Patients want weight management in primary care, but regular office visits tend to focus on comorbidities, leaving little time to talk about weight.

Fam Pract Manag. 2023;30(6):19-25

Author disclosures: no relevant financial relationships.

Obesity is a critical public health issue that contributes to most of the leading causes of death in the U.S., including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, immobility, and mental illness. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 41.9% of adults in the U.S. have obesity (defined as a body mass index [BMI] of 30 or higher)1 and another 31.1% are overweight (BMI of 25–29.9).2 Many patients would like to lose weight but face barriers such as stigma, demotivation, low self-efficacy, cost, and poor access to care.3 However, recent research suggests that with the right structures to identify and address these barriers, primary care practices can deliver effective obesity care that helps patients lose weight, alleviating comorbidities and improving outcomes without contributing to stigmatizing “fat-shaming.”4–6

We implemented a weight management program for primary care rooted in the fundamental concept of the weight-prioritized visit (WPV). Half of the patients who participated in this model lost more than 5% of their body weight, including one-third who lost more than 10%, and almost one-fifth who lost more than 15%.7 Before implementing this approach, we never seemed to have enough time to address weight management adequately during office visits. The new program prioritizes weight management rather than focusing on obesity's sequelae, creating time for more comprehensive discussions. In a WPV, both patient and clinician understand the visit will be dedicated to talking about weight and co-creating a comprehensive, personalized treatment plan.

Here are five steps to implement a WPV program in your practice.

KEY POINTS

With new options for weight-loss treatment (e.g., medications or bariatric surgery) more patients may be open to weight-management discussions.

Weight-prioritized visits (WPVs) set aside time to discuss the patient's weight journey — time that isn't always available during regular office visits.

Medicare covers behavioral counseling for obesity starting with weekly visits and gradually moving to monthly visits over the course of a year.

1: PREPARE YOUR EHR

Developing the following set of EHR tools can make WPVs more standardized, predictable, and efficient.

Create specific visit types for initial and follow-up WPVs. This ensures patients are scheduled into visits of appropriate length (e.g., 40 or 20 minutes) and denotes whether the visits are in person or via telehealth. Dedicated visit types can also trigger other steps outlined below, such as sending pre-visit questionnaires.

Develop pre-visit questionnaires. This reduces the time the care team spends collecting historical details during the visit. The questionnaires also help patients reflect on their weight history in advance so that visits can focus on high-value activities such as exploring important nuances in the history, counseling, and shared decision-making. (See a sample questionnaire.) Many EHRs can send and receive questionnaires through the patient portal, either actively “pushed” by staff or triggered automatically during electronic check-in. Alternatively, staff can administer the questionnaire during the rooming process. Store completed questionnaires in the EHR to provide a condensed record of the patient's self-reported, longitudinal progress. Referencing the answers or “pulling” them into the WPV progress note can also serve as documentation for a large portion of the visit history.

In what time of life (age range) did you have the most weight gain?

- Childhood

- Adolescence

- Early adulthood

- Mid-adulthood

- Late adulthood

What do you think contributed to weight gain during that period? (Select all that apply.)

- Genetics

- Puberty

- Pregnancy

- Life stressor

- Menopause

- Certain medication(s)

- Abuse

- Other:

Currently, is your weight:

- Increasing

- Stable

- Decreasing

What is your goal for weight loss (in pounds)? _____

What other priorities are making you want to pursue weight management?

- Treat current health problems

- Prevent health problems

- Achieve better functionality

- Other:

How important is it for you to decrease/manage your weight (0% = not important, 100% = very important)? _____

How confident are you in your ability to manage your weight (0% = not confident, 100% = very confident)? _____

Do you take medication (e.g., blood pressure drugs) or use medical devices (e.g., CPAP) to address health consequences of your weight? _____

Do you think your current weight is impacting your health? _____

If you reach your weight-loss goal, how long would you like to maintain it?

- More than 1 year

- More than 5 years

- More than 10 years

- Other:

Why is weight loss and weight-loss maintenance important to you (e.g., energy to play with grandkids, travel)? ___________________________

What is your eating style?

- Vegan

- Vegetarian

- Low carb

- Low fat

- Omnivore

- Intermittent fasting

- Other:

Approximately how many calories do you eat per day? _____

What dietary changes have you tried in the past for weight loss? (Choose all that apply.)

