A more recent article on Barrett esophagus is available.

Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(2):92-98

Related editorials: Should We Screen Patients for Barrett Esophagus? Yes: Men with Long-standing Reflux Symptoms Should Be Screened with Endoscopy and No: The Case Against Screening.

Patient information: A handout on this topic is available at https://familydoctor.org/familydoctor/en/diseases-conditions/barretts-esophagus.html.

Author disclosure: No relevant financial affiliations.

Barrett esophagus is a precancerous metaplasia of the esophagus that is more common in patients with chronic reflux symptoms, although it also occurs in patients without symptomatic reflux. Other risk factors include smoking, male sex, obesity, white race, hiatal hernia, and increasing age (particularly older than 50 years). Although Barrett esophagus is a risk factor for esophageal adenocarcinoma, its management and the need for screening or surveillance endoscopy are debatable. The annual incidence of progression to esophageal cancer is 0.12% to 0.33%; progression is more common in patients with high-grade dysplasia and long-segment Barrett esophagus. Screening endoscopy should be considered for patients with multiple risk factors, and those who have lesions with high-grade dysplasia should undergo endoscopic mucosal resection or other endoscopic procedures to remove the lesions. Although the cost-effectiveness is questionable, patients with nondysplastic Barrett esophagus can be followed with endoscopic surveillance. Low-grade dysplasia should be monitored or eradicated via endoscopy. Although there is no evidence that medical or surgical therapies to reduce acid reflux prevent neoplastic progression, proton pump inhibitors can be used to help control reflux symptoms.

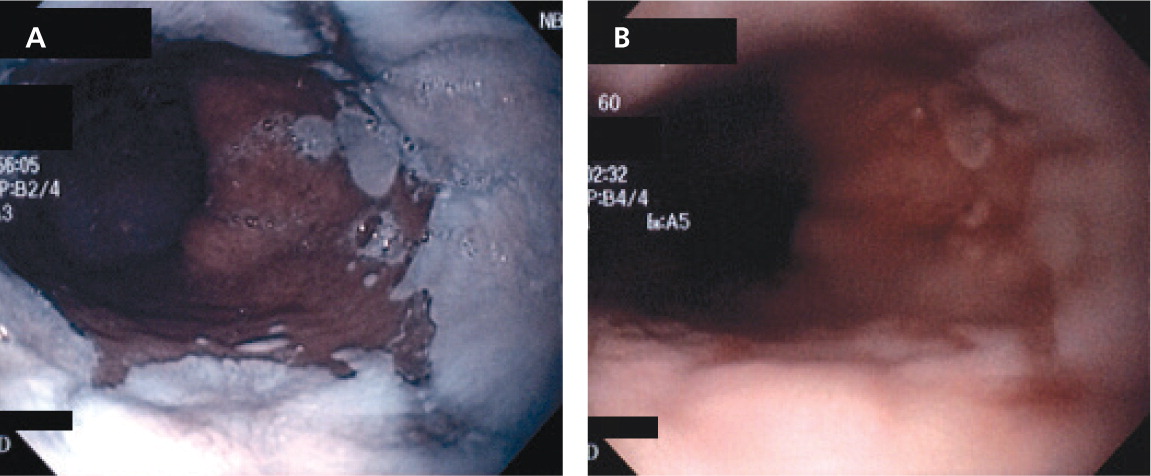

The hallmark of Barrett esophagus, which was first described by the British thoracic surgeon Norman Barrett in 1950,1 is metaplastic change of the distal esophagus from normal squamous cell epithelium to columnar epithelium2 (Figure 1). This metaplasia most often occurs in response to chronic exposure to acidic gastric fluid refluxing superiorly through the lower esophageal sphincter from the stomach.3 Barrett esophagus progresses to esophageal adenocarcinoma in a small percentage of patients each year.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | References |

|---|---|---|

| Screening endoscopy should be limited to patients with multiple risk factors for Barrett esophagus. | C | 18 |

| Although evidence from clinical trials is lacking, surveillance endoscopy is recommended for patients with nondysplastic or low-dysplastic Barrett esophagus. | C | 16 |

| Endoscopic eradication therapy (e.g., radiofrequency ablation, photodynamic therapy, endoscopic mucosal resection) is preferred over surveillance for patients with high-grade dysplastic Barrett esophagus. | C | 20 |

How Common Is Barrett Esophagus, and What Are the Risk Factors?

