Update: In September 2025, the US Food and Drug Administration alerted physicians about initiating a process for label changes for acetaminophen use in pregnancy due to associations with neurodevelopmental disorders. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists reaffirmed its position on the safety and benefits of moderate acetaminophen use in pregnancy given the lack of association with autism, ADHD, and intellectual disability in a large cohort study, and the lack of safe alternatives.

This is a corrected version of the article that appeared in print.

Am Fam Physician. 2023;108(4):360-369

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

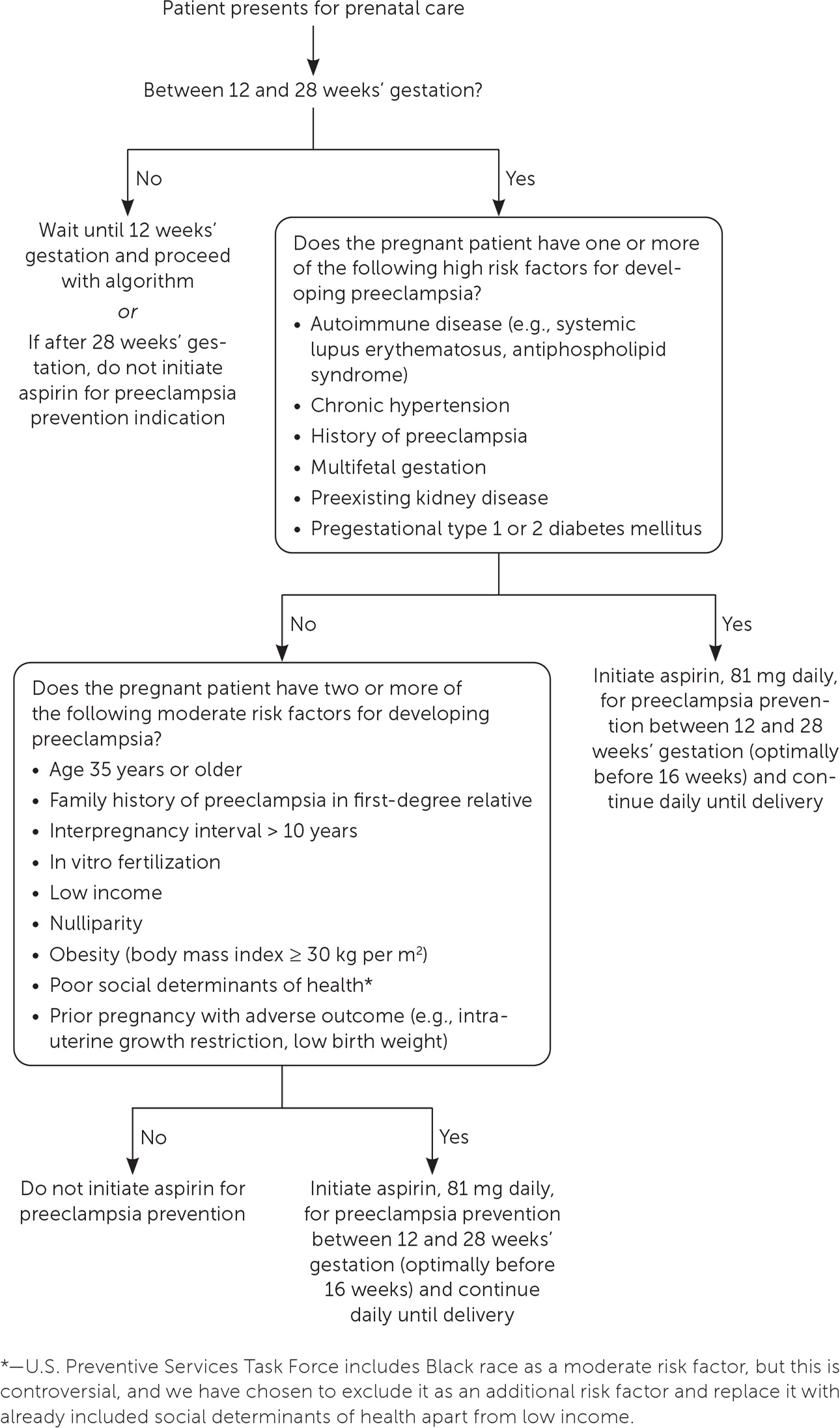

High-quality research on the safety and effectiveness of over-the-counter medications in pregnancy is limited. Physicians should explore nonpharmacologic treatments before recommending medication. For nausea and vomiting in pregnancy, vitamin B6 (pyridoxine), H1 antihistamines, and ginger are safe and effective. Physicians can recommend calcium carbonate, H2 antihistamines, and proton pump inhibitors for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Osmotic laxatives, fiber preparations, and probiotics are safe and effective treatments for constipation. Many over-the-counter topical medications are safe in pregnancy due to low systemic absorption, but topical retinoids, such as adapalene, should be avoided. Hypertonic saline nasal rinse and antihistamines are safe, beneficial options for treating pregnancy-induced rhinitis, and intranasal corticosteroids have demonstrated benefit for chronic allergic rhinitis. The safety of acetaminophen for the treatment of headaches and low back pain during pregnancy has come into question with recent studies; therefore, judicious use is advised. Physicians should screen all pregnant patients for their risk of developing preeclampsia and initiate low-dose aspirin from 12 weeks’ gestation until delivery for those at increased risk. Data are limited on the safety and effectiveness of herbal supplements during pregnancy.

Prenatal care necessitates balancing the benefits and harms of treatment for the pregnant patient and developing fetus. Few randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of over-the-counter (OTC) medications in pregnancy exist; therefore, data on safety and effectiveness primarily come from case-control and cohort studies. Because of limited high-quality evidence, physicians should guide patients to use OTC medications that are considered safe at the lowest effective dose and duration necessary to bring relief. For mild symptoms and self-limited conditions, nonpharmacologic therapies should be encouraged. When symptoms are moderate to severe, enduring, or pose a risk to the mother or fetus, physicians should select the safest effective medication available. This article reviews the safety and effectiveness of OTC medications for common conditions of pregnancy.