- Calorie restriction

- Fat restriction

- Carb restriction

- Commercial diet plan

- Over-the-counter weight loss products

- Other:

What are your barriers to diet change?

- Cravings

- Hunger

- Cost

- Food access

- Binge eating

- Unknown

- Other:

How much time do you spend doing aerobic exercise (minutes per week)? _____

How much time do you spend doing resistance/weight training (minutes per week)? _____

What are your barriers to doing more physical activity? (Choose all that apply.)

- Time

- Access to facility/equipment

- Lack of instruction

- Pain

- Immobility

- Other:

What gets in the way of you losing weight? (Choose all that apply.)

- Sedentary job

- Overweight spouse/partner

- Cultural pressure

- Lack of social support

- Other:

How often do you eat extremely large amounts of food at one time and feel that your eating is out of control?

- Never

- 1 time per week

- 2-4 times per week

- 5+ times per week

Does your medical insurance pay for anti-obesity medications? _____

Have you ever used anti-obesity medications? _____

Have you ever undergone a bariatric procedure? _____

How confident are you in your health care plan (0% = not confident, 100% = confident)? _____

Configure order sets or preference lists. This makes ordering common obesity-related lab tests, medications, and referrals more efficient and can provide clinical decision support to clinicians who are less familiar with appropriate diagnostics, therapeutics, and locally available referrals. Practices whose EHRs don't have this function can use laminated cheat sheets or pocket cards. Maximizing other existing support tools in the EHR, such as practice alerts and pre-made documentation phrases, can also expedite WPVs. Condition-specific longitudinal reports can track weight, markers of related conditions (such as A1C, blood pressure, and lipids), as well as pain, mood, and function scores.

Embed succinct, fact-based patient education into your EHR. Topics may include nutrition, dieting, physical activity, and medication administration and side effects. These can be either standalone handouts or pre-written phrases you add to a customized treatment plan or after-visit summary.

