Fam Pract Manag. 2025;32(4):33-36

This content was made possible, in part, by an independent grant from Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. and Eli Lilly and Company who provided financial support for the Program. The publication of this content is brought to you by the AAFP. Journal editors were not involved in the development of this content.

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is defined as “abnormalities of kidney structure or function, present for a minimum of [three] months, with implications for health.”1 Although more than one in seven adults in the United States have CKD,2 a 2023 survey of American adults found that 58% of respondents were unfamiliar with the disease.3 Many people are unaware they have CKD until it has already progressed to an advanced stage. As the U.S. population ages, more adults will be living with the disease. Family physicians play an important role in increasing patients’ awareness of CKD, its key risk factors, and the availability of effective treatments that can slow disease progression, improve quality of life and reduce CKD-related complications.

Chronic disease management in the family medicine setting is more challenging today than ever before. More than half of adult patients in the United States have at least one chronic condition, and 40% have two or more chronic conditions.4 Estimates suggest that primary care physicians would need more than seven hours per day to fully address their patient panel’s chronic disease care needs.5 Efficient, effective chronic disease management requires a coordinated, systematic approach.

CKD Screening Recommendations for Patients With Diabetes

Diabetes mellitus and hypertension are the most common causes of CKD in the United States,6 with approximately one in three adults with diabetes and one in five adults with hypertension affected by the disease.2 Consensus statements based on recommendations from the American Diabetes Association and Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes state that all patients with diabetes mellitus should be screened for CKD using two measures: estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and urinary albumin/creatinine ratio (uACR).7 For people with type 2 diabetes, screening for CKD should start at diagnosis. For people with type 1 diabetes, it should start five years after diagnosis. Testing should be performed at least annually and may be repeated more frequently if results are abnormal. Point-of-care testing now allows for immediate results.1

Decreased eGFR and elevated protein excretion in the urine are strong markers of CKD and increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in patients with diabetes mellitus.8 Optimal screening would occur with the first urine void in the morning.7 However, conducting opportunistic screening at the patient’s convenience may help to ensure that recommended uACR testing is performed.

Despite the high prevalence of CKD in the United States, approximately 90% of people with the disease do not know they have it.2 When patients are diagnosed with CKD, family physicians should take a patient-centered communication approach and explain the condition in clear, straightforward language. They should also highlight that it is often possible to slow CKD progression. With timely interventions, most patients can avoid serious complications and will not require kidney replacement therapy (KRT), which is also known as renal replacement therapy.

While screening for CKD with eGFR has been widely adopted, less than half of people with diabetes and hypertension receive recommended uACR testing.9

Treatment Recommendations for Patients With CKD and Diabetes

Treatment of hypertension and hyperglycemia to goal levels is a top priority in helping people manage CKD. Specific agents have been shown to be protective in diabetes-related CKD.

TREATMENT OF HYPERTENSION

Hypertension treatment starts with proper measurement of blood pressure, including ambulatory blood pressure monitoring at home. These readings are the most predictive of true blood pressure readings. Patients who have CKD and either diabetes, hypertension or albuminuria should be prescribed an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI) or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) unless there is a contraindication.10 It is important to note that these medications should be titrated up to the maximum tolerated dose. Patients should receive laboratory monitoring within two to four weeks of initiation or titration, with specific attention to serum creatinine and potassium.10,11 The normal initial response to an ACEI or ARB will be a slight reduction in eGFR, which can raise the patient’s serum creatinine but will resolve over time. However, if serum creatinine increases more than 30% from baseline or potassium increases to 5.5 mEq per L or greater, stopping the ACEI or ARB should be considered.10

