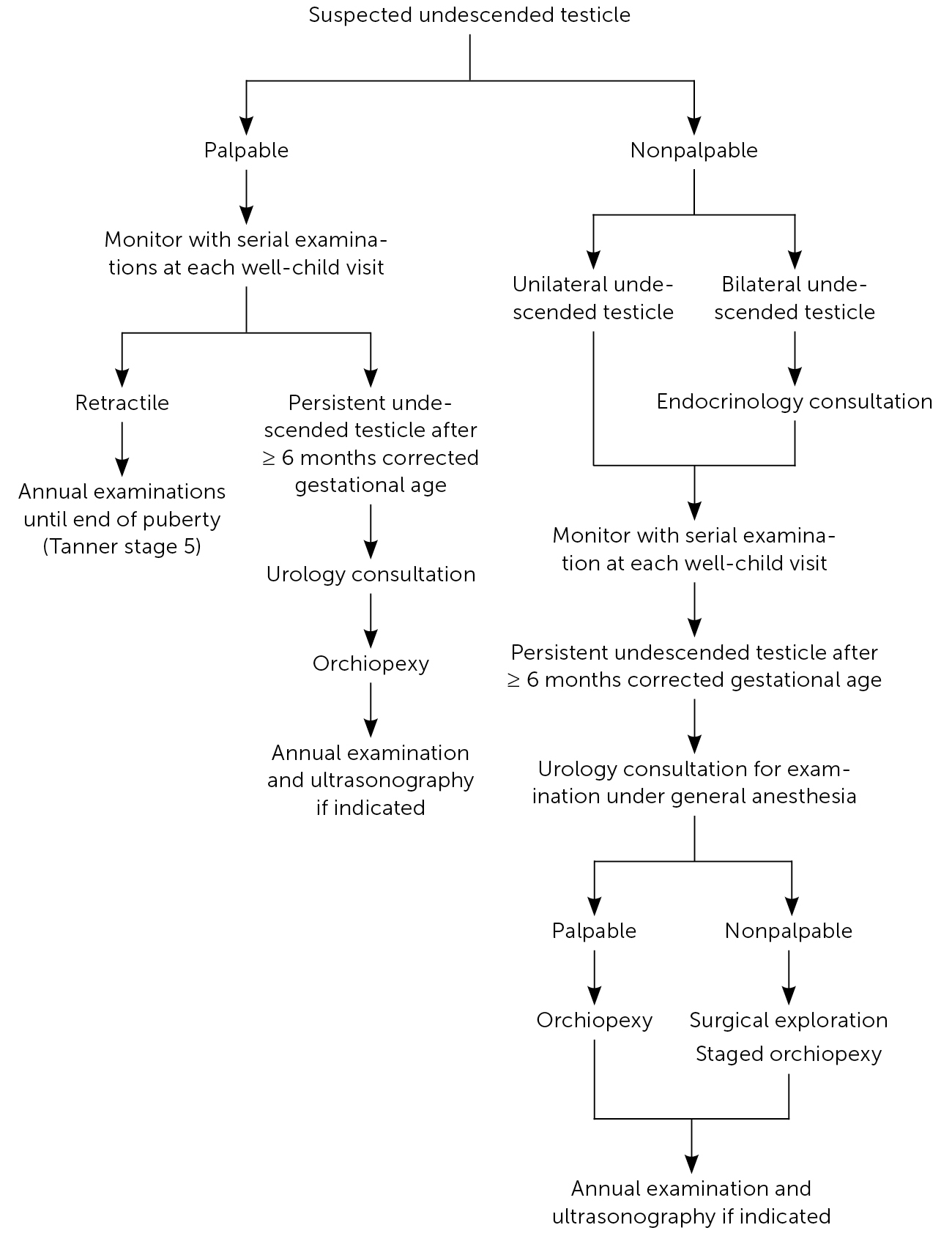

In 2018, the American Urological Association reaffirmed its 2014 clinical practice guidelines on the evaluation and management of infants with cryptorchidism. These and other clinical practice guidelines are summarized in Table 2.1,12–16 An approach to the evaluation and management of cryptorchidism is provided in Figure 1.1,9,12,16–18 [corrected]

| Recommendation/outcome | American Urological Association | British Association of Paediatric Surgeons/British Association of Urological Surgeons | Canadian Urological Association/Pediatric Urologists of Canada | European Association of Urology/European Society for Paediatric Urology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluation | ||||

| Consider gestational history | Yes | Not discussed | Yes | Yes |

| Routinely evaluate testicles until 6 months of corrected gestational age | At every well-child visit | Yes | At every monitoring infant visit | Not discussed |

| Evaluate and monitor retractile testicle | Annually | Not discussed | Every 6 to 12 months | Annually until end of puberty |