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| First- and second-generation antihistamines are safe to use throughout pregnancy.4,5,11,12 | B | Consistent evidence from case-control studies, cohort studies, and observational data |

| Ginger, 1,000 to 1,500 mg daily, is safe and effective for the treatment of mild to moderate nausea and vomiting of pregnancy in the first trimester.6–9 | B | Consistent evidence from randomized controlled trials that show ginger reduces nausea but not always vomiting episodes |

| Acetaminophen should be used at the lowest effective dose and duration needed and with physician consultation.39 | C | Expert opinion based on cohort, case-control, and longitudinal studies showing acetaminophen exposure in pregnancy was associated with an increased risk of neurodevelopmental disorders and asthma in exposed offspring; there may be residual confounding and bias in these studies |

| Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be limited in the third trimester to scenarios in which benefits outweigh the risks due to an association with premature closure of the ductus arteriosus.43,44 | B | Meta-analysis of small randomized controlled trials with consistent evidence for increased risk of ductus arteriosus constriction after exposure to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the third trimester |

| Initiate aspirin, 81 mg daily, at 12 to 28 weeks’ gestation in women who are at increased risk of preeclampsia.57–59 | A | Consistent evidence from randomized controlled trials showing significant risk reduction for perinatal mortality, preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, and risk of preeclampsia without increased risk of bleeding or premature ductus arteriosus closure |

In 2015, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration transitioned from its prior labeling system of categorizing drug safety with A, B, C, D, and X letter classifications to the new Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule. This new labeling scheme provides a narrative summary of risk, data, and clinical considerations for medications in pregnant and lactating women and those with reproductive potential.1,2 Medication adverse effects are more likely in the first and third trimesters. Organogenesis, occurring in the second through eighth week after conception, is a critical time for limiting medication exposure. In the third trimester, it is important to avoid medications that adversely affect the final stages of gestation and the newborn period.

