Problematic policies that increasingly exclude family physicians from emergency departments are contributing to shortages in rural areas and, ironically, accelerating the use of NPs and PAs in these settings.

Fam Pract Manag. 2025;32(6):7-10

Author disclosures: no relevant financial affiliations.

Family physicians have historically played a significant role in delivering emergency care. However, over the last 50 years, policy changes have made it increasingly difficult for family physicians to practice in the emergency department (ED), even in rural areas with workforce shortages. As a result, non-physician clinicians are increasingly being used in these settings to help fill the void.1 Coherent emergency medicine workforce strategies that include family physicians are urgently needed to address these issues.

Our aim in this editorial is to describe what has led to this untenable situation and to offer some potential solutions.

A BRIEF HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

After World War II, changing demographics and social conditions as well as dwindling numbers of “general practitioners” led patients to increasingly rely on hospital “emergency rooms” (ERs) for unanticipated medical care. These early ERs were often staffed by junior medical and surgical house officers (i.e., interns or residents) who lacked the necessary clinical skills to manage the growing complexity of cases and had little to no attending supervision.

In the early 1960s, patients began demanding better quality emergency care. In response, hospitals introduced full-time emergency services. Many of these changes initially occurred in non-academic hospital settings, and general practitioners as community physicians were part of this effort. In academic medical centers, emergency medicine was largely controlled by other departments who used it as a training ground for their residents. They resisted emergency medicine becoming a specialty.2

In 1961, at a hospital in Alexandria, Va., James Mills, Jr., MD, a general practitioner, led a group of physicians who left their private practices to become the first full-time emergency physicians. Similarly, at Pontiac General Hospital in Michigan, 23 community physicians began staffing their emergency department (ED) around the clock. The Alexandria and Pontiac plans started the push toward the specialty of emergency medicine.

In 1968, the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) was formed, followed in 1976 by the American Board of Emergency Medicine (ABEM). In 1979, the American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) recognized emergency medicine as the 23rd medical specialty, although it was only given conjoint status at that time, meaning other specialties had representation on the board. Many family physicians championed the board specialty cause and were charter members of ACEP, and the founding executive director of the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) served on the ABEM board of directors for several years.

Eventually, in 1989, ABMS granted emergency medicine primary board status.3 Following this, ABEM closed its practice track, which had allowed physicians with 8,000 hours of emergency medicine experience to grandfather into the specialty. This included thousands of family medicine physicians. Henceforth, all candidates for the ABEM certification exam had to have emergency medicine residency training. Other board certification options have developed since that time (discussed in more detail below), but none are as widely recognized as ABEM because ABMS tends to dominate health care policy.

The concerted effort to exclude physicians who have trained in other specialties4 has led to workforce shortages and policies that allow or encourage the rise of non-physician clinicians in emergency medicine, particularly in rural and underserved areas, often without supervision.5 This is a deviation from the ideal that all patients in every ED should be seen by a physician.

