Systemic obstacles set up patients to fail. By addressing three specific areas, we can make adherence easier and help patients achieve better health outcomes.

Fam Pract Manag. 2024;31(4):27-31

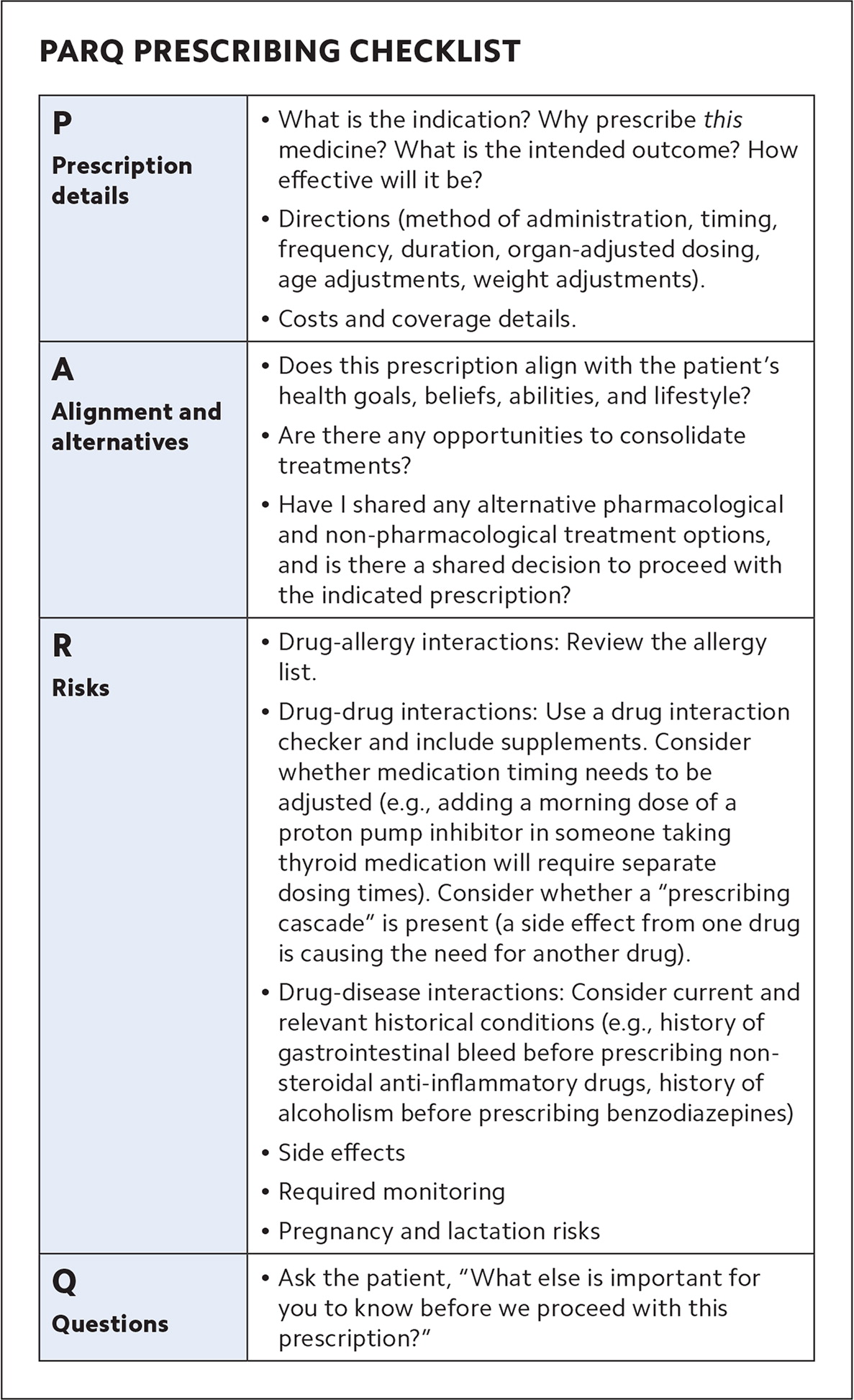

Tool: PARQ prescribing checklist

Author disclosures: no relevant financial relationships.

The first time I (Dr. Larson) reviewed Ms. D's chart, I was stunned by her nearly weekly visits to the emergency department. Her problem list stretched on and on, including diagnoses of falls, hypokalemia, edema, confusion, chronic back pain, history of polysubstance abuse, anxiety, and hypertension. A review of her medications revealed the cause of many of her issues: an overwhelming combination of muscle relaxants, gabapentin, multiple antihypertensives, antiemetics, and two serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). During our weekly visits, we slowly unraveled the tangle of medications and their interacting effects. One antihypertensive was contributing to edema, which had led to the addition of a diuretic that contributed to hypokalemia — a prescribing cascade1 that caused the patient direct harm.