Antiemetics

OTC medications are first-line treatment for nausea and vomiting in pregnancy.3 Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine) dosages of less than 100 mg daily are safe as initial treatment for nausea and vomiting in pregnancy. First-generation H1 antihistamines, such as doxylamine and diphenhydramine, can be used throughout pregnancy without an increased risk of spontaneous abortion, major malformations, premature birth, stillbirth, or low birth weight.4,5

Ginger is one of the most commonly used herbal medications in pregnancy, primarily taken for nausea and vomiting.6 First-trimester ginger use is not associated with major congenital malformations or spontaneous abortion.7,8 According to a 2014 meta-analysis of 12 RCTs that included 1,278 pregnant patients, ginger in a daily dosage of 1,000 to 1,500 mg administered in two to four divided doses is as effective as pyridoxine and superior to placebo for relief of mild to moderate nausea in early pregnancy.7–9 However, ginger use during the second and third trimesters has been associated with vaginal bleeding, premature birth, and reduced fetal head circumference.8

Antacids

Many OTC treatments for gastroesophageal reflux disease are available. Physicians can recommend calcium carbonate up to the usual dose limits as the preferred antacid in pregnancy.10 If calcium carbonate is ineffective at controlling symptoms, H2 antihistamines and proton pump inhibitors are safe options. Inadvertent use of H2 antihistamines and the results of several cohort studies have not shown an associated increase in major congenital malformations, low birth weight, or perinatal mortality.11 A 2020 meta-analysis concluded that there may be an increased risk of congenital malformations and asthma in children exposed to proton pump inhibitors in utero, but confounding, recall bias, and low power of the included studies preclude declaring a definite association.12 Sodium bicarbonate found in some antacid preparations can cause maternal or fetal fluid overload and metabolic alkalosis; therefore, patients should be cautioned to avoid this ingredient.10 Bismuth subsalicylate–containing products easily cross the placenta into fetal circulation and should be avoided after 20 weeks’ gestation due to the risk of fetal renal dysfunction, oligohydramnios, and premature closure of the ductus arteriosus.13

Constipation Treatments

Functional constipation is common in pregnancy. Increasing water and dietary fiber intake and incorporating light physical activity may relieve symptoms.14 Bulk-forming agents, such as psyllium husk, may reduce constipation. In patients taking iron, dosing every other day may help.14 Osmotic laxatives, including polyethylene glycol 3350 and magnesium hydroxide, are safe and effective in pregnancy; systemic absorption is minimal, but regular long-term use can lead to electrolyte imbalance.14 No adverse outcomes have been shown with the use of probiotics for stool regularity.15 One pilot study using multispecies probiotics showed increased stool frequency, improved stool consistency, and less anorectal obstruction sensation after two weeks of use, with sustained effects at four weeks. These results are consistent with RCTs among nonpregnant populations.16

Constipation may lead to hemorrhoids, especially in the second and third trimesters. Educating patients on dietary and stooling habits early in pregnancy has been shown to reduce hemorrhoids at delivery.17 If topical medications are needed, 1% hydrocortisone applied as a thin layer twice daily for up to 10 consecutive days is acceptable for use in the second and third trimesters.18 Limited data suggest safety for the use of lidocaine after the first trimester and pramoxine during the third trimester.19,20

Topical Medications

Acne may improve during the first trimester but worsen in the third trimester as androgen production increases. Nonpharmacologic treatments include avoiding oily cosmetics, facial cleansing twice daily, and reducing dairy and high glycemic index food intake.21 Topical benzoyl peroxide and azelaic acid are safe to use in pregnancy.21–23 Oral retinoids are known teratogens. Adapalene, an OTC topical retinoid, is not recommended during pregnancy because the evidence of benefit remains insufficient to outweigh potential fetal risk.24,25

