Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(4):370-377

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

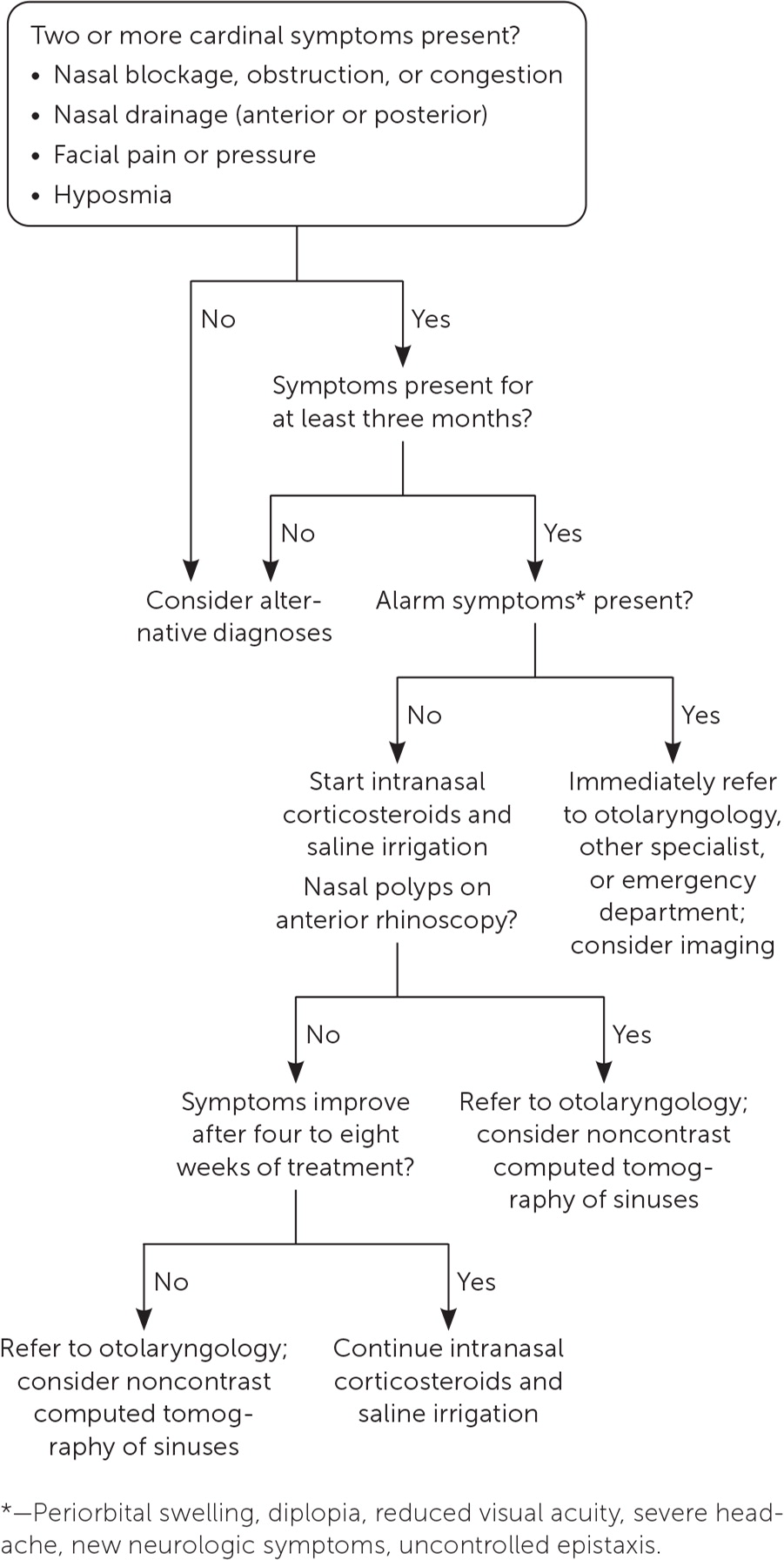

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is an inflammatory disease of the nose and paranasal sinuses, with a prevalence of approximately 1% to 7%. It is defined by the presence of at least two cardinal symptoms (nasal blockage, obstruction, or congestion; anterior or posterior nasal drainage; facial pain or pressure; and hyposmia) for at least three consecutive months, with objective findings on imaging or nasal endoscopy. CRS can result in significant patient costs and lower quality of life due to severe fatigue, depression, and sometimes reduced cognitive function. The condition is categorized as primary or secondary and with or without nasal polyps. Treatment is directed at reducing symptoms, improving mucus clearance, reducing inflammation, enhancing ciliary function, and removing bacteria and biofilms from the nasal mucosa. First-line treatment comprises nasal saline irrigation and intranasal corticosteroids. Acute exacerbation of CRS is common and is defined as a transient worsening of symptoms. The role of oral antibiotics and oral corticosteroids for acute exacerbations is unclear. Optimal maintenance therapy can help alleviate exacerbations. Patients with refractory CRS that is not responsive to first-line treatment and patients with alarm symptoms should be referred to an otolaryngologist for further evaluation and consideration of surgical management. Identifying patients who have CRS with nasal polyps or comorbid conditions such as atopic dermatitis, asthma, or eosinophilic esophagitis is especially important to ensure they are referred to a specialist for consideration of biologic therapy.

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is defined as at least three continuous months of inflammation of the nose and paranasal sinuses leading to both sinonasal and extranasal symptoms.1 Childhood CRS is a distinct condition; this article only covers adult CRS.

Epidemiology

