Two key characteristics will help you to ensure that your notes communicate not only what you did, but also what you were thinking.

Fam Pract Manag. 2011;18(4):15-17

Dr. Crownover is the program director of the Nellis Family Medicine Residency, Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada, and an assistant professor with the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Md. This article represents the views of the author and does not represent the views of the U.S. Air Force, the Defense Department or the U.S. Government. Author disclosure: no relevant financial affiliations disclosed.

How many times have you read a medical note that does not make the selection of the diagnosis or treatment clear? Have you ever read your own notes after receiving notice of a malpractice suit and winced at the inconsistencies?

Poorly constructed medical notes are a widespread problem. I've seen it while reviewing the charts of medical students and residents to ensure that they met the standard of care and avoided malpractice risk. While most physicians document history and physical data with the required number of CPT elements, few clearly convey a line of reasoning that reveals their clinical thought process. A note that documents a detailed history and moderately complex decision making does not necessarily illuminate why certain decisions were reached or why a particular treatment was justified.

I wanted to find out where in the educational process students learned key documentation concepts, so I did some research that included informally querying medical students from multiple medical schools who were rotating at our residency. None of them could describe learning a formal structure for completing assessments and plans, which is consistent with a study that found only 4 percent of standardized encounters were accurately charted by medical students.1 I also discovered that the 2010 United States Medical Licensing Examination clinical skills exam guide states that students are expected to present a list of differential diagnoses in order of likelihood along with desired evaluations, but no requirements existed for discussing the clinical rationale.2

As a result of these and other findings, I developed a formal framework, described in this article, to teach residents and students an appropriate way to construct their notes. The initial feedback has been highly positive.

Documenting a confirmed diagnosis

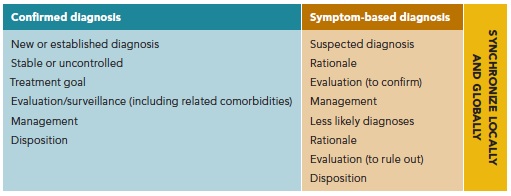

To begin, let's review what should be included when documenting a confirmed diagnosis. Generally, six elements are needed (see also “The structured note” summary).

New or established diagnosis. The first element overtly communicates to coders whether the diagnosis is new or established, since this helps to determine code selection.

Controlled or uncontrolled. The second element should communicate whether the status is controlled or uncontrolled, which also directly affects complexity and reimbursement.

Treatment goal. The treatment goal should be clearly stated. How can one justify the decision to refill, increase or decrease a medication if the desired benefit is undefined? For example, simply refilling albuterol for asthma may actually hurt the patient if he or she needed a controller medication after reporting daily rescue medicine use.

Evaluation or surveillance. Any evaluations or testing, whether for the intrinsic disorder or for comorbidities, must be included in the plan as the fourth element. For instance, ordering an A1C test is beneficial in monitoring diabetes, but the evaluation element also reminds physicians to screen for diabetic reti-nopathy or hyperlipidemia.

Management. Documentation of treatment or management should always be listed, even if only to write, “Continue carvedilol 12.5 mg bid.” Using action verbs such as “resume” or “increase” helps communicate the treatment instructions.

Disposition. The final element is disposition. This is likely to include instructions for the patient to return to the clinic after a certain period of time, criteria that should prompt him or her to call the office sooner than scheduled and any actions the patient should perform at home, such as keeping a food diary or blood pressure log.

Following this structure, a note for a confirmed diagnosis might look like this:

Hypertension: Established, uncontrolled by home blood pressure (BP) log; systolic BP in 150s. Treatment goal: systolic BP in 130s. Complete chemistry pane/ipid/rinalysis in one week. Increase lisinopril now to 20 mg every morning, 60 tabs, five refills. Consult nurse education for dietary approaches to stop hypertension (DASH diet). Return to clinic in one month with BP log.

Asthma: Established, controlled. Treatment goal: albuterol needed less than three times weekly. Complete annual pulmonary function tests at next visit. Refill mometasone 220 mcg one puff daily. Continue albuterol two puffs four times daily as needed. Return to clinic in three months or sooner per asthma action plan.

Documenting an unconfirmed diagnosis

When documenting an unconfirmed or symptom-based diagnosis, two elements borrowed from the five-step “microskills” model can enhance the note and provide a glimpse into the physician's thoughts.3 It is critically important for the physician to commit to a diagnosis and explain why, among the various differential options, this suspected diagnosis is most applicable to this particular patient. Testing to confirm or rule in the working diagnosis should be listed along with empiric or symptomatic treatment. Less likely diagnoses should be listed next, along with why they are not as probable and how to rule them out. Finally, parameters for reviewing the evaluation and treatment response should be defined. See also “The structured note.”

Following this structure, a note describing symptom-based diagnoses might read as follows:

Abdominal pain: Suspect biliary dyskinesia due to epigastric location, relation to fatty meals, body habitus and negative right-upper-quadrant ultrasound for gallstones. Confirm with cholescintigraphy (HIDA). Treatment: fatty food avoidance. Doubt pancreatitis given nondrinker and negative ultrasound, but rule out with amylase/lipase. Doubt gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) given proton-pump inhibitor use and contrast to usual GERD symptoms. Return to clinic after HIDA scan and consider surgery consult.

Rash: Suspect allergic photodermatitis given location in sun-exposed areas and onset after use of new sunscreen lotion. Confirm by stopping lotion. Treatment: PABA-free sunscreen. Doubt lupus given no prior history and absence of other complaints. Doubt prescription medications due to no admitted use. Return to clinic if symptoms persist after lotion change.

The structured note

The table below shows the essential components of a detailed assessment and plan.

Synchronicity

Finally, synchronicity should be evident in every note both globally and locally, that is, both within and across the major sections. For example, the past medical history should match the medication list. If it doesn't, a reviewing physician may wonder what other aspects of care were sloppy or incomplete. Here's an abbreviated example of poor local synchronization:

Past medical history: hyperlipidemia, COPD.

Meds: tiotropium, lisinopril, levothyroxine.

Synchronicity between the subjective/objective (S/O) and the assessment/plan (A/P) sections of the note is also important. For example, if the physician documents three abnormal items in the S/O section, but the A/P only lists two diagnoses, then a mismatch exists between abnormal data collected and assessments made. Not only might this pattern result in underpayment, but it also puts physicians in indefensible positions if a malpractice case ensues. Most important, it may contribute to patient harm.

Here's an abbreviated example of poor global synchronization:

Subjective/objective abnormal data: Epigastric burning pain at bedtime, non-scarring hair loss three months postpartum, loss of urine with coughing and laughing.

Assessment: GERD, telogen effluvium.

Summing it up

Structure and synchronicity are part of disciplined note construction, which is critical to effective communication between physicians. Better documentation may also contribute to clearer medical decision making, which is needed for reimbursement and malpractice defense. Instruction in comprehensive note writing should be promoted in early predoctoral education and continued throughout postgraduate medical training.