Rashes, including eczema and tinea infections, may cause significant discomfort in pregnancy. In addition to nonpharmacologic measures, hydrocortisone 0.5% or 1% cream applied once or twice daily is safe to use for eczema-associated itching and inflammation.18 Prolonged use and higher potency corticosteroids may cause hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression and, rarely, hyperglycemia or hypertension.26 Tinea skin infections may be treated with a topical azole antifungal, such as 1% clotrimazole twice daily for two to four weeks.27 Table 1 summarizes OTC topical medications that are commonly used in pregnancy.13,18–20,22,26–29

| Medication class | Drug name | Bioavailability | Use | Effectiveness and timing | Risk |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acne agents13,22 | Azelaic acid, 15% to 20% | 3% to 10% | Mild to moderate acne vulgaris | Acceptable for use in any trimester Apply twice per day at maximum strength | No demonstrated teratogenicity |

| Benzoyl peroxide, 2.5% to 5% | Unknown | ||||

| Analgesic13 | Lidocaine, 4% to 5% patch, cream, or ointment | 1% to 3% | Musculoskeletal pain and arthritis | Use only if the potential maternal benefit outweighs the potential risk to the fetus | Lidocaine crosses the placenta; acceptable for use after the first trimester19 Acceptable for use in the third trimester20 |

| Pramoxine, 1% foam, cream, or ointment | Unknown | Hemorrhoid pain and pruritus | |||

| Azole antifungals13,27 | Clotrimazole, 1% solution, cream, or ointment Miconazole, 2% topical cream | Skin: < 0.5% | Dermatophyte infections: tinea corporis, tinea cruris, tinea pedis, Malassezia furfur Candida spp. | More effective than nystatin | Oral azole antifungals have teratogenic potential, making the lowest effective dose and duration and use after the first trimester reasonable27 |

| Corticosteroid13,18 | Hydrocortisone, 0.5% to 1% lotion, cream, or ointment | Varies with where applied and patient-specific factors | Atopic dermatitis Hemorrhoid pain and pruritus | Topical corticosteroids are first-line treatment for atopic dermatitis Low-potency, over-the-counter topical corticosteroids are acceptable for use throughout pregnancy No evidence of teratogenicity | Large cumulative doses of high-potency topical cortico-steroids show a probable association with low birth weight and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression, rare hypertension, and hyperglcyemia26 |

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs28,29 | Diclofenac, 1% to 3% solution or gel | 2% to 10% | Musculoskeletal pain and arthritis | Use only between 12 and 20 weeks’ gestation for conditions refractory to first-line therapies | Diclofenac crosses the placenta Possible embryotoxicity with first-trimester use Risk of fetal renal dysfunction and oligohydramnios with use after 20 weeks’ gestation Risk of premature closure of the ductus arteriosus with use after 30 weeks’ gestation |

| Retinoid22 | Adapalene (Differin) | Minimal | Acne | Not recommended for use in any trimester | Insufficient data to support safe use Major congenital abnormalities associated with oral retinoids |

Antihistamines and Decongestants

Pregnancy-induced rhinitis, allergic rhinitis, and respiratory viruses are common causes of nasal congestion in pregnancy.30 Hypertonic saline nasal rinse is safe and effective to reduce rhinitis symptoms in pregnant women.31 Intranasal or oral antihistamines can be safely recommended4,5 (Table 23–12,14–16,18–23,26,28–52). [corrected] Intranasal corticosteroids can benefit patients with chronic allergic rhinitis; their safety is supported by the extrapolation of safety data on inhaled corticosteroids for asthma in pregnancy and expert opinion.49 Intranasal corticosteroids have questionable benefit in pregnancy-induced or nonallergic rhinitis.30,50

| Condition or symptom | Incidence among pregnant patients | Nonpharmacologic treatments and lifestyle modifications | Over-the-counter treatments available and their use in pregnancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acne21–23 | Up to 43% Typically worsens in late pregnancy |

Avoid oily cosmetics Cleanse face twice daily Reduce dairy and high glycemic index food intake |

Azelaic acid: acceptable to use Adapalene (Differin): avoid use because of possible teratogenicity Benzoyl peroxide: acceptable to use |

| Constipation14 | 25% to 40% | Increase water intake (> 64 oz per day) Increase dietary fiber intake (> 20 to 35 g daily) Engage in light physical activity Reduce iron dosing to every other day when appropriate in those patients requiring iron therapy |