The estimated prevalence of CRS ranges from 5.5% to 16% globally, but this could be overestimated due to significant symptom overlap with other disease processes.2 Two studies, one from Europe and one from the United States, used imaging and diagnostic criteria to estimate the prevalence of CRS at 3% to 6.4% and 1.6% to 7.5%, respectively.3,4 The estimated annual impact of this disease on the U.S. health care system is $8.6 billion in direct costs, with individual patients spending an average of $1,605.5,6

Quality-of-Life Impacts

In a study evaluating the health status of patients using the Short-Form Six-Dimension instrument, patients with CRS reported worse health states than patients with congestive heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or Parkinson disease.7 Extranasal symptoms have the greatest negative effect on overall quality of life and include fatigue, body pain, sleep dysfunction, cognitive issues, and depression.8–14 Due to the severity of these symptoms, they should be evaluated and used to monitor quality of life.

Pathology and Associated Conditions

CRS can be primary or secondary. Primary CRS is further categorized based on the immunologic pathways driving the condition (i.e., type 2 or non–type 2 inflammation). Type 2 CRS is more often associated with polyps, adult-onset asthma, and allergic diseases. Eosinophil and immunoglobulin E counts can be high in type 2 CRS, and these mediators are the targets of biologic therapy.15 Non–type 2 CRS also includes noneosinophilic CRS.1,16,17

Secondary CRS is caused by local pathologies, such as odontogenic infection, sinus fungal ball, or more systemic pathologies, including immunodeficiencies, diseases with poor mucociliary clearance (e.g., cystic fibrosis, primary ciliary dyskinesia), and autoimmune diseases (e.g., granulomatosis with polyangiitis).

The triad of nasal polyps, asthma, and respiratory reactions caused by cyclooxygenase-1 enzyme inhibitors is a distinct category of CRS and represents aspirin-exacerbated respiratory disease, for which a protocol of aspirin desensitization is recommended along with symptom-driven treatments.17

The disease is also categorized as CRS with nasal polyps or without polyps.1 For treatment purposes, this categorization is most applicable in the primary care setting.

