Am Fam Physician. 2022;106(4):383-387

Related editorial: Emerging Roles for Family Physicians in Diagnosing and Treating Barrett Esophagus

Author disclosure: No relevant financial relationships.

Barrett esophagus is a premalignant change of the esophagus; however, malignant transformation to esophageal adenocarcinoma is rare in patients without dysplasia. Barrett esophagus is estimated to affect up to 5.6% of the U.S. population. Risk factors for Barrett esophagus include gastroesophageal reflux disease, obesity, age older than 50 years, male sex, tobacco use, and a family history of Barrett esophagus or esophageal adenocarcinoma. Patients who experience chronic gastroesophageal reflux symptoms plus additional risk factors should be considered for screening. Mucosal change consistent with Barrett esophagus is visualized during upper endoscopy; biopsy confirms the diagnosis and determines if dysplasia is present. Management of Barrett esophagus depends on the presence and severity of dysplasia; endoscopic treatment of dysplasia decreases the risk of malignant transformation. Surveillance after diagnosis is recommended to monitor for dysplasia and diagnose and treat esophageal adenocarcinoma at an earlier stage. Patients with Barrett esophagus should be offered proton pump inhibitor therapy to control reflux symptoms and possibly decrease the risk of developing esophageal adenocarcinoma. Statins, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and aspirin are associated with a decreased risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett esophagus; however, they should not generally be prescribed in the absence of another indication. Mortality benefits of screening and surveillance are uncertain.

Barrett esophagus is a premalignant change of the esophagus in which the normal squamous epithelium of the esophagus is replaced by metaplastic, columnar cells due to chronic reflux of acid and bile. This article reviews the best available patient-oriented evidence for the primary care of patients with Barrett esophagus.

| Clinical recommendation | Evidence rating | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Consider screening for Barrett esophagus in men with GERD symptoms and risk factors for Barrett esophagus, rather than those with GERD symptoms only. Consider screening women only if they have multiple risk factors.19,21,27 | C | Expert opinion and performance analyses of prediction tools on patients referred for endoscopy |

| Treat patients diagnosed with Barrett esophagus with a proton pump inhibitor daily; intensify to twice daily if needed to suppress symptoms of GERD.19,27,29 | B | Case-control and cohort studies and expert opinion |

| Do not routinely prescribe statins, aspirin, or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as anti-neoplastic therapy for Barrett esophagus unless a separate indication exists for their use.19,27,32 | C | Expert opinion in the absence of clinical trials |

| Recommendation | Sponsoring organization |

|---|---|

| For a patient diagnosed with Barrett esophagus who has undergone a second endoscopy that confirms the absence of dysplasia on biopsy, a follow-up surveillance examination should not be performed in less than three years. | American Gastroenterological Association |

Epidemiology

The estimated prevalence of Barrett esophagus, including asymptomatic patients, is up to 5.6% of the U.S. population, based on computer modeling.1

Esophageal adenocarcinoma is rare, accounting for 1% of all cancers diagnosed in the United States.2

The prevalence of Barrett esophagus is based on several risk factors3:

○ Low-risk, general population = 0.8%

○ Obesity = 1.9%

○ Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) = 3%

○ Age older than 50 years = 6.1%

○ Male sex = 6.8%

○ GERD plus any additional risk factor = 12%

○ Family history of Barrett esophagus or esophageal adenocarcinoma = 23%

Risk factors for Barrett esophagus are listed in Table 14–10; risks are more significant for patients with a longer duration of GERD and multiple risk factors.

Alcohol consumption does not increase the risk of Barrett esophagus or esophageal adenocarcinoma.11

One in 416 patients (0.24%) with Barrett esophagus may be diagnosed with esophageal adenocarcinoma per year12; however, a high-quality Danish study estimated a lower annual risk of one in 833 (0.12%).13

The risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma is higher in patients with Barrett esophagus with dysplasia12 (Table 213–16).

| Risk factor | Odds ratio for developing Barrett esophagus (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Onset of GERD before age 304 | 15.1 (7.9 to 28.8) |

| White Caucasian (self-identified)5 (relative to South Asian) | 6.03 (3.56 to 10.22) |

| Hiatal hernia6 | 3.94 (3.02 to 5.13) |

| GERD7 | 2.90 (1.86 to 4.54) |

| Male sex8 | 2.13 (1.87 to 2.46) |

| Central adiposity/obesity9 | 2.04 (1.44 to 2.90) |

| Tobacco use10 | 1.42 (1.15 to 1.76) |

| Age (per year)5 | 1.03 (1.02 to 1.03) |

Screening

There is no evidence from prospective studies that screening for Barrett esophagus in patients with GERD improves mortality or quality of life; therefore, Canadian and British guidelines recommend against universal screening for patients who have GERD.17,18

The American College of Gastroenterology acknowledges that evidence is insufficient, but based on expert consensus, suggests selective screening for Barrett esophagus in people with chronic or frequent GERD symptoms plus two additional risk factors, including age older than 50 years19 (Table 14–10).