Bulk-forming agents (e.g., psyllium husk): acceptable to use Multispecies probiotics: acceptable to use; may be effective15,16 Osmotic laxative (e.g., polyethylene glycol 3350, magnesium hydroxide): acceptable to use, but prolonged use can cause electrolyte imbalance |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease10 | Approximately 30% to 50%, reaching 80% in some populations | Elevate head of bed or lie on left side Reduce or avoid trigger foods (e.g., fatty, spicy, citrus) Avoid lying down within three hours after eating |

Aluminum or magnesium antacids: acceptable to use; avoid magnesium trisilicate Bismuth subsalicylate: avoid use; similar risk as NSAIDs Calcium carbonate: preferred antacid H2 antihistamines (e.g., cimetidine, famotidine, nizatidine [Axid]): acceptable to use5,11,12,14 Proton pump inhibitors (e.g., esomeprazole, lansoprazole, omeprazole): acceptable to use in the second and third trimesters; possible increased risk of minor malformations12,14 Sodium bicarbonate: avoid use; can cause maternal or fetal fluid overload and metabolic alkalosis |

| Headache32 | Estimate 40% | — | Acetaminophen: acceptable to use; may increase risk of neurodevelopmental disorders and asthma33–39 Caffeine: acceptable for migraine treatment; less than 200 mg per day32,40 Magnesium oxide: acceptable for migraine prophylaxis; 400 to 800 mg per day41 NSAIDs: avoid use in the first trimester and after 20 weeks’ gestation42–44 |

| Hemorrhoids18 | 15% to 41%, reaching up to 85% in some populations | Take a sitz bath Increase water intake Increase fiber-rich foods Exercise or walk for 30 to 60 minutes three to five times per week Do not ignore the urge to defecate, spend less than three minutes on the commode, and attempt to defecate 30 to 40 minutes after each meal |

Low-potency topical corticosteroids (e.g., hydrocortisone 1%): acceptable to use18,26 Topical lidocaine: acceptable to use after the first trimester19 Topical pramoxine: acceptable to use in the third trimester 20 |

| Insomnia | Sleep disturbance: 66% to 97%45,46 | Improve sleep hygiene Exercise Limit caffeine intake Restrict fluid intake in the hours before sleep |

H1 antihistamines (e.g., diphenhydramine, doxylamine, hydroxyzine): acceptable to use4 Melatonin: probably safe but lacks adequate human data to recommend its use over antihistamines47 |

| Low back pain | Up to 68%48 | Stretch Participate in physical therapy or osteopathic manipulation therapy Use a heating pad (not applied to abdomen or pelvis) |

Acetaminophen: acceptable to use; may increase risk of neurodevelopmental disorders and asthma33–39 NSAIDs: avoid use in the first trimester and after 20 weeks’ gestation28,29,42–44 Topical lidocaine: acceptable to use after the first trimester19 |

| Nausea and vomiting3 | Nausea: 50% to 80% Vomiting: 50% |

Take prenatal vitamins one month before conception Dietary modifications: eat small, frequent meals and dry, bland foods Change prenatal vitamin to folic acid supplement |

Ginger: acceptable to use in the first trimester; increased risk of vaginal bleeding with use after 17 weeks’ gestation; 1,000 to 1,500 mg per day for four consecutive days6–9 H1 antihistamines: acceptable to use11,12; diphenhydramine, 25 to 50 mg every four to six hours, or doxylamine, 12.5 mg three to four times per day3 [corrected] Vitamin B6 (pyridoxine): safe to use; 10 to 25 mg three to four times per day9 [corrected] |

| Rhinitis5,30,31,49,50 | 18% to 30%30 Among patients with chronic allergic rhinitis, 30% experience worsening symptoms in pregnancy31 |

