By taking these five steps, physicians can start changing a culture of medicine that prizes stoic perfectionism and stigmatizes asking for help.

Fam Pract Manag. 2024;31(4):22-26

Author disclosures: no relevant financial relationships.

Rates of alcohol use disorder, depression, and suicidal ideation are all greater among physicians and medical trainees than the general population,1–12 despite education levels and financial resources that insulate physicians from some risk factors such as poverty and lack of access to mental health care. Many of these problems are driven by a medical culture that prizes stoic perfectionism and stigmatizes asking for help.

This article seeks to quantify the problem of physician substance use disorder, depression, and suicide, and then provide steps we can all take to reduce the incidence of these conditions for ourselves and our colleagues.

KEY POINTS

Physicians and medical trainees have higher rates of alcohol use disorder, depression, and suicidal ideation than the general population.

The perfectionist culture of medicine, as well as fears about losing licenses or credentials, may prevent physicians from seeking mental health care.

By speaking up about their own struggles and looking after colleagues, physicians can start to change the culture and increase use of the many mental health care resources available to them.

QUANTIFYING THE PROBLEM

Recent studies suggest that while the misuse of illicit drugs is less common among physicians and medical trainees than the general population, alcohol use disorder is more common.1 About 10% of the U.S. population has alcohol use disorder,2 while surveys indicate the rate may be 32% among medical students3 and 13% among emergency medicine residents.4 Debt and financial instability among students and residents may lead to stress and maladaptive coping through alcohol use.3,4 But the problem persists after training, with both male physicians (13%) and female physicians (21%)1 experiencing higher alcohol use disorder rates than the general population. The sex discrepancy may be related to the disproportionate effect on females of certain risk factors for alcohol use, such as work-home conflict (see “Risk factors for alcohol and substance use disorders among medical trainees and physicians”).5

RISK FACTORS FOR ALCOHOL AND SUBSTANCE USE DISORDERS AMONG MEDICAL TRAINEES AND PHYSICIANS

The culture of medical training and clinical practice may predispose us to these problems. Many of us work long hours, often with the fear of making a mistake hanging over us, all the while feeling like we must suppress our emotions.13 Moreover, the often-crushing debt incurred in medical school creates intense pressure to “power through” and finish training, and then make career decisions that may lead to professional dissatisfaction, working in systems that are highly inefficient and offer little autonomy.14 All of this can position physicians to need help. Fortunately, that help is available, if we empower physicians to seek it.

BUILDING A CULTURE OF WELL-BEING

Seeking help for substance use and mental health needs is slowly becoming more socially acceptable, leading to more accessible services. (See “Mental health resources.") There are now 24-hour mental health talk and text crisis lines, including some created specifically for physicians. Physician health programs are available in every state to facilitate substance use disorder treatment, and many employers have employee assistance programs with free counseling services. Evidence supports better outcomes when physicians receive treatment,15 but many do not seek help due to stigma, risk associated with licensure or training status, and a medical culture that reinforces perfectionism and stoicism.13,15,16

MENTAL HEALTH RESOURCES

Physician-specific resources

Physician Support Line: 888-409-0141 (available 8 a.m. to 12 a.m. ET Monday-Friday)

Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Resources for Reducing Mental Health Stigma

General resources

988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline: call or text 988 (available 24 hours a day, seven days a week)

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) national helpline: 800-662-HELP (4357)

Veterans Crisis Line: call 988 and press 1 or chat online

National Alliance on Mental Illness: 800-950-NAMI (6264); frontline health care professionals can text “SCRUBS” to 741741

It's a daunting problem, but there are steps each of us can take to create a healthier environment for ourselves and our colleagues.

1. Challenge the culture of medicine as it relates to mental health. We can let go of the idea that we must sacrifice our well-being for the sake of our patients, and we can embrace self-care as the best way to ensure our patients get what they need. Our thought process should be something like the advice airline passengers receive: In the event of a loss of cabin pressure, secure your own oxygen mask before helping others.