Estimates of the prevalence of Barrett esophagus in the general population vary from 1.2% to 1.6%.4,5 Although many patients with Barrett esophagus have a history of reflux, only a small percentage of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) develop Barrett esophagus. Risk factors include chronic reflux symptoms, smoking, white race, male sex, increasing age (particularly older than 50 years), hiatal hernia, and obesity.6–8 Patients with two or more factors are at significantly higher risk of developing Barrett esophagus.9

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

GERD is a common condition; more than 25 million Americans experience heartburn daily.10 A recent U.S. study showed that nearly 35% of all persons experience reflux symptoms at some time.11 A larger affected area (i.e., long-segment Barrett esophagus) is a risk factor for progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma.12

A meta-analysis of 26 studies found that the presence of reflux symptoms significantly increased the risk of long-segment Barrett esophagus (odds ratio [OR] = 4.9; 95% confidence interval [CI], 2.0 to 12) but not of short-segment Barrett esophagus (OR = 1.1).13 Data from several case-control studies suggest that cigarette smoking has a direct association with Barrett esophagus, with a 30– to 45–pack-year history resulting in an OR of 2.0 (95% CI, 1.2 to 3.3).14 Other risk factors include white race (compared with Hispanics or blacks), the presence of hiatal hernia, male sex, and obesity, with ORs of 2 to 4.6–8 Combinations of symptoms also increase risk. For example, obese adults with self-reported symptoms of acid reflux had an OR of 34.4 (95% CI, 6.3 to 188), greater than that in adults with reflux alone (OR = 9.3; 95% CI, 1.4 to 62.2). Patients reporting both acid reflux symptoms and smoking were also at increased risk of Barrett esophagus (OR = 51.4; 95% CI, 14.1 to 188).9

Many asymptomatic patients are also diagnosed with Barrett esophagus each year. In a Swedish study, 1,000 members of the general population were randomly selected to undergo upper endoscopy; the mean age of participants was 53 years, and one-half were women.4 The overall prevalence of Barrett esophagus was 1.6%, with a prevalence of 2.3% in patients with reflux symptoms and 1.2% in those without symptoms. In a more recent Italian study, 1.3% of patients had Barrett esophagus, and 46.2% of these patients were asymptomatic.5

What Is the Long-Term Prognosis Without Treatment?

Overall, patients with Barrett esophagus are at low absolute risk of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma (0.12% to 0.33% annual incidence). Longer segment length and high-grade dysplasia are associated with higher rates of progression to cancer.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A meta-analysis of 57 studies following 11,434 patients for a total of 58,547 patient-years found that the annual incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma was 0.33% in patients with nondysplastic Barrett esophagus (0.19% for patients with short-segment disease).15 A Danish cohort study followed more than 11,000 patients with Barrett esophagus for 5.2 years.16 About two-thirds of cancers were detected in the first year of follow-up, probably because of missed cancers or an error in biopsy sampling during the index endoscopy. After cases of esophageal adenocarcinoma discovered in the first year were excluded, the subsequent incidence rate was only 0.12% per year. The risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma was higher among those with low-grade dysplasia on the initial examination compared with those with no dysplasia (five cases per 1,000 patient-years vs. one). Compared with the general population, the relative risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma among patients with Barrett esophagus was 11.3.16

The likelihood of progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma is much higher in patients with high-grade dysplasia, with a progression rate of 42 per 1,000 person-years (extrapolated from reports of 4.2 per 100 person-years).17 Other risk factors include a longer esophageal segment involved (relative risk = 1.1 per cm beyond 2 cm), duration of symptoms longer than 10 years, the presence of dysplasia, and the presence of esophagitis.12

Who Should Be Screened?