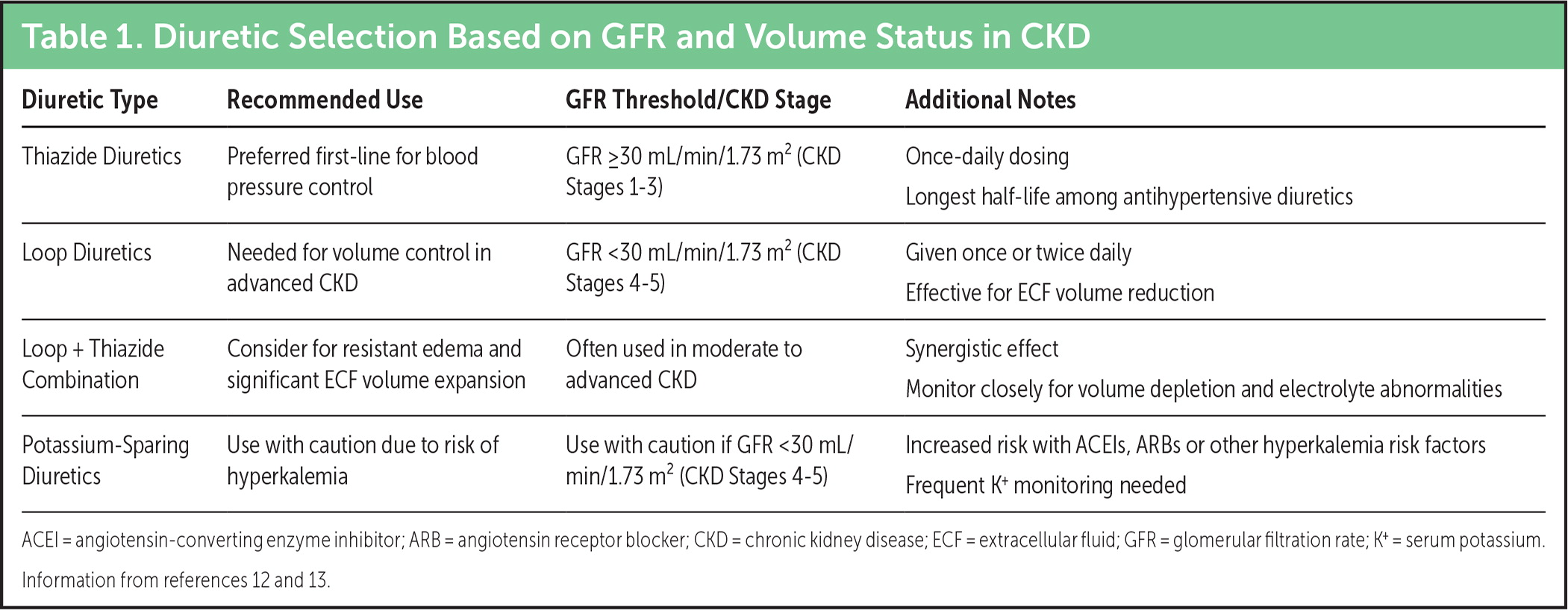

A diuretic can be prescribed initially in combination with an ACEI or ARB, or it can be added if a patient’s blood pressure remains elevated despite use of the maximum tolerated dose of a renin-angiotensin system agent. Clinical practice guidelines recommend that most patients with CKD be treated with a diuretic.12 These agents decrease extracellular fluid (ECF) volume, lower blood pressure, lower CVD risk, and increase the effectiveness of ACEIs, ARBs and other antihypertensive agents for patients with CKD.

The optimal diuretic for a patient will depend on their current GFR level and ECF volume status (Table 1).12 Thiazide diuretics have the longest half-life and are the best antihypertensive diuretics for people with normal to mildly reduced eGFR.12–14 Monitoring for volume depletion and electrolyte abnormalities is important, especially in older adults.

For patients with CKD who have persistently elevated blood pressure, physicians should select additional agents “based on CVD-specific indications to achieve therapeutic and preventive targets, and on avoidance of drug interactions or known side-effects.”12 These agents may include calcium channel blockers, select beta blockers and sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors.10–12 Although they may have less impact on glucose or blood pressure levels in patients with advanced CKD, these medications can still be beneficial to reduce the risk of CVD and heart failure and slow the progression of kidney disease.