2: ESTABLISH TEAM-BASED WORKFLOWS AND TRAIN STAFF

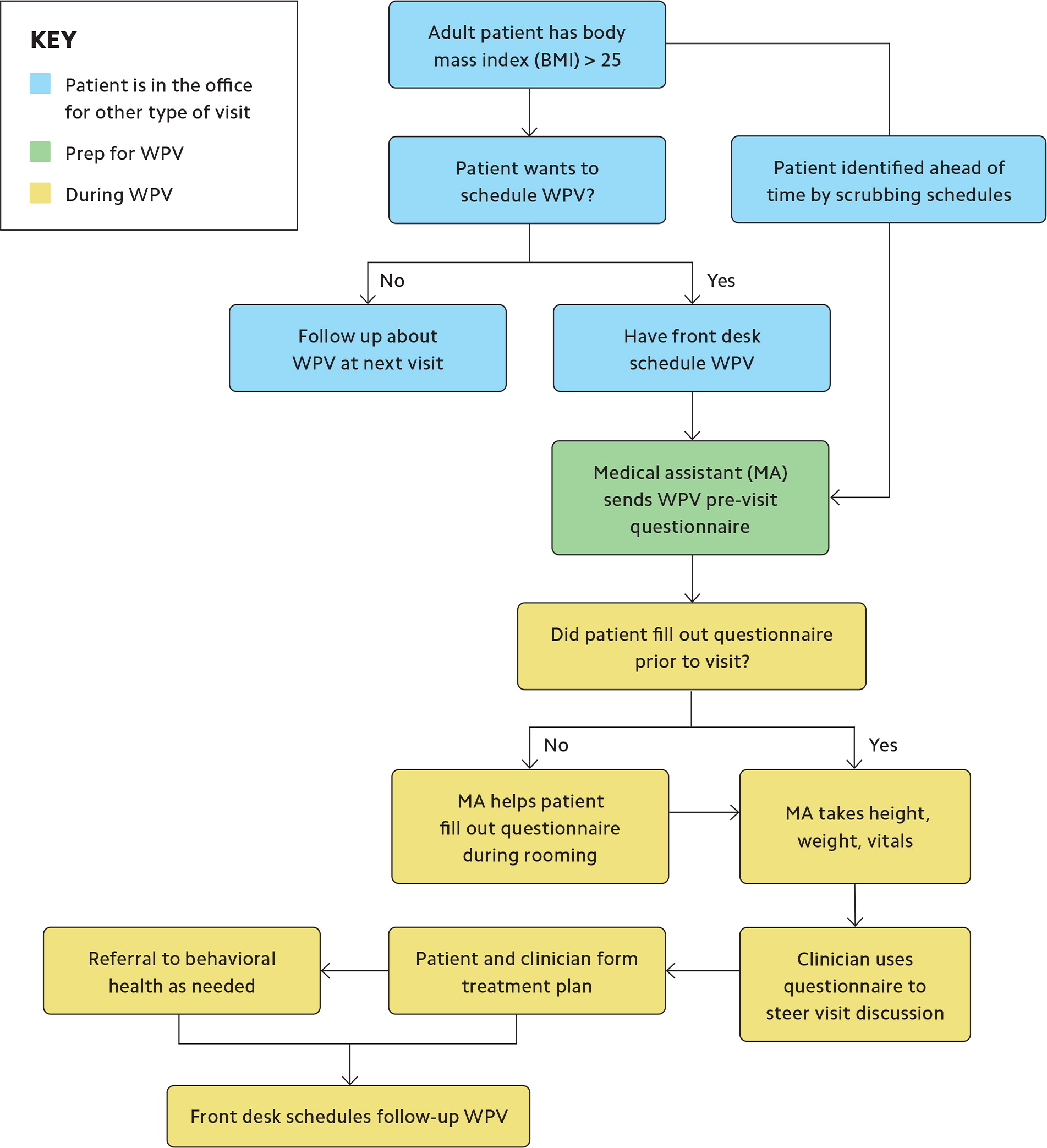

Effective weight management can be time-consuming, especially at the outset and at inflection points such as weight-loss plateaus. Leverage your team members to redistribute the work. Think creatively about who on your team can contribute. For example, front-desk staff can handle WPV scheduling, and any staff member can administer pre-visit questionnaires, whether through the EHR portal, via telephone, or during rooming. (See “Sample workflow for weight-prioritized visit” below.)

Other tasks require more specialized staff members. Behavioral health professionals, if available, can perform behavior change counseling. If they're not available, you can train medical assistants, registered nurses (RNs), care managers, social workers, or peer coaches to use motivational interviewing. You may be able to delegate some medication management tasks to RNs and pharmacists, or use collaborative drug therapy management protocols, depending on your state's rules. Well-defined roles, responsibilities, and workflows provide clarity to staff and help patients understand who is in charge of what part of their care.

Training should ensure that team members understand their roles and responsibilities as well as any EHR processes. Staff and clinicians should understand the pathophysiology of obesity and principles of evidence-based weight management, and they should be trained in destigmatization, cultural competency, and use of inclusive language.6

3: ENGAGE PATIENTS

Engaging patients in weight management can be challenging. They may want help with their weight but feel stigmatized or harbor embarrassment and shame related to prior experiences. They also may have developed learned helplessness after failed attempts to lose weight. This is when active and passive engagement can help.

Active engagement involves capitalizing on teachable moments in day-to-day patient care with a sensitive, inclusive approach. Chronic disease management and annual wellness visits are often good opportunities for this. If patients don't initially welcome or initiate discussions about weight, use the related health concerns they prioritize as an entry point. This approach helps patients develop insight into the connection between excess weight and health outcomes, especially if you focus on both disease-oriented goals (e.g., lower A1Cs, lipids, and blood pressure) and patient-oriented goals (e.g., deprescribing, mobility, endurance, mood, sleep, pain, and functional longevity). For example, you might tell a patient, “What I hear you say is that your knee pain and difficulty managing diabetes have really impacted your ability to do things with your family. Is that right? I'm concerned that excess weight may be contributing to your knee pain and complex diabetes regimen. Would it be OK if we find time to discuss this more?”