We can also start changing the culture by being open about our own emotional struggles. This strengthens connections with colleagues and empowers people around us to do the same. Every time we share, it erodes the toxic stoicism and perfectionism that fuel these problems.

2. Advocate for removing credentialing-related barriers. Fear of losing their license or other credentials may prevent physicians from seeking the care they need. The American Medical Association and other groups recommend eliminating antiquated, invasive questions about mental health or substance use (e.g., “Have you ever gone to therapy?”) from licensing or credentialing forms.17 Many states have responded by updating language to query clinicians only about current impairment, with supportive language about getting help and “safe haven” reporting options that allow physicians to avoid reporting a diagnosis or treatment history if they are in a monitoring program.18 But more can and should be done in this regard. Find out the policies in your area and connect with your local AAFP chapter or other medical association to advocate for change.

3. Decrease workplace stress and improve support for clinicians. There are many tools physicians can learn to use to individually manage stress, such as cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness, and cognitive restructuring (see the FPM Physician Burnout & Work-Life Balance topic collection).

But these individual efforts aren't enough for physicians working in a broken system. Organization-directed interventions demonstrate greater impact on physician burnout.19,20 Partnering with leadership in your clinical space to optimize workflows can help you feel empowered and make the system more efficient.21 Physicians can also advocate for evidence-based interventions to help mitigate burnout, which is associated with substance use, depression, and suicide. These include reducing administrative burden, offering well-being assessments, and providing access to confidential treatment.

4. Build connections and community in the workplace and at home. Burnout, substance use, depression, and suicidal ideation all feed on isolation. Studies show the protective effects of community and social support for residents and physicians.3,4 We can take steps to create connections with our colleagues, develop a sense of community in our workplaces, and reinforce our network of family and friends. (See “Creating Intentional Professional Connections to Reduce Loneliness, Isolation, and Burnout," FPM.)