Diuretic Selection Based on GFR and Volume Status in CKD

| Diuretic Type | Recommended Use | GFR Threshold/CKD Stage | Additional Notes |

| Thiazide Diuretics | Preferred first-line for blood pressure control | GFR ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (CKD Stages 1–3) | Once-daily dosing Longest half-life among antihypertensive diuretics |

| Loop Diuretics | Needed for volume control in advanced CKD | GFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (CKD Stages 4–5) | Given once or twice daily Effective for ECF volume reduction |

| Loop + Thiazide Combination | Consider for resistant edema and significant ECF volume expansion | Often used in moderate to advanced CKD | Synergistic effect Monitor closely for volume depletion and electrolyte abnormalities |

| Potassium-Sparing Diuretics | Use with caution due to risk of hyperkalemia | Use with caution if GFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (CKD Stages 4–5) | Increased risk with ACEIs, ARBs or other hyperkalemia risk factors Frequent K+ monitoring needed |

ACEI = angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB = angiotensin receptor blocker; CKD = chronic kidney disease; ECF = extracellular fluid; GFR = glomerular filtration rate; K+ = serum potassium. Information from references 12 and 13.

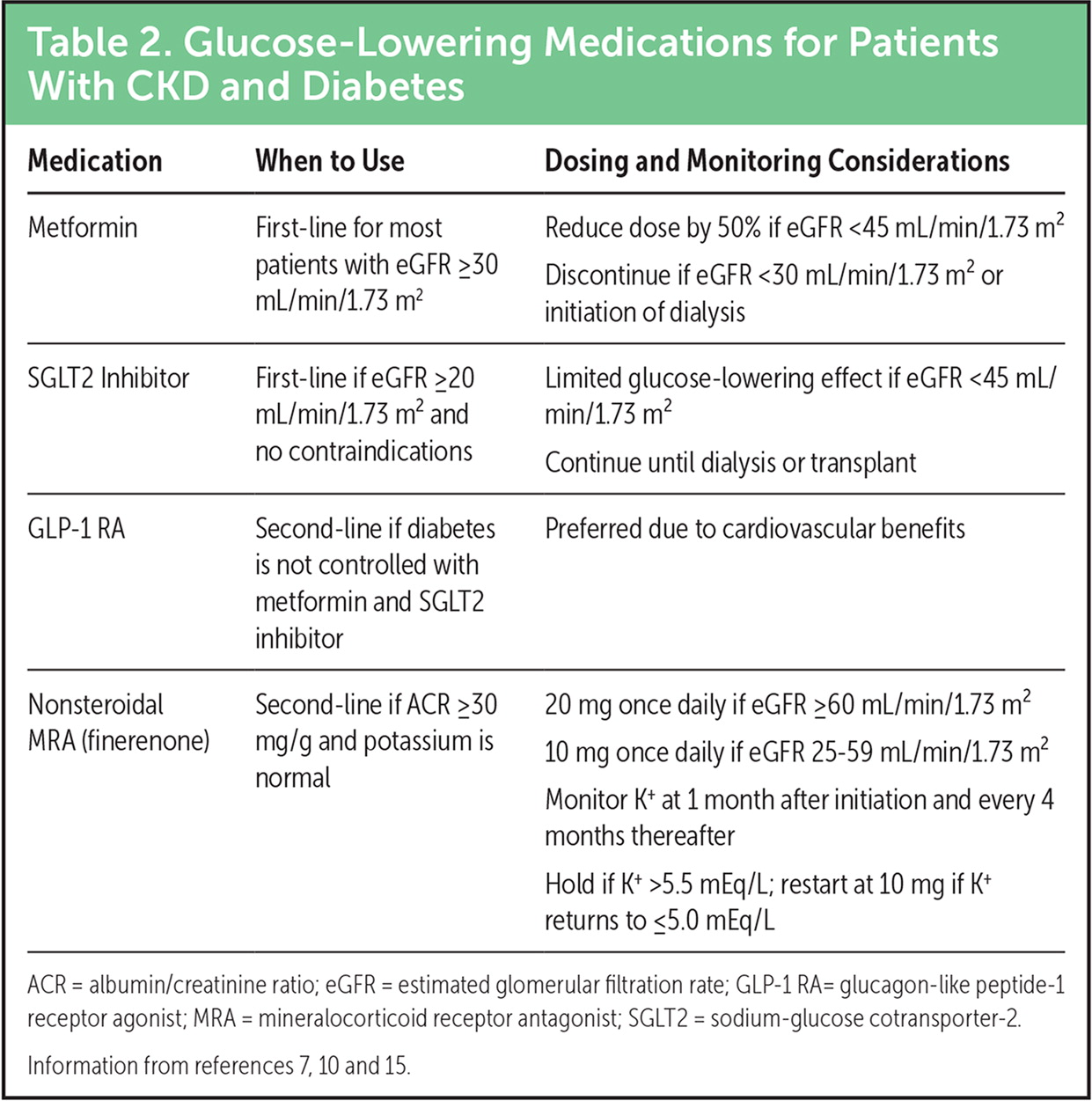

TREATMENT OF HYPERGLYCEMIA

Glucose lowering is another pillar of CKD management. Newer agents, such as SGLT2 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, have been shown to benefit patients with diabetes-related CKD beyond glucose lowering.11 These agents also appear to be beneficial when used in combination to treat comorbid CKD and diabetes. Table 2 summarizes recommended glucose-lowering medications and indications for use.

