Understanding common challenges, promising models, and potential partnerships can help you choose the best path forward.

Fam Pract Manag. 2025;32(1):21-27

Author disclosures: no relevant financial relationships.

Value-based payment (VBP) arrangements have been championed by policymakers and payers as a way to improve patient outcomes while reducing overall costs, in part by supporting the high-value care that primary care physicians provide. VBP models better support the delivery of cognitive services, such as care coordination and chronic disease management, completed largely outside the 15-minute office visit and not adequately captured in fee-for-service (FFS) reimbursement. FFS payments do not fully support the teams and systems necessary to provide comprehensive primary care in the context of a longitudinal patient relationship, which produces better health outcomes at lower costs.1 Instead, FFS puts primary care physicians on a hamster wheel of rapid visits, documentation, and billing.2

When properly structured, VBP arrangements recognize that value by providing up-front payments for each patient on a physician's panel and potential shared-savings payments. As an illustrative example, it is estimated that one current group of 10 primary care physicians that influences almost $100 million in health care spending can reap the benefits of up-front payments and fewer administrative burdens in the VBP arrangement it participates in.3

The financial investment necessary to succeed in VBP arrangements largely depends on the practice and its current infrastructure.4 Practices must consider the costs and benefits of individual VBP models and leverage available resources. This article provides an overview of the barriers to VBP participation, primary-care-focused VBP models, and key considerations for establishing partnerships to support this transition.

KEY POINTS

Independent practices face challenges in transitioning to value-based payment (VBP) models, including capacity constraints, financial risk, care for complex patients, delayed payments, and lack of commercial payer participation.

The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation is piloting several promising VBP models that address these challenges, in part by offering prospective payments.

To successfully transition to VBP, independent practices may need to partner with entities such as VBP enabler organizations, clinically integrated networks, or independent practice/physician associations, which can help provide the necessary infrastructure, technical assistance, and financial support.

BARRIERS TO VBP PARTICIPATION

Transitioning to VBP can feel daunting, particularly for small or independent practices. Common barriers include the following:

Capacity: The effort needed to succeed in VBP models includes understanding quality reporting obligations, modifying clinical models and workflows, and building out needed staffing, technology, and other infrastructure — which requires an investment of time and money. Many practices need assistance to increase their capacity for this work.

Financial risk: Practices may lack the capability to assess the impact of taking on financial risk for the care outcomes of their patient population, which will ultimately determine their success in VBP arrangements.5 This can be especially challenging in markets or models that require practices to take on risk more rapidly.

Care of complex patients: Certain characteristics in a patient population can make it more challenging to take on financial risk. As a result, practices in areas of high social vulnerability, or that serve more complex patients, must carefully consider how and whether to participate in VBP models.6

Delayed payments: While the most advanced VBP models provide prospective payments, many models take 18 months or longer to distribute shared savings, making it difficult for practices to develop capacity and infrastructure as well as to generate the necessary cash flow to support staff.

Lack of commercial payer participation: While commercial payers continue to increase use of VBP arrangements,7 a lack of sufficient engagement (and revenue) from commercial payers can still be a barrier to practices making necessary care delivery changes.8 Just 4.1% of commercial payments in 2022 were linked to the most sophisticated VBP models (population-based payments) versus 9.8% for traditional Medicare and 24.6% for Medicare Advantage.7

