Being an employed physician and being well shouldn’t be mutually exclusive. Here’s how to succeed at both.

Fam Pract Manag. 2022;29(5):29-34

Author disclosures: no relevant financial relationships.

The changes that have occurred in health care over the past 30 years have been dizzying. From the movement toward managed care in the 1990s to the publication of the joint principles of the patient-centered medical home in 2007 to the Affordable Care Act in 2010, the Cures Act in 2016, and the Cares Act in 2020, the evolution of the provision of health care in general — and primary care specifically — has been unprecedented. These changes are only accelerating with ongoing corporate consolidation, economic pressure, COVID-19 impact, and advances in biotechnology, wearable technologies, and use of artificial intelligence in health care.

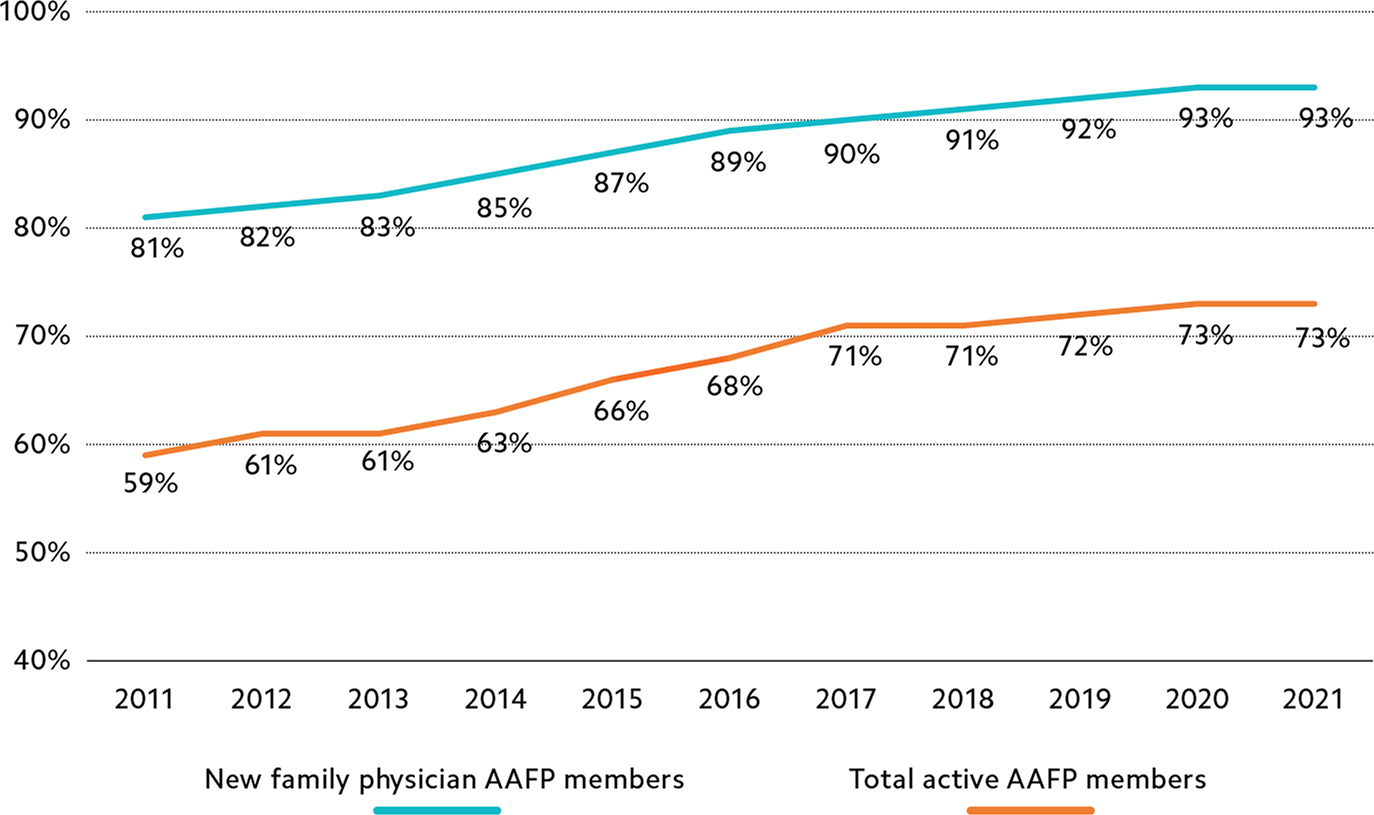

In the midst of all this, the answer to the question “Are you employed?” has gone from a coinflip in the early 2000s to 73% of family physicians being considered employed in 2021, including 93% of new residency graduates.1 This means the vast majority of us are now contracted by a larger organization, such as a single-specialty or primary care group, a larger multispecialty group or health system, or a health insurer. Recent surveys indicate this trend is not unique to our specialty.2,3

Our intention with this article is not to speculate whether these changes are “good” for family medicine, individual physicians, or our patients. Rather, this article addresses skills that most of us never learned during our training: how to be employed “well.”

KEY POINTS:

Today, 73% of family physicians are considered employed, but many were not taught during training how to be employed “well.”