Glucose-Lowering Medications for Patients With CKD and Diabetes

| Medication | When to Use | Dosing and Monitoring Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Metformin | First-line for most patients with eGFR ≥30 mL/min/1.73 m2 | Reduce dose by 50% if eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73 m2 Discontinue if eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 or initiation of dialysis |

| SGLT2 Inhibitor | First-line if eGFR ≥20 mL/min/1.73 m2 and no contraindications | Limited glucose-lowering effect if eGFR <45 mL/min/1.73 m2 Continue until dialysis or transplant |

| GLP-1 RA | Second-line if diabetes is not controlled with metformin and SGLT2 inhibitor | Preferred due to cardiovascular benefits |

| Nonsteroidal MRA (finerenone) | Second-line if ACR ≥30 mg/g and potassium is normal | 20 mg once daily if eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73 m2 10 mg once daily if eGFR 25–59 mL/min/1.73 m2 Monitor K+ at 1 month after initiation and every 4 months thereafter Hold if K+ >5.5 mEq/L; restart at 10 mg if K+ returns to ≤5.0 mEq/L |

ACR = albumin/creatinine ratio; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; GLP-1 RA= glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist; MRA = mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist; SGLT2 = sodium-glucose cotransporter-2. Information from references 7, 10 and 15.

“Early collaboration between family physicians and nephrologists allows for an interdisciplinary approach to patient education, detection, and management of complications, and planning for the progression of renal disease.”16