Duplicative SNRI therapies for different indications (back pain and anxiety — one prescribed by a psychiatrist and another by primary care) had caused serotonin syndrome, leading to elevated blood pressure, falls, and worsened anxiety. To mitigate the anxiety, Ms. D had taken benzodiazepines and opioids left over from previous prescriptions, leading to another fall. Labeled in her chart as “non-compliant,” she had actually attempted to adhere to a drug regimen that was causing harm. Flawed medication reconciliation and refill workflows, along with a lack of communication across specialties, further complicated the care of her already complex physical and mental health needs.

Many studies on medication adherence examine individual patient factors such as beliefs about medications, cognition, health literacy, language, social factors, and cost.2–4 But as prescribers, we should also scrutinize the care structures and delivery systems that make adherence difficult even in the best of circumstances. This article offers tips for driving improvement in three specific areas: 1) medication reconciliation, 2) information sharing between pharmacies and physicians, and 3) the prescribing process.

KEY POINTS:

Thorough medication reconciliation practices, clinical communication with pharmacies, and vigilance in the prescribing process can help patients understand and adhere to safer medication regimens.

Consider an annual, focused, and detailed medication review where patients bring their physical medications (rather than just a list) to the clinic, or schedule a virtual visit so the patient will have the medications on hand.

Prescribing is a multifaceted process that includes shared decision making with patients. Consulting a pharmacist and using a checklist can be helpful, particularly for patients experiencing polypharmacy.

MEDICATION RECONCILIATION

Without a single “source of truth” about what medications the patient is taking, we have no way to educate patients or help them adhere to recommended treatment. Medication reconciliation is essentially a two-step process: compare the medications listed in the patient's chart to what the patient is currently taking, and then compare that to what the patient should be taking. Well-intended prescribing can misfire, particularly during care transitions, such as changes in drug dosages between visits to primary care physicians and other specialists, and from hospital to home.

Reconciliation requires a systematic, comprehensive review of a patient's medications5 performed by a pharmacist, clinician, or other qualified health care team member. The process often relies on patient recall of hard-to-pronounce drug names and dosages, rather than the natural cues patients rely on at home, such as medication shape and color. Multiply that recall process times 20 medications from multiple prescribers, and the task is daunting. Including non-prescription medications and supplements (often difficult to classify precisely within EHRs) as well as medications the patient has in their possession but is not presently taking (though they want to keep on hand “just in case”) adds to the complexity.

The following tips can help with the reconciliation process.

Complete a detailed medication review annually. While many patients maintain lists of their medications (which can be helpful in history-taking), medication reconciliation ideally includes a physical review of each medication with the patient. We recommend that practices dedicate one visit a year to this process. Some patients with Medicare Part D qualify for the Medication Therapy Management program,6 which covers a comprehensive review of medications by a physician or clinical pharmacist with no cost-sharing.

Asking patients to bring their pill bottles to a visit also presents an opportunity to see how they are managing their medications: Are they consolidating different pills into a single bottle? Are they correctly filling a pillbox? Do they still have medications that the prescriber intended for them to stop taking months ago?

As an added step, consider contacting the patient's pharmacy (or pharmacies) for a 12-month medication fill history that you can review with the patient. The patient's pharmacy will often have the most comprehensive list of medications, especially for patients who see multiple specialists. Having this list and the patient's pill bottles makes for the most effective visit: You can compare what the patient has been prescribed with what they're taking (and when and how they're taking it) to make sure everything matches.

Virtual visits can also be helpful, especially for patients who forget to bring their medications to the clinic. Patients can sometimes review a list of their prescribed medications on their electronic portal as part of the visit. You can have them hold their pill bottles up to the camera to identify their medications, or use a resource such as WebMD's Pill Identifier for loose pills.7

As you curate the patient's master medication list, group medications by indication (e.g., blood pressure medicines and diabetes medicines) if possible, rather than alphabetical order (the default in most EHRs). This will help you connect the patient's medications with their active conditions and better manage the list going forward.

Reconcile medication lists at every visit. Outside of the annual medication-review process, ongoing reconciliation should take place at the end of every visit by removing any medications you recommended the patient stop taking and ensuring any new prescriptions were added to the list and sent to the correct pharmacy. A medical assistant may help with this discharge process and final check. Give the patient a new version of their medication list in print or electronically (e.g., through the portal) and advise them to take any discontinued medications to their pharmacy or other authorized drug collection site for proper disposal.