| Use endocrinologic evaluation for bilateral undescended testicles | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Refer for surgical consultation | If no descent by 6 months corrected gestational age or newly diagnosed after 6 months corrected gestational age | If no descent by 3 to 6 months corrected gestational age | If no descent by 6 months corrected gestational age or newly diagnosed after 6 months corrected gestational age | If no descent by 6 months corrected gestational age or newly diagnosed after 6 months corrected gestational age |

| Perform diagnostic imaging | No | No | No | No |

| Evaluate patient under anesthesia | For nonpalpable undescended testicle | Not discussed | For nonpalpable undescended testicle | For nonpalpable undescended testicle |

| Perform diagnostic surgical exploration for nonpalpable undescended testicle | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Treatment | ||||

| Hormone treatment | No | Not discussed | No | No |

| Orchiopexy (recommended age) | After 6 months corrected gestational age; 18 months at latest | 6 to 18 months | 6 to 18 months | 6 to 12 months if younger than 12 months; 18 months at latest |

| For palpable undescended testicle | Primary, inguinal, or scrotal orchiopexy | Orchiopexy (not specified) | Inguinal or scrotal orchiopexy | Standard orchiopexy |

| For nonpalpable undescended testicle | Primary or one-stage or two-stage Fowler-Stephens orchiopexy | Orchiopexy (not specified) | Primary or Fowler-Stephens orchiopexy | Laparoscopic, inguinal, or staged Fowler-Stephens orchiopexy |

| For postpubertal undescended testicle | Orchiectomy | Not discussed | Orchiectomy | Orchiectomy |

| Outcomes | ||||

| Fertility | Decreased fertility with bilateral undescended testicle | Not discussed | Decreased paternity with bilateral undescended testicles | Lower fertility and paternity with bilateral undescended testicles |

| Testicular cancer | Increased risk with intra-abdominal undescended testicle; risk decreased if orchiopexy performed before puberty | Not discussed | Slightly increased risk; risk decreased if orchiopexy done before puberty | Increased risk; risk decreased if managed before puberty |

| Self-examination to detect cancer | Monthly | Not discussed | Periodic | Monthly |

HISTORY

Because approximately 70% to 80% of undescended testicles are palpable, cryptorchidism is typically diagnosed through history and clinical examination.19 The history should include risk factors present before birth, family history of cryptorchidism, and a complete birth history including gestational age and birth weight.

CLINICAL EXAMINATION

Evaluation for cryptorchidism should be done during the newborn physical examination and at routine well-child examinations. Use of imaging studies for screening is not recommended. The evaluation should begin with the infant in the supine position. The scrotum and inguinal canal should be palpated with gentle to firm pressure to locate the testicles and evaluate for any other abnormalities such as hernia or hydrocele. The testicles should be oval-shaped and easily mobile within the scrotum.20 If a testicle is located outside the scrotum, it is important to determine whether it is palpable. The physician should palpate the entire path of descent to identify the location of the undescended testicle.21 Figure 2 illustrates possible sites of an undescended testicle; ectopic testicles may be found in other sites.11

Serial clinical evaluation is recommended to assess for changes in testicular position. A study in the United Kingdom noted a 50% decrease in the incidence of cryptorchidism from birth to three months of age.22 This is likely a reflection of spontaneous testicular descent within six months of corrected gestational age.23,24 But, the testicles can also ascend from the scrotum, leading to acquired cryptorchidism.22 Newer studies have reported the prevalence of acquired crypt-orchidism in children older than six years to be approximately 1% to 2%.25 Therefore, a thorough testicular examination should occur at the newborn visit and the well-child visits at two, four, and six months of age. Patients with retractile testicles should have annual examinations until puberty, when the testicular size and volume prevent retraction. More than 75% of retractile testicle cases resolve spontaneously.11,26

Infants with bilateral nonpalpable testicles should undergo further evaluation for disorders of sexual development. The risk of these disorders increases in the presence of additional congenital anomalies, including hypospadias, micropenis, and ambiguous genitalia. Further evaluation should also include assessment for congenital adrenal hyperplasia in male infants and female infants with virilization, and congenital anorchia and disorders of sexual development in male infants with undervirilization. Endocrinology consultation is recommended for further evaluation.12

DIAGNOSTIC IMAGING

Imaging results do not alter management recommendations per American Urological Association clinical guidelines. Imaging, including scrotal ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging, is not recommended before consultation with a surgical specialist, even in cases of nonpalpable testicles.1,12,16,27,28 Although ultrasonography is noninvasive and does not expose the child to radiation, it has a low sensitivity in determining the location of the testicles.12,28 Computed tomography is an expensive modality that does not yield clinically significant information beyond the physical examination, and it unnecessarily exposes the child to radiation.12,18,27 Magnetic resonance imaging is expensive, not readily available, and usually requires sedation to obtain adequate high-resolution images.