By choosing employment, you become part of a much larger system and play an important role in helping the organization achieve its goals.

Although “being organizational” is important to your career success, you must also pay attention to your own needs, or you will be at risk of burning out.

HOW WE GOT HERE AND A WAY FORWARD

In the early days of the movement toward employment in the 1990s and early 2000s, the foundational impetus for physicians was to gain negotiating leverage with insurance plans.4 While this is still relevant, recent motivations for employed practice include having more regular work hours, a predictable salary, less up-front financial risk, call coverage, a benefits package, the opportunity to pay off loans, an electronic health record (EHR), improved support for quality initiatives and care coordination, a potential subspecialty network, and someone to manage staffing. Additionally, employed practice often provides additional staffing and resources to assist with prior authorizations of medications and procedures, referrals, medication assistance paperwork, and form completion. With each benefit of employment come trade-offs in terms of autonomy, control, flexibility, and influence. If a physician’s idea of being employed is simply to be provided a salary (or compensation model), building, manager, and staff and then be left alone to practice autonomously, they will likely not find themselves employed “well.”

Because of these trade-offs, some physicians believe they must compromise their personal or professional principles in the process of becoming employed. However, we believe there are practical ways to maximize the upsides of employment while minimizing the concerns. We have divided these strategies into two categories: “being organizational” and “being well.”

BEING ORGANIZATIONAL: OPTIMIZING YOUR RELATIONSHIP WITH YOUR EMPLOYER

By choosing employment, you become part of a much larger system and play an important role in helping the organization achieve its goals. As such, it is vital that your interests be aligned with those of the organization. This does not mean you must agree with everything the organization does, but shared interests will make the relationship more effective and rewarding. Providing exceptional patient care while maintaining financial viability is often the underlying stated goal; however, understanding what this means through the lens of the organization will help you assess and achieve alignment. Here’s where to start:

Understand the organization’s mission, values, and priorities and how your work advances them. For most organizations, the mission includes caring not only for individual patients but also for specific populations and the community as a whole. While your day-to-day focus will be on your patient panel, understanding how your work fits in with the larger mission is essential. Additionally, organizational priorities may not be focused exclusively on your work in primary care, which can feel frustrating, but this too can help you see how your work connects with the whole. At times, there will be tension between the organization’s values and your own, and you will have to decide whether to speak up or withhold your personal opinions. Focusing on the larger goal can help you choose your battles and be more effective.

Get to know your leadership. Learning how to effectively interact with your clinical and administrative leadership is vital to ensuring you are informed and aligned with organizational priorities. This will ultimately put you in the best position to advocate for yourself and the patients you care for.5 This includes learning what is important to leadership and how their success is measured. When you sense mis-alignment, discuss it professionally and respectfully. If at any point you reach an impasse, understand how to navigate the organizational leadership structure to appropriately involve others.

Be a good organizational citizen. Understand that you are a teammate on a large team and become involved with your practice, department, or organization through work on committees, task forces, and initiatives that could benefit from your skills and fit your interests. Share what you are learning with your colleagues. Get to know your practice, department, and sub-specialty colleagues and understand how best to interface with them. If your organization participates in undergraduate or graduate medical education, consider getting involved as a clinical educator and understand what is expected of you in this capacity. Additionally, be intentional about developing your professional reputation and treat colleagues, staff, and administrators with respect. Understand the most effective process for giving feedback and providing suggestions, and then do it. For example, when you need to give feedback to a staff member or colleague, it’s usually best to do so privately, rather than going straight to their manager, and focus on the process not the person. Follow organizational rules, policies, and expectations, and complete your administrative work, particularly chart completion. If you are having difficulty doing so, ask for help and seek out best practices.6 Don’t develop a reputation as someone who always needs to be reminded about these things. Every time your name shows up on a “list,” it chips away at your organizational reputation.

Understand how your work is valued and brings value to the organization. Most organizations still use physician compensation models that emphasize productivity and offer physicians a base salary plus a performance bonus based on work relative value units (RVUs) or some other measure of productivity.7,8 However, value-based performance bonuses are becoming more common. They are based on factors such as quality metrics, referral patterns, cost containment, downstream revenue, value-based care and shared savings, professional reputation, and community engagement. Knowing what your employer values can help you focus your efforts on what will be most effective for both you and your organization.

Be about quality, safety, and outcomes. Take responsibility for your performance, including quality metrics, clinical outcomes, technological aptitude, and cost/value. If you see an opportunity for improvement, understand the process for addressing the issue and work through that structure. When doing so, seek first to understand multiple perspectives. Don’t assume your way is necessarily better, but do speak up and share your ideas for improvement.

BEING WELL: LEVERAGING YOUR EMPLOYMENT STATUS TO ENHANCE YOUR PROFESSIONAL AND PERSONAL WELL-BEING

Although “being organizational” is important to your career success, you must also pay attention to your own needs, or you will be at risk of burning out. Some physicians have found that employment has not provided the benefits they had hoped for.9 Following a few simple guidelines can help ensure that you are benefiting from your employment status.