MALDISTRIBUTION OF THE EMERGENCY MEDICINE WORKFORCE

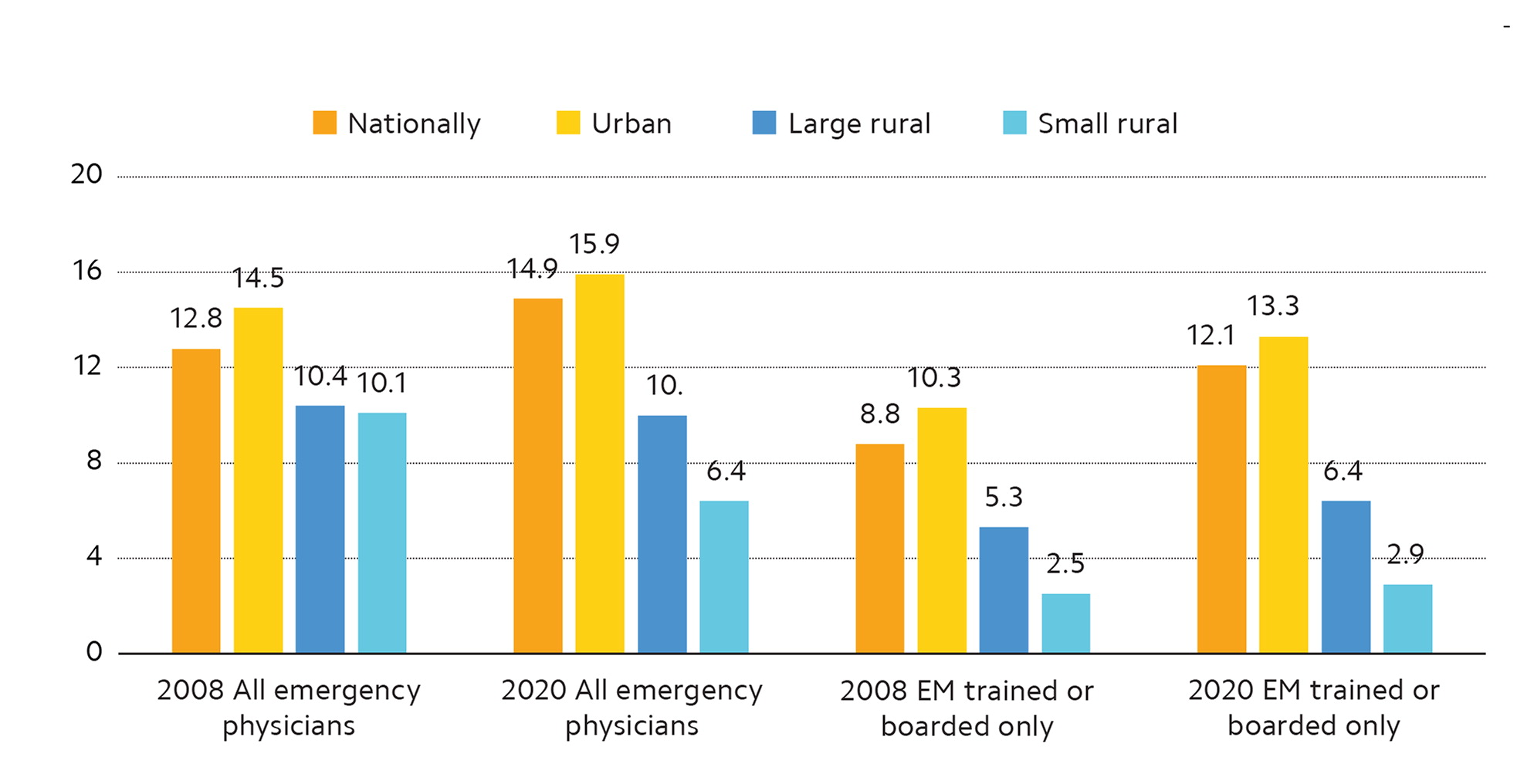

Recent projections of a surplus of physicians with emergency medicine residency training have created the false impression that an entirely emergency medicine residency trained workforce is possible to meet the need. For example, ACEP's 2021 workforce study by Marco et al predicted a surplus of nearly 8,000 emergency medicine residency trained physicians in the U.S. by 2030.6 But this scenario assumed 20% of emergency patients would be seen by a nurse practitioner (NP) or physician assistant (PA). It also likely overestimated the baseline number of active emergency medicine residency trained physicians (by including those who billed fewer than 11 emergency encounters annually) and underestimated the physician attrition rate, putting it at 3%. The ever-increasing workload and high levels of burnout among emergency physicians make it likely that attrition rates will be much higher, reducing the probability of a surplus of emergency physicians.