Evidence-based guidelines recommend against routine screening for Barrett esophagus. Patients with GERD who have alarm signs should undergo endoscopy. Screening may be considered in patients with multiple risk factors for Barrett esophagus.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Although Barrett esophagus is associated with esophageal adenocarcinoma, no randomized trials have evaluated the effect of screening endoscopy on mortality rates.

In their most recent guidelines, the American College of Physicians (ACP), the American College of Gastroenterology (ACG), and the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) cited the high number of patients with GERD, the low incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma compared with other cancers, and the invasiveness and expense of endoscopy as reasons for not recommending routine screening (Table 1).18–21 A 2011 analysis estimated an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of $115,664 per quality-adjusted life-year saved compared with a strategy of no screening or surveillance.22 That study also found that the prevalence rate of esophageal adenocarcinoma would have to increase by 654% to generate an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of less than $50,000 per quality-adjusted life-year saved.

| Indications | American College of Gastroenterology18 | American College of Physicians19 | American Gastroenterological Association20 | American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GERD with alarm signs* or persistent symptoms despite proton pump inhibitor therapy | Endoscopy | Endoscopy | Endoscopy | Endoscopy |

| GERD with multiple risk factors | Use of endoscopy in high-risk patients should be individualized | Consider endoscopy | Screening endoscopy (weak recommendation, moderate-quality evidence) | Consider endoscopy |

| GERD without multiple risk factors | Endoscopy not recommended | Endoscopy not recommended | Endoscopy not recommended | Endoscopy not recommended |

| Dysplasia | None: twice in first year, then every three years | None: no more than every three to five years | None: three to five years | None: twice in first year, then every three years if no progression |

| Low-grade: six months, then annually until two consecutive negative tests | Dysplasia: more frequently | Low-grade: every six to 12 months | Low-grade: six and 12 months, then annually | |

| High-grade (if not eradicated): every three months | High-grade (if not eradicated): every three months | High-grade (if not eradicated): every three months |

The ACP/ACG/AGA guidelines recommend endoscopy for patients with GERD who have alarm signs (e.g., weight loss, anemia, evidence of bleeding or obstruction, dysphagia, symptoms that persist despite adequate proton pump inhibitor therapy). They also recommend that endoscopy be considered for patients with multiple risk factors for Barrett esophagus, especially those older than 50 years. None of the guidelines recommend routine endoscopy for patients with reflux symptoms alone.18–20,23 Patients who undergo screening endoscopy and have no evidence of Barrett esophagus do not require further screening or surveillance unless their symptoms change significantly.

Should Surveillance Endoscopy Be Performed?

Surveillance endoscopy is recommended every three to five years for patients with Barrett esophagus without dysplasia, every six to 12 months for those with low-grade dysplasia, and every three months for those with high-grade dysplasia (if not eradicated).

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

There have been no randomized trials of surveillance endoscopy for patients with Barrett esophagus. A recent cost-effectiveness analysis supports surveillance endoscopy with radiofrequency ablation every three months for patients with high-grade dysplasia, with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of €16,348 (approximately $22,000) per quality-adjusted life-year saved.24 Because of their relatively low progression to cancer, nondysplastic and low-grade dysplastic Barrett esophagus are typically managed with serial endoscopy and biopsies.

For patients without dysplasia or with low-grade dysplasia only, repeat endoscopy should be performed within one year because of the relatively high incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma resulting from missed cancer or inadequate sampling on the initial endoscopy.16,18,21 Thereafter, many guidelines recommend against annual surveillance endoscopy because the rate of neoplastic progression for nondysplastic Barrett esophagus is low (one case per 1,000 person-years16), and instead recommend repeat endoscopy every three to five years.19,20 Patients with low-grade dysplasia have a higher rate of neoplastic progression (5.1 cases per 1,000 person-years16), so they warrant slightly more frequent surveillance endoscopy. For these patients, the AGA and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommend serial endoscopy every six months for one year, followed by annual endoscopy (unless the level of dysplasia changes).20,21 High-grade dysplasia carries the highest risk of neoplastic progression (five-year risk exceeding 30%18), and most guidelines recommend serial endoscopy every three months if the patient cannot or will not undergo eradication treatment.18,20,21 A suggested management algorithm based on these recommendations is given in Figure 2.18,20

What Is the Best Treatment?

