Am Fam Physician. 2025;112(4):359-361

Watch the video: AFP's 75th Anniversary Series: Interviewing Family Medicine Experts: Dr. Elizabeth Salisbury-Afshar

Read More About AFP’s Past, Present, and Future: This article is part of a yearlong series written by the editors of AFP to commemorate the journal’s 75th anniversary.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

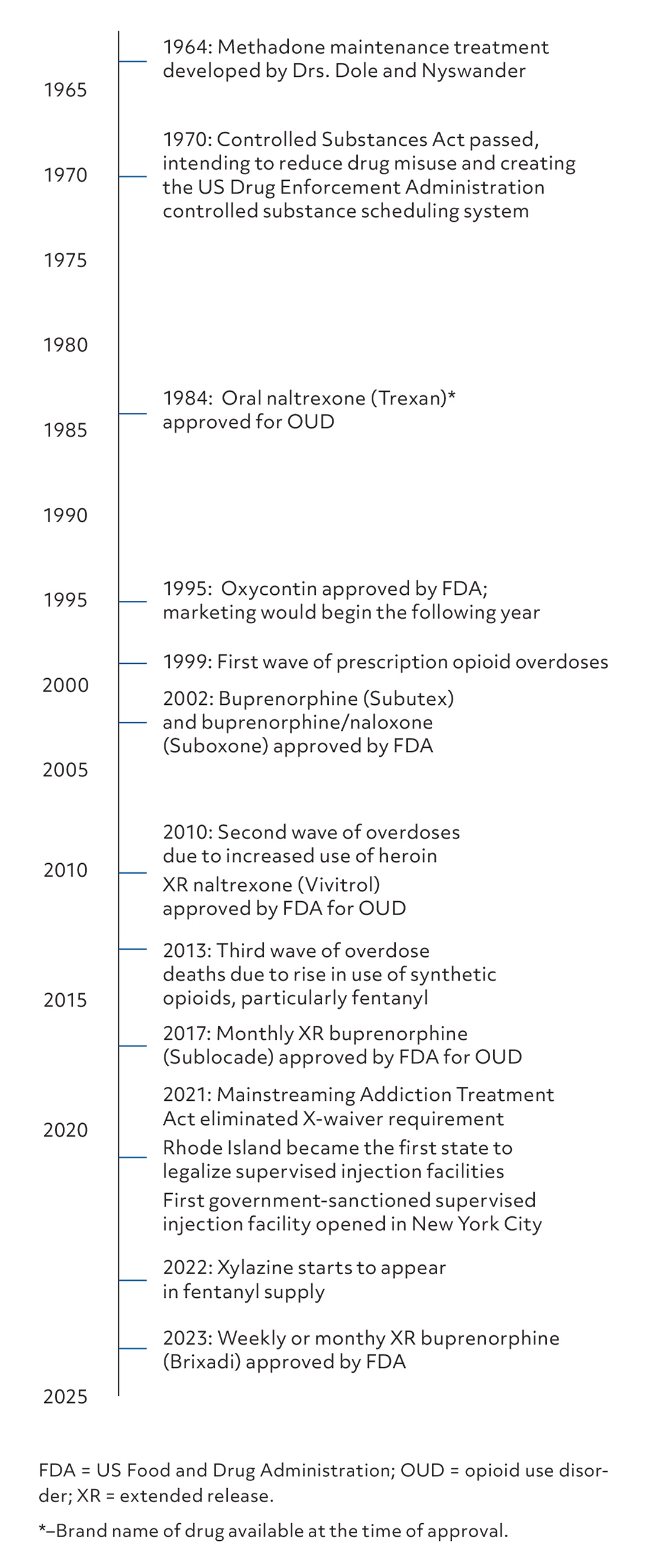

Over the past 75 years, changes in the epidemiology, understanding, and treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD) have been reflected in the pages of American Family Physician ( AFP). Articles have mirrored trends in the United States, presenting OUD as a relatively rare but devastating condition in the 1950s–60s, then covering the rise of heroin use in the 1970s–80s, the misuse of prescription opioids at the end of the 1990s, and the fentanyl epidemic of today. OUD is much more prevalent now than in the 1950s; fortunately, the variety and effectiveness of therapies have expanded significantly. Figure 1 illustrates milestones in OUD treatment over the past 75 years.1–10

Some debates around opioids are cyclical, whereas others show a clear evolution. In each decade of the past 75 years, arguments have occurred over how to balance the therapeutic benefits of opioids against concerns for dependence and diversion. Another area of ongoing debate is how family physicians should approach patients who are reluctant to stop using opioids. Perhaps the most significant shift over the past 75 years is the evolution from paternalism to partnership in the relationship between family physicians and patients with OUD. Addiction in the 1950s was seen as a moral failing; however, now it is considered by many to be a chronic disease. The definition of treatment success, too, has evolved from physician-mandated abstinence to patient-led progress to recovery.