Have clinical staff gather data between visits. Reconciliation can also take place outside of office visits, such as when a patient sends a message through an electronic portal, calls the clinic, or transitions from the hospital. Empowering your nurses and medical assistants to update the medication list with patient-reported changes during these interactions will make the work of in-visit reconciliation much easier. Some EHRs also facilitate “outside medication reconciliation,” through which data from other prescribers can be sent directly from their EHR to yours. The information is not automatically integrated into your medication list, but you can add the integration process to your clinical staff's workflow as well.

Standardize roles, processes, and expectations. In health systems where multiple physicians contribute to the same patient record in the EHR, it is helpful to develop a consistent reconciliation process that facilitates information sharing across specialties and settings. For example, an orthopedic surgeon may be reluctant to remove an antihypertensive drug from the patient's medication list if the primary care physician prescribed it but the patient reports no longer taking it. A standardized notation on the medication list can help signal to the other physician to review this in more detail with the patient at the next visit. Physicians can also notate that a medication was “prescribed by rheumatology,” for example, to indicate who “owns” a particular prescription. If changing a patient's medication regimen will affect another physician's plan of care, physicians should also send their notes to the other physician. (Some of the principles for updating and sharing patient problem lists in the FPM article “Taming the Problem List” may also be applicable to updating and sharing medication lists.8)

INFORMATION SHARING BETWEEN PHARMACIES AND PHYSICIANS

The goal for information sharing between pharmacies and clinics is to reduce polypharmacy and other medication problems, such as harmful drug interactions. Some EHRs send “fill data” from pharmacies to clinics (similar to state-sponsored prescription monitoring systems for controlled substances), so physicians can tell whether patients have filled their prescriptions. This can assist the reconciliation process on the clinic side. Some EHRs also transmit medication discontinuation instructions from clinics to pharmacies, but often this isn't sufficient to allow pharmacists to fully assist in medication management.

Ideally, physicians should not only share each change to a medication regimen with the patient but also document it in the EHR and transmit it electronically to the pharmacist for the next fill. You can use the “comments” section of the e-prescription, which is not included in the medication labeling for the patient, to briefly communicate clinical intent to the pharmacist. An EHR macro can facilitate easy documentation such as “dose change due to X,” “tapering off medication,” or “replacement for X medication.” Because the pharmacist is considered a direct participant in the patient's care, you can also share office notes with them as needed in compliance with HIPAA. Unfortunately, few retail pharmacies can store this information within their own electronic systems. In those instances, sending the patient to the pharmacy with a paper copy of the visit summary and end-of-visit medication list may be helpful. This equips the pharmacist to assess the medication change and tailor education to the patient. It also may save time for everyone involved, as it limits back-and-forth faxing or phone calls when a pharmacist requires more information before they can safely dispense a medication.

THE PRESCRIBING PROCESS

Clinicians and patients alike can underestimate the multifaceted decision-making process of prescribing and the time it takes to do it safely and thoroughly, especially for patients who are elderly or have a high chronic disease burden. Clinicians must consider allergies, drug-drug interactions, drug-disease interactions, antibiograms, drug clearances, and the balance of harms and benefits, in addition to adherence factors such as insurance coverage, cost, tolerability, ease of the dosing schedule, and social determinants of health.

Technology has simplified some of this due diligence, but device-alert fatigue, ambiguity, high workload, and time pressure can still cause prescribers to breeze past important variables. Best-practice alerts, patient expectations, and pay-for-performance incentives can also pressure clinicians to hit “send” on prescriptions before sufficiently evaluating them.

To force a necessary slowdown, use a checklist before prescribing (see “PARQ prescribing checklist”) and use point-of-care drug references to check medication details. (Lexicomp, Micromedex, and Epocrates are useful general online drug references but require subscriptions. For clinicians who treat breastfeeding patients, LactMed and Medications and Mothers' Milk by Thomas Hale are helpful. For patients 65 and older, consider using the Beers Criteria published by the American Geriatrics Society.) You might even be able to step out of the visit briefly and talk to a pharmacist about a medication or consult another resource before prescribing it, if necessary. When the patient knows you are doing this for their safety and benefit, they typically will appreciate it.

| P Prescription details |

|

| A Alignment and alternatives |

|

| R Risks |

|

| Q Questions |

|

WORKING TOGETHER FOR BETTER ADHERENCE

If we expect patients to take their medications as prescribed, we must prescribe what we, together with our patients, agree they should take. Irreconciled medication lists, lack of coordinated communication between prescribers and pharmacists, and failure to adequately scrutinize drug profiles and interactions during the prescribing process can leave patients in worse health. We must address these systemic challenges if we want to see improved safety and greater patient adherence to their medication regimens.