Diagnosis

| Must meet patient-reported criteria and objective criteria |

| Patient-reported criteria (three or more continuous months of at least two of the four cardinal symptoms): |

| Nasal blockage, obstruction, or congestion |

| Nasal drainage (anterior or posterior) |

| Facial pain or pressure |

| Hyposmia |

| Objective criteria (either or both of the two constellations of findings listed below): |

| Endoscopy: Nasal polyps, mucopurulent discharge from sinus outflow, edema, or mucosal obstruction from sinus outflow |

| Computed tomography: Mucosal thickening/opacification in ostiomeatal complex or paranasal sinuses |

MEDICAL HISTORY

The four cardinal symptoms of CRS are nasal blockage, obstruction, or congestion; anterior or posterior nasal drain-age; facial pain or pressure; and hyposmia. At least two of the four symptoms for a minimum of three consecutive months are required for diagnosis.1

| Condition | Presentation | Condition | Presentation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute bacterial rhinosinusitis | Symptoms for less than four weeks, facial pain or pressure, purulent nasal drainage, nasal obstruction or congestion, hyposmia or anosmia | Irritant rhinitis | Rhinorrhea or nasal congestion triggered by exposure to an irritant |

| Rhinitis medicamentosa | Rebound congestion and rhinorrhea after cessation of intranasal decongestants, or from recurrent cocaine use | ||

| Autonomic rhinitis | Rhinorrhea or sneezing triggered by physical, emotional, or gustatory stimuli | Nasal foreign body | Unilateral nasal obstruction, rhinorrhea, facial pain or pressure; often occurs in children |

| Allergic rhinitis | Rhinorrhea, nasal obstruction, sneezing, nasal or ocular pruritus | Obstructive sleep apnea | Facial pressure, nasal obstruction, chronic fatigue, snoring |

| Benign or malignant sinonasal neoplasm | Unilateral facial pain or pressure and rhinorrhea, severe headache, uncontrolled epistaxis | Odontogenic sinusitis abscess | Unilateral facial pain and swelling, dental pain, nasal drainage, nasal obstruction, hyposmia or anosmia |

| Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea | Unilateral clear rhinorrhea, metallic or salty taste of discharge, neurologic symptoms; history of trauma, surgery, or idiopathic intracranial hypertension is also an indicator | Orbital cellulitis | Unilateral facial pain, eye swelling, diplopia, decreased visual acuity, pain with eye movement |

| Hormonal rhinitis | Swollen nasal membranes, congestion or rhinorrhea due to hormonal changes (e.g., during pregnancy, menstruation, or use of oral contraception) | Primary headache disorder (tension headache, migraine, cluster headache) | Facial pain or pressure, rhinorrhea |