Elevate head of bed Reduce allergen exposure Nasal strips |

Hypertonic saline nasal rinse: safe to use31 Intranasal antihistamines (e.g., azelastine): acceptable to use Intranasal corticosteroids (e.g., budesonide, fluticasone [Flonase], mometasone): acceptable to use; helpful in chronic or allergic rhinitis; no proven efficacy for pregnancy-induced or nonallergic rhinitis49,50; budesonide, 50 mcg in each nostril once or twice per day, is the preferred agent and most widely studied in pregnancy Second-generation H1 antihistamines (e.g., cetirizine [Zyrtec], loratadine, fexofenadine): acceptable to use; cetirizine and loratadine are preferred Stimulant decongestants: avoid use; possible risk of congenital malformations51,52 |

OTC decongestants including pseudoephedrine, phenylephrine, and intranasal oxymetazoline are commonly used in pregnant patients.51 Multiple cohort and case-control studies show an increased risk of cardiac, limb, gastrointestinal, and ear birth defects with first-trimester sympathomimetic decongestant exposure.30,51,52 Until further research is available, physicians should advise patients that OTC stimulant decongestants may not be safe when used in early pregnancy.51 Dextromethorphan is generally considered safe in pregnancy based on historical use without observed increases in major malformations or other harms to the fetus.13 One case-control study (n = 184) did not reveal an increased risk of major malformations with first-trimester exposure.53 Human data on guaifenesin risks in pregnancy are weak and are possibly associated with neural tube defects and hernias in the newborn.54

Analgesics

Headaches are common during pregnancy. First-line OTC treatment options for headaches in pregnancy include acetaminophen and acetaminophen with caffeine.32 Total caffeine intake from medications, food, and beverages should not exceed 200 mg daily.32 Typical acetaminophen/caffeine tablets have 65 mg of caffeine.40 Data from a five-year retrospective cohort study support the use of prophylactic magnesium oxide, 400 to 800 mg daily, to reduce migraine frequency, severity, and duration during pregnancy.41 Physicians can consider nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) for the treatment of intractable migraines in the second trimester only.32

For low back pain, which affects up to 68% of pregnant patients,48 a Cochrane review reported weak evidence for the benefit of exercise and osteopathic manipulative therapies.55 If medication is needed, acetaminophen is first line.56 Transdermal lidocaine may be an option because there has been no demonstrated risk of malformations in human observation and lidocaine is not teratogenic in animal studies.13 Due to lack of human studies, lidocaine patches or creams should be applied only when safer options have proven inadequate.

As with other medications during pregnancy, acetaminophen should not be used indiscriminately. The total daily dose of acetaminophen should not exceed 4,000 mg. Maternal acetaminophen use is associated with an increased risk of asthma in the exposed infant (odds ratio [OR] = 1.34; 95% CI, 1.22 to 1.48; P < .001).33 In addition, recent concerns have emerged for prenatal acetaminophen exposure contributing to the risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, and other neurodevelopmental disorders in offspring.34–38 In 2021, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) released a statement asserting that studies have not demonstrated a clear association between prudent use of acetaminophen and adverse developmental outcomes.39 Acetaminophen should be taken as needed, in moderation, and after consultation with a clinician.39

Restricting use of OTC NSAIDs for analgesia to the second trimester is prudent. A National Birth Defects Prevention Study involving 29,078 cases over 14 years revealed an increased risk of 10 major congenital anomalies including hypoplastic left heart, tetralogy of Fallot, gastroschisis, and spina bifida.42 NSAID use after 20 weeks’ gestation may increase the risk of fetal kidney injury and subsequent development of oligohydramnios.43 Use after 30 weeks’ gestation can cause premature ductus arteriosus closure.43,44 Although topical NSAIDs have minimal absorption compared with oral NSAIDs, they demonstrate similar complications as their oral counterparts in case reports and should be avoided late in pregnancy.28,29

In contrast to other NSAIDs, low-dose aspirin is recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force and ACOG for women who are at increased risk of preeclampsia. Aspirin, 81 mg per day, should be initiated between 12 and 28 weeks’ gestation and continued until delivery (Figure 1).57–59 Consistent evidence from RCTs shows a significant risk reduction in peri-natal mortality, preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, and the risk of preeclampsia without an increased risk of bleeding.59 A small RCT demonstrated that low-dose aspirin does not increase the risk of ductus arteriosus constriction.60