VBP MODELS WITH SUBSTANTIAL PRIMARY CARE FOCUS

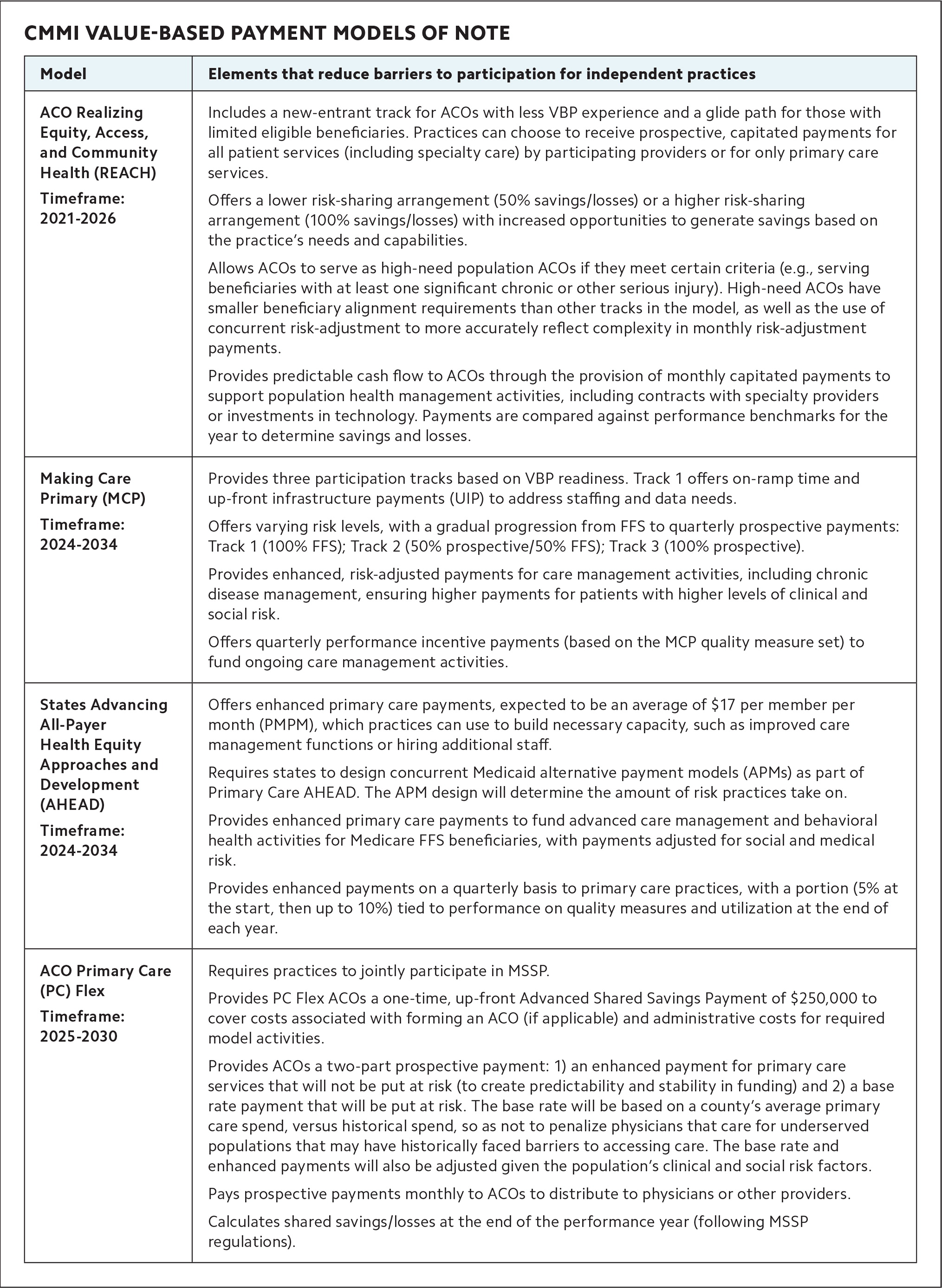

The Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation (CMMI) is conducting several VBP demonstration projects that address these barriers and include design elements to support small or independent primary care practices.9 These VBP models are implemented either at the practice level or through participation in an accountable care organization (ACO). They typically apply to Medicare populations; however, CMMI is working to align elements (e.g., quality reporting requirements) across payers to reduce burden and accelerate VBP adoption across the health care system. Not all practices are eligible to participate in all models (some are limited to certain states or accept a finite number of participants), but they are promising models to watch nonetheless. The table below provides more detail on the following models.