Because of their higher rate of progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma, lesions with high-grade dysplasia should generally be eradicated. Any mucosal irregularities such as ulcers or nodules found on examination should be resected endoscopically for diagnosis and staging. Endoscopic methods are now largely preferred over invasive esophagectomy.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Medical Therapy. Long-term acid suppression via proton pump inhibitors is used to control reflux symptoms. Although some retrospective cohort studies have shown that proton pump inhibitor therapy significantly reduces the development of dysplasia in patients with Barrett esophagus,25 it has not been shown to significantly delay or prevent progression to cancer.18

Surgery. In the past, esophagectomy was recommended for high-grade dysplastic Barrett esophagus, because it is the most effective way to remove lesions that are likely to progress to cancer.26 However, older patients and those with comorbidities may not be able to tolerate such an invasive procedure, and most are now treated endoscopically. Although previous studies suggested a role for fundoplication to reduce acid reflux,27 more recent, long-term studies have shown that this procedure does not significantly reduce the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma.18

Photodynamic therapy requires the administration of systemic photosensitizing agents, followed by endoscopic exposure of the abnormal tissues to laser light. A randomized, prospective control study involving 208 patients demonstrated that photodynamic therapy not only ablated high-grade dysplasia in 78% of patients, but also resulted in a 38% absolute reduction in the occurrence of adenocarcinoma compared with proton pump inhibitor therapy alone (P < .0001).29 Photodynamic therapy is the only treatment proven to significantly decrease the risk of cancer in patients with Barrett esophagus.18 However, it has significant adverse effects; patients must avoid exposure to sunlight to avoid cutaneous photosensitivity reactions, and 33% experience stricture formation.30

Endoscopic mucosal resection of lesions allows for diagnosis and treatment, and is recommended to determine the neoplastic T-stage in patients with evidence of mucosal irregularity. Complete response rates range from 76% to 100%, but the procedure is associated with significant complications, such as stricture formation (in up to 50% of patients), bleeding, and perforation.28,31

Recent studies have shown excellent results with the use of radiofrequency ablation. With this treatment, a 3-cm cylindrical balloon containing rings of electrodes is positioned against the lesion. Thermal energy is then delivered in a manner that preferentially ablates the Barrett mucosa.32 Radiofrequency ablation is especially effective in patients with dysplasia. A recent meta-analysis showed complete eradication of dysplastic mucosa in 91% of patients.28,33 It also has a much lower rate (7.6%) of stricture formation compared with endoscopic mucosal resection.34 Because radiofrequency ablation seems to have such a favorable clinical effect and complication profile, it is sometimes recommended even for patients with nondysplastic lesions.35 However, recent data suggest that it is not cost-effective for nondysplastic Barrett esophagus because of the lower risk of progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma.36

Endoscopic spray cryoablation with liquid nitrogen has been proposed as an alternative treatment for high-grade dysplastic Barrett esophagus. A recent small study showed that at two years of follow-up, 100% of treated patients had complete eradication of high-grade dysplasia, and 84% had complete eradication of metaplasia.37 However, because of limited data, it is not currently recommended as first-line therapy.20

Lifestyle and Diet Modifications. No evidence suggests that patients with Barrett esophagus benefit from the same lifestyle modifications recommended for patients with GERD. Alcohol use, which is a known cause of esophageal squamous-cell carcinoma, is associated with a reduced risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma when consumed in modest amounts (OR = 0.63; 95% CI, 0.41 to 0.99).38 Diets high in fruits and vegetables are inversely associated with the risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma, but adopting such a diet has not been shown to reduce the risk of developing this condition.39

Data Sources: Various PubMed searches were completed in Clinical Queries using the key terms Barrett's, esophagus, screening, surveillance, endoscopies, treatment, risk factors, surveillance, biomarkers, and adenocarcinoma. The search included meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials, clinical trials, and reviews. Also searched were the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality evidence reports, Essential Evidence Plus, the Cochrane database, DynaMed, and UpToDate. Search dates: January 3, 2012, to October 31, 2013.