Antipyretics

Fever during pregnancy is associated with cleft lip and palate (OR = 1.91; 95% CI, 1.3 to 2.8; P < .001)61 and neurodevelopmental disorders (OR = 1.24; 95% CI, 1.12 to 1.38), including autism spectrum disorder (OR = 1.15; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.31), particularly when it occurs in the first trimester.62 A 2018 systematic review (n = 10,304) did not show a reduction in the risk of neurodevelopmental disorders with antipyretic therapy, but it did support a trend toward higher risks of neurodevelopmental disorders if fever duration exceeded three days.62 Considering the dangers of the use of NSAIDs in pregnancy, acetaminophen remains the preferred treatment for fever.

Sleep Aids

Sleep deprivation may increase adverse pregnancy outcomes, including hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, gestational diabetes mellitus, maternal depression, placental insufficiency, medically indicated preterm birth, stillbirth, and low birth weight.45,63 Beyond addressing the contributing conditions and encouraging basic sleep hygiene, first-generation H1 antihistamines are acceptable for as-needed use and show benefit over placebo in reducing depression associated with insomnia in pregnancy.4,46 Melatonin easily crosses the placenta, and there are insufficient human trials to support its safe use in pregnant patients with sleep disturbance.45,47

Herbal Supplements

Approximately 29% of women worldwide reported taking herbal supplements during pregnancy.6 A 2019 systematic review of 74 articles involving 1,067,071 pregnant women examined herbal supplement use in pregnancy and the postnatal period. The conclusion of this review was to await more robust safety data before recommending herbal medicinal products during pregnancy.8 Table 3 summarizes the known safety and effectiveness data on commonly used herbs to aid in discussion with patients who may inquire about their use.6–9,64–66

| Herbal supplement | Use | Effectiveness | Safety concerns | Adverse reactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aloe (topical) | Acne, melasma | Possibly effective | Unsafe orally; insufficient evidence topically | Burning, erythema, itching |

| Chamomile | Rhinitis, dermatitis, multiple uses | Lack of evidence of effectiveness | Ductus arteriosus closure, increased preterm birth, low birth weight | — |

| Cranberry supplements | Prevention of urinary tract infections | Possibly effective | Second- and third-trimester spotting: avoid use | GI symptoms |

| Echinacea | Cold symptoms | Possibly effective | No safety concerns identified | GI symptoms |

| Garlic | Preeclampsia prevention | Lack of evidence of effectiveness | Insufficient evidence: avoid use | Abdominal pain, body odor |

| Ginger | Nausea and vomiting | Effective for reducing nausea | Late pregnancy use: bleeding/spotting, prematurity, reduced head circumference | Worsening nausea, gastroesophageal reflux disease |

| Peppermint | Nausea, irritable bowel syndrome | Likely effective for irritable bowel syndrome | Lack of evidence: avoid use | Abdominal pain, bloating |

| Raspberry | Labor induction | Lack of evidence of effectiveness | Increased cesarean delivery rate when used to induce labor: likely unsafe | GI symptoms |

| Valerian | Anxiety and insomnia | Insomnia: possibly effective Anxiety: lack of evidence | Insufficient information: avoid use | Drowsiness, GI symptoms |

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Servey and Chang67 and Black and Hill.68

Data Sources: An English-language electronic literature search was performed in PubMed, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database, and Essential Evidence Plus. The search was filtered for randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and evidence-based practice guidelines. Preference was given to studies published after 2014 to capture updated data since the last review article on this topic. Key words used included: pregnancy; pregnant concurrent with the following: nausea, vomiting, gastroesophageal reflux, constipation, hemorrhoids, acne, atopic dermatitis, eczema, tinea, upper respiratory illness, common cold, rhinitis, fever, headache, back pain, acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, aspirin, preeclampsia, herbal medicine, vitamins, minerals, and specific generic drug names or drug classes. We also used Micromedex, primarily to inform us on human data available for the medications mentioned within the article. Search dates: October 1, 2022, and July 13, 2023.