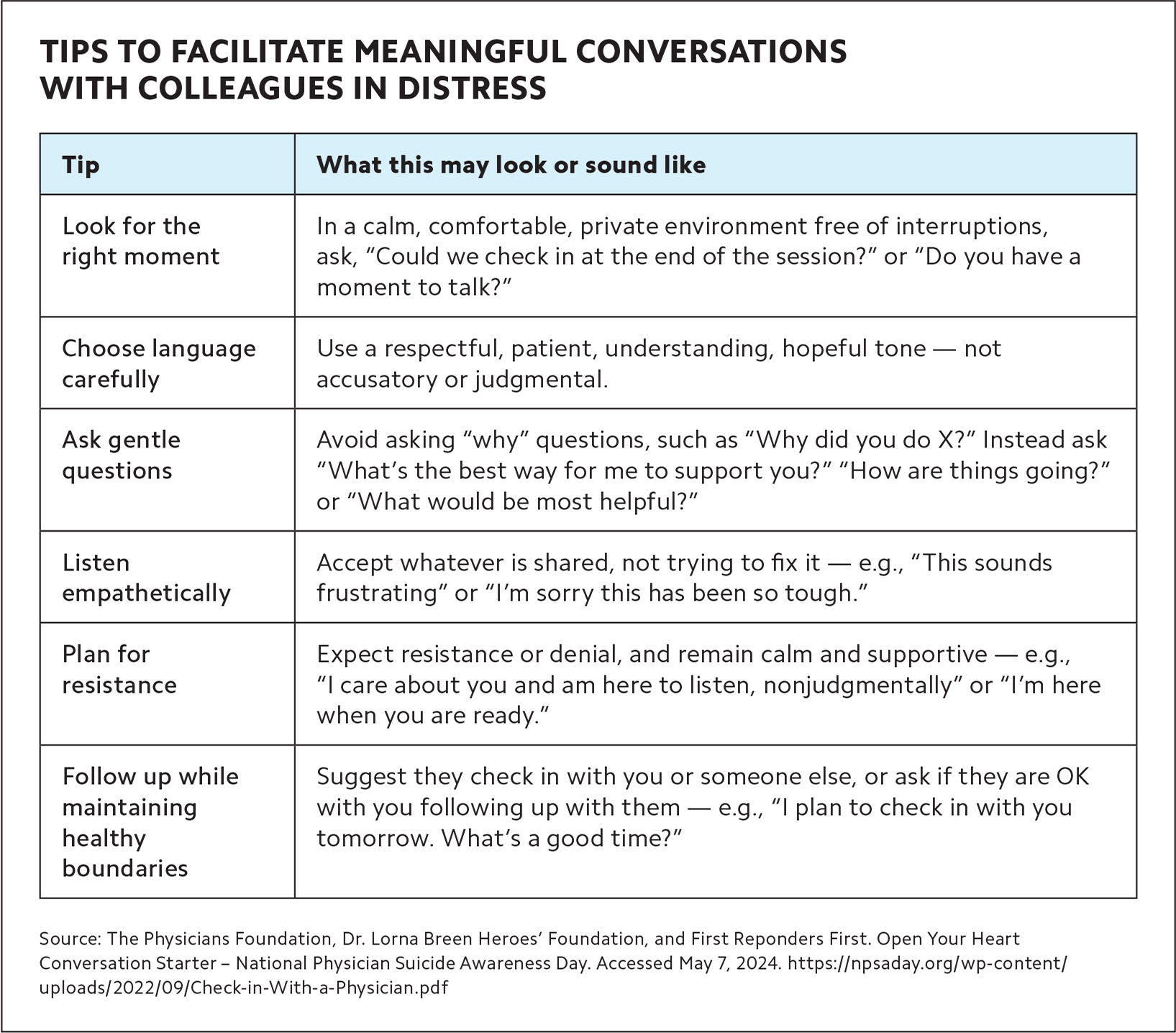

5. Say something. The culture that encourages physicians to suffer in silence can be unraveled by the simple act of saying that we notice, we care, and we want to help a colleague who is hurting. Knowing what to say is often difficult in these situations, but the tips below provide examples. A meaningful conversation at the right time may help save your colleague's life.

| Tip | What this may look or sound like |

|---|---|

| Look for the right moment | In a calm, comfortable, private environment free of interruptions, ask, “Could we check in at the end of the session?” or “Do you have a moment to talk?” |

| Choose language carefully | Use a respectful, patient, understanding, hopeful tone — not accusatory or judgmental. |

| Ask gentle questions | Avoid asking “why” questions, such as “Why did you do X?” Instead ask “What's the best way for me to support you?” “How are things going?” or “What would be most helpful?” |

| Listen empathetically | Accept whatever is shared, not trying to fix it — e.g., “This sounds frustrating” or “I'm sorry this has been so tough.” |

| Plan for resistance | Expect resistance or denial, and remain calm and supportive — e.g., “I care about you and am here to listen, nonjudgmentally” or “I'm here when you are ready.” |

| Follow up while maintaining healthy boundaries | Suggest they check in with you or someone else, or ask if they are OK with you following up with them — e.g., “I plan to check in with you tomorrow. What's a good time?” |

CHANGE IS POSSIBLE

The tragic death of Lorna Breen, MD, in April 2020 brought national attention to the issue of physician well-being. Breen, who was medical director of the New York Presbyterian Emergency Department in New York City, suffered severe fatigue after contracting COVID-19 and died by suicide.22 Her death led to a foundation in her name dedicated to fighting for the professional well-being and mental health of health workers. Two years after Breen's death, Congress passed the Dr. Lorna Breen Health Care Provider Protection Act, which directs the federal government to provide grants and develop programs to promote mental health among medical professionals.

Change like that comes from people like us — physicians advocating for the well-being of ourselves and our colleagues. Let's begin caring for ourselves and each other by speaking up in the right way at the right time.