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

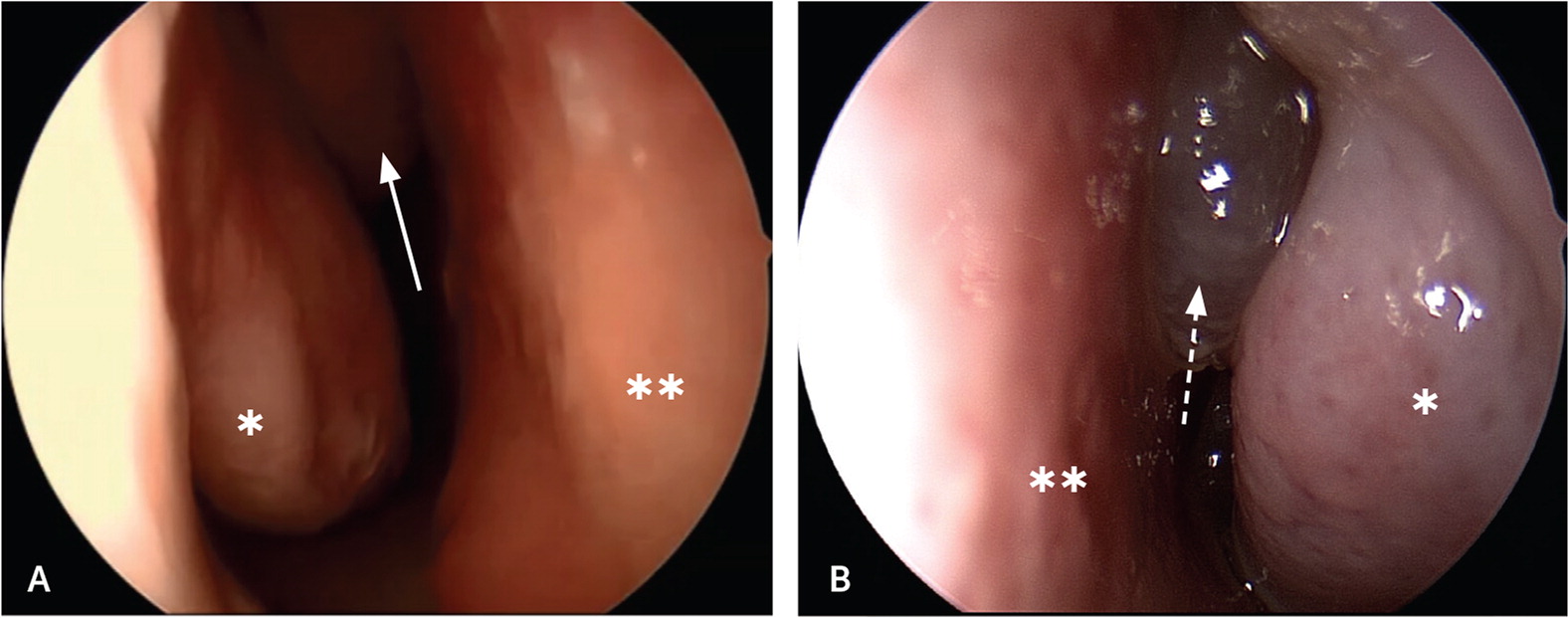

Physical examination includes sinus palpation and oropharyngeal assessment. Most importantly, anterior rhinoscopy should be performed using a nasal speculum (or otoscope speculum) and headlight to look for polyps and mucopurulent drainage (Figure 219). Patients with polyps or alarm symptoms should be referred to otolaryngology for nasal endoscopy.