A 1951 article was blunt: “The cause of drug addiction is not drugs, but human weakness,” adding that addiction is “a symptom of a personality maladjustment, rather than a disease in its own right.”11 The primary form of OUD during the 1950s was injected morphine, and the standard of care for treatment was a prolonged inpatient stay during which patients were transitioned to methadone and then slowly tapered off before discharge. The article cited a 15% rate of sustained abstinence after discharge.11 A 1960 AFP article echoed the stance that addiction is a personality disorder that leads to criminality and argued that abstinence, primarily through time in the penal system, was the only cure.12 However, a 1959 article stated that addiction should be seen as a medical, rather than criminal, problem and advocated for outpatient methadone clinics to help support recovery after hospitalization; the first such clinics would not be opened until almost a decade later.13

In the 1970s–80s, the focus of OUD articles in AFP was primarily recognition and management of the complications of OUD, such as cellulitis, septic pulmonary emboli, hepatitis C, infectious endocarditis, and osteomyelitis.14 Treatment of OUD was managed in specialized methadone outpatient clinics and was considered outside the scope of practice for family physicians. AFP articles discussed peer support groups, such as Narcotics Anonymous, as a valuable part of a therapeutic intervention.15 A 1972 article endorsed patient autonomy: “If he or she [the patient] decides against use of one or several chemicals, the decision will be the individuals' own and not imposed.”15 Although the 1980s saw the introduction of other medications for the treatment of addiction (eg, naltrexone), treatment of OUD was still not considered within the purview of family physicians.

The 1990s saw the introduction of the concept of “pain as the fifth vital sign” and the subsequent rise in opioid overprescription and misuse16; AFP covered both trends. Most articles took a consistently skeptical approach to the use of opioids for pain management, and one article reviewed responsible prescribing of controlled substances, including how to look for signs that a colleague may be overprescribing.17,18 The journal also published articles that promoted a nonjudgmental approach to treatment of patients with substance use disorders.19,20 However, judgmental language was still notable during this decade with warnings stating, “Addicts are often extremely manipulative and tend to lie, falsify their symptoms and use several physicians to obtain prescriptions. These patients may be hostile and demanding.”17 Articles also used especially critical language to describe physicians who overprescribed controlled substances, stating that they were “dated, duped, disabled, or dishonest.”20 Not only were patients with OUD being judged, but so were well-intentioned clinicians treating pain.

Throughout the 2000s-10s, AFP consistently questioned the benefits of opioids for noncancer pain, while increasingly promoting the role of family physicians in office-based treatment of OUD.21 A 2012 editorial reviewed the American Academy of Family Physician's stance on pain management and OUD and accompanied a review article on use of opioids for chronic nonterminal pain.22,23 Additionally, several articles reviewed details about how to treat OUD in the clinic setting and provide primary care to people who inject drugs.24–29

We're only halfway through the 2020s, but several articles on OUD management and harm reduction have already been published, emphasizing the expanding role that family physicians play in OUD management.30–33 Harm-reduction strategies are now openly recommended, and previously taboo policy proposals (eg, supervised injection sites) have been discussed in AFP editorials.31,34 There is a hint of hope for the future, with one article acknowledging that “the United States is slowly making progress in reducing opioid prescribing in response to the opioid epidemic.”35

Over the past 75 years, AFP has shifted from framing opioid addiction as a moral failure treated only in specialized settings to recognizing OUD as a chronic disease that family physicians can partner with patients to manage through office-based care and harm-reduction strategies. This evolution highlights the movement toward treatment models that are patient-centered and collaborative.

What AFP Means to Me as a Patient Advocate

I accepted the role of writing “patient perspectives” for AFP several years ago. I have eagerly cowritten a score of these, believing that the physicians reading the journal would gain further insight into how patients feel about their illnesses and medical care. What do patients worry about and fear while engaging in shared decision-making with their family physician? They want to know a truthful prognosis even if it is bad news. They want to know how their care will impact their lifestyle. They want to know all their options. The opportunity to catch the eye of hundreds of thousands of physician readers is unique and lends purpose to my efforts to advocate for patients. As far as I know, this opportunity is unique among medical journals.

John James, PhD

Editor’s Note: The authors are editors of AFP.