Understanding the various payment models can help physicians navigate potential pitfalls and make sure incentives are aligned.

Fam Pract Manag. 2022;29(5):23-28

Author disclosure: no relevant financial relationships.

The landscape of physician contracting is becoming as complex as health care in general. The challenges to constructing reasonable compensation models (“comp models”) for physicians in group practice or within health systems have increased as the number of different payment models from insurers has increased. More restrictions from the Stark statute have also affected how comp models are constructed. This article will look at some of these issues, including five models of physician payment, the often-backward incentives in these models, potential contract pitfalls, and Stark law compensation restrictions that apply within physician groups.

Although individual physicians may not be able to negotiate significant changes in payment with insurers or their employers, they should be aware of potential pitfalls and incentives. All physicians need to understand how the group is being paid and how their personal performance affects payment. Practices should also take into account how payers are paying them when they design their internal compensation models so that all incentives in the practice are aligned.

KEY POINTS

All physicians need to understand how their group is being paid and how their personal performance affects payment so that incentives can be aligned.

Each physician payment model comes with advantages as well as pitfalls and sometimes backward incentives.

Restrictions from the Stark statute also affect how physician compensation models are constructed within a group; the two permitted compensation mechanisms are personal productivity and profit sharing.

FIVE PAYMENT MODELS

Five physician payment models are most prevalent today.1

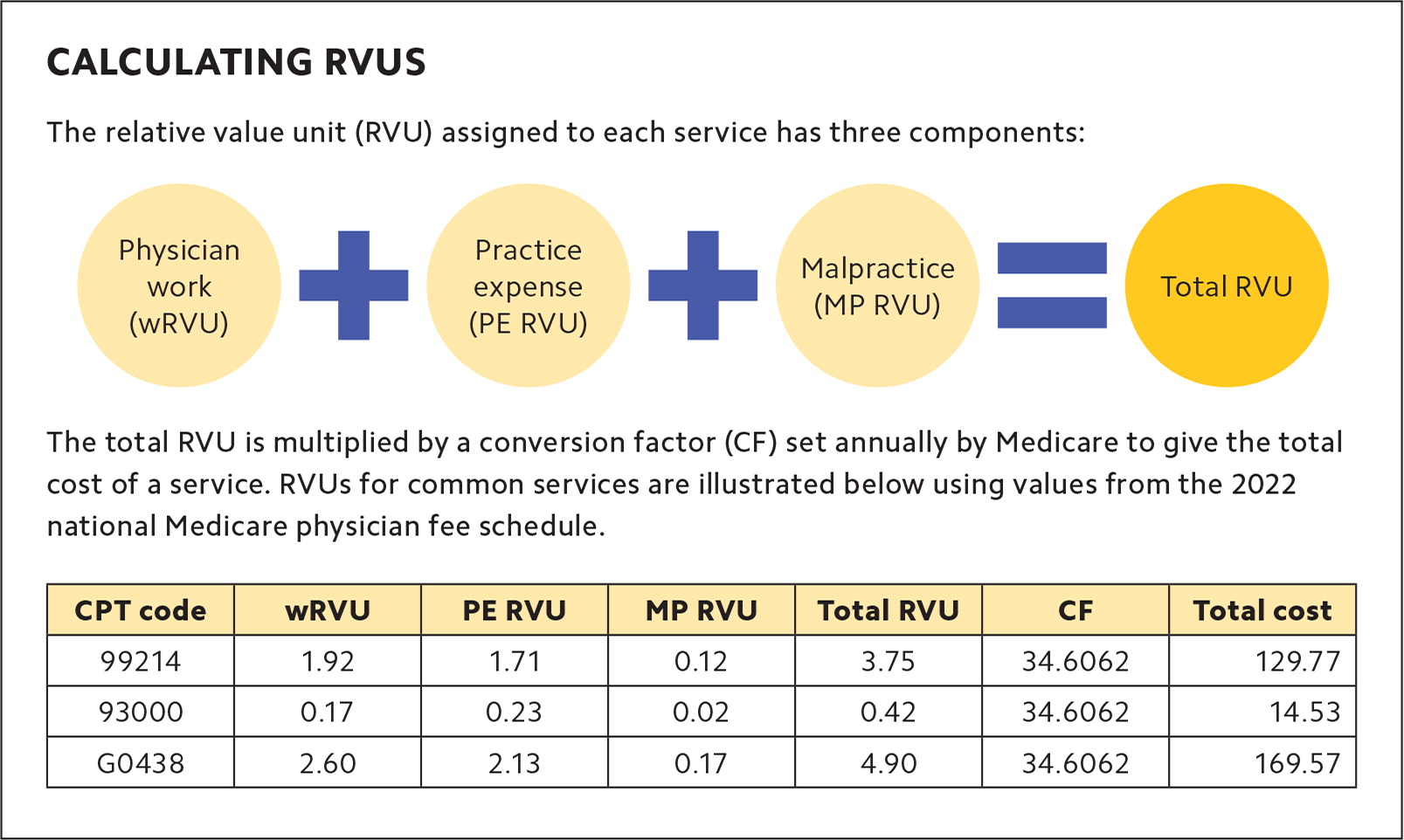

1. Fee for service (FFS). This model rewards productivity and provides a separate payment for each service performed. The value of each service is based on the Resource-Based Relative Value Scale (RBRVS) and is made up of three components: physician work, practice expense, and malpractice. The physician work RVU component is the one most physician comp models use. (See “Calculating RVUs.”)

The advantage of FFS is that it captures work done in the office in a tangible, measurable, billable way. Unfortunately, this also incentivizes providing more services: “do more, get paid more.” This can lead to a competing set of interests between holding down overall cost while maximizing income.

The contractual pitfalls begin with whether the contract specifies where the data will come from to determine the proper physician payment — the medical record, which is closest to the actual performance of the service, or a claim form, which may not represent what was done. For example, you might see a 55-year-old patient for a physical examination and also address their knee pain. You submit a bill to the insurance company for 99396 (physical examination, established patient, age 40 to 64) and 99213-25 (office visit, established patient, level 3, with modifier 25 to indicate a separate E/M service). An insurance company may refuse to pay for the 99213 and instead reimburse only the 99396. So while the medical record reflects 6.35 total RVUs performed, only 3.69 will get paid. To overcome this discrepancy, FFS-based comp models must have a mechanism for capturing the actual work done, independent of what a payer reimburses.