Start well and help others do the same. Take full advantage of your employer’s onboarding process.10 This is the time to ask questions and make sure you understand the structure of your individual practice, clinical departmental, and organization, including leadership roles and available resources. Make the most of initial opportunities for training around the EHR as well as follow-up opportunities. Be sure this occurs for any new partners to your practice as well. If you’ve not already done so, consider seeking out a mentor to help guide your career development.

Take an active approach to your practice. Being employed can be interpreted as only needing to focus on patient care and meet minimum expectations in the “nonclinical” aspects of the practice, but doing so is not in your best interest. By virtue of your medical degree and training, others in your practice will be looking to you for leadership. Helping to build an intentional practice culture, efficient work-flows, and an effective team will provide greater satisfaction in your work while aligning with the work of your leadership.11 Get to know the members of your practice — leadership, colleagues, and staff — and ensure your group is having regular practice meetings and even social gatherings to optimize communication and collaboration. While the organization can help market and build your practice, it is important to engage with your community to help shape and grow a practice that brings you fulfillment. Additionally, be an advocate for your practice and your team with leadership. Your ideas are likely to help others in the organization as well.

Understand how to optimize your income potential. You must read your contract and know how you will be paid. We find this is frequently a point of frustration for colleagues, particularly if they are transitioning from a guaranteed salary to a performance-based model. (See the AAFP’s employment contracting resources.) Though most contracts emphasize work RVU productivity, the majority also include incentives for such things as quality, panel size, supervision, and student education. Pay attention to this data, and make sure you know how you can improve your numbers, not just for the benefit of your compensation but also for your patients. While it is tempting to want to maximize your income, balancing that desire with other parts of your life is essential. Understanding appropriate documentation in order to optimize billing and coding is also vital. (See FPM’s coding topic collection.)

Be about improvement. Actively monitor your individual quality metrics with a plan to address any lagging metrics with both your care team and your partners using a PDSA (plan-do-study-act) process. Seek an understanding of the rationale for and pertinent guidelines regarding the choice of quality metrics. Learn best clinical practices from colleagues and leadership. Huddle daily with your team to ensure alignment of mission. Understand the distinction between “professional principles” vs. “style preferences” and seek clarification before you dig in on an opinion about anything practice related. For example, completing charting in a timely manner (e.g., within 24 hours) is a good professional principle to follow, whereas completing charting during the patient visit is a style preference. Take advantage of process development and quality improvement opportunities and resources. (See the Institute for Healthcare Improvement’s resources.) Finally, understand the peer-review process that exists within the organization and how it operates.

Gain back some autonomy and influence. Standardization has its place within an organization, but it’s also important to give physicians some freedom and control over their work as long as they can deliver the desired outcomes. If there is an area where you desire more autonomy, such as your schedule, don’t ignore the issue or just complain about it. Make the case for what you need. You do have some influence by virtue of being a physician. By building a good reputation within the organization and getting to know your leadership, as outlined earlier, you will be able to expand your influence and advocate for yourself. This will sometimes entail providing uncomfortable feedback and suggestions to your site leadership, in meetings, and in performance reviews, but learn to do it tactfully, in part by building your emotional intelligence.12 Be part of the solution by offering to pilot a change or by joining a committee to address important issues (such as quality, well-being, EHR enhancement, compensation, peer-review, or value-based care).

Leverage organizational benefits and resources. Take advantage of opportunities provided by your organization for your support, improvement, and development. This can include CME opportunities, EHR training, practice support, leadership development, faculty development, employee assistance programs and other emotional health resources, peer support, legal support, and general well-being resources. Be sure to take all your vacation and CME time, and ensure you have the necessary coverage when you are gone. Look to become efficient with administrative tasks by doing what is necessary and important, but streamlining the processes as much as possible.

Stay united with your professional colleagues. Given that there are potential conflicts between the interests of health care organizations and the interests of physicians and their sense of professional duty, it is essential to stay involved with your state and national medical organizations. Their collective voice and advocacy efforts can help ensure that “checks and balances” are maintained and that physician and patient interests are protected in health care policy, payment, and other matters.

Attend to your own needs. Whether employed or independent, the work we do as physicians can be challenging and at times feels overwhelming. Schedule regular time for self-care (vacations, hobbies, exercise, social connections, or even catch-up time on your schedule), and encourage your teammates to do the same. Self-care is not selfish; it is sanity and good stewardship from both an individual and organizational perspective. The cost of replacing you is substantial, so set reasonable boundaries and discipline yourself around your work to ensure you protect this “investment” — you.

BEING WELL AND BEING EMPLOYED

None of us are immune from the challenges of practicing medicine in 2022 and into the future. Present trends and future projections indicate that the majority of family physicians will be employed by some type of organization through the remainder of our careers. While we may have to make tradeoffs when comparing practice ownership with employment, we do not have to make compromises in terms of quality patient care or professional satisfaction. What we have shared here are some of the lessons we have learned through our own experience serving many years as both clinicians and leaders in a large integrated physician group and health care system and through many of the changes described in the introduction. We hope this will provide you some additional ideas as to how you too can be well while being employed.