IMAGING

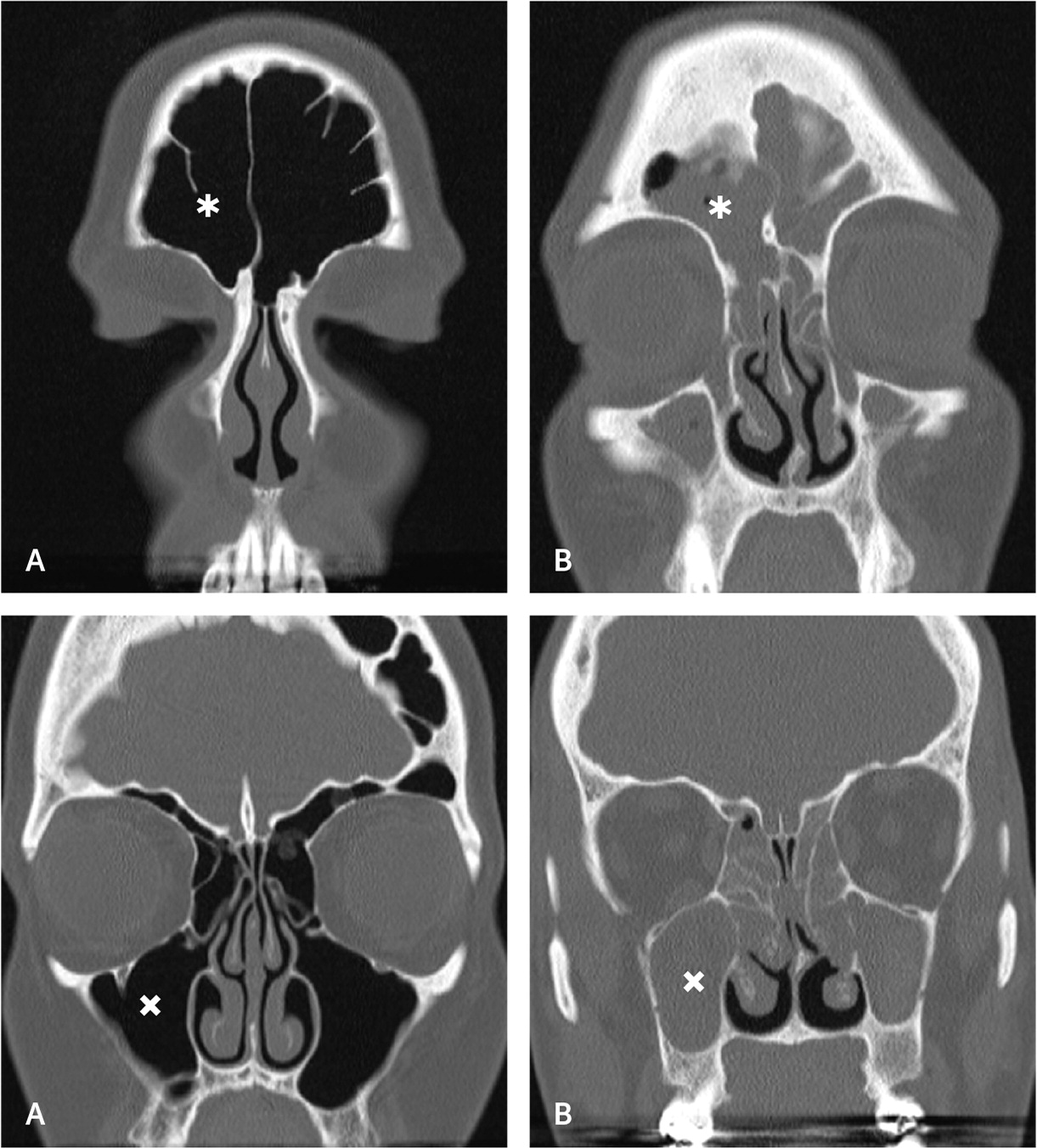

Radiography of the face or sinuses is generally not recommended.8,18,20,21 Nonspecific inflammation of the sinus mucosa is often the only computed tomography (CT) finding of CRS. Noncontrast CT (Figure 319) is recommended to rule out alternative diagnoses, especially for patients with unilateral symptoms.8,21 If patient-reported diagnostic criteria are met, nasal endoscopy is not readily available, and the patient does not improve with four to eight weeks of first-line therapy, noncontrast CT of the sinuses may be considered to confirm the diagnosis of CRS. The American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation advises against ordering sinus CT within 90 days of a previous CT scan for uncomplicated CRS22 (Table 320–23).

| Recommendation | Reasoning | Organization |

|---|---|---|

| Do not order more than one CT scan of the paranasal sinuses within 90 days to evaluate patients with uncomplicated chronic rhinosinusitis when the paranasal sinus CT scan obtained is of adequate quality and resolution to be interpreted by the clinician and used for clinical decision-making or surgical planning. | CT is expensive, exposes the patient to ionizing radiation, and offers no additional information that would improve initial management. Multiple CT scans within 90 days may be appropriate in patients with complicated sinusitis or when an alternative diagnosis is suspected. | American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery |

| Do not order plain sinus radiography. | Plain radiography has poor sensitivity and specificity and cannot be relied on to confirm or reject the diagnosis of acute or chronic sinusitis. Findings such as air-fluid levels and complete sinus opacification are not reliably present in rhinosinusitis and cannot differentiate between viral and bacterial etiologies. The complex anatomy of the ethmoid sinuses and critical sinus drainage pathways are not delineated effectively with plain radiography and are inadequate for operative planning. Because findings on plain sinus radiographs cannot be relied on to diagnose rhinosinusitis, guide antibiotic prescribing, or plan surgery, they do not provide value in patient care and should be avoided. | Canadian Society of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery |