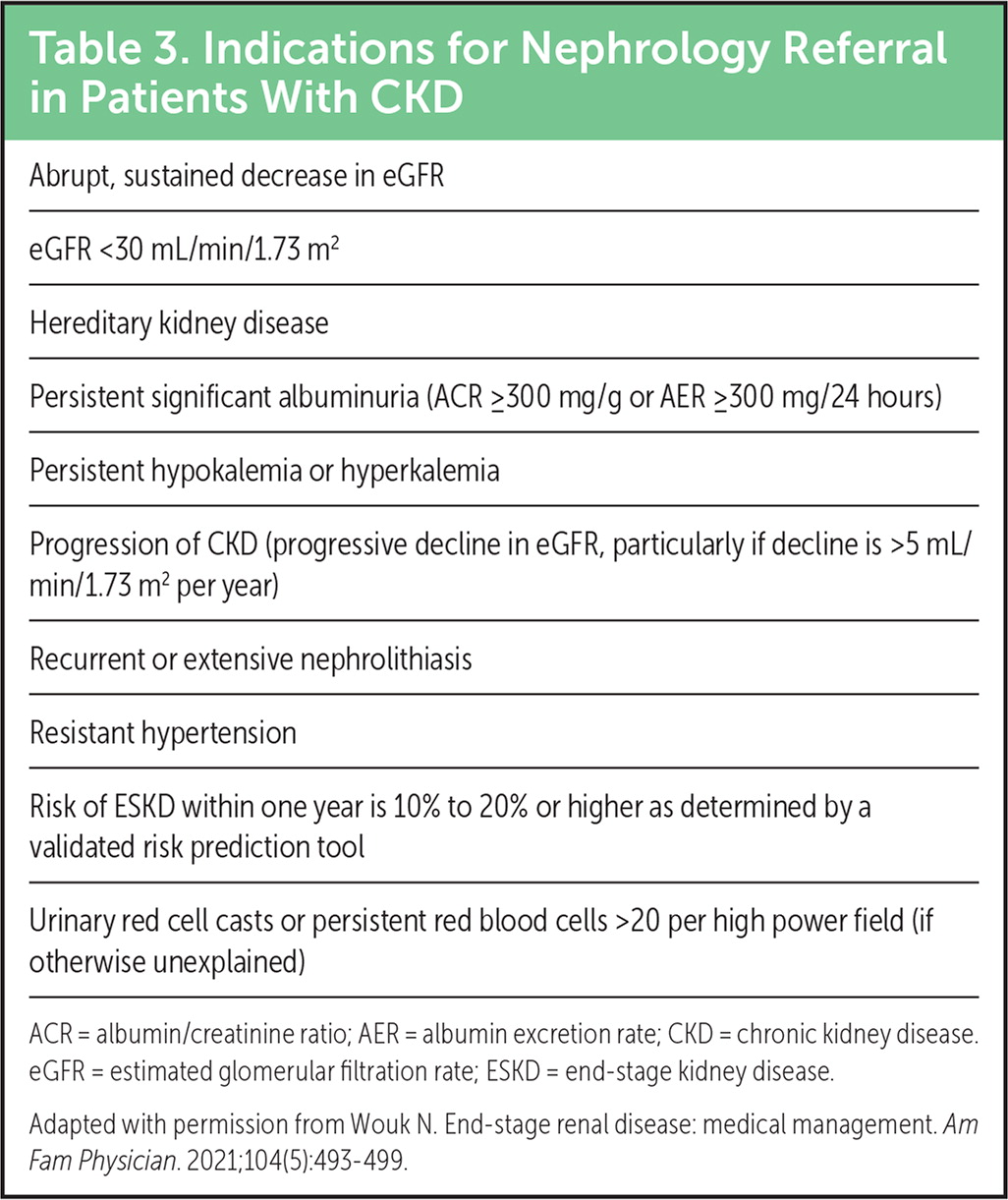

Referral to Nephrology

Although family physicians play an important role in preventing the progression of CKD to end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), research indicates that the total number of U.S. patients who have ESKD and need kidney replacement therapy is increasing and could surpass 1 million by 2030.17,18 Family physicians can enhance the quality of care by maintaining ongoing communication with their patients, optimizing medical and lifestyle interventions, and ensuring timely referral to nephrology. Guideline-recommended referral criteria are listed in Table 3.