When discussing these issues, use person-first language (e.g., “person with obesity” rather than “obese person”) and nonjudgmental terms such as “excess weight” or “adipose tissue.” If the patient agrees to talk about weight management, inform them about the WPV process, during which you will discuss weight specifically and develop a personalized management plan. Patients who are not aware that their weight is an issue, or aware but not sure they want to proceed with treatment for it, may not be ready to schedule a WPV. Document your findings and continue the conversation at future visits if the patient is amenable. Other patients will welcome the opportunity to talk about weight management; schedule them for an initial WPV as soon as possible.

Active engagement can be helpful when you're just starting WPVs because it allows you to control the volume of visits as you refine your office's workflows.

Passive engagement is essentially marketing, and it can be helpful when you're ready to bring a pilot program to scale. It can include displaying promotional materials about your WPV program in the waiting room, hanging posters or flyers in exam rooms, or pushing messages to patients at electronic check-in. The text can be simple: “Are you interested in medical management of your weight? If so, please schedule a weight-prioritized visit.” This approach allows patients to self-select WPVs, which generally brings in those who are motivated and ready for change. When your practice is ready, consider external marketing as well. The publicity surrounding new weight-loss drugs may draw in patients. While it's fine to mention medication as a general weight-loss tool in marketing materials, it's important for patients to understand that WPVs are a more comprehensive approach than just writing a prescription.

4. START CONDUCTING WPVS

We use two types of weight-management visits.

Initial visits are at least 30 minutes in length. This allows adequate time to discuss a patient's weight history, barriers, functional status, risks, and comorbidities, and to review appropriate initial management options. Initial visits often begin with exploring the pre-visit questionnaire. This should include both prior successes and failures, the patient's current diet and physical activity (as a baseline), and short- and long-term goals in their own words. Patients often focus their goals on pounds lost and may need help articulating more meaningful goals. For example, one of our patients' goals was to not need a seat belt extender on airplanes. Use supportive and affirming language and nonverbal communication during these discussions, which can sometimes be emotionally challenging. It may be helpful to educate patients about metabolism and weight-loss physiology and the related challenges they face despite working hard to make changes. Use active listening to stay focused on the patient's journey.

Assess whether the patient has any medical conditions that may contribute to excess weight or prevent weight loss. Common contributing conditions include hypothyroidism, diabetes, mood disorders, sleep apnea, and osteoarthritis. When appropriate, order lab tests and other assessments representing weight-related comorbidities such as thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), hepatic function panel, lipid panel, and A1C, as well as mood questionnaires and standardized pain and function assessments. Consider alternatives to medications that can induce weight gain or prevent weight loss, including certain hypoglycemics, anticonvulsants, contraceptives, steroids, and psychiatric medications. Assessing behavioral health is also an important part of a thorough assessment because mood and eating disorders may play a role in a patient's struggle with weight. For many patients, engaging with integrated or external behavioral health professionals is vital. Even for those without active mental health concerns, behavioral approaches may aid lifestyle changes and provide emotional support during times of discouragement. Finally, identify and evaluate any additional weight-related comorbidities, such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and atherosclerotic disease. This not only gives the patient insight into the full impact of excess weight but also can inform the clinician about indications and contraindications for anti-obesity treatments.

The initial WPV should conclude with the patient and clinician co-creating a personalized, weight-management plan that incorporates the patient's goals. (See “Considerations for patient-specific plans.") It helps to identify some short-term goals to achieve early wins as well as long-term goals. (For more on patient goal-setting, see the related article in this issue.) Once patients establish their goals, help them identify specific changes that may help to achieve them.

CONSIDERATIONS FOR PATIENT-SPECIFIC WEIGHT-LOSS PLANS

Diet. Calories used must be greater than calories taken in to lose weight, but telling patients simply to “eat less” is unhelpful and frustrating. Tailor dietary advice to the patient's situation. Options include modifying food choices rather than decreasing food volume, focusing on what to eat more of rather than less of, or reducing eating time (e.g., intermittent fasting or time-limited eating).

Physical activity. Exercise can help burn calories and build muscle, increasing metabolism and improving appearance; however, it is limited as a standalone strategy for weight loss. Activity is most effective when patients combine it with dietary changes and use it for weight maintenance and prevention of weight regain. Create an exercise prescription that best fits the patient's abilities, is achievable, and addresses barriers. When possible, include moderate-intensity aerobic exercise and resistance/strength training.