ACO Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health (REACH) launched in 2021 and will continue through 2026. CMS has not yet indicated whether the model will continue past its scheduled expiration date, but it generated $1.6 billion in gross savings and $695 million in net savings in 2023.10 It allows ACOs with less VBP experience or limited eligible beneficiaries to participate at varying risk levels, based on their needs and capabilities, and to receive predictable cash flow through monthly capitated payments to support population health management activities.11

Making Care Primary (MCP) launched in July 2024 and will continue through the end of 2025. (Editor's note: CMS announced March 12, 2025, that the program, previously scheduled to end in 2034, would end early.) It allows practices with varying levels of VBP experience to receive prospective payments for their services and build the necessary infrastructure to improve specialty care integration and improve care for people on Medicare and Medicaid. The model includes only Medicare-enrolled practices with a majority of their primary care sites located in one of eight participating states (Colorado, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, and Washington).12

States Advancing All-Payer Health Equity Approaches and Development (AHEAD) launched in 2024 and runs through 2034. It is a state-based model focused on total cost of care that aims to reduce cost growth and improve population health. It includes a primary care pathway that provides enhanced prospective payments for practices.13 So far, six states (Connecticut, Hawaii, Maryland, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont) have been selected.

ACO Primary Care (PC) Flex begins in 2025 and will run through 2030. It is focused on increasing Medicare Shared Savings Program (MSSP) participation among low-revenue ACOs in rural and under-served areas, which are often smaller or physician-led. The model will test how prospective payments and increased funding for primary care services can improve care.14

It is important to note that opportunities to enter into VBP arrangements can extend beyond CMMI models, as commercial payers also provide opportunities for participating practices to engage in VBP. Each payer will vary slightly in the design of VBP arrangements they offer for practices.

CMMI VALUE-BASED PAYMENT MODELS OF NOTE

| Model | Elements that reduce barriers to participation for independent practices |

|---|---|

| ACO Realizing Equity, Access, and Community Health (REACH) Timeframe: 2021–2026 |

Includes a new-entrant track for ACOs with less VBP experience and a glide path for those with limited eligible beneficiaries. Practices can choose to receive prospective, capitated payments for all patient services (including specialty care) by participating providers or for only primary care services. Offers a lower risk-sharing arrangement (50% savings/losses) or a higher risk-sharing arrangement (100% savings/losses) with increased opportunities to generate savings based on the practice's needs and capabilities. Allows ACOs to serve as high-need population ACOs if they meet certain criteria (e.g., serving beneficiaries with at least one significant chronic or other serious injury). High-need ACOs have smaller beneficiary alignment requirements than other tracks in the model, as well as the use of concurrent risk-adjustment to more accurately reflect complexity in monthly risk-adjustment payments. Provides predictable cash flow to ACOs through the provision of monthly capitated payments to support population health management activities, including contracts with specialty providers or investments in technology. Payments are compared against performance benchmarks for the year to determine savings and losses. |

| Making Care Primary (MCP) Timeframe: 2024–2025 (was previously 2034) |

Provides three participation tracks based on VBP readiness. Track 1 offers on-ramp time and up-front infrastructure payments (UIP) to address staffing and data needs. Offers varying risk levels, with a gradual progression from FFS to quarterly prospective payments: Track 1 (100% FFS); Track 2 (50% prospective/50% FFS); Track 3 (100% prospective). Provides enhanced, risk-adjusted payments for care management activities, including chronic disease management, ensuring higher payments for patients with higher levels of clinical and social risk. Offers quarterly performance incentive payments (based on the MCP quality measure set) to fund ongoing care management activities. |

| States Advancing All-Payer Health Equity Approaches and Development (AHEAD) Timeframe: 2024–2034 |