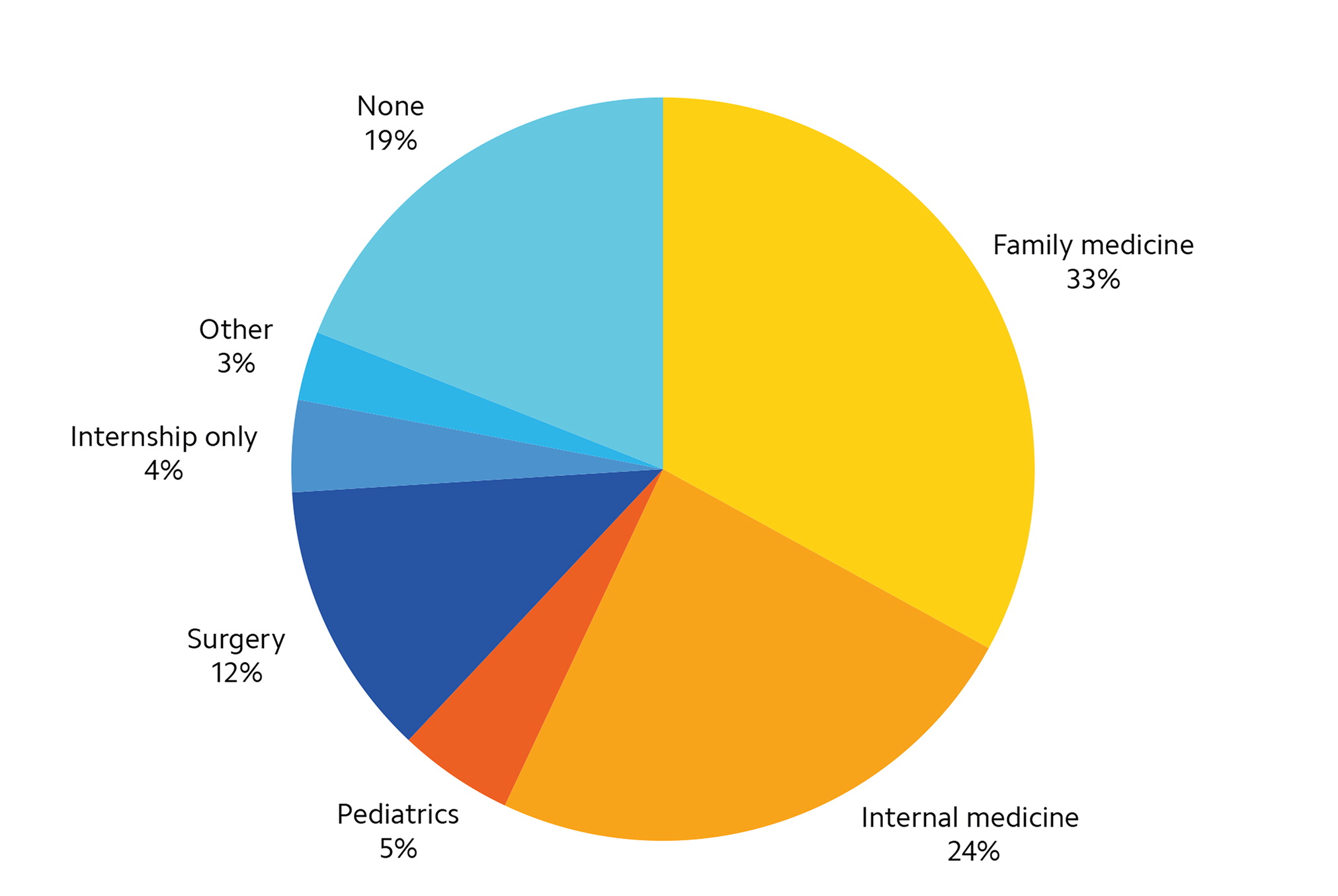

Instead, despite a growth in emergency medicine residency programs in the past decade, which has slightly improved the workforce, numerous recent studies5,7–8 have shown the existence of “emergency medicine deserts” (areas with very few residency trained emergency physicians), especially in rural parts of the U.S. These communities are home to 66.3 million residents, or 20% of the U.S. population, and they depend on family physicians for emergency care.5,8 Researchers estimate that primary care trained emergency physicians still make up approximately 20% of the rural emergency medicine workforce.9 Among emergency physicians who are not EM trained or ABMS EM board certified, family physicians represent the largest segment.5 (See Figure 1.) This suggests that family physicians are still playing a vital role in emergency medicine, despite ongoing resistance.10,11 With many rural hospitals closing (a record 19 closures in 2020 alone),12 family physicians will be critical to maintaining access to care.

POSSIBLE SOLUTIONS

The emergency medicine workforce faces a complex challenge, and solving it will require a multifaceted, collaborative approach. Solutions need to address the geographic disparity of residency trained emergency physicians and protect the quality of care in rural and underserved communities. We offer three suggestions:

Wider adoption of other board certification options. With ABEM closing the practice track, other certifying groups have arisen. The American Board of Physician Specialties (ABPS) offers a valid and reliable certification process — the Board of Certification in Emergency Medicine (BCEM). ABPS is recognized by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services,13 the U.S. Department of Labor,14 and the American Medical Association.15 Most state medical boards recognize the ABPS as well. (There are 71 allopathic and osteopathic state medical boards, and the vast majority do not differentiate between any of the three boards — ABMS, ABPS, or the American Osteopathic Association's Bureau of Osteopathic Specialists.) BCEM offers board certification for qualified physicians who have extensive experience working in emergency medicine or have completed emergency medicine fellowships. BCEM offers three pathways of eligibility to sit for the certifying exam,16 including completing a residency in emergency medicine, completing a primary care residency with 7,000 hours of emergency medicine experience, or completing an emergency medicine fellowship. Currently there are more than a dozen BCEM-approved graduate fellowships available in eight states.17 Many countries meet ED workforce needs through certification models that are like BCEM, where family physicians provide the majority of rural emergency care. For example, in Canada, family physicians can do an additional year of emergency medicine training and can become certified through the “CCFP-EM” pathway.18

Greater advocacy within family medicine. The AAFP has always supported family physicians in emergency medicine, but more can be done, particularly to address rural emergency medicine issues. Many family physicians face exclusionary hiring practices, even though they may be the ideal clinicians for rural EDs. While the AAFP provides excellent policy statements on the role of family physicians in emergency medicine, a more proactive approach is needed to make these policies a reality. Individual family physicians also need to become more engaged and work with their state chapters on these issues. For example, states such as Indiana and Virginia have adopted legislation requiring that physicians staff EDs.

Greater collaboration. In 2007, the Institute of Medicine (now National Academy of Medicine) called for a collaborative approach to rural ED staffing,19 but it has not taken place.20 Organized medicine must work together to address this issue. This could be accomplished through a task force comprised of rural health and hospital associations as well as professional societies and boards, and a joint statement could be developed, emphasizing the critical role of family physicians in rural emergency medicine.

The future quality of care in rural EDs depends on our collective and individual efforts to address these issues and shape critical policy regarding family medicine and emergency medicine.