Historically, FFS models failed to reward physicians for non-face-to-face services because they often weren’t billable.2 But relatively new codes for services like transitional care management and chronic care management can help physicians more accurately capture what they actually do for their patients. Of course, there are obstacles to using these codes, including medical necessity requirements, specified time requirements, preconditions for the services (e.g., hospitalization prior to using the code), or personnel qualifications for rendering the services (e.g., for chronic care management).

Outpatient E/M coding changed in 2021,3 with the intent to reduce documentation burden. Physicians can now code outpatient/office E/M visits based on either the level of medical decision making or total time spent on the day of the visit. Still, there are some pitfalls. These include 1) whether the physician uses accurate coding and documentation, or accurate capture of time spent, as this will affect payment and 2) whether the agreement states explicitly that the payer adheres to Medicare’s current coding rules or applies some other idiosyncratic approach.

2. Capitation. Under this model, payments made to physicians are based on a per-member-per-month payment, typically made prospectively for the month. In other words, a primary care physician would receive $X per month to care for each patient on their panel, regardless of whether the patient’s actual costs are more or less than that amount. “Global” capitation refers to models where the monthly payment covers the vast majority of services patients will receive and practices must then pay other providers who deliver care to their patients. “Percent of premium” is very similar to capitation, but the amount is based on a portion of the premium paid by the patient.

The benefit of a capitated payment model is that because income is not tied to a traditional face-to-face office visit or billable service, it supports nontraditional encounters with patients. Therefore, this model can encourage innovative care models and keeping patients well. Unfortunately, this model can also incentivize undertreatment or treating only healthier patients to make that monthly payment go further.

The biggest contractual challenge is whether the agreement states explicitly what services are included within the capitation rate. Typically, in primary care, capitation includes not only the office visits themselves but also routine vision and hearing screening; preventive diagnostic and treatment services; in-office health education and counseling; injections, immunizations, and medications administered in office; and outpatient laboratory tests conducted in office. A second challenge is whether the physician can bill for services outside the capitation rate. Many payment models have a blending of capitation and FFS to help overcome these obstacles. Other issues that ought to be addressed explicitly in the payment contract are how patients are assigned to physician panels and what happens if two physicians claim the same patient for their panels. Capitation success depends on efficient panel management, so patient panels must be well defined.