Offers enhanced primary care payments, expected to be an average of $17 per member per month (PMPM), which practices can use to build necessary capacity, such as improved care management functions or hiring additional staff. Requires states to design concurrent Medicaid alternative payment models (APMs) as part of Primary Care AHEAD. The APM design will determine the amount of risk practices take on. Provides enhanced primary care payments to fund advanced care management and behavioral health activities for Medicare FFS beneficiaries, with payments adjusted for social and medical risk. Provides enhanced payments on a quarterly basis to primary care practices, with a portion (5% at the start, then up to 10%) tied to performance on quality measures and utilization at the end of each year. |

| ACO Primary Care (PC) Flex Timeframe: 2025–2030 |

Requires practices to jointly participate in MSSP. Provides PC Flex ACOs a one-time, up-front Advanced Shared Savings Payment of $250,000 to cover costs associated with forming an ACO (if applicable) and administrative costs for required model activities. Provides ACOs a two-part prospective payment: 1) an enhanced payment for primary care services that will not be put at risk (to create predictability and stability in funding) and 2) a base rate payment that will be put at risk. The base rate will be based on a county's average primary care spend, versus historical spend, so as not to penalize physicians that care for underserved populations that may have historically faced barriers to accessing care. The base rate and enhanced payments will also be adjusted given the population's clinical and social risk factors. Pays prospective payments monthly to ACOs to distribute to physicians or other providers. Calculates shared savings/losses at the end of the performance year (following MSSP regulations). |

EVALUATING POTENTIAL PARTNERS FOR TRANSITIONING TO VBP

For many independent practices, the first step in transitioning to VBP is to form or join an ACO. An ACO is a group of doctors, hospitals, or other providers that contracts with a payer to improve health outcomes and reduce costs for a defined population (often a minimum of 5,000 patients) and to share in any savings. Compared with hospital-led ACOs, physician-led ACOs have proven more successful in generating savings and reducing costs.15

Beyond joining an ACO, many practices need additional support. On their own, practices may not have VBP expertise, broad-scale experience in population health management and care coordination, or the financial reserves to make needed investments. Therefore, to successfully participate in VBP models, practices may need to partner with VBP enabler organizations, clinically integrated networks (CINs), or independent practice/physician associations (IPAs). The table below summarizes key aspects of each partnership and key questions to ask before selecting one.

KEY ASPECTS OF VBP PARTNERSHIPS AND KEY QUESTIONS TO ASK

| Entity | Care management services and coordination support | Practice autonomy in clinical pathways and protocols | Practice control of shared savings and incentive payments |

|---|---|---|---|

| VBP enabler organizations | ✓ | ||

| Clinically integrated networks | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Independent physician/practice associations | ✓ | ✓ |

Key questions to ask when selecting a VBP partner:

Autonomy: What level of practice autonomy would you like to retain, and how much autonomy does the potential partner organization provide?

Technology: What is the learning curve of adopting a new EHR system or other required technology? Does the potential partner provide software that can be embedded into an existing technology platform, or will your practice need to implement a new system?

Data: What data are available to you upon joining the potential partner organization? Is there timely information-sharing and access to data among practices in a particular contractual arrangement?

Expert assistance: What is your interest and willingness to work with external coaches or technical assistance experts to shape your practice to enhance efficiency in VBP arrangements?

Payments: Where will shared savings payments or bonuses go once payments are dispersed? What percentage of any payments will be available to reinvest in your practice to further enable team-based versus going to management entities or to sustain the practice's administrative needs?

VBP enabler organizations provide infrastructure, up-front capital, risk-sharing support, population health management tools, payer engagement, and technical assistance to practices. More than 100 different types of enabler entities exist today, with different focuses and approaches, including groups like Aledade, agilon, Equality Health, Pearl Health, and Evolent.16,17 They are generally for-profit entities and aim to attract physicians who wish to remain independent yet lack the capacity to effectively implement a VBP model alone. Enablers will, to varying degrees, provide technical assistance to support practices in modifying their workflows and services to better position them to succeed in VBP arrangements.17

Some enabler organizations support independent practices in building physician-led ACOs or partner with ACOs and practices to support participation in VBP arrangements, such as the ACO REACH model. Enabler organizations may also provide practices with population health management tools that complement a practice's existing electronic health record (EHR) platform to provide data analyses and real-time care management support for patients.18 Some enablers pursue longer time horizons, with one entity we know of signing practices to a 20-year contract under which they bear the risk, in return for recouping 60% of savings generated by the partnership with the practice. This model commits a pool of funding to be used for practice investments, with both the practice and enabler having equal say in how the dollars are spent.17

CINs bring together similar types of physicians or other providers by integrating clinical and other data across participating practices to support patient care management. CINs may include multiple specialties and can facilitate payer contracts on behalf of the entire network. Specific requirements vary, but CINs generally require participating practices to meet certain quality standards and develop IT capabilities to allow for data-sharing and analysis. A CIN can serve as the foundational entity to build an ACO and enter into a VBP arrangement.