Treatment

Numerous treatment options can improve quality of life in patients with CRS. A validated patient-reported outcome measure, such as the Sino-Nasal Outcome Test (https://www.virginiaallergyrelief.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/sino_nasal-1.pdf), can help evaluate the effect of symptoms on quality of life and monitor treatment response. Higher scores suggest worse symptoms and potentially greater benefit from treatments such as surgery and biologics.1,24 In addition to improvement in quality of life, the more direct goals of treatment for CRS are to reduce symptoms, improve mucus clearance, reduce inflammation, enhance ciliary function, and remove bacteria and biofilms from the nasal mucosa.8 Table 4 highlights treatment options.1,8,25–52 CRS with nasal polyps should be managed by specialty physicians given the emergence of biologic therapy.

| Treatment | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Intranasal saline1,8,25,26 | First-line treatment |

| Larger volume is preferred | |

| Intranasal corticosteroids1,8,27–31 | First-line treatment |

| Long-term use is safe | |

| Epistaxis is an adverse effect | |

| Biologic therapy 32–37 | Mainstay of treatment in patients with polyps if they have not improved with first-line medical and surgical therapy or have comorbid conditions such as asthma, atopic dermatitis, or eosinophilic esophagitis |

| Oral corticosteroids38–42 | Should generally be avoided; can be considered in select patients with acute exacerbations or severe CRS after taking into account adverse effects |

| Oral antileukotrienes43,44 | Can be considered as adjunct therapy in patients with an allergic component or polyps |

| Oral antihistamines45 | Can be considered as adjunct therapy in patients with an allergic component, although evidence is less supportive than that for antileukotrienes |

| Oral antibiotics1,8,46–48 | Long-term use (for more than three weeks) of macrolide antibiotics can be considered for symptom relief; antibiotics have been shown to improve endoscopic findings, but the clinical significance of this is unclear |

| Short-term oral antibiotics are not recommended for CRS or acute exacerbations of CRS due to the lack of effectiveness | |

| Nasal decongestants49 | Not recommended due to lack of benefit and potential harm |

| Alternative therapies8,50–52 | Xylitol and topical capsaicin may have benefit in some patients |

INTRANASAL SALINE

Consensus guidelines reaffirm the use of intra-nasal saline sprays or irrigation for CRS without nasal polyps to improve quality of life and endoscopic findings.1,8 Irrigation is more effective than sprays, and irrigations of more than 60 mL are favored due to improved mucus clearance.25,26 Irrigation achieves maximum benefit compared with placebo after eight weeks and can be delivered via a variety of devices, from bulb suction to large-volume pots.8 Hypertonic saline has been shown to be more effective than isotonic saline but can be more irritating and therefore is generally not recommended.1,26

INTRANASAL CORTICOSTEROIDS

Intranasal corticosteroids are commonly prescribed for CRS and are considered first-line therapy.1,8 Evidence also supports use of intranasal corticosteroids for improvement in quality of life.27–30 Although consensus guidelines make no formal recommendation on the duration of treatment, most studies examined treatment periods of 12 to 20 weeks.28 Long-term use of intranasal corticosteroids is safe with minimal adverse effects, although it may increase risk of epistaxis.31

The intranasal corticosteroid spray should be administered with the patient’s head in the upright position and after they blow their nose. The spray should be aimed away from the nasal septum to reduce the risk of epistaxis, and the patient should gently breathe in with administration.1

ORAL ANTIHISTAMINES

Few studies have examined oral antihistamines for the treatment of CRS, and their use is not recommended. Oral antihistamines can be considered as an adjunct treatment if the patient has concomitant allergic rhinitis.45

ANTILEUKOTRIENE THERAPY

ANTIBIOTICS

The benefit of oral antibiotics for CRS is unclear. A 2016 Cochrane review found conflicting results, with no demonstrable benefit in most trials.8,46 Long-term use (more than three weeks) of macrolide antibiotics has shown benefit for select patients with CRS who are at low risk of medication adverse effects.8,47 Only low-quality evidence supports using shorter courses of macrolides or other antibiotics for CRS, therefore they are not recommended.1,48

NASAL DECONGESTANTS

Topical and oral decongestants are not recommended for CRS. Patients often report temporary symptom improvement with topical decongestants, such as oxymetazoline, but these medications have not been proven effective. The potential for rebound congestion (rhinitis medicamentosa) is high with long-term use of these medications.49