Behavioral health. Behavior-based treatment can help modify food intake and address triggers that lead to overeating. Consider engaging with behavioral health, especially when screening identifies a mood- or weight-related eating disorder (e.g., anxiety, depression, binge eating disorder, or nighttime eating syndrome).

Anti-obesity medications. These may be helpful adjuncts to diet and exercise and are approved for those with a BMI ≥ 30, or with a BMI ≥ 27 and obesity-related comorbidities. See the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases resource on prescribing anti-obesity medications.

Referrals to bariatric surgery or a weight management program. Bariatric surgery may be considered for patients unable to achieve significant weight loss with lifestyle changes alone, primarily for those with a BMI ≥ 40, or with a BMI ≥ 35 and weight-related comorbidities. Weight management programs such as Noom or Weight Watchers can be educational and supportive, but they have not demonstrated effectiveness for long-term success.1,2

Identify and discontinue weight-gaining medications. This step is often missed, and such medications may play a significant role in why some patients find weight loss difficult. Identify alternatives whenever possible. See the Obesity Action Coalition's resources on weight-gaining medications.

Follow-up visits should focus on assessing adherence, celebrating successes, evaluating barriers, revisiting goals and expectations, and assessing perceived health status and satisfaction with progress. Conduct a brief comorbidity review to assess changes, specifically improvement or resolution. Follow-up visit lengths may vary depending on the patient's weight management plan and comorbid complexity, as well as primary care clinician availability. Research supports more frequent follow-up visits initially, possibly even once a week.8 If that's not enough time for patients to make identifiable change, consider starting with a two-week interval and then adjust depending on the patient's progress. The interval could also depend on whether the patient is working with others (e.g., behavioral health provider or dietitian), taking weight-loss medication, or facing insurance-related restrictions.

Practices constrained by clinician availability could consider using weight-prioritized group visits to efficiently follow up with more patients.9

STEP 5: GETTING PAID

The most common way to get paid for WPVs is billing an evaluation and management (E/M) code based on either time or complexity (e.g., 99213, 99214, or 99215). To reduce denials by insurance companies that do not cover weight management as a standalone service, list a comorbidity addressed during the visit as the primary ICD-10 visit code, followed by any other relevant comorbidities you discussed, which should be in your documentation. Include obesity as a secondary diagnosis. Note that several ICD-10 obesity codes are associated with Hierarchical Condition Category (HCC) 48 for morbid obesity, including the following:

E66.01, Morbid (severe) obesity due to excess calories,

E66.2, Morbid (severe) obesity with alveolar hypoventilation,

Z68.41-45, BMI 40.0-69.9, adult,

Z68.35-9, BMI 35.0-39.9, adult (if associated comorbidities are present and co-billed).

To receive HCC credit, you must add both the relevant “E” and “Z” ICD-10 codes, and include in your documentation the patient's BMI at the time of service. (For more on HCCs, see the related article in this issue.)

Medicare Part B provides the following coverage for behavioral counseling for obesity:

First month: weekly face-to-face visits,

Months 2–6: every other week face-to-face visits,

Months 7–12: monthly face-to-face visits if the patient meets the 6.6-pound weight-loss requirement at the six-month visit. Document reassessment of obesity and weight loss at this visit before proceeding for an additional six months.10

Use HCPCS code G0447 for 15 minutes with an individual patient and code G0473 for 30 minutes of group counseling (2–10 patients). These codes may not be billed with an E/M code for the same visit. They require patients to have a BMI over 30, so include at least one ICD-10 code documenting that (Z68.30–Z68.39 or Z68.41–Z68.45).

THE TIME HAS COME FOR WPVS

Many factors are aligning in favor of instituting WPVs. Patients want weight management in primary care. Value-based care programs increasingly reward practices that mitigate weight-related complications. New and diverse options for weight management now extend well beyond lifestyle advice to include medications, bariatric surgery, and intensive behavioral therapy. Following our five steps can help practices overcome barriers to weight management and use WPVs to allocate enough time to help patients improve their health.

Start with a nuanced, personalized approach that incorporates humility and empathy and tackles weight stigma. Learn what works together with your patients. Celebrate small wins, and refine your quality improvement processes as you go. As with any new clinical initiative, you will become more effective over time, and your patients will appreciate your efforts.