In contrast to enabler organizations, CINs are typically nonprofit organizations owned and operated by physicians or other providers and health systems in a specific region and typically limit services to that region. CINs must allow practices to contract with payers outside the CIN if they choose.19 Practices interested in the CIN option could either look for existing CINs operated by hospitals, primary care associations, or others in their area (if available) or band together with other practices similar to theirs to form their own CIN. Practices should be aware that the process of ensuring CIN participants are aligned on shared objectives, management, and data analysis capabilities (e.g., EHR system alignment) can be resource intensive.

IPAs vary geographically, with the majority located in California.20 While it is difficult to quantify the exact number of IPAs nationally, they have become a larger presence in the VBP space. IPAs are not limited to primary care, and their size and scale can vary significantly, with some consisting of practices in a specific region of a state and others spanning states and having thousands of affiliated physicians.21 Notably, an IPA can opt to join a CIN. A key benefit of joining an IPA is that the entity assumes and aggregates risk for health care expenditures, reducing the financial risk individual practices take on. Additionally, an IPA increases a practice's negotiating power when entering into VBP arrangements.

HYPOTHETICAL USE CASE

An independent practice serves a population that primarily consists of Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. It has three physicians, one nurse, two medical assistants, and two administrative staff, and it operates on a tight budget with low margins. The practice would like to enter a VBP arrangement that prioritizes investment in longitudinal care management support for its patient population. However, practice leaders are concerned about meeting and reporting performance benchmarks and satisfying care management requirements in order to realize shared savings and avoid making downside risk payments back to payers.

If the practice wanted a significant level of support in this transition in exchange for a lower percentage of shared savings, it could partner with an enabler organization. Initially, the enabler would take on all downside risk and deploy a practice performance manager to work with the practice and help it build expertise in meeting reporting requirements, transition to population health monitoring software, and develop workflows to engage hard-to-reach beneficiaries and maximize impact under the new arrangement. The enabler would negotiate with payers (including potentially joining MSSP and negotiating with Medicare Advantage and Medicaid managed care organizations) on behalf of the practice and receive a portion of the revenue earned. The enabler would provide access to its own integrated mobile platform for patients and clinicians, which includes claims and population health data analyses, and a community health worker based in the area to assist high-risk patients with care navigation.

Alternatively, if the practice hoped to keep a larger percentage of the shared savings revenue at the cost of greater time and energy invested by the practice staff, it could use a more hands-off, two-pronged approach. First, it could join a regional IPA that negotiates with payers to secure favorable contracts, which costs the practice a small fee, though it is eligible for quality bonuses through the IPA as well. Second, it could join a CMMI primary care model on its own. It could either join an ACO through its IPA and participate in a model like PC Flex that offers enhanced payments or participate in the AHEAD model, if available in its state. In either case, the model would provide up-front payments and infrastructure dollars to support the purchase of population health software and invest in training a new team member to serve as a community care navigator and support quality reporting.

Finally, the practice could determine the feasibility of joining a CIN, if available in the surrounding area. Joining a CIN could support the practice through contract negotiations similar to an IPA, in addition to driving performance improvement and care coordination through integrated IT. However, the practice would need to ensure it is equipped to meet CIN participation criteria, which may include tying performance incentives to compliance efforts.

THE PATH FORWARD

The journey to VBP can be challenging. Understanding your practice's needs, promising VBP models, and the pros and cons of key partnerships can help you make an informed decision about the best path forward for your practice and your patients.