The essential question here is whether the capitated payment amount is sufficient to cover the services to be provided. The physician must deliver care efficiently so as not to exceed the payment amount. One of several reasons the Allegheny health system went spectacularly bankrupt in 1998 was that it was paid 85% of the premium dollar, but its medical loss ratio (how much it cost to deliver services) was 95%, an unsustainable circumstance.

In global capitation or percent-of-premium payments, the essential challenge is what type of risk devolves onto the physician. Technical or medical risk is the risk of operating efficiently within the budget the payment rate provides; this is a fair risk for physicians if the payment rate is fair. Incidence risk, also called probability risk (an insurance term), is the likelihood that an illness will occur in the covered population. But if the local health plan sells its product to the local coal mine, the incidence of lung disease will likely outstrip what the actuaries took into account, so the payment rate may not adequately cover the acuity of the patients who are covered by it. Physicians cannot control for this and should not have to undertake such risk. While discussions and negotiations around these payment issues will likely take place at the board or C-suite level, all physicians need to understand how the group is being paid.

3. Pay for performance (P4P). This payment model provides an additional quantum of dollars for meeting some predetermined standard. Sometimes it is absolute — e.g., for each patient with diabetes whose A1C is below 7%, the physician gets paid $X. Sometimes it is relative — e.g., the top 1% of physicians are eligible for performance payments. P4P is often less subject to negotiation with insurers, and in its earliest days was not even documented in contracts. It was just an opportunity posted on a health plan’s website. It has faded some in popularity, in part because the incentives weren’t large enough to change behavior.

Many of these early P4P models have evolved over time to include a broader set of measures (including cost metrics) and a wider range of incentives in an effort to reward physicians for delivering value. While some value-based contracts simply offer a bonus at the end of the performance period, others may use a blend of the payment models discussed in this article, such as prospective or bundled payments.

A key challenge is defining the source of data to determine payment. If payment is for clinical performance (e.g., improving outcomes related to diabetes or providing smoking cessation), the medical record is the best source of data. If payment is for financial performance (e.g., lowering the number of emergency department visits while increasing office visits), claims data is a reasonable source. If the program is relative, it is important for the participating physicians to get reports on how they are doing during the performance time period. How to challenge the payment determination ought to be stated too.

4. Case rates or episode of illness rates. Surgeons have been paid based on case rates for years. They get one payment that covers anywhere from the same day to 90 days of services related to their surgery. Case rates in primary care are condition-specific (e.g., diabetes, congestive heart failure, or asthma) and cover a defined period of time (e.g., 90 days, six months, or a year). Contract terms here ought to address whether comorbidities that arise during the covered period break the case rate or continue in parallel. In other words, if a patient’s care is being paid on a case rate for congestive heart failure and he is in a car accident, does the case rate continue? What if he develops cancer? Case rates are sometimes applied by paying the providers in the ordinary course (e.g., based on FFS for physicians and based on diagnosis-related groups for hospitals) and then gainsharing any savings at the conclusion of the case.

Contract challenges include provisions for how to dispute the distribution of gain-sharing money and what to do if two physicians claim the same payment. Critical issues also include what triggers the rate (e.g., an ICD-10 or CPT code) and whether the episode reaches back in time to capture services that preceded the trigger, such as the diagnostic services that led to the diagnosis. At the other end of the process, when does the episode end (e.g., how many days post-discharge or post-procedure), and what breaks the case? If the rules are not specified in the contract, a method for resolving them (e.g., a joint operating committee) should be specified. Some case rates are also bundled payments.

5. Bundled payments. Bundled payments apply where two disparate providers not otherwise affiliated join in the delivery of care to a single patient.4 Most bundled payments are based on case rates. Before entering into these arrangements, several questions must be answered: Among the providers participating in the bundle, to whom is the payment made? How will that money then be allocated among the other participants? What happens to payment disputes among the participants?

Depending on the length of the bundle, participating providers will need reports of their progress toward the goals incentivized in the bundle. What reports and how often they will be made available should be specified in the contract. There are a host of issues that may become subject to dispute resolution (e.g., whether an episode was triggered or broken, and whether a provider qualified for an upside payment or should pay on downside risk, if any). These issues are beyond the scope of this discussion but need to be carefully confronted in the payment contract.