Women are at significantly lower risk for esophageal adenocarcinoma compared with men; selective screening should be based on the presence of multiple risk factors.19

Life expectancy and comorbidities should be considered before a decision to screen.19 In a large veteran cohort study, 31% of patients who were newly diagnosed with Barrett esophagus had a life expectancy of less than five years and were unlikely to benefit from detection and treatment.20

Several tools to assess individual patient risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma are modestly more predictive than GERD alone, although optimal referral threshold for the number and magnitude of individual risk factors is unknown.21

The HUNT (https://sites.google.com/view/oacrisk) and Kunzmann tools rely on information typically collected during office visits and are available online and in a published nomogram.21–23

Screening for Barrett esophagus is done by sedated upper endoscopy.

Nonsedated transnasal endoscopy is a viable alternative but is not widely available.19

A swallowed capsule sponge device and breath testing have been studied for screening but are not validated and are not yet recommended as alternatives to upper endoscopy.19

Diagnostic Testing

The diagnosis of Barrett esophagus requires two conditions: (1) the normally pale-white esophageal mucosa appears abnormally salmon-colored on endoscopy, at least 1 cm above the gastric folds, and (2) biopsies of the abnormal-appearing esophagus must show columnar epithelium and the presence of goblet cells consistent with intestinal metaplasia.

The finding of no dysplasia, low-grade dysplasia, or high-grade dysplasia should be reported because this influences management and prognosis.

Complications affect between one in 200 and one in 10,000 upper endoscopies and may include cardiopulmonary events, perforation, bleeding, or adverse reactions to sedation.24

A diagnosis of Barrett esophagus causes anxiety, decreases quality of life, and increases life insurance costs.25

Surveillance

Screening and surveillance are of uncertain benefit to most patients.

Surveillance leads to detection of earlier-stage esophageal adenocarcinoma but does not lower all-cause mortality after adjusting for lead-time bias.26