Treatment

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Orchiopexy (surgical manipulation of the testicle to relocate it to the proper position within the scrotum) is the primary inter vention for cryptorchidism. If spontaneous testicular descent has not occurred by six months of corrected gestational age, the patient should be referred to a surgical specialist.1,12,16 It is unlikely that an undescended testicle will undergo spontaneous descent after six months of age.12 Surgical intervention within the first 18 months of life is recommended to improve future fertility.12 Furthermore, testicular growth and fertility dramatically improve with surgical intervention before 12 months of age.29

HORMONAL MANAGEMENT

Although testicular descent is driven by hormona l signaling, use of human chorionic gonadotropin or luteinizing hormone–releasing hormone to induce descent is not recommended.12 The effectiveness of hormone treatment for the initial management of cryptorchidism is not well established and should be considered only when surgical management is contraindicated.12 It is also unclear whether hormone treatment can improve fertility.12

Outcomes and Counseling

Although the surgical specialist should perform close follow-up with the patient, the primary care physician has an important role in coordinating continued care and providing a point of reference for the patient and family.

FERTILITY POTENTIAL

Patients with a history of bilateral cryptorchidism have a sixfold increased risk of infertility, compared with the 1% to 2% prevalence of infertility in men not affected by cryptorchidism. A history of unilateral cryptorchidism does not seem to affect paternity rates.12 Location of the undescended testicle also does not appear to be a major factor in risk of infertility.30

TESTICULAR CANCER RISK

The risk of testicular cancer for patients with a history of cryptorchidism is approximately 3%, which is 5 to 10 times greater than that of the general population.31,32 Early surgical intervention reduces the risk of malignancy.33 When patients receive surgical intervention before 13 years of age, the risk is reduced to 2%. Patients who undergo orchiopexy after 13 years of age, or who do not receive surgical treatment, have approximately a 5% risk of testicular cancer.31

SELF-EXAMINATION

Patients with retractile testicles have an increased risk of acquired undescended testicles.34 It is estimated that more than 30% of retractile testicles become acquired undescended testicles, and this occurs most commonly in patients younger than seven years.35,36 Patients and families can be educated on the importance of close monitoring through early childhood and how to perform an examination at home.36

Self-examination can potentially identify early cancer. According to expert opinion, monthly self-examinations, especially after puberty, should be emphasized.12 An application from the Testicular Cancer Society demonstrates proper technique (https://testicularcancersociety.org/pages/self-exam-how-to).

SURVEILLANCE AFTER ORCHIOPEXY

Complications after orchiopexy are rare, occurring in less than 1% of cases.9 Injury to the ilioinguinal nerve or vas deferens is possible. Late complications include testicular atrophy, retraction (acquired undescended testicle), or torsion. Therefore, it is important for the patient to receive annual clinical examinations and ultrasonography to measure testicular volume and determine the testicular atrophy index. Depending on these results, hormonal testing, semen analysis, and testicular biopsy may be needed (Table 39,17,18). The results of biopsy may guide clinical recommendations for surgical removal of the testicle (orchiectomy).9,36

| Testicular atrophy index on ultrasonography | Laboratory tests | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 0% to 24% | FSH/LH level, testosterone level, and semen analysis | Repeat ultrasonography and laboratory tests every 12 months until patient is 18 years of age |

| 25% to 49% | FSH/LH level, testosterone level, semen analysis, and testicular biopsy | Repeat ultrasonography and laboratory tests every 12 months until patient is 18 years of age If the biopsy demonstrates atrophy or dysgenesis, orchiectomy is recommended regardless of age |

| ≥ 50% | Biopsy of the diminished testicle | If the biopsy demonstrates atrophy or dysgenesis, orchiectomy is recommended regardless of age |

Although several practice guidelines recommend surveillance with annual clinical examinations and ultrasonography, this is based on expert consensus rather than patient-oriented evidence. Thus, shared decision-making among the patient, family, and urologist should be used to determine the need for and type of follow-up.

This article updates a previous article on this topic by Docimo, et al.37

Data Sources: A PubMed search was completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms cryptorchidism and undescended testes. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Effective Health Care Reports, the Cochrane database, UpToDate, and Essential Evidence Plus were also searched. Whenever possible, if studies used race and/or gender as patient categories but did not define how these categories were assigned, they were not included in our final review. If studies that used these categories were determined to be essential and therefore included, limitations were explicitly stated in the manuscript. Search dates: December 18, 2022, and August 8, 2023.