Indications for Nephrology Referral in Patients With CKD

| Abrupt, sustained decrease in eGFR |

| eGFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 |

| Hereditary kidney disease |

| Persistent significant albuminuria (ACR ≥300 mg/g or AER ≥300 mg/24 hours) |

| Persistent hypokalemia or hyperkalemia |

| Progression of CKD (progressive decline in eGFR, particularly if decline is >5 mL/min/1.73 m2 per year) |

| Recurrent or extensive nephrolithiasis |

| Resistant hypertension |

| Risk of ESKD within one year is 10% to 20% or higher as determined by a validated risk prediction tool |

| Urinary red cell casts or persistent red blood cells >20 per high power field (if otherwise unexplained) |

ACR = albumin/creatinine ratio; AER = albumin excretion rate; CKD = chronic kidney disease. eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESKD = end-stage kidney disease. Adapted with permission from Wouk N. End-stage renal disease: medical management. Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(5):493–499.

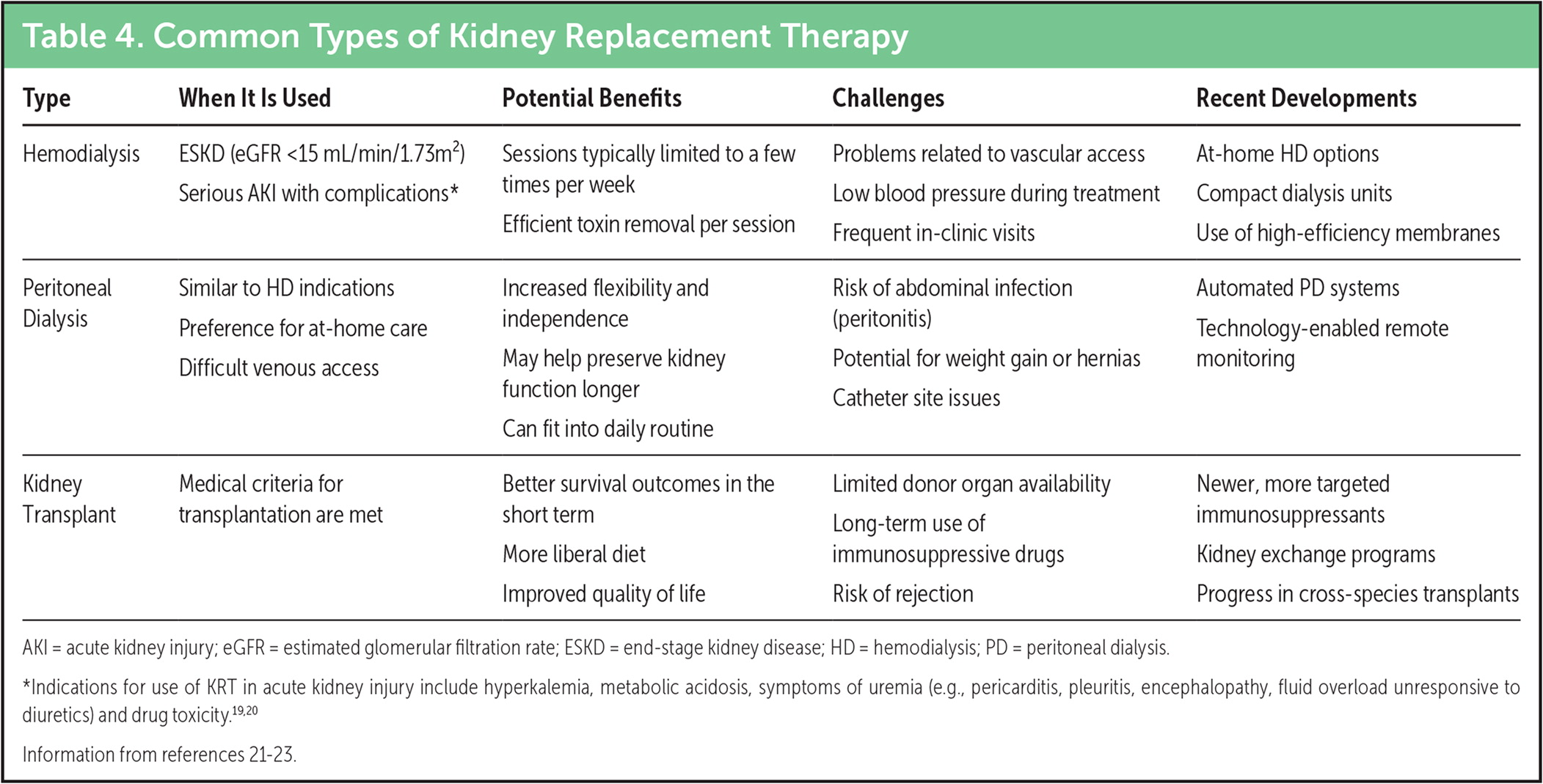

Kidney Replacement Therapy

Kidney replacement therapy is used when a patient’s kidneys no longer function adequately. Common types of KRT include hemodialysis (HD), peritoneal dialysis (PD) and kidney transplantation (Table 4). Historically, people with Stage 5 CKD (i.e., eGFR less than 15 mL per minute per 1.73 m2) — also known as ESKD — have been considered candidates for dialysis or a kidney transplant.

Family physicians can help educate and support patients with CKD and prepare them for the future by discussing KRT with them. The more patients know about the potential benefits and challenges of their KRT options, the better equipped they are to make informed treatment decisions with their health care team. Selecting the appropriate type of KRT requires a patient-centered approach that considers factors including comorbidities, predicted quality of life, social support and personal preferences.24 Shared decision-making and multidisciplinary collaboration are crucial to optimize outcomes for patients with CKD.

Common Types of Kidney Replacement Therapy

| Type | When It Is Used | Potential Benefits | Challenges | Recent Developments |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hemodialysis | ESKD (eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73m2) Serious AKI with complications* |