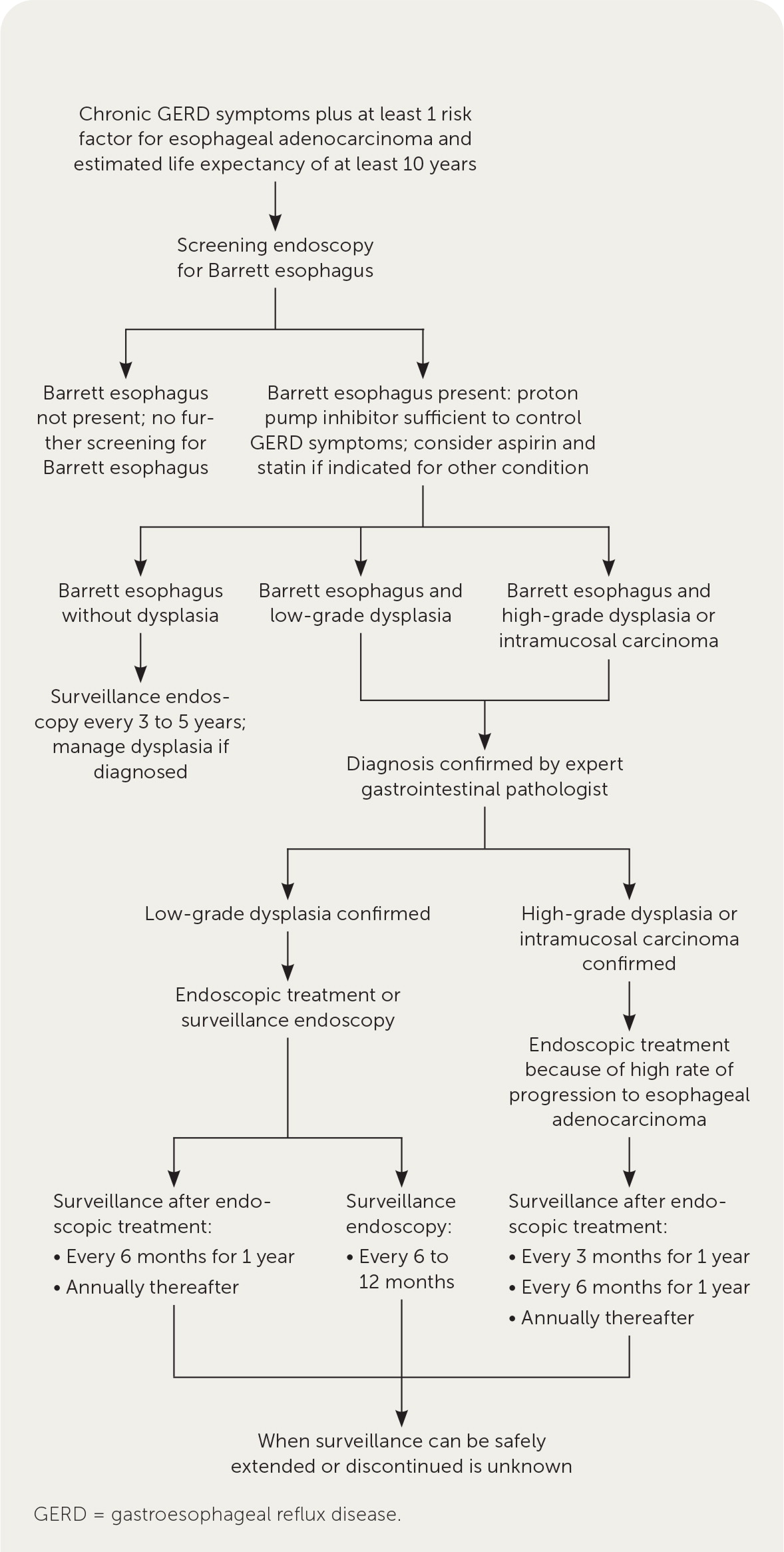

Figure 1 summarizes an approach to the screening, diagnosis, and management of Barrett esophagus, which is recommended by expert societies.19,27

There is no expert consensus on a safe age to discontinue surveillance, but cost-effectiveness modeling suggests stopping surveillance of nondysplastic Barrett esophagus for men and women without comorbidities after ages 81 and 75 years, respectively.28

Treatment

MEDICAL THERAPY

Proton pump inhibitor use was associated with a decreased risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett esophagus in North American studies (odds ratio [OR] = 0.47; 95% CI, 0.33 to 0.68) but not in Europe; additionally, a significant decrease was found in studies lasting less than five years, but not in studies of longer duration.29

In a randomized trial of 2,535 patients with Barrett esophagus, fewer patients who were treated with high-dose (40 mg) vs. low-dose (20 mg) esomeprazole (Nexium) developed a composite outcome of death, esophageal adenocarcinoma, or high-grade dysplasia; 10.9% vs. 13.7%, respectively (number needed to treat [NNT] = 37 over eight years).30

Once-daily proton pump inhibitor therapy is recommended, or twice daily if needed to control symptoms of reflux or esophagitis.19,27,29

In the same trial, aspirin (300 to 325 mg per day) reduced the same composite outcome vs. no aspirin; 11.2% vs. 13.4%, respectively (NNT = 46 over eight years), but only in patients who were not also taking a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug.30

Statins are associated with a reduced risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett esophagus (OR = 0.54; 95% CI, 0.46 to 0.63), although this was based only on retrospective observational studies.31

Although use of statins, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and aspirin is associated with a decreased risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma in patients with Barrett esophagus, these medications have harms that may outweigh their potential benefits and may also not be cost-effective for the treatment of all patients with Barrett esophagus without another indication.32

PROCEDURAL THERAPY

Endoscopic resection, radiofrequency ablation, and cryoablation can be used to remove or ablate discrete lesions or dysplasia of Barrett esophagus.

Endoscopic therapies for all patients with Barrett esophagus without dysplasia are cost-prohibitive and unnecessary.33

Endoscopic ablation for low-grade dysplasia reduces the absolute risk of progression to high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma by 10.9% (95% CI, 7.2% to 14.8%), with an NNT of 10 (95% CI, 7 to 14).34

Because of the low rate of progression to high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma, surveillance or endoscopic therapy for Barrett esophagus with low-grade dysplasia are reasonable options, based on expert opinion and cost-effectiveness modeling.19,33

Endoscopic radiofrequency ablation for high-grade dysplasia compared with a control group reduced the likelihood of esophageal cancer (2% vs. 19%; P = .04; NNT = 7) in one small, randomized trial and is cost-effective and safer than surgical therapy.33,34

Adverse effects of radiofrequency ablation include esophageal stricture (6%), bleeding (1%), and perforation (0.6%).35

Nodular lesions are removed by endoscopic resection for staging; T1a lesions (limited to mucosal invasion only) can be treated endoscopically, whereas T1b lesions (invading to submucosal level) require a multidisciplinary approach (oncology, gastrointestinal, thoracic surgery).36

Antireflux surgery is not better than medical therapy at preventing esophageal cancer (3.8 vs. 5.3 cases per 1,000 patient-years, respectively; P = .29).37

Prognosis

Investigators followed 4,207 patients with Barrett esophagus for 24,959 patient-years; of 921 deaths, 64 (7%) were due to fatal esophageal adenocarcinoma, whereas 857 (93%) were due to other causes.38

The mean life expectancy following a diagnosis of Barrett esophagus is 22 years; the lifetime risk of requiring intervention for high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma is between one in five and one in six patients.39

Patients with Barrett esophagus do not seem to be at an increased risk of all-cause mortality compared with the general population.40

This article updates previous articles on this topic by Zimmerman41 and Shalauta and Saad.42

Data Sources: A search of Essential Evidence Plus, the Cochrane database, recently published InfoPOEMs, and PubMed was conducted using the Clinical Queries database for the term Barrett esophagus. Search dates: November 2020, August 2021, December 2021, and April 2022.