WHAT STARK SAYS THAT MATTERS

The Stark statute, also known as the physician self-referral law, prohibits physicians from making referrals to entities in which they have a financial interest. It applies only to Medicare and Medicaid services, and then only for referrals for designated health services (DHS). In-office services that are considered DHS include clinical laboratory, physical and occupational therapy, imaging, radiation therapy, outpatient prescription drugs, speech and language pathology services, parenteral and enteral nutrient equipment and supplies, prosthetics and orthotics, and durable medical equipment.

Because the Stark statute considers referrals among the physicians in their own group to be implicated, the statute and regulations address physician group internal compensation.5 To qualify as a group practice eligible for physician-to-physician referrals and physician-to-ancillary services referrals, the compensation within the group must comply with the Stark rules. The two permitted compensation mechanisms are paying a physician for personal productivity and profit sharing.

Personal productivity. The statute allows physicians to be paid for their personally performed services as well as for services “incident to” their personal services. “Personally performed services” means literally no one else is involved in the delivery of the care. For example, if the physician directly applies the diagnostic ultrasound wand to the patient with no technician involved, that physician can get credit for both the technical and professional components. If a technician does the diagnostic ultrasound, then those technical components may only be allocated in profit sharing (addressed below).

“Incident to” is a long-standing payment principle going back to the inception of Medicare. It is what permits a physician to be paid for the services of an advanced practice provider (APP), medical assistant, nurse, or other ancillary personnel. In incident-to billing, the service is deemed an integral although incidental part of the physician’s personal professional service to the patient, and it is billed as if the physician performed it. Generally, Medicare reimburses at 100% when a service is billed incident to a physician and 85% when those same services are billed under the name of the ancillary provider. The ancillary personnel are essentially invisible on the claim form with incident-to billing. To bill for a service incident to a physician, first there must be a physician service to which the incident-to service relates. This is why an initial visit with an APP, for example, cannot be billed incident to unless the physician is already treating that patient.

A major restriction for incident-to services is that a physician “in the group” (including a partner, employee, or independent contractor) must be on the premises, in the office suite, and immediately available throughout the time the incident-to service is rendered. The specialty of this supervising physician is irrelevant, and they need not have a treating relationship with the patient at all. As an example, a family physician in a multispecialty group could be listed as the supervising physician for cardiac monitoring performed by an APP. Even more bizarrely, who is listed as the supervising physician on the claim form is irrelevant to who can be given dollar-for-dollar credit in their compensation for the incident-to services. The physician who can get credit is the treating physician to whom the services are incidental. Then, there is the further conundrum that no diagnostic testing may be billed incident to a physician. No laboratory services, no electrocardiograms, and no electroencephalograms — none of them can be allocated incident to a physician’s services, whether they are DHS or not. Those dollars may be allocated as part of profit sharing.

Profit sharing. Profit sharing is how physicians may be compensated for the “fruits of others’ labor” — dividing the income derived from DHS among all providers in a group. Diagnostic testing technical components (and professional components not provided by the compensated physician) may be allocated this way. For Stark-defined DHS (listed previously), only physicians “in the group” may be paid profit sharing; this includes partners, employees, and independent contractors (only when those contractors are on the premises of the group).

Before 2022, many groups allocated profits by modality. They had physicians who participated in the imaging pool, the infusion pool, and the physical therapy pool, for example. The “pool” is that cumulation of profits generated by the specific modalities. In a change as of Jan. 1, 2022, this is no longer allowed. To share profits from DHS, they must be in a single pool. That said, it is permissible to allocate those profits to subgroups of at least five physician in different ways. For example, a large group might have six physicians who share a portion of the single pool based on their E/M visits. Another subgroup might share their profits based on seniority. There are a range of potential approaches, including allocating by historical practice patterns, which might include past patterns of referrals for DHS. All physicians in a group should understand how they are being paid profits, if at all.

THE BOTTOM LINE

The context for creating physician compensation models has become significantly more complicated. This article only touches on the principal challenges physician groups confront in creating equitable, compliant compensation. Now more than ever, groups must evaluate the payer contracts that create revenue as well as the additional agreements that allocate compensation to the physicians in the practice.