Sessions typically limited to a few times per week Efficient toxin removal per session |

Problems related to vascular access Low blood pressure during treatment Frequent in-clinic visits |

At-home HD options Compact dialysis units Use of high-efficiency membranes |

| Peritoneal Dialysis | Similar to HD indications Preference for at-home care Difficult venous access |

Increased flexibility and independence May help preserve kidney function longer Can fit into daily routine |

Risk of abdominal infection (peritonitis) Potential for weight gain or hernias Catheter site issues |

Automated PD systems Technology-enabled remote monitoring |

| Kidney Transplant | Medical criteria for transplantation are met | Better survival outcomes in the short term More liberal diet Improved quality of life |

Limited donor organ availability Long-term use of immunosuppressive drugs Risk of rejection |

Newer, more targeted immunosuppressants Kidney exchange programs Progress in cross-species transplants |

AKI = acute kidney injury; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; ESKD = end-stage kidney disease; HD = hemodialysis; PD = peritoneal dialysis. *Indications for use of KRT in acute kidney injury include hyperkalemia, metabolic acidosis, symptoms of uremia (e.g., pericarditis, pleuritis, encephalopathy, fluid overload unresponsive to diuretics) and drug toxicity.19,20 Information from references 21–23.

DIALYSIS

Dialysis filters the blood and eliminates waste from the body as a normal, healthy kidney would, although it cannot replace all of the kidney’s functions. Before a patient starts dialysis, non-renal conditions should be ruled out as potential causes of their symptoms. Initiation of dialysis is recommended for patients with CKD who have uremic symptoms that significantly impact daily living, uncontrollable fluid overload or an eGFR of approximately 5 to 7 mL per min per 1.73 m2 in the absence of symptoms.24 In the United States, approximately 82% of patients with incident ESKD begin HD, and approximately 14% begin PD.25

Conservative management, with or without palliative care, is an acceptable treatment option for patients who do not wish to proceed with KRT or are not likely to benefit from it.1 This approach involves managing advanced CKD complications (e.g., fluid overload, hypertension, anemia) and providing supportive symptom care to maximize the patient’s quality of life.26