ORAL CORTICOSTEROIDS

Oral corticosteroids are often prescribed for CRS and have been shown to improve symptoms and imaging findings, especially if polyps are present.38,39 Benefits are generally brief, with little improvement in long-term outcomes.40,41 There is only very low-quality evidence supporting use of oral corticosteroids for CRS without polyps. Short-term use (10 to 14 days) is an option given the potential benefit, especially for patients with more severe symptoms, with careful consideration of the medication’s well-known adverse effects and patient preferences and comorbidities.8,42,53

HERBAL AND ALTERNATIVE TOPICAL THERAPIES

Several herbal and alternative topical therapies have been suggested for treatment of CRS. One small randomized controlled trial showed that nasal irrigation with xylitol, a sugar alcohol with natural antibacterial properties, is superior to saline irrigation for symptom relief in postsurgical patients.50 Topical capsaicin has shown benefit in the treatment of CRS with nasal polyps and can be used as an adjunct therapy.51 It should be noted that major international guidelines do not include formal recommendations for herbal therapies due to lack of evidence.8

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Endoscopic sinus surgery is the recommended surgical option if CRS does not improve with medical management. This is defined as continued symptoms and objective findings on endoscopy or imaging despite appropriate medical therapy.54 Referral for surgical evaluation should be considered after a minimum of three to four weeks, preferably at least eight weeks, of nasal irrigation and intranasal corticosteroids.8 The goals of surgery are to reduce symptoms and improve mucosal drainage by opening sinus drainage pathways and allowing for enhanced delivery of topical therapies.8,55

BIOLOGICS

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recently approved the following biologic drugs for CRS with nasal polyps: dupilumab (Dupixent), omalizumab (Xolair), and mepolizumab (Nucala).33–37 Each of these medications also has FDA approval for comorbid conditions that often occur in patients with CRS. Dupilumab is approved for the treatment of atopic dermatitis, moderate to severe asthma, eosinophilic esophagitis, and prurigo nodularis.33 Omalizumab is approved for moderate to severe asthma and chronic spontaneous urticaria.35 Mepolizumab is approved for severe asthma, eosinophilic granulomatosis with polyangiitis, and hypereosinophilic syndrome.34 A fourth biologic, benralizumab (Fasenra), is FDA-approved only for severe eosinophilic asthma but has shown promise in phase 3 trials for patients with CRS with nasal polyps.37

Acute Exacerbations

Acute exacerbation of CRS (i.e., transient worsening of symptoms that often improves after some intervention) is common. Exacerbations are often associated with infection and are more likely to occur if CRS is not optimally managed.18

Although antibiotics are commonly prescribed for these exacerbations, only low-quality evidence supports this practice. Expert guidelines make no recommendation on the issue due to a lack of evidence. This is a notable change from prior guidelines, which recommended the use of antibiotics for acute exacerbations.1,8 Oral corticosteroids are also commonly prescribed for exacerbations, but supportive evidence is lacking. Oral corticosteroids have been shown to reduce polyp size and symptoms during acute exacerbations. Given the lack of proven effectiveness of these approaches, the mainstay of treatment remains intranasal saline and intra-nasal corticosteroids to control CRS and prevent exacerbations.56

Data Sources: The manuscript was based on literature identified in Cochrane reviews (chronic rhinosinusitis) and PubMed clinical queries (search words: rhinosinusitis, sinusitis, chronic sinusitis, chronic rhinosinusitis, chronic frontal sinusitis, chronic maxillary sinusitis, chronic ethmoid sinusitis). References from those sources were also searched. Guidelines were accessed and referenced through European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps (EPOS 2020),1 International Consensus Statement on Allergy and Rhinology: Rhinosinusitis (ICAR-RS 2021),8 and the American Academy of Otolaryngology Clinical Practice Guidelines on Adult Sinusitis.18 Search dates: August 23